A Triad of Crises Caused by the Present Economic System

Humanity is facing three crises – social, economic and ecological. These are characterised by increasing levels of breakdown of the social contract, growing economic inequality and poverty amid plenty, and a fast deteriorating environment, to the point where several species have been rendered extinct. Yet the knowledge systems we have used so far to address such challenges, from a belief in the scientific method to accepting the utility maximising axiom of economics, seem no longer adequate to explain what is happening. Likewise, institutions we had put faith in, all the way from the neighbourhood residents’ welfare association to the United Nations Security Council, seem unable to deliver results. What could be the cause of this breakdown and what can be the way forward?

This paper asserts that the fundamental cause of all these crises is the present economic system. The system is designed to maximise return on financial capital invested in any economic transaction. Since most of financial capital is owned by rich individuals and private corporations, the deployment of capital for maximising return for them does not automatically translate into maximising welfare for all. Adam Smith had posited the “invisible hand” which implied that economic actors basing decisions on self-interest create a positive outcome for the economy in terms of enhancing everyone’s utility. But this does not work in a situation where financial resources are concentrated in a few hands. Instead it promotes triple exploitation – of human beings, of social cohesion and of natural resources. This is economically inefficient as it generates less than the optimal total utility that is possible. In addition, this situation is not just unsustainable, but also is unconscionable.

Capital as the basis for economic progress as well the cause of problems

We begin this paper with restating some fundamental propositions. First, the source of all wealth and well-being is in nature. However, for the natural resources to become wealth, or generate well-being, human labour and skill has to be applied. This is what Karl Marx called the labour theory of value. Further, human labour and skill needs to be applied in an organised manner and that requires knowledge, which comes out of accumulated experience, gathered, processed and passed on over many generations. For this to happen systematically, we need societal institutions – for learning, documentation, norms of quality and standards, safe and efficient work practices and so on. This is social capital. All this is not possible without some amount of buildings, equipment, and other physical capital. And to acquire those, we need finance. Thus there are five types of capital namely – natural, human, social, physical and financial capital.

The inter-relationship between these five types of capital broadly works as follows: human capital, organised using social capital, acts on natural capital to produce physical capital and generate surpluses in the form of financial capital.

The problem is that in the quest for maximum return on financial capital, more surplus is extracted out of human, social and natural capital than is sustainable and this leads to all kinds of difficulties in the economy. Yet, financial capital is necessary to be invested to unleash a virtuous cycle of growth and progress. Thus control over financial capital and its deployment for maximising social welfare, while paying attention to the most vulnerable members of society, and ensuring the environment is conserved, has becomes the key challenge of our times, for the world and for India. In this paper, we focus on the problems facing India.

How the present economic system creates poverty and unemployment

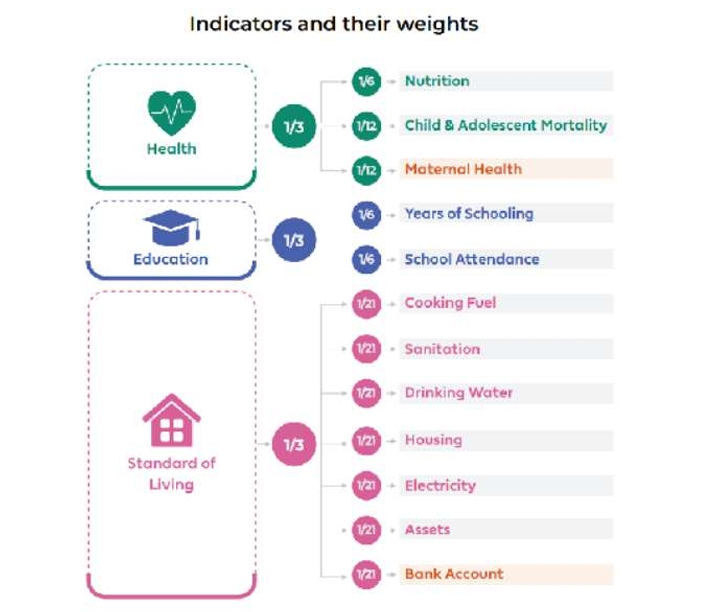

India has seen unprecedented growth since the beginning of the 21st century. India’s net national income increased Rs 39.3 lakh crore in 2000-01 to Rs 133.5 lakh crore in 2022-23 (both at 2011-12 prices). The GDP in 2022-23 was Rs 160 lakh crore. The per capita income in 2000-01 was Rs 38515 and by 2022-23 it went up to Rs 96522 (both at 2011-12 prices). [1]Despite the net national income going up by over three and half times, the per capita income went up by only two and half times, showing the rise in inequality. Perhaps relative inequality would have been acceptable but for the fact that at the lower end of the per capita income curve, the levels are well below acceptable human standards of living. India changed the way it used to measure poverty, from the earlier one based on household level surveys of monthly per capita expenditure to one based on multiple indicators comprising health, education and standard of living. (See diagram on next page).

The National Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) report 2023[2] covering the period 2019-21 showed that while there was a lot of progress on reduction in poverty in India, we still have the largest number of poor people worldwide at 22.8 crore persons, followed by Nigeria at 9.6 crore. The rural headcount poverty ratio was 19.3 %, about four times the urban poverty headcount. This refers to proportion of households who suffer from multiple deprivations among the 12 indicators. The intensity of rural poverty was 44.6% and urban not much lower at 43.1%. Intensity refers to average proportion of deprivation for the 12 indicators among those who are multi-dimensionally poor. If we want to dig deeper into the effects of poverty, let us look at the Government of India’s National Family Health Survey 5th Round (2019-21)[3]. As per this, 36% of children under age five years were stunted; 19% were wasted; 32% were underweight; while 3% were overweight. Children born to mothers with no schooling and children in the lowest wealth quintile were most likely to be undernourished. Two-thirds of the poor households had at least one person is deprived of adequate nutrition.

The effect of poverty is that a large number of human beings – our fellow citizens – do not get the opportunity to develop to their full potential. It deprives the nation of human capital. This is a direct consequence of the present economic system, which simultaneously produces a few super rich persons , the richest two being Mr Mukesh Ambani and Mr Gautam Adani who together had reported wealth of over Rs 11 lakh crore [4], while condemning crores to a sub-human existence.

One of the ways to overcome poverty is to help them find work and earn a living. As per the ILO’s India Wage Report, 2018, [5]of the total 40.1 crore persons employed in India in 2011–12, more than half (51.4%, or 20.6 crore people) were self-employed, and of the 19.5 crores wage earners, 62% (i.e. 12.1 crore) were employed as casual workers. Employment in the organized sector has scarcely grown since then, but even in this sector many jobs have been casual or informal. The opportunities for work are at such low wage rates that it is not possible for many workers to earn a living wage. Due to low wages, the proportion people of working age who are “seeking or available for work”, also known as the labour force participation rate (LFPR), has remained low compared to other comparable economies.

Despite lower LFPR, unemployment (ratio of those not finding work to the total labour force) is so high among the youth that one in four is unemployed, and the ratio goes up to one in three for educated young men and one in two for educated young women. This is on top of the fact that due to domestic, social and reproductive responsibilities; in the first place less than one in three women are able to participate in the labour force. Even this is an exaggeration as the GoI treats unpaid women working in household enterprises as “employed”. If those are excluded the Female LFPR for India is below 10%.

For people living in rural areas, agriculture, the main source of work and income, has become non-remunerative to the point where thousands of farmers are committing suicide every year. This is a direct consequence of pushing agriculture into the market economy. While the high-input intensive, high-yielding agriculture was introduced in the late 1960s to overcome food grain shortages, and it did so successfully, since then Indian farmers have been made increasingly dependent on purchased seed, fertiliser, pesticides, diesel, electricity, pumps and pipelines for irrigation, tractors for ploughing, and lately even combines for harvesting.

In turn, farmers have to produce those cereal crops which have a minimum support price, which was mainly paddy and wheat or cash crops like cotton, sugarcane and soybean. This has propelled Indian agriculture into a situation where it is unsustainable without large subsidies on input as well as output side (through MSP). In the mean while due to over-drawing of ground water, intensive chemical fertiliser use and reckless use of pesticides, this market-oriented Indian agriculture is a major contributor to environmental degeneration,

The urban informal sector is thus the last refuge for landless and marginal farmers seeking work away from the village. In cities, they work as manual labourers in construction, transport, retail trade, security and myriad urban menial services. The working conditions and remuneration levels remain very poor. Thus millions earn below a living wage, and live sub-human lives, because the current economic system does not generate enough rural jobs. The impact of this on individual lives as well as on village communities is terrible.

How the present economic system erodes social capital

India was famous for its social capital in the form of the village economy with its jajmani system. Everyone – land owners, farmers, agricultural workers and artisans – had a role and everyone was taken care of in terms of livelihoods. The landlords collected rents but also spent on maintenance of village ponds, irrigation channels, local grazing land and village forests, in addition to temples and chaupals. The cultivators paid the artisans in terms of food grains, and so on. This system slowly got eroded and after the British colonised India and used the divided and rule policy, the traditional Indian social capital got seriously eroded. Many social movements were started to rebuild the social capital – the Arya Samaj, the Prarthana Samaj, the Brahmo Samaj, respectively in Punjab, Maharashtra and Bengal. These were intra-community and not bridging forms of social capital. The freedom movement helped build a new form of social capital where caste and community took a back seat and commitment to the independence cause came in the forefront.

After Independence, the social capital built organically during the freedom movement was substituted by top down attempts at building new forms of social institutions – the gram panchayats, the village cooperatives, trade unions and political parties. Some of these took root and others did not, but most got overlaid by earlier caste and religious considerations. The decline of traditional social capital was not compensated by modern forms of social capital, because the market economy did not invest in building social capital. Instead they found other ways to get to their goal of maximising return on financial investments, from bribery to crony capitalism.

Many scholars such as Prof Stephen Marglin of Harvard University have shown that the economic system has devalued the sense of community and destroyed social capital as human relations are replaced with market transactions aimed at maximising profits.

Two fields where the market economy has wreaked havoc are education and health. As education has increasingly become privatised, from schooling to universities, the purpose seems to have shifted from developing the potential, knowledge and capability of students to maximising return on investment for the “owners”. We say “owners” in quotes, since by law all educational institutions are non-profit entities, so the founders can at best be Trustees and cannot withdraw any surpluses. Yet, thousands of crores are made by people in the education business, through the stratagem of private companies providing related and supporting services like running hostels, student mess facilities, bus services and selling uniforms and text books. This profit making mentality erodes social capital to such an extent that in universities, students see themselves as consumers of education, holding their faculty responsible for delivering education which will enhance the students’ value in the job market. Thus job placement at high salary levels becomes the measurable index of a university’s performance.

Another way in which the current economic system has destroyed social capital is by reducing relationships to transactions. Earlier, village haats or town bazaars used to be characterised by intense human interaction. There, words like bargain, trust and shame, and phrases like ‘let’s meet half-way”, “pay me later”, “face-saving” and “word of honour” were used. These were the building blocks of wider social collaboration. The same people got together when they wanted to build a mosque or a school or establish a panjrapole (animal shelter) for stray cattle. Slowly norms and institutions developed out of a dialogue and participative process.

In contrast, in the high-end market economy, enabling transactions without interactions, has led to strongly devaluing social capital. The extreme example of this is algorithmic screen based trading where computers could perform all the functions from end to end to complete millions of dollars of transactions in a few seconds, without any human from the two transacting parties ever talking to each other. In faceless transaction markets, these are replaced with bulky contracts backed by elaborate laws and expensive enforcement mechanisms.

Society has been devising methods to address various problems of life, one of which is risk – to lives, health, crops, livestock, assets and businesses, etc. The original societal solution for dealing with adversity was mutual help. This slowly evolved into mutual insurance societies. Insurance thrived as mutual for over two centuries. It was only when some mutual became very large and needed capital from outside of members that insurance companies started and these then made it their business to maximise return on capital. Eventually most of the insurance industry has been demutualised, and now serve shareholder interests more than the interests of those they insure. This is one of the reasons why, f or example, in the US, health insurance is so expensive, and why in developing countries there is a lot of repudiation – that is insurance companies use all kinds of stratagems to deny valid claims.

How the present economic system harms the environment

The present economic system is based on reckless exploitation of natural resources – jal, jangal, jameen. Let us start with Jal or water. India has 20 large river basins. As per the Falkenmark Index, 12 river basins are water scarce with less than 1000m3water per capita per annum. The water demand in the country is expected to increase by 34% by 2025 and over 78% by 2034. India’s gross irrigated crop area of 82.6 mha is the largest in the world. A large part of the increase is based on groundwater extraction through borewells.

We have already indicated above how this massive increase in demand for water has been fuelled by the market-oriented agriculture sector. Paddy and sugarcane are both water guzzling crops. But the current economic system continues to promote their production despite the fact that there is serious excess supply of both and excessive consumption of rice and sugar cause public health problems on an epidemic scale. Moreover, the groundwater depletion causes serious environmental imbalance. If economics were a more honest discipline, it would have long ago devised methods to account for these negative externalities and the price of rice and sugar would have reflected those, which would have brought down consumption and production, restoring the balance.

India’s forest land has also gone through significant changes in the last three decades. India lost 668,400 hectares (ha) of jungles on average between 2015 and 2020, In the five years since 2018, India’s environment ministry has earmarked around 88,903 hectares of forest land for non-forestry purposes such as transmission lines, railways, and defence projects. Of this, the largest share of 19,424 hectares was diverted towards road construction, followed by 18,847 hectares for mining and 13,344 hectares for irrigation projects.[6] These diversions are dictated by the demands of the current economic system and ignore the fact that agriculture and livestock rearing are both very dependent on forests. Forests ensure well-distributed rainfall, slow down run off, enhance groundwater recharge and soil moisture and the leaf fall adds humus content in the soil. But the present economic system does not value that as much as timber extracted from forests or minerals dug from beneath forests.

Another example of how the current economic system is pushing us towards destruction is Jameen, or land. According to a survey by the Space Application Centre, Ahmedabad, 97.85 million hectare of India’s landmass which accounts for 29.77% of the total geographical area of the country is degraded. This number was 94.53 mha in 2003-04. The reason why this increase is happening is that only land which has values for maximising return on financial investment is valued. The rest is allowed to erode and degrade.

The degradation of natural capital has led to rural deprivation and loss of livelihood leading to mass distress and out migration from villages. This interconnectedness is not a new revelation, as it has been well studied both from economic and ecological perspectives across the globe. A substantial number in this population moved from rural areas to cities in search of jobs. In the erstwhile natural resource dependent forest areas, the local tribal population sees migration in as many as 60 to 80% households. The total number of migrant population increased from 31.5 crore in 2001 to 45.6 crore in 2011. The degradation of natural capital for economic growth has both social and ecological costs.

As the present economic system has failed, it needs to be changed

The global economy has over the last 50 years become not just inter connected but also has seen large flows of financial capital across nations, sectors, corporations, all in search of risk adjusted maximum returns. While the present system greatly eased the moving of financial capital across national borders, often to tax havens, making the rich investors richer, this globalised economy has failed the common people. While the living conditions of a vast majority of the world’s population have improved in the last century, at the same time concentration of wealth has been exponential, leading to increase in inequality.

In 2022, fully 82% of all incremental wealth generated, accrued to the top 1% of asset holders. These people need to reinvest their money and they only do so in projects which generate high financial returns, but have no or dubious social value, such as gaming software or luxury travel. At the same time, there is a desperate shortage of capital for socially useful investments such as vocational education or mass transportation, and environmentally useful projects like renewable energy generation or solid waste management. Philanthropic grants and social impact investments are a minor palliative.

The Indian economy has become a replica of the global economy steadily since 1991. After the opening up of the economy to foreign investment, and the signing of WTO agreements to permit import at very low tariff rates, the Indian economy has seen a steady decline in the small scale manufacturing sector. While liberalisation increased growth of the GDP, it unleashed severe levels of inequality, which has risen sharply over the last three decades. As per OXFAM Inequality Report, [7] “The top 10% of the Indian population holds 77% of the total national wealth. 73% of the wealth generated in 2017 went to the richest 1%, while 670 million Indians who comprise the poorest half of the population saw only a 1% increase in their wealth. Between 2018 and 2022, India produced 70 new millionaires every day. Yet 63 million Indians are pushed into poverty because of healthcare costs every year.”

This kind of unacceptable inequality is the direct outcome of the current economic system. Yet we have come to know that instead of transforming the economy to become pro-poor, pro-women, pro-employment and pro-nature, the Niti Aayog is working on a perspective plan to grow the GDP from the current USD 3 trillion to USD 30 trillion by 2047. This kind of pursuit of growth at the cost of humans and the environment is completely wrong and must be opposed, but by offering a constructive alternative.

The Alternative – the Economy of Nurturance and its characteristics

As endless growth is neither possible nor desirable, we have to move the economic paradigm from unequal and non-sustainable growth to inclusive and sustainable well-being. To do so, we have the move the system from an economy of exploitation of human and natural resources to an economy of nurturance where humans and nature are cared for as a principle. Growth for its own sake will be eschewed in favour of growth as a basis for more equitable distribution of well-being. Growth will eventually be replaced with sustainability when the economy becomes almost fully based on renewable sources of energy and recycling of materials. The economic model will thus move from the linear to the circular.

There is thus a need for transforming the present exploitative economy into an economy of nurturance, one which ensures dignified lives and secure livelihoods for all and conserves the environment, so that the future generations of humans and species other than the Homo sapiens can survive. This economy of nurturance forms the basis for more harmonious social relations at all levels, from the intra-family to the international level.

We envision a transformation from the current exploitative economy to an economy of nurturance, a phrase used by late Elaben Bhatt, the founder of the Self Employed Women’s Association (SEWA). Though the term is different, it very much echoes the ideas expounded by many others. JC Kumarappa, who wrote a book titled the Economy of Permanence in 1943; EF Schumacher, whose 1974 book was called Small is Beautiful – Economics As if People Mattered, and the Club of Rome sponsored MIT study titled Limits to Growth, published in 1976, which showed that the pursuit of endless economic growth was not even feasible, leave alone desirable. Many of these people were influenced by Mahatma Gandhi.

Exploitation means running an enterprise or an economic process to maximise return on financial capital and to do so, extracting a surplus to such an extent from human capital (labourers and other employees), social capital (community and its institutions). natural capital (land, water, energy sources, minerals, materials) and physical capital (buildings, machinery, equipment) that their ability to remain productive gets impaired. Thus to continue to derive a return on financial capital, the next cycle has to be more exploitative, till it becomes no longer possible to extract more. At that stage the “worthless” factors of production – the exhausted labourer, broken trust and collaboration, depleted groundwater and overused machinery, are thrown away, while financial capital and its owners move on.

In contrast an economy of nurturance is one in which human beings are valued and paid fair wages. Trust and collaboration among them is encouraged and civilised norms of behaviour develop, that lead to evolved institutions. Natural resources whether land, water or minerals are handled with care so as to maintain their productivity over generations and physical capital like building and machinery are well maintained. This means return to financial capital may be a little lower in the short run. In the long run, however, as all other dimensions of the economy do well, the economy takes off into a virtuous cycle. All forms of capital – natural, human, social, physical and financial – are deployed in a balanced manner. The goal is not to maximise return on financial capital but to maximise well-being of not just the greatest number but of the weakest, paying attention to the Antyodaya principle.

Thus an economy of nurturance is one where

- Human beings are valued not just as producers or as consumers, but for being the very basis for which any economy, society or polity should exist

- Trust and collaboration are encouraged, as a first step to building healthynorms and then these evolve into institutions for ensuring maximum human welfare in the community

- The environment is cared for and pollution and waste are minimised and “reduce, reuse and recycle” become the predominant way of production and consumption.

The economy of nurturance is based on Anubandh, another term Elaben used to signify a contract, a bonding with the local economy in terms of relationships which are not just transactional. Apart from local production for local consumption, thereby decentralising the economy, it is also circular in nature and values reproductive functions as much as production, thereby valuing women’s contribution. Finally the economy is sensitive to nature, to the rights of other species and of the future generations.

Ensuring adequate incomes for all through secure jobs by 2034

The first step to build the economy of nurturance is to ensure that in the coming decade, everyone gets full employment. For this, the economy needs to generate about 12 crore new jobs by 2034 and increase the wage rates, incomes, security and dignity of about 50 crore of existing jobs. Before we go into the question of how to do so in the section 3 of this paper, let us get a more detailed idea of what the economy of nurturance will look like in 2034, first in words and then in numbers, summarised in a table.

India’s population in 2023 is 141 crore and it is projected to rise to 147 crore in 2030 and then to 151 crore in 2034, which will still not be the peak. The additional human beings will need not just food, clothing and shelter, but also other basic services such as water, electricity, transport, communications, health care and education. In addition, they would need to have some community and social life, partake in religious and cultural activities and also in governance and political processes. How can this be organised?

We know from data that about two-thirds of the population is of working age that is from 15 to 64 years. By 2034 that will mean 100 crore people. However, the Labour Force Participation Ratio (LFPR) in India has been low compared to other developing countries and has been declining steadily. The LFPR is the share of the working-age population (aged 15 years and above) that is employed or unemployed, willing and looking for employment. In 2022-23, as per GoI PLFS data, of all the Indians aged 15 years and above, only 54.6% were even asking for a job. Among men, this proportion was 77.4% and among women, 31.6%.

There is no likelihood of this trend reversing unless the structure of the economy is significantly changed towards a more labour-intensive and geographically decentralised mode of production, away from metros and cities, with particular attention to the needs of women who continue to bear the twin burdens of reproduction and domestic work.

If we make the assumption that indeed we will be able to alter the structure of the economy in that direction, we should be able to see the LFPR go up to 65%, with male LFPR at 80% and female LFPR at 50%. This gives us the basic data to build a picture of the economy in 2034 – a total population of 151 crore, of whom about half will be rural residents and the rest urban. Of the 151 core, about 100 crore will be of working age -15 to 64 years. Given the LFPR of 65%, we would need about 65 crore jobs, about half in rural India and the rest in urban. If that level of LFPR is desired for India in 2034 then the economy has to generate nearly another 12 crore jobs in the next ten years and improve the income levels in the existing 50 crore workers who are today in the agricultural and the informal sector, out of the total 53.8 crore workers in 2023.

In terms of jobs in various sectors, the primary sector (agriculture, animal husbandry, fishery, forestry, mining and quarrying) will have to account for only 40% of the total employment, down from 57.3 % at present. About 25% (up from current 17.6%) of the total workforce will be employed in the secondary sector (manufacturing, construction, electricity, gas and water) and 35% (up from 25.1%) will have to be employed in the service sector (wholesale and retail trade, storage and transport, communications, education, health, administrative and financial services, business and personal services. In terms of numbers, of the total 65 crore workers in 2034, 26 crore will be in the primary sector, about 16 crore in the secondary sector and about 23 crore in the tertiary sector.

Workers would be adequately paid, with wages or income which permits a decent standard of living of self and immediate dependents. This means that per capita income which was about Rs 98000 per annum in 2022-23 (at 2011-12 prices) will have to more than quadruple to about Rs 4 lakh per capita per annum in 2034 (at 2011-12 prices).

We now look at how the proposed economy of nurturance will generate about 12 crore new jobs required by 2034 and also improve the quality of wages, social security and working conditions in the existing 50 crore agricultural and informal jobs out of the total 53.8 crore jobs in 2023.

Primary sector will continue to be an important source of employment

To help farmers and agricultural workers earn in the lean season, the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) and the MGNREG Scheme was launched in 2006. Cumulatively, since 2006, the MGNREGS has generated 3130 crore person days’ work with a total expenditure of Rs 6.27 Lakh Crore or an annual outlay of less than Rs 40,000 crore per annum since 2006. Only in the COVID pandemic year of 2021-22 the outlay of MNREGS crossed Rs One lakh crore.Even in the peak demand COVID year of 2021-22, the record MGNREGS outlay was less than 1% of that year’s GDP.

In 2022-23, there were about 25 crore workers looking for work which would have paid them just about Rs 200 per day which is below the minimum wage. Yet 39% of these workers did not get a single day’s work in MGNREGS. The reason was simple – inadequate outlay of MGNREGS.

The MNREGS outlay will have to be enhanced in the ten year period from 2024 to 2034, to regenerate the natural resources – jal, jangal, jameen. This work itself will generate five to six crore jobs per annum for ten years but once these resource regeneration work is largely done, these jobs will reduce. However, due to the increase in the availability of water, better soil and renewed forests, productivity will increase in crop cultivation, animal husbandry and fishery and forestry. Jobs in mining and quarrying would also continue to exist even as sustainable and environmentally friendly mining techniques get deployed. Despite all this, there will be decline in the workers in the primary sector to 26 crore from about 30 crore workers at present, and the share of employment in the primary sector will reduce to about 40% by 2034. This will lead to higher wages in the primary sector.

Secondary sector employment based on decentralised small enterprises

The reduction in jobs in the primary sector will be compensated for by increase in the share of employment in the secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy, provided policies are adopted to incentivise employment-generating technologies. The manufacturing sector will have to be significantly transformed to become employment generating. It will be small scale, using appropriate technology, reflecting the capital labour endowments of India. Manufacturing of this kind can be decentralised, catering to local demand and using local and recycled materials and local labour. To ensure that in the transitional period these enterprises remain competitive, a scheme of Employment Linked Incentives (ELI) will have to be be offered by the government from 2024 to 2034.

Still, there will have to be some high tech manufacturing for producing strategic economic needs, mostly using capital intensive techniques. Such industries would be incentivised to pay full attention to occupational safety and health of workers, and the environment. They would be incentivised to use recycled and local materials and renewable sources of energy. Best practices such as the Kaldundborg Symbiosis in Denmark will have to be encouraged for these industries to transition to the economy of nurturance.

The construction sector, which is by nature labour intensive, local and decentralised, will also be incentivised to be environmentally conscious and use green building materials and pay full attention to occupational safety, health and environmental standards. The utilities sector, particularly energy generation, is a major cause of carbon emissions and it will be seriously mitigated by switching from coal to renewable sources of energy, in which India has already made impressive gains. The carbon credit trading system that has been put in place in 2022 will further encourage this.

By 2034, about 16 crore or 25% of the total jobs will be from the secondary sector, which includes manufacturing, electricity, gas and water, and construction.

Tertiary sector employment will reflect the new circular and care economy

The tertiary sector comprising various types of services including Repair and Recycling Services, Wholesale and Retail Trade, Transportation and Storage, Accommodation and Food Services, Education and Skilling, Healthcare and Human Services, Information and Communication, Business and Financial Services, Governance and Admin Services and Personal and Miscellaneous services. The role of the service sector in building an economy of nurturance will be central and would directly feed into it – education and skilling services, healthcare and human services and repair and recycling services. Employment conditions vary widely – from the high end, envy of all – the Information Technology sector, all the way down to casual workers who work in sanitation and sewage, some even engaging in manual scavenging. There are numerous casesof deaths of workers while cleaning sewers. This will be completely unacceptable as we transition out of the present economy. As per the ILO, India had only 3.8% of all workers as government workers, in contrast to 28% for China and 9.5% for Indonesia. Thus government workers will also increase. With all these additions, of the projected 65 crore jobs in 2034, about 23 crore or 35% will come from the tertiary sector.

Well-being, equity and environmental sustainability

Well-being, equity and environmental sustainability will be three anchors of the economy of nurturance. We have identified measurable parameters to describe these in detail. We begin with population and key economic parameters, such as employment, incomes, poverty (Multidimensional Poverty Index with headcount % and deprivation intensity %) and inequality (Gini ratio of income and wealth distribution). In terms of well-being, we have included the human development index which already includes infant and maternal mortality, and educational attainment, particularly for women. There are also well-being parameters such as percentage of children under 5 who are stunted and percentage women reporting domestic violence

We have identified measurable parameters to capture the extent of social capital in the economy, such as the percentage of women who are in self-help groups and the number of Civil Society Institutions (CSIs) per lakh population. Environmental parameters included the extent of forest cover, ground water use versus recharge, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions per capita and the extent of renewable energy as a percent of total.

Phased Transition to the Economy of Nurturance

To move from the present economy of exploitation of human, social and natural capital for maximising returns for financial capital, to an economy of nurturance of human beings, communities and the environment, we need at least a decade. For the purpose of planning, we are dividing this into three phases. In the first phase 2024-2029 – the new government must be persuaded to significantly enhance outlays for ensuring short-term MGNREGS type of employment for rural unskilled workers in crores, while ensuring that jal, jangal, jameen are regenerated. The new government must be persuaded to investment in nutrition, health, education and skilling so as to build human capital. To make small and medium enterprises more employment oriented, the government should also start an Employment Linked Incentive program. In the second phase of five years 2030-2034, lasting institutional solutions will be devised and put in place for identifying obstacles and gaps, investing in solutions to overcome these and building permanent teams which will work to strengthen the movement towards a nurturant economy. In the third phase from 2035 to 2047, deep structural changes will be made to transform the economy from exploitation to nurturance.

How to Build and Economy of Nurturance?

To move to the economy of nurturance, we do need growth, but growth that promotes employment, at wage rates which enable a dignified life for all workers. We also want an economy which is initially less damaging to the environment and eventually conserves it.

To achieve this transition from the exploitative and unsustainable economy of 2023 to an economy of nurturance in 2047, we need to make a set of investments in the following:

- Human Capital – Nutrition, Health, Education and Skills to maximise the realisation of everyone’s innate potential

- Social Capital – From Neighbours to Norms, emphasising Caring and Collaboration

- Natural Capital – Jal, Jangal, Jameen, Jeev Jantu, Jalvayu and building a circular economy so that materials are recycled.

- Financial capital – this potent weapon for change will have to be wrested from the hands of self-serving elites and put to use for increasing overall well-being

The challenge to the present economy has to be first and foremost ideological, as it requires a fundamental change in the value systems of the prevailing elites and transmitted by them to the masses who also then emulate the same values, through psycho-cultural hegemonic processes.

Even knowledge systems are twisted to suit the prevailing political economy. Thus, the first step of change will have to question those knowledge systems which justify the economy of exploitation as axiomatic, as a derivative of human nature, when it is actually a product of bad economics and bad accounting. The disciplines of economics and financial accounting have a lot of corrections to do, which we touched upon earlier.

Regenerating Natural Capital – Jal, Jangal, Jameen, Jeev Jantu, Jalvayu

We need to convert the existing body of knowledge on climate change and environmental degradation into a powerful critique of the present economic system. Then we have to advocate that public investments must be made urgently in regenerating our natural environment. Much of the investment in regenerating common lands, water bodies and forests will have to come from the state.

According to a study carried out by The Energy and Resource Institute (TERI) in 2018, the land degradation through various processes in India cost around 2.5 per cent of the country’s GDP (at 2014-15 prices). The study further concluded that India needs Rs 2.95 lakh crore (2014-15 prices) to reclaim the already degraded/deserted landmass of the country.

The National Biodiversity Authority in 2019 calculated estimated that various public schemes related to sustainable environment require yearly investment of Rs 1.16 lakh crore, versus 0.28 lakh crore actually spent. All these investments will have to largely come from the State, since these are all public goods.

The implication is that if we have to go beyond government funds for natural resource regeneration, we could establish a system of raising capital by “pledging” the cash flows that will come from ecological services of living trees and flowing rivers, not felled timber and dammed rivers. The carbon credit market is already close to USD 800 billion a year and this additionality could take it to trillions of dollars. In the meanwhile, penalties on exceeding GHG emission limits could be deployed for forest regeneration.

Jal – Water

Agriculture is dependent on water supply – primarily rainfall, and then from its storage in surface structures as well as in underground aquifers. Reduction in rainfall in many regions over the last few decades, coupled with peak seasonality of rain in other regions, causing floods and run-off to the sea, has led to the paradox of simultaneous water excess and scarcity in the country, sometimes in the same month across regions and definitely across months in the same region.

The average state of ground water extraction in India is about 63%. According to the estimate of the Central Ground Water Board, the total demand for water in India is expected to be 1093 BCM in 2025 which will increase to 1447 BCM in 2050. As against this, the fixed utilizable water in India stands at 1123 BCM from all kinds of sources (surface and groundwater). In decade from 2024 to 2034, adequate capital will be deployed along with appropriate technology, and suitable regulatory and facilitative institutions will be established, to conserve all water resources, surface and underground.

Jangal – Forest

Forests are a critical resource for the majority of people living in this sub-continent indirectly. But for many the dependence is more direct. Out of a total of 600,000 plus villages in India, nearly 173,000 villages are located in and around forests. These villages are dependent on forest for collecting non-timber forest produce (NTFP), fuel, fodder, cattle grazing, water, timber etc. These forest dependent villages have over 200 million people living in them. In the nurturant economy, return on this investment on forests will come not by cutting trees and selling the timber but by saving the trees and biodiversity in situ and getting paid for ecological services such as carbon sequestration or species preservation.

In the period from 2024 to 2034, all forests whether state owned or community or privately owned will be conserved and for this adequate capital will be deployed along with appropriate technology, and suitable regulatory and facilitative institutions will be established. Eventually in the nurturant economy, all forest resources will be used only sustainably.

Jameen – Land

Currently, agricultural land accounts for nearly 49% and forest land comprises 23% of the total landmass. However, drastic changes were recorded in the quantity and quality of agricultural land and forests in India in the last few decades. Their degradation has adversely affected other natural resources such as water, wildlife, biodiversity and climate. Regeneration of soil and wasteland of various kind will not only improve the environment but will generate jobs in the long run as land productivity will go up and a number of new crops including horticultural ones can be produced on the erstwhile unused land.

Investing in Human Capital – Nutrition, Health, Education and Skills

We envisage that fully 3% of the GDP will be spent on healthcare including nutrition, and 6% of the GDP will be spent on school education and higher education including vocational education. Moreover this will be achieved in the ten year period from 2024 to 2034.

India’s planned development trajectory after independence in 1947 has an important place for education and health. The first national education policy of India was enacted in 1968 and the first national health policy was issued in 1983. Both of these crucial policies have been updated several times since their inception. India renewed its health objective in 2017 and educational objectives in 2020 by adopting fresh national policy documents. Both of these policy documents raised concerns about low public investment and promised adequate public investment to strengthen the health and education system in the country.

Private share of expenditure for health is very high in India. Realizing this, the National Health Policy, 2017 envisaged a decrease in out of pocket expenditure on health care from the current 60% to 30% by increasing public health expenditure. India is short of nearly 0.2 million medical/paramedical professionals in rural health institutions. Moreover, a huge shortage of health institutions in rural areas deprives underprivileged communities.

The New Education Policy, 2020, reiterates India’s old promise of investing minimum 6% of GDP on education. The National Health Policy, 2017 had promised to increase public expenditure on health to 2.5% of the GDP in a phased manner. However, this promise has not reflected in the public spending after enactment of the policy. Though the primary school enrolment rate is now nominally near 100 percent even in poor states, and the secondary school and college enrolment has shot up, particularly for girls, the facilities are woefully inadequate and there is a shortage of properly remunerated teachers. India is short of nearly one million teachers in schools and colleges.

Public investment on health and education in India has always remained lower than not just developed countries but developing countries with large populations and comparable income levels such as Indonesia and also of others in the region such as Sri Lanka and Bangladesh. To improve healthcare and wellbeing, India requires more investment to build more health facilities in rural areas, recruitment of medical and paramedical human resources in rural areas, and availability of medicines and ambulances. Similarly, for improving education, investment is required for the construction of more schools, developing necessary infrastructure in new and old schools, sanitation, drinking water, and for teacher recruitment, salaries and teacher training.

Though there is no doubt in our minds that the investment in these human development sectors should be by the State, it does not mean that this should be spent through government channels. It is one thing to say that school education should be universally free and state funded and another to say that every school should become a government school or every teacher should be a government employee. We must get commensurate outcomes.

Investing in Social Capital – norms for caring, sharing and collaboration

Investing in human capital is not enough if those human beings, even though healthy, educated and skilled, do not trust each other nor know how to work with each other. Due to the upsurge of caste system, the erosion of inter-communal harmony and rise in migration from native places to strange towns, social capital has got eroded and needs to be rebuilt.

One of the aspects would be to ensure occupational health and safety and social security for workers. Sadly, the proposed new Labour Codes, instead of strengthening regulations for occupational health and safety and social security, are more focussed on increasing labour productivity, and flexibility in hiring and firing. In other words, adding another layer of legitimised exploitation though there are some contrary trends such as the enactment of the Rajasthan Platform Based Gig. Workers (Registration and Welfare) Act, 2023. We will have to design the economy to ensure dignified, secure, adequate paying jobs for all who need it. Trade Unions will have to be encouraged as the social capital of the working class.

Another form of social capital is cooperatives. One well known example is the successful AMUL dairy cooperative movement. While cooperatives have done well in some states and some sectors such as dairy in Gujarat and sugarcane in Maharashtra, there is a need to revive this sector as an integral part of the economy of nurturance. Cooperatives differ from companies in the sense that capital is only contributed by members (such as milk producers or sugarcane farmers). Thus the surplus in the form of profits is distributable only to members, who have a stake in the enterprise beyond just financial capital. Incidentally, Producer Companies also follow the same principle and thus are cooperatives in spirit, but incorporated under the Companies Act. The economy of nurturance should do all it can to move as much of the economic activity into the cooperative sector, so that the ills of capital concentration in the hands of a few private individuals are curbed.

Another example of new form of social capital is the women’s self-help group movement, which done a lot for women’s empowerment, all the way from Kerala to Bihar. We can learn from this 15 crore strong women’s movement, which mobilised over one lakh crores of women’s own savings and leveraged bank loans several times their own savings, so that the total outstanding loans to the SHGs are over Rs six lakh crore by Mar 2023. The SHGs are the neighbourhood sandboxes for women to come out of their homes and learn to interact and transact. Over the last three decades, crores of women have taken loans, first from their SHGs and then from banks through their SHGs, and started micro-enterprises. Thousands of SHG leaders have been elected to gram panchayats and some even to block panchayats and Zilla Parishads.

Civil society institutions (CSIs) are another form of social capital that India has had a long tradition of. While many CSIs are engaged in relief, welfare, development and environmental work, others are advocates of the excluded and the oppressed. These CSIs naturally come into conflict with the state. Under all regimes, the state has tried to curb CSIs. This trend must be reversed as CSIs are the major building blocks of social capital. CSIs must be seen as the balancing force in the tug of war between the state and market actors.

SEER Districts to ensure jobs for all and high HDI

India has about 800 administrative districts for a population of 143 crore in 2023, or an average of 17.4 lakh people per district. With some more splitting of districts, we are likely to reach a level where there will be roughly 15 lakh persons in each district, about two thirds of those in rural parts, except in highly urbanised districts split from a few large cities. Instead of following administrative boundaries, we propose the boundaries of districts be based on natural features like rivers, hill ranges, or in case of large plains, socio-cultural factors. This exercise should aim at establishing about 1200-1500 Socio-Economic Ecological Regeneration (SEER) Districts, each having a population of 10-15 lakh persons by 2034.

Based on the monthly per capita expenditure data collected last in 2011-12 by the NSSO, we can look at the consumption pattern of the persons living in any average rural-urban district. We find that nearly half of the monthly per capita expenditure goes on food, including cereals, pulses, edible oil, salt, spices and sugar, vegetables, fruit, milk and dairy products, eggs, fish and meat, tea and coffee, pan and tobacco and intoxicants. The other half goes on non-food expenditure, including clothing, footwear, rent, electricity, water, transport, fuel and gas, education, entertainment and medical treatment, and consumer durables.

What is most notable is that of the above consumed items in any district, with the exception of about 15-20% of the total, the rest are already produced or can be easily produced in the district itself. Very few items such as salt, some spices, pan and tobacco, petroleum fuels, electricity, a few medicines and some consumer durables, need to be brought from outside the district. With advances in solar energy generation, electricity need not be imported and even petroleum fuel based vehicles can be replaced by electric vehicles. Thus the Gandhian ideal of “self-reliant villages” can be realised in the form of self-reliant SEER Districts which can promote a number of enterprises to produce what is locally consumed, while generating employment locally where it is needed in rural areas and nearby small towns.

Most of the less developed districts have credit-deposit ratios of 30-40% which shows that a lot of the local savings go out of the district through the commercial banking system. Thus finance for the local enterprises can be garnered from local people’s savings by SEED level Banks on the lines of Small Finance Banks and the earlier Local Area Banks. The current District Central Cooperative Banks should be left alone as they are government controlled.

The SEER Districts should also invest in education, skilling and healthcare services and infrastructure using the Zilla Parishad budget. This way they can make a tangible contribution to the human development index (HDI) of the district.SEER Districts will have all the physical capital – industrial sheds, warehouses, roads, water supply, electricity and telecom infrastructure, to ensure support to manufacturing and service enterprises. Adequate housing will have to be provided to the workers. To ensure regional integration, SEEDs which fall under an ecological zone like river basin or a recognised socio-cultural zone (such as Doaba in Punjab or Rayalseema in AP), may form regional councils for coordinated development across SEER Districts. We also suggest that boundaries of electoral constituencies should be coterminous with the boundaries of SEER Districts. This will align the demand for developmental inputs with the political process.

Requirement of Financing and Where Can it Come From

Now we turn to the question – how would this be paid for and by whom? We have identified several different types of funding sources. The fixation with the government having to fund everything will have to be given up. We must use the extensive financial resources with banks, the corporate sector, communities and even individual households. The top 10% of the Indian population holds 77% of the total national wealth. 73% of the wealth generated in 2017 went to the richest 1%, while 67 crore Indians who comprise the poorest half of the population saw only a 1% increase in their wealth. Thus internal wealth transfer is a must.

Building an economy of nurturance will require an annual investment of about Rs 300 lakh crore over a ten year period. This need to be spread evenly and can rise from Rs 20 lakh crore per annum from 2024 to Rs 30 lakh crore by 2029 to Rs 40 lakh crore by 2034. This way it is less than 8 % of the GDP of any year. Given the “public goods” nature of these investments, the government will have to bear a significant share of this. However, we have suggested several alternate sources of funds, including bank loans and community and individual investment. Thus the government share of this will be about two-thirds or 5% of the GDP which is about one third of the government budget.

Requirement of Investment for dignified jobs for all by 2034

To move towards an economy of nurturance, the next government when it comes to power in 2024 must be persuaded to invest along the priorities discussed above in the next decade.

| All figures In Rs Lakh Crore

Purpose of Investment |

Investment required from 2024 to 2034 |

| Regeneration of Natural Resources – jal, jangal, jameen | 24 |

| Agricultural diversification and value chains /collectives | 16 |

| Infrastructure in district and small towns | 40 |

| Education and Skill Development | 40 |

| Nutrition, Health care & human services | 20 |

| Employment Linked Incentive (ELI) for MSMEs in non-metros | 100 |

| Repair, Recycling and Renewable Energy enterprises | 60 |

| Total in Rs Lakh Crore in the ten years 2024-2034 | 300 |

The total investment from 2024 to 2034 is estimated to be Rs 300 Lakh Crore. As the investment has to be concentrated in the next ten years, 2024 to 2034, it amounts to Rs 30 lakh crore per annum. This is less than 8% of the projected GDP in 2024 and will be as low as 4% of the GDP in 2034. The investment levels in the economy are likely to go up from the current 30% of the GDP and government expenditure will also go up as the tax to GDP ratio raises from the current 16% to perhaps a more appropriate 25-30%.

The good news is that much of the investment is not expected from the Government. The rest will come from other sources listed above, namely Households, Community Collectives, Corporate CSR, Banks/financial institutions, and Corporate Investments. In the table above, we have indicated that while the government will have to play a major role in financing of regeneration of natural resources, infrastructure and education and health.

Public expenditure needs to be made more efficient and outcome oriented. Moreover, public expenditure should largely be aimed at the disadvantaged groups. For example, expenditure on public financed professional education is not as welfare promoting as that same expenditure on universalizing primary and secondary education. Finally, to ensure sustainability of the public investment, there should be an element of cost recovery through user fees on an affordable basis.

Thus we get the eightfold path for ensuring that there is adequate financing by 2034:

- Enhance the tax to GDP ratio so that there are more resources for public expenditure

- Enhance the share of public expenditure on the regeneration of natural resources and on health, education, and public services

- Increase the efficiency of public expenditure to achieve more outcome for the same level of expenditure

- Increase the share of public expenditure that specifically benefits the disadvantaged groups, so that it becomes more inclusive and equitable

- Mobilise resources from individual households for investments in their own nutrition, health, education, housing, and farm or enterprise improvement.

- Mobilise community contributions, local charities and CSR resources

- Incentivise corporates to make responsible investments locally

- Leverage bank credit significantly as has been done by the SHG movement

To thereafter achieve an economy of nurturance, pertinent to these sectors, new financing models need to be explored and promoted. We suggest some below.

Financing from Banks and Financial Institutions

For investments in agricultural diversification and in micro and small enterprises, the main financing source will be households and banks/financial institutions. India has had a long tradition of using its vast banking system for developmental purposes. In 1980, a program called Integrated Rural Development Program was launched where banks gave loans to government identified families below the poverty line, while the government gave a principal subsidy of between 25 to 50% of the loan. This program has continued by one name or another since then.

Apart from encouraging loans from banks to families below the poverty line, the Government of India and Reserve Bank of India encouraged National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development (NABARD) to take up promotion of women’s self-help groups (SHGs) for savings and credit as far back as 1992. This savings-led microfinance model has now become the largest financial inclusion programme in the world covering nearly 12 crore households. Total bank loans to SHGs on 31 March 2023 were over Rs 80,000 Crore. In addition in the year ending Mar 2023, microfinance loan amounts from channels other SHGs were nearly Rs 2.5 Lakh Crore to nearly 6.7 crore borrowers. This has greatly increased the availability of credit for self-employment, part of which is also used for personal needs.

Another early attempt at using bank finance for what was always dependent on government budget funding was the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) introduced by Dr Manmohan Singh in 1995-96, with an initial corpus of Rs. 2,000 crore given to NABARD. This was used to give loans to state government for building rural roads, bridges, irrigation facilities, etc. The RIDF was topped up every year by mandating banks to deposit in RIDF, the amount of shortfall in their priority sector lending targets. With the allocation of Rs 40002 crore for 2022-23 under RIDF XXVIII, including Rs 18,500 crore under Bharat Nirman from the GoI. The rest being funds from various banks’ shortfall in priority sector lending,, the cumulative allocation has reached Rs. 4,58,411 crore.

To enhance the flow of credit to Micro, Small and Medium enterprises (MSMEs), in April 2015, the GoI launched the Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana (PMMY) scheme for giving non-farm income-generating loans of three categories: (i) Shishu – up to Rs. 50,000 (ii) Kishore – from Rs. 50,001 up to Rs. 5,00,000 (iii) Tarun – above Rs. 5 lakh and up to Rs. 10 lakh. Borrowers could avail loan facility from any Public or Private Sector bank, Regional Rural or Small Finance Banks, NBFCs and MFIs. By mid-2021, over 30 crore loans had been given under the PMMY, worth Rs 16 Lakh Crore. About 68% of the loans were given to women and 51% to persons in disadvantaged categories known as Scheduled Castes/Tribes and Other Backward Classes. Though there are a number of issues with MUDRA loans, we can learn lessons from the massive use of bank finance in this government program.

In a similar way, the PM Awas Yojana for housing is also based on bank financing, with the government only selecting the beneficiaries through target criteria and providing an interest subsidy.

To build the economy of nurturance, we must use the financial capital available with the banking system to encourage the establishment of new generation enterprises. This will greatly enhance the developmental capital which will become available to the new economy, which would be impossible to finance from the government budget. To ensure that this happens in a decentralised way, we have already suggested the formation Banks at the level of the SEER Districts. By 2035, when the third phase begins to transform the economy, social control must be re-established over the banking and financial sector so that the collective savings and investments of Indian people are used for wider well-being.

Individual Household and Community Financing

As nearly half of all workers are self-employed, it is obvious that households remain the largest single investors in job creation for themselves, whether by investing in natural capital, such as land and water development, or in human capital such as education and skill development, or in physical capital such as building and equipment. There were nearly 9 crore farm households in India, of which only two crore had an income exceeding expenditure, as per NSS 2012-13. These farm households made an average investment of over Rs 50,000 per annum per household. However, alarge part of the individual household investment has gone into borewells, which eventually depleted the groundwater. The government can, by changing the policy on groundwater use, encourage farmers to do the reverse – invest in farm ponds, farm bunds and other water harvesting structures, so as to capture rainwater runoff and recharge the depleted groundwater aquifers. Similarly by changing policies on minimum support prices, the government can promote diversification.

Community financing for education and health was well-established as a tradition. Earlier, a large number of schools and hospitals were endowed by wealthy people and run on charitable lines. Similarly creation and management of village ponds, for irrigation, village grazing lands, and village forests was in the hands of the community with the ruler’s local representative acting as an overseer. While some funds did come from the ruler, there was a lot of contribution in terms of voluntary labour and materials. That tradition was eroded as the notion of the welfare state took over after Independence and the government took away all initiative from communities and local elites.

Philanthropic and CSR Financing

The donor and corporate social responsibility (CSR) financing are important financial mechanisms in India, especially for supporting innovative sustainable development ideas. Domestic philanthropic funding has increased from Rs 12500 crore in 2010 to Rs 55000 core in 2018. Out of the total domestic philanthropic fund, 60% came from individual donations. Both national and international philanthropic donor financing have played an important role in the development of the country. Moreover, the size of the fund has also enlarged substantially in the last few years.

CSR expenditure was estimated at Rs 26211 crore in the financial year 2021-22. Over 60% of the CSR fund was invested in sectors like health, education and poverty reduction. Only 6% of the fund was invested in projects related to environmental sustainability. These funds, though much smaller than government funds, play a very important role in testing innovative approaches to development problems.

Though CSR and philanthropic financing is a much smaller proportion of government financing and even lower than what is possible through the banking and financial sector, it is still very useful both for promoting innovations as well as catering to the needs of the extremely vulnerable social groups, who cannot be supported through loans nor are there enough public funds for them.

Public Financing will remain the most important source of investment

Most of the investment requirements are in the nature of public goods – for regeneration of natural resources, for education, nutrition and health, and infrastructure in district and small towns. Here the investment will have to largely come from the state, although the state can be more creative in terms of where to mobilise these resources other than taxes.

Additional resources can come as long term market borrowings, financed by endowment life insurance companies, and also by pension savings funds, both in India and abroad. Already, CALPERS of California, USA and the Quebec Pension Fund of Canada are major investors in India. Additional resources can also come from international institutions such as the Global Environment Facility and the Green Climate Fund.

There are other programs such as agricultural diversification and micro, small and medium enterprises, where the investment has to be by private individuals in farms or micro-enterprises owned by them, and they in turn can be financed by banks.

The relative roles of different kinds of financing for different sectors are summarised below:

Table 1 Estimated Need and Possible Sources of Funds for Jobs for all by 2034

| Source of Funds

All figures In Rs Lakh Crore |

Invest-ment reqd from 2024 to 2034 | Public financing through the Govt budget | Community

Collec-tives |

Corpo-rate CSR | Banks and financial institu-tions | Corpo-rate invest-ments | Indivi-dual House-holds |

| Regeneration of Natural Resources | 24 | Major | Minor | Minor | Minor | Minor | Minor |

| Agricultural diver-sification and value chains /collectives | 16 | Minor | Medium | Minor | Medium | Medium | Minor |

| Infrastructure in district and small towns | 40 | Major | Minor | Minor | Minor | Medium | Minor |

| Education and Skill Development | 40 | Major | Medium | Minor | Minor | Medium | Medium |

| Nutrition, Health care & human services | 20 | Medium | Medium | Minor | Minor | Medium | Medium

|

| ELI for MSMEs in non-metros | 100

|

Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Medium | Medium |

| Repair, recycling and renewable energy enterprises | 60 | Major | Minor | Minor | Major | Medium | Medium |

| Total in Rs Lakh Crore in the ten years 2024-2034 | 300

|

Only a small part of this investment is expected from the government. Rest will come from other sources listed above. | |||||

Building Ideological and Political Support for the Economy of Nurturance

In this paper, we have built on many existing ideologies, policies, programs and schemes, partly to minimise resistance to change and partly to demonstrate that what we are suggesting is already beginning to be done in many spatial locations, many sub-sectors of the economy, and with many segments of the population. Nevertheless, the magnitude of change envisaged is enormous and it will not happen easily. It will be resisted and fought at every step by those who benefit from the present exploitative economy – a nexus of political leaders, capitalists, civil servants, intellectuals and the capitalist and politically controlled media, all duly supported by the upper middle class which has prospered post liberalisation, privatization and globalization.

There is thus no way to bring about the change we desire except by using state power, which will have to be won through democratic means. This implies that building an economy of nurturance will remain a pipe dream unless the political pathway for it is charted and then painstakingly traversed. This has to be done in three steps – first, developing the ideological basis and the supportive knowledge systems for the economic transformation we are seeking. Second, working with leaders of various occupational groups, and third, working with elected representatives and political parties.

Work at the Knowledge Systems and Ideological Level

These serious problems caused by the currently prevailing economic system need to be addressed but these cannot be addressed in a “business as usual” approach any more. Many fundamental characteristics of the economic system need to be changed, and this will have to begin with a revaluation of a lot that is not valued in today’s economics but which is truly of value. We describe some of these below,

Accounting for hidden costs in enterprise profit and loss accounts

The economy of nurturance will question one of the key concepts of economics – profit, which is earnings minus costs. A lot of economic enterprises are profitable because they do not account for a lot of hidden costs, as these happen outside the enterprise’s profit and loss account. Economists call these “externalities”. For example, if an industry releases untreated effluents and pollutes water bodies, it saves on pollution treatment costs and appears to be more profitable while society bears its costs in terms of human health and environmental degradation. Likewise if an enterprise makes its workers work 60 hours a week or in unsafe conditions, they suffer ill-health costs whereas the enterprise becomes more profitable.

The disciplines of Economics and Financial Accounting are guilty of persisting with this falsehood which distorts resource allocation and investment decisions. They need to amend their theories and fully account for all externalities, both social and environmental. The early work done in economics on social cost benefit analysis, which was dropped under the pressure of businesses, needs to be revived. After all, “getting the prices right” is an axiom in good economic management.

We need to amend the laws and regulatory frameworks to account for these costs fully and eventually include those in the enterprise profit and loss account through a system of penalties. Only then will the enterprise owners change their behaviour and stop exploiting human and natural resources – a major step in the transition to an economy of nurturance. We are already beginning to see a change in which environmental costs are being accounted for in the books of the polluting or carbon-emitting enterprises, leading to penalties on them. At the same time, those which are reducing emissions are able to earn from the carbon credit markets due to tradability of carbon credits.

No equivalent of this has yet been established for exploitation of human resources – the reason is not difficult to guess. Carbon emissions are a cross-border phenomenon – climate change effects require no visas. Thus it is in the interest of the developed countries to combat climate change and reduce carbon emissions. But if an enterprise produces other forms of local pollution, it has to be handled by the respective country.

By the same token, if labour gets exploited, there is no adverse impact on the rich either in the home country or in other developed countries. So it will have to rely on moral and ethical considerations. This has led to the rise of movements like “fair trade” but these remain marginal compared to size of the problem. Because India is at the peak of its demographic period when the number of persons of working age is high, this situation of oversupply of labour will have to be tackled through policy. Enforcing minimum wages laws and working condition regulations is a surer way to approach this issue.

However, the four new Labour Codes are actually regressive in the name of “ease of doing business”. Though there is as yet no labour agitation like there was a farmers’ agitation, given the intolerably low levels of wages coupled with inflation, conditions are ripe for a mass labour agitation. It will not be a surprise if the next government, irrespective of the party in power, will have to repeal these four labour codes just as the farm laws were repealed.

Valuing Intra-family human well-being services by women

One of the big problems of the present economy is that it puts a value on goods and services which are exchanged outside the home or family and treats invaluable intra-family services of care giving at zero value. For example, a mother spending all her time taking care of small children will not be treated as gainfully employed in income or employment statistics but if she took even two hours of work as a nanny in someone else’s home, then she is treated as employed and her earnings will be part of the national income.

In the economy of nurturance, there will be a system by which home making and reproductive duties will be valued and accounted for, initially in the form of “intra-family credits” and subsequently become exchangeable for some goods and services provided by the state, such as a state paid vacation for the mother, for example. Thus intra-family work, particularly by women will be valued and counted in economic aggregates. Over time, this type of work will become increasingly exchangeable for other goods and services in a system backed by the state. Imagine what the relative contribution of women and men to the modified GDP will look like then – women’s share of the economy will become much larger than today. Eventually this will incentivise men to share home-making duties and even reproductive functions other than child-bearing. So the transition will be more self-interest driven than based on moral exhortation about gender equality.

Valuing social activities that build social capital

The next innovation in the economy of nurturance would be to value social activities such as care giving outside the family. An early version of this idea was the issue of Labour Notes by Robert Owen’s National Equitable Labour Exchange in Birmingham, England in 1824. In the contemporary times, it is known as time banking. In these systems, one person volunteers to work for an hour for another person; and is then credited with one hour, which s/he can redeem for an hour of service from another volunteer. A simple example of this could be looking after each other’s children by two neighbours.

The next stage would be establishing trustful relationships outside of one’s normal kin or hangout groups and establishing teams comprising diversity of individuals and in collaborating. These will require new norms for measurement and valuation, but once the system settles, it will be a good way to encourage positive social behaviour through economic incentives, something which at present is left to exhortation and moral suasion.

Valuing the environment

Habitat destruction is fuelled by quest for economic growth. This was another example of how the current economic system destroys the environment and eventually the well-being of humans and other species on the planet. According to IUCN, habitat loss and degradation have affected about 89 percent of all threatened birds, 83 percent of mammals and 91 percent of all threatened plants globally. The spread of zoonotic diseases like SARS and COVID is directly attributable to the habitat destruction of species like bats, and they faced overcrowding and sharing habitat with other species, their coronaviruses learned to jump from one species to another and eventually to human beings.

There has been increasing understanding that environmental services provided by natural resources – such as clean air, water, biodiversity, are far more valuable than the material and energy use of the same resources by destroying them. A farmer can cut a teak tree and earn Rs one lakh one time, but if a farmer was paid Rs 8000 per annum for the environmental goods it produces while staying alive, the farmer would rather preserve the tree. This is being done by pioneer organisations like the Sierra Club or The Nature Conservancy, and the idea has taken root and spread.

What is needed is to change accounting systems both at the enterprise level as well as the level of National Accounts, to fully take into account the environmental effects of any economic activity. This should be backed appropriate changes in reporting regulations and laws. Once the financial accounts start disclosing the effects of environmental pollution or conservation, enterprises and governments will become much more open to pressure from concerned citizens and will switch to environmentally sustainable practices over time.

We have outlined earlier some steps above to challenge the prevailing ideological and knowledge systems underpinnings of the present exploitative economy. We would promote vigorous questioning of the hidden biases of economics and the expose the fallacy in trying to maximise financial returns at the (unaccounted) cost of destruction of natural capital, human capital and social capital.

For this universities will be major arenas for debate. We would promote conferences, seminars, debates and periodicals which systematically expose the folly of the current economic system and talk about the economy of nurturance.