Introduction

Micro, Small and Medium enterprises have played a critical role in India’s economic transition away from agriculture and allied activities towards growth in the non-farm sector. As stated in the report of the UK Sinha Committee1

“The Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs)… sector contributes in a significant way to the growth of the Indian economy with a vast network of about 63.38 million enterprises. The sector contributes about 45 per cent to manufacturing output, more than 40 per cent of exports, over 28 per cent of the GDP while creating employment for about 111 million people, which in terms of volume stands next to agricultural sector.”

An overwhelming majority of MSMEs are tiny and informal – 96 per cent of them were sole proprietorships – usually located within or just outside the owner’s household premises. Own-account enterprises (comprising 84 per cent of all enterprises) are those run by a single household member without paid workers and are often only one of multiple income sources for low-income households. The mean Gross Value Added of own account enterprises was Rs. 7,980 per month while the mean GVA of firms classified as establishments was Rs. 53,425 per month. Only 31 per cent are registered with any industry and trade association or development board, indicating the in- formal and unorganized nature of their operations.

About 20 per cent of the MSMEs are based out of rural areas, which indicate the deployment of significant rural workforce in the MSME sector and is a testimony to the importance of these enterprises in promoting sustainable and inclusive development as well as generating large-scale employment, especially in the rural areas. At the level of individual households, the expansion in non-farm employment opportunities is believed to have increased the average income of rural households and helped to mitigate the income risk of farm-based households through diversification.2

The Indian MSME sector, however, faces several constraints to growth. These include a lack of access to markets and value chains, the unmet demand for better infrastructure, difficulties in managing both skilled and unskilled workforce, technology or environmental constraints and finally, barriers to accessing regulatory facilitation.3

A critical factor limiting the performance potential of the MSMEs is access to finance. Credit gaps result from both demand and supply side factors. On the demand side, many MSMEs cannot access credit because of the financial documentation and collateral requirements for obtaining a loan; high interest rates; and long loan approval procedures, among others.

On the supply side, banks often consider MSMEs to be high-risk and high-cost clients to acquire, underwrite, and serve. Revenues per MSME client are lower than those of large f irms. Documented information on MSMEs is also often limited. These factors deter banks from lending to small MSMEs and focus their attention on bigger MSMEs or larger firms.

The Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana (PMMY) – features and overview

To enhance the flow of credit to Micro, Small and Medium enterprises (MSMEs), in April 2015, the Government launched the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana (PMMY) scheme for giving non-farm income-generating loans up to Rs10 lakh by existing government and private sector banks, and other financial institutions. PMMY offers unsecured loans for MSMEs requiring credit for investments in existing businesses, as well as for new start ups. Loans upto Rs. 50,000 are categorized as Shishu, from Rs. 50,000 upto Rs. 5 lakhs as Kishor and further up to Rs. 10 lakhs as Tarun loans. Further, by direction from the RBI since 2015, all lending to MSMEs lower than Rs. 10 lakhs by SCBs is required to be uncollateralized. The overall performance of PMMY in terms of number of loans as well as amount disbursed is given below. As can be seen, nearly 17.8 crore loans have been given, worth Rs 8.95 lakh crore in 2015-19. A vast majority, nearly seven out of eight loans were of the smallest Shishu category with average loan size of only Rs 27143, due to which additional income is limited and additional employment is negligible.

| Table 1: PPMY Loan for the period Apr 2015 to Mar 2019 | |||||

|

LoanType |

No. of Accounts |

No. of Accounts ( per cent of total) |

Disbursed Amount(Rs.Cr) |

Disbursed Amount

(percentof total) |

Average loansize (Rs) |

| Shishu | 154,012,989 | 86.48% | 418,042 | 46.72% | 27,143 |

| 15,40,12,989 | 4,18,042 | ||||

| Kishore | 19,212,879 | 10.79% | 281,970 | 31.51% | 1,46,761 |

| 1.92,12,879 | 2,81,970 | ||||

| Tarun | 4,857,528 | 2.73% | 194,765 | 21.77% | 4,00,954 |

| 48,57,528 | 1,94,764 | ||||

| Total | 178,083,396 | 100.00% | 894,777 | 100.00% | 50,245 |

| 17,80,83,396 | 8,94,776 | ||||

This can further be seen from the analysis of in terms of type of borrowers in the table below. It indicates that loans to new enterprises were less than one in twelve and women accounted for only one out of five borrowers. Thus, additional employment effects of PMMY loans are likely to very limited.

| Table 2: By various types of borrowers | |||||

|

Borrower Type |

No. of Accounts |

No. of Accounts (percent of total) | Disbursed Amount (Rs. Cr) | Disbursed Amount ( percentof total) | Average loansize (Rs) |

| Women | 37,062,562

3,70,62,562 |

20.81% | 1,29,153 | 14.43% | 34,847 |

| Minority | 6,251,640

62,51,640 |

3.51% | 29,029 | 3.24% | 46,435 |

| New Enterprises | 13,393,802

1,33,93,802 |

7.52% | 1,00,925 | 11.28% | 75,352 |

| PMJDYoverdrafta/cs (poor households) | 671,691 | 0.38% | 63 | 0.01% | 924 |

| Source:https://www.mudra.org.in/Home/ShowPDF Tab:OverallPerformance | |||||

Note:Computationforpercentdistributionofloansize,amountandaverageloansizebyauthors

Trends in MSME Lending over the years

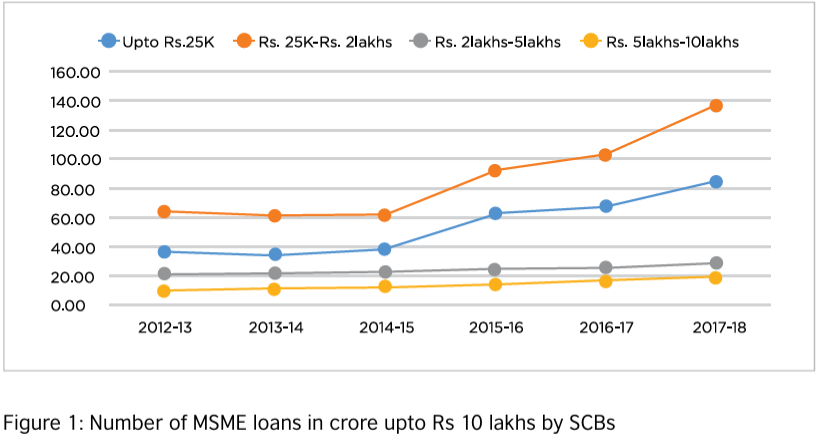

In this section, we look at the aggregate lending trends available from the RBI data to understand whether PMMY represents a substantial expansion of credit to MSMEs. The trend for number of loans definitely shows an upwards rise since 2015, particularly for the smallest two categories. This seems to indicate some additionality of PMMY.

But if we study the RBI data on the outstanding credit of SCBs, for loans lower than Rs 10 lakh and made to individuals or firms engaged in Industry, Trading, Transport or Professional Service occupations, the picture is different. This shows that compounded average credit growth was 7.9 per cent in the post-MUDRA 2016-18 three-year period as against 6.6 per cent pa in the pre-Mudra three-year 2013-15 period. That is a very marginal increase, and barely keeps up with inflation. Further it is only slightly above the growth rate of the overall net bank credit of 5.2 per cent in the period 2016-18.

| Table3: Small Loans (PMMY as well as others) given by Commercial Banks: RBI Data 4 | |||||

| Year ending 31st Mar | For loans of Rs 25,000 and Less | For loans above Rs 25,000 and up to Rs 2 Lakh | For loans above Rs 2 Lakh and up to Rs5 Lakh | For loans above Rs 5 Lakh and up to Rs 10 Lakh |

Total loan amount in Rs Crore |

| AmountoutstandinginRsCrore | |||||

| 2013 | 73,683 | 4,41,150 | 4,29,956 | 2,40,701 | 11,85,489 |

| 2014 | 37,166 | 4,89,525 | 4,75,832 | 2,82,642 | 12,85,166 |

| 2015 | 35,995 | 5,31,504 | 5,32,215 | 3,36,272 | 14,35,986 |

| 2013-15 | Pre-PMMY | 39,06,641 | |||

| 2016 | 45,884 | 5,74,849 | 5,79,623 | 3,98,791 | 15,99,146 |

| 2017 | 41,294 | 6,17,332 | 6,31,800 | 4,71,241 | 17,61,667 |

| 2018 | 43,984 | 6,86,322 | 6,98,796 | 5,78,719 | 20,078,21 |

| 2016-18 | Post-PMMY | 53,68,634 | |||

The Problems with PMMY Loans

Out of the 17.8 crore loans disbursed till March 2019, 36.3 lakh accounts were in default as on 31 March 2019, which was about two per cent of the loans disbursed under PMMY. This looks fairly healthy. But non-performing PMMY loans saw a jump of 126 per cent in just one year – the NPAs of loans issued under PMMY rose from Rs 7,277 crore in March 2018 to Rs 16,481 crore in March 2019.5 PMMY loans have raised concerns about becoming the potential source for the next bad loan crisis, along with some other schemes for MSMEs and farmers.

By their very nature, PMMY loans are flawed as financial products as these are structured as term loans with a tenor of three years, with periodic repayments of principal and interest, whereas 90 per cent or more of the amount is used for working capital, which is needed as long as the microenterprise runs. If the loan is repaid, the unit will not have working capital. These loans should have been offered as cash credit overdraft limits. That would also have reduced the interest burden on the borrowers.

To understand this better, let us take a typical Shishu loan, where the average loan size has been Rs 28,000. The microenterprise is likely to be in trading (such as a Kirana shop, or a street vendor), or in repairs (two-wheeler, mobile phones, consumer durables) or in services like tea-shops, ready-to-eat snack shops, tailors, barbers, cobblers, etc. Of the Rs 28,000 loan, the micro- entrepreneur will normally invest a large part, at least Rs 20,000 in working capital to buy supplies of raw material or goods to be sold, paying wages and paying for rent and electricity. Investment in fixed assets, if any, may go into wooden shelves and weighing scale for a Kirana shop; a gas cylinder, cook stove and utensils in case of a tea and snacks shop; and basic equipment and tools in case of a repair shop.

Now, with a PMMY loan, this micro enterprise has to make a periodic (monthly or quarterly) payment of a principal instalment and interest. For a loan of Rs 28,000 repayable monthly over 36 months, that could be as much as Rs 1000 per month. As we know, a vast majority of loans go into trading activities, and if we assume that the sales turnover was four times of the loan amount, it would be Rs 1.12 lakh. Even if assume 15 per cent margin, on the higher side, the gross income will be Rs 16,800 in the year. The net income from the microenterprise is unlikely to be more than Rs 1400 per month, which means the monthly instalment is 70 per cent of the incremental income, leaving behind a mere Rs 400 per month.

This is bound to be drawn out by the micro-entrepreneur to meet household needs. If in some months due to contingencies such as illness in the family, if the micro-entrepreneur draws out more money, she will end up skipping an instalment. As happens in many cases, there is an adverse event like illness in the family, or a theft in the shop, or a client does not repay goods/services rendered on credit, there is no cushion to maintain the instalment repayment and this leads to the loan becoming a non-performing asset. Catching up on older instalments becomes tougher.

Even if assume that the micro-entrepreneur has other cashflow to meet their personal needs, they will still be able to save only about Rs 400 per month, which in 36 months will add up to Rs 14,400, and is just about half of the loan taken. In the meanwhile, three years have passed and if anything, the working capital requirement would only have increased beyond Rs 28,000. Thus micro-analysis shows why PMMY loans will not work to improve things for most of the micro-entrepreneurs, except temporary relief for the f irst one or two years.

The Way Forward

Yet, we cannot afford to merely critique the PMMY scheme. A viable alternative is needed. The inevitable conclusion from the above analysis is that PMMY needs to be revamped.

As explained earlier, PMMY loans are prone to default because debt for new enterprises is the wrong financial product. In debt financing, the entrepreneur has to maintain the f ixed instalment repayment and this leads to the loan becoming an NPA. Catching up on older instalments becomes tougher. Had the Mudra financing been done using the micro equity framework, the build-up of NPAs would have been avoided. Currently this is tried to be obviated through credit guarantees from the Credit Guarantee Trust for MSMEs (CGT-MSME).

But no guarantee mechanism can sustainably deal with failure rates as high as a 70-80 per cent among new enterprises. Only a micro-equity fund mechanism can handle this. While many enterprises would go under, or would be marginally profitable, returns from the surviving and thriving enterprises would have been enough to offset the investment losses. If necessary, till the instrument gets fully established, a risk cushion may be provided by an entity like the CGT-MSME to the early small investors in micro-equity funds, so that they are assured of at least principal protection. Perhaps the MUDRA Agency can be redesigned and given this role.

An expert committee was established by the Reserve Bank of India early this year under the Chairmanship Shri U.K. Sinha. The RBI announcement said:6

“Considering the importance of the MSMEs in the Indian economy, it is essential to understand the structural bottlenecks and factors affecting the performance of the MSMEs. It has, therefore, been considered necessary that a comprehensive review is undertaken to identify causes and propose long term solutions, for the economic and f inancial sustainability of the MSME sector.”

The expert committee was established soon after the RBI allowed a one- time restructuring of existing debt up to Rs 25 crore for the micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) which have defaulted on payment but the loans given to them have continued to be classified as standard assets. This includes all the PMMY loans. The report of the Committee came out in Jun 2019 and it made several recommendations on financing, which are excerpted below:

- Ministry of MSME may consider setting up of a Non-Profit Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) to support crowd sourcing of investments by various agencies particularly to pave the way for conducive business ecosystem for MSMEs…

- The Committee has made wide ranging recommendations for expanding the role of SIDBI. The Government should deploy the PSL shortfall to SIDBI on the lines of RIDF fund of NABARD, for lending to State Governments as soft loans for infrastructural and cluster development. SIDBI should deepen credit markets for MSMEs in underserved districts and regions by handholding private lenders such as Non-Banking Finance Companies (NBFCs) and Micro Finance Institutions (MFIs). Further, they must develop additional instruments for debt and equity which would help crystallise new sources of funding for MSMEs and MSME lenders such as first loss guarantees, Pass Through Certificates (PTCs), etc. SIDBI should gradually take on the role of a market maker for SME debt on select platforms.

- SIDBI, as a nodal agency, should ideally play the role of a facilitator to create platforms wherein various Venture Capital Funds can participate and in turn create multiplier effect for providing equity support to MSMEs. A Government sponsored Fund of Funds (FoF) to support VC/PE firms investing in the MSME sector should be set up to encourage them to invest in the MSME segment…

- The Committee recommends for the creation of a Distressed Asset Fund, with a corpus of `5000 crore, structured to assist units in clusters where a change in the external environment… has led to a large number of MSMEs becoming NPA…

- With the increased availability of data from several sources, including GSTN, Income Tax, Credit Bureaus, Fraud Registry, etc., it is now possible to do most of the due diligence online and appraise the MSME loan proposals expeditiously. It is recommended that banks should have access to such surrogate data for speedier and robust credit underwriting standards.

While it will require several years to implement the recommendations of the UK Sinha Committee, here are some recommendations about changes in the design of existing loan products which can be implemented in the short run.

- Below Rs 1.25 lakh (the new RBI limit for microfinance loans), we may continue the present MFI system of giving a composite loan with an equated monthly instalment, following the maxim “don’t fix what ain’t broke”. We can go more digital as suggested in recommendation 18 of the UK Sinha Committee report to undertake due diligence, help build borrower cashflow history, to look for winners who can graduate.

- From Rs 1,25 lakh to Rs 5 lakh, we may continue with loans, but make those into two parts, first a term loan (which NBFCs or banks/SFBs could give) and a second component can be added – a Cash Credit limit which should be given by a co f inancing SFB/RRB/UCB/ any other commercial bank. All cashflows must be routed through the cash credit account to keep good track of the business.

- From Rs 5 lakh upwards, we should offer micro-equity for start-ups which are GST registered and are willing to share their input/output data to ensure digital tracking of business input purchases and output sales, plus utility bills, statutory payments etc. The return on the micro-equity can be linked to the revenue share (which can slowly decline as a per cent and eventually taper off once the hurdle IRR of 60-70 per cent pa is achieved. So, there will be no need to monitor profits, which are hard to determine.

Micro-Equity financing is based on the principle that in case of a start-up enterprise, the f inancier must share the risk if he wants to share the profits. The proportion of risk and return sharing can be negotiated in advance but unlike in a debt instrument, there is no promise of a fixed return to the financier nor are the dates and amount of repayment (interest and principal) instalments pre-fixed. The product should ideally be offered by entities registered with SEBI as Alternative Investment Funds, AIF Category I, with some tweaking on extant provisions. Those details can be worked out by a technical working group.

In the meanwhile, the RBI can guide MFI-NBFCs, NBFCs, SFBs and commercial banks to offer the first two types of loan products. The task is urgent. Millions of MSMEs are waiting for this to happen and if it happens, it will generate a large number of employment.

Endnotes

- Expert Committee on Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Chair Mr UK Sinha, Reserve Bank of India, 2019https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationReportDetails.aspx?UrlPage=&ID=924 2 Morduch 1995

- Planning Commission 2013

- Basic Statistical Returns for Scheduled Commercial banks, RBI for last 6 years

- Business Today June 25,2019

- RBI policy Statement December 5, 2018