Sustainable Growth with Decent Employment – The Challenge for This Decade

Growth Has Not Been Sustainable in the Previous Decade

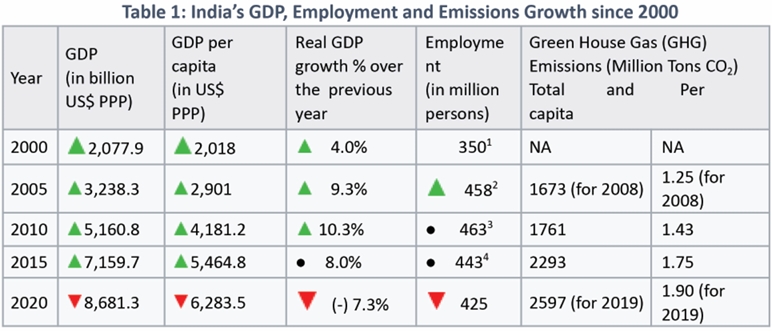

Compared to the high growth in the first decade 2001-2010, when growth rates of the real GDP were close to 10 percent per annum, during the decade starting 2011, India experienced a decline in its GDP growth rate, to 7.99 per cent in 2015 and further to 4.18 per cent in 2019.Then due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting economic downturn, the GDP actually fell in 2020-21. This was the result of the COVID pandemic and its adverse impact on the economy. Table 1 below summarizes the GDP growth and the employment growth rate trends:

Sources: IMF DataMapper https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPSH@WEO/IND, MOSPI (2019) PLFS and CMIE for Employment. https://www.climatescorecard.org/ for GHG emissions data

The compounded average growth rate (CAGR) of GDP in purchasing power parity (PPP) adjusted US$$ was 7.4 percent pa while the CAGR of employment was just 0.98 percent pa. The CAGR of GHG emissions was 4.08 percent pa. In addition to the slowdown in the GDP growth and almost no additional employment, the slowing growth was at an increasing cost to the environment, as evidenced by higher GHG emissions, the steady depletion of basic natural resources – jal, jangal, jameen (water, forest and land) and increasing levels of air and water pollution.Thus the environmental sustainability of even the reduced GDP growth was also questionable.

How Many Jobs and of What Kind Do We Need in India in this Decade?

The Planning Commission had said in 2012 that,“employment elasticity has come down from 0.44 in the first half of the decade, 1999–2000 to 2004–05, to as low as 0.01 during the second half of the decade 2004–05 to 2009–10.” In the period since 2012, India’s employment growth rate fell further. Employment in the Indian economy shrank by 0.2 per cent in FY 2014-15 and by 0.1 per cent in FY 2015-16, according to the India KLEMS database of the RBI.This trend was severely exacerbated in 2020 due to the COVID pandemic’s effects. Using CMIE data for 2020, we estimate the CAGR of employment over the two decades 2000-2020, to be just about 1 per cent pa, despite the GDP CAGR of around 7.4 per cent over the two decades. Thus, we will have to work for the growth of employment, not just of the GDP, in 2021-30.

Five-yearly Employment and Unemployment Surveys (EUS) were conducted by the National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) and the last EUS was for 2011-12. The Government of India (GoI) discontinued the EUS from 2015 onwards and launched the Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) from 2017. The first Annual Report of the PLFS for the period June 2017- June 2021 was officially released in June 2019. The second report based on the survey from July 2021 to June 2019, was released on 4th June 2020.

Using these and other sources, particularly the unemployment reports from the Centre for the Monitoring of the Indian Economy (CMIE), we are able to put together a picture as on December 2020. Applying the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) of 37.5 per cent for age 15 and above, from the PLFS 2021-19, to the estimated Indian population of age 15 years and above at the beginning of 2021, of 1095 million, we can infer that the total labour force was 520 million at the beginning of 2021. Of these, as per CMIE’s moving average, 8.3 percent or 47.3 million were unemployed at the end of Dec 2020.

How many jobs does India need to generate in the decade 2021-2030 to ensure decent jobs for nearly everyone?1 This depends a lot on what number is assumed for the growth rate in labour force participation rate. We believe with the enhanced economic stress due to the COVID pandemic, the declining trend in the LFPR may be reversed as more women and youth enter the workforce to supplement household incomes. At the same time, the increment in the labour force will be lower than in the previous decade, since the population growth rate fell in 2001-2011 decade to 17.64 percent from 21.15 percent in the decade of 1991-2001. Children born in the 2001-2011 decade will be entering the labour force in 2021-2030.

Reconciling these two contradictory trends, we assume the labour force growth will reflect the population growth rate two decades ago. Thus, we project the labour force will go up from 519.7 million in 2021 to 611.4 million in 2030, a net increase of 91.7 million persons. If we instead make the assumption that the labour force will grow at the same CAGR as the 2000-2020 period, which was 1.17 percent per annum, then the labour force will grow to 583.9 million by 2030, still a net increase of 64.1 million.

The CMIE estimated number of unemployed as of 31 Dec 2020 was 47.3 million. Thus, the workforce at the beginning of 2021 was 471.4 million. Now let us compute the work force in

There is bound to be some unemployment at any time in an economy.Assuming a base rate of unemployment of 3 percent of the 611.4 million labour force in 2030, it means 18.33 million unemployed in 2030. Thus, we project the workforce in 2030 to be 593.1 million if we assume the population based CAGR of 1.64 percent or 566.4 million if we go by the 2000-2020 CAGR of 1.17 percent. We are inclined to believe that the LFPR will go up, as the pressure to earn goes up among the youth and women. Therefore, we believe the number of incremental jobs needed in 2021-2030 is 121.7 million. Simply put, India needs to add 12 crore new “decent” jobs (with social security and dignity) in the 2021-30 decade.

We note four facets of the job crisis – not enough jobs overall – within that not enough jobs for youth and women, not enough decent” wage/salaried jobs, not enough jobs in rural areas and small towns and not enough low-skilled and semi-skilled jobs for people emerging from the agricultural and the informal sectors, or those joining the labour force anew.

- Demographically – these jobs are mainly needed for younger workers (15 to 29 years), whose labour force participation rate (LFPR) was 2 per cent, much lower than the LFPR of 49.8 per cent for the overall (15-59 years) population. Also, jobs should be more than proportionately for female workers since their LFPR was also much lower at 16.1% during the July-September 2020 quarter, the lowest among the major economies.

- Occupational status wise, the vast majority of these jobs will need to be either in the form of entrepreneurial self-employment or regular/contract wage/salaried jobs with social security benefits. Working conditions must be improved for those in casual and contract jobs and in involuntary self-employment, to make these into “decent”

- Geographically, more jobs need to be in rural areas and in small towns, at best up to district Larger cities and metros must be toned down as growth magnets.

- There are five avenues with a major job creation potential (a) regenerating jal, jangal, jameen (b) diversified agriculture and localized value added (c) manufacturing at the level of micro and small enterprises (d) construction of housing and infrastructure, and (e) services of all kinds, from trade, transport and storage to health, education and business services.

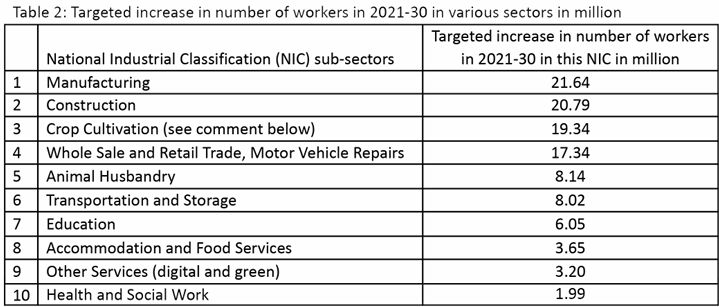

Of the projected 12 crore new “decent” jobs, 11 crore will have to come from these ten sectors:

A question would arise that as the crop cultivation sector is already saturated, how can it absorb another 1.9 crore workers? The details are given later, but the highlight is that the enhanced productivity of Jal Jangal, Jameen will be able to support these additional workers.

Targeted Growth in Jobs by Various Categories to Ensure “Full” Employment

More Jobs for Youth

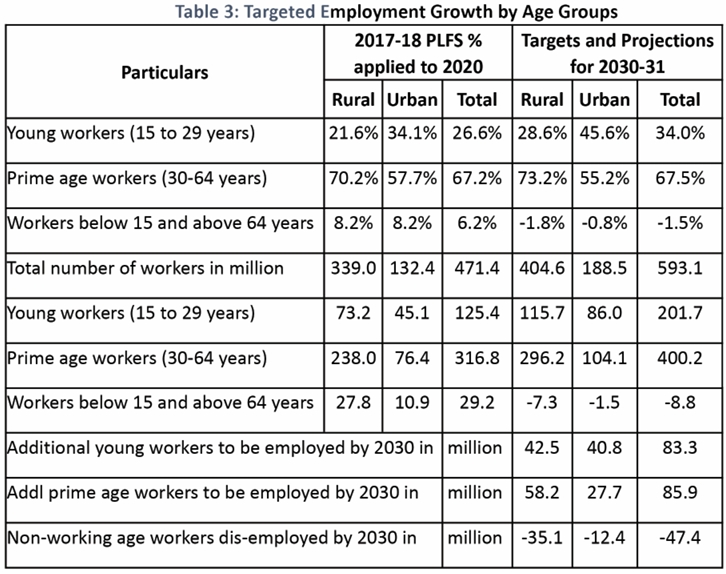

We not only have to worry about generating 12 crore new “decent” jobs in total, but also have to ensure that the growth of jobs for younger workers (15-29 years of age) grow faster than those for workers in the prime age of 30 to 64 years. We also have to ensure that numbers of those who below 15, child labour, and those above 64, working for survival, must come down.

Accordingly, we have put certain aspirational targets (see Table 3 below) for higher growth of 83.3 million in employment for the young age workers and actually a decline in employment of 47.4 million non-working age persons.

Source: Author’s computations based on aspirational targets for 2030, using PLFS 2017-18

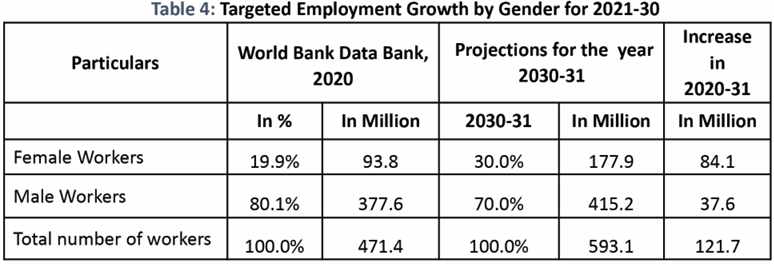

Many More Jobs for Women

Likewise, the growth of jobs for women workers needs to be more than for men. We have given an aspirational target here of the share of women in the workforce going up from 20 to 30 percent in this decade. This will increase the number of female workers by 84 million in the decade. (See Table 4 below). This will require a number of gender specific strategies.

One of the ways to enable more women to work is to make public investments in more opportunities for school and college education for girls, in commuter transportation from rural areas to small towns as they become job growth centres, in working women’s hostels in cities, and in establishing mandates childcare facilities at or near work places.

Source: Author’s computations based on aspirational targets for 2030, based on PLFS 2017-18

More Jobs for Semi-Skilled and Higher Skill Levels

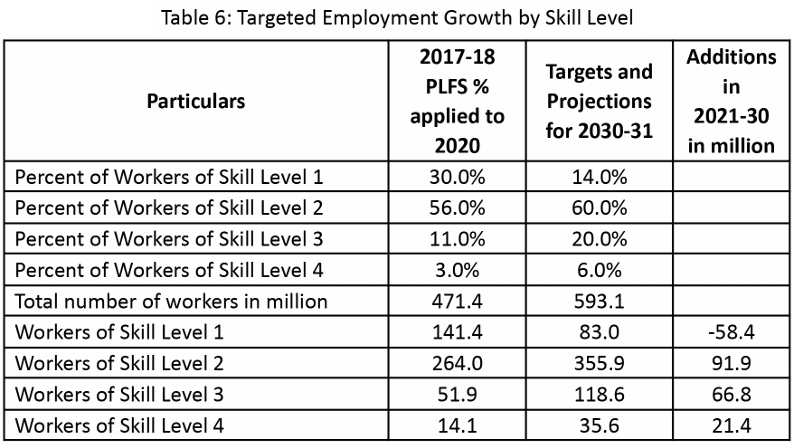

The National Skill Qualification Framework defines multiple skill levels from 1 (workers who only have manual and routine skills to 4 professional workers). The growth of jobs for skill level 2 and 3 workers and for level 4 will be higher as the economy makes the transition to a middle-income status in the coming decade.

Accordingly we have suggested targets for these three levels higher than 2020 levels. In contrast we are planning for a decline in the share of level 1 workers, particularly as these jobs are most likely going to get eliminated by automation and artificial intelligence.The skill level 1 workers are proposed to graduate to skill level 2, whose numbers need to increase by 91.9 million by 2030.

In addition, the workers at skill level 3 and 4 also need to increase by 66.8 and 21.4 million respectively. Thus increasing the number of skilled workers by 180 million is the national skilling target for this decade.

Source: Author’s computations based on aspirational targets for 2030, using PLFS 2017-18

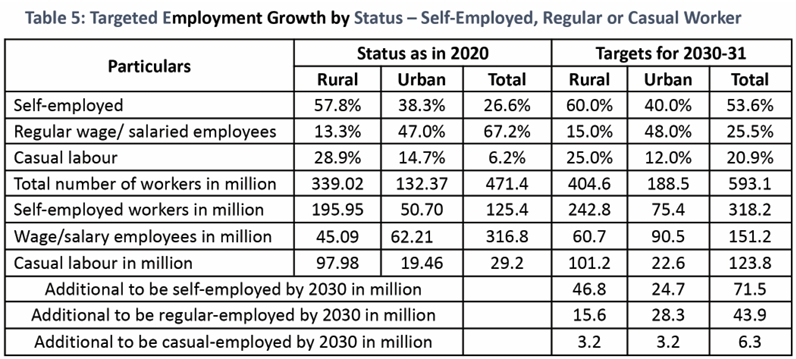

Focus on Entrepreneurial Self-Employment and Regular Wage/Salaried Jobs

The growth of jobs should be first and foremost through entrepreneurial self-employment. Here we draw a distinction between “voluntary” self-employment versus “involuntary” self- employment. This exigencies of choice of occupational status has been discussed in detail in the literature, most recently by Karaivanov and Yindok (2022), to classify entrepreneurs as involuntary and voluntary. Involuntary self-employment is a last resort for those who are not even able to get casual wage work.

Thus the strategy for India in this decade should be to promote a large number of enterprises, at a scale slightly larger that “own account enterprises”, a lot of which are actually involuntary enterprises. Interestingly, there exists a large body of theoretical and practical work which shows that individuals with a high achievement motivation can be identified and trained to become voluntary entrepreneurs. (Miron and McLelland, 1979). Once a large number of entrepreneurial individuals establish voluntary enterprises, they will grow and create jobs for regular wage and salaried workers. This will then lead to a decline in the share of casual workers, though their absolute number will grow marginally. (See Table 5).

Source: Author’s computations based on aspirational targets for 2030, using PLFS 2017-18

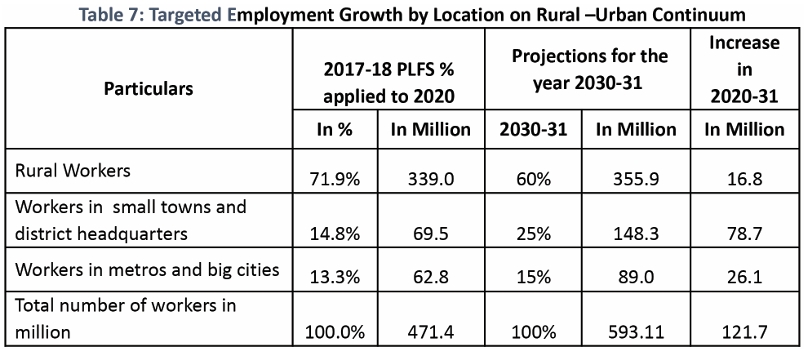

More Jobs in Rural Areas and Small Towns

As the rural population is still about two-thirds, we not only have to plan for generating 12 crore more jobs in total, but also have to ensure that the growth of jobs for urban (small town and district HQs) is higher than for metros and also for rural areas. We recommend an aspirational target that by 2030, as much as 25 percent of the workforce being in small towns and district headquarters, as against a mere 14.8 percent now. The workforce in small towns and district headquarters needs to rise by 79 million. We need a policy to improve spatial distribution of jobs. Till that happens, metro and large cities will remain growth magnets and led to a lot of involuntary migration.

Source: Author’s computations based on aspirational targets for 2030, using PLFS 2017-18

Five Avenues with Major Employment Potential Over 2021-2030

The question is whether such a large amount of decent employment can be created, given the dismal history of this decade so far? It is not enough to merely say a resolute yes. We need to answer in what sectors of the economy can these jobs be created? And with what level of investment? And where will all that capital come from? And recognizing that capital is not enough, policies and institutions will also have to be reshaped to ensure that the investments yield the desired number of jobs and with decent wages. Before we attempt to answer the questions about capital, policies and institutions, let us list the sectors which have the maximum potential for generating productive, decent jobs in this decade.

Generating near full employment in any economy with a high annual increment to the labour force, is a proposition that will require a massive political will to redirect public and private investments towards sectors that generate employment. All this requires deep thinking and this paper merely makes a beginning. All sectors are not the same as far as employment creation is concerned. Some sectors create much more employment, with a given level of investment, than others.The sectors of employment opportunity are:

- Regeneration of degraded natural resources – jal, jangal, Jameen – water, forests and land.

- Diversified agriculture and local value addition in sorting, grading, washing/drying, and packing of agricultural output, including vegetables, fruits, milk, poultry, fish and meat.

- Manufacturing in micro and small enterprises in clusters and small towns.

- Construction sector, particularly lower income housing and lower-end infrastructure.

- Services – digital such as telecom, entertainment and financial services; and “green” services such as solid waste management, operation and maintenance of renewable energy, eco-tourism, health promotion and continuing education.

Regeneration of Degraded Natural Resources

Let us look at the various economic sectors first. Agriculture is the biggest employer but millions of workers and farmers are getting out of it due to low and uncertain earnings.Yet it is possible to stem this tide if investments are made in regenerating the degraded natural resource base for agriculture – water, forests and land – or Jal, Jangal, Jameen. Degraded natural resources include streams, rivers, water bodies, and groundwater aquifers; forests which have been thinned down due to felling and grazing; and cultivated lands whose soils have deteriorated due to excessive chemical fertilizers, over-irrigation or soil erosion.

According to an estimate by TERI, land degradation through various processes in India cost around 2.5 per cent of the country’s GDP in 2014-15. (TERI, 2018) The study estimated total investment required for reclamation of land degraded by five major processes namely water erosion, wind erosion, forest degradation, water logging and salinity. The study found that India requires Rs. 2948 billion or nearly Rs 3 trillion (2014-15 prices) to reclaim 94.53 million hectare degraded land as per latest survey by SAC,Ahmadabad. Assuming an increase in costs since then, India needs to spend Rs 4 trillion, or about 2 percent of the GDP to address the regeneration of degraded land resources.There are millions of jobs possible in regeneration of degraded natural resources, and thereby creating the potential for long-term employment through their sustainable use. This will generate 100 days of work for about 5 crore people each year for three years.As a result of improvements in land and water availability, about one crore people would additionally be engaged in agriculture, dairy, forestry, fishery, etc. more sustainably.

What is notable is that a large number of these jobs are in rural and forested tribal areas, and on the peripheries of urban areas, precisely the locations where jobs are needed. Moreover, 90 per cent of these jobs are unskilled or semi-skilled, which enables the large number of persons in the labour force in those skill categories to get some work in the next few years. Further, there is scope for more than proportionate participation by women in these jobs.

Diversified Agriculture and Local Value Addition

Diversification of agriculture is needed, away from rice, wheat and sugarcane. The demand patterns from consumers are also changing beyond the staple of wheat and rice. Agricultural output needs to be increased in nutrition cereals, oilseeds, pulses, vegetables, fruits, milk, poultry, fish and meat. Most of these generate more employment per hectare as compared to wheat and rice.

Further, it is not enough to merely produce a diverse set of agricultural commodities. As long as farmers merely sell these raw, they will never get an adequate share of the value that these commodities – vegetables, fruits, milk, poultry, meat, etc. create. To capture an additional share of the value added, agricultural workers, particularly women must be engaged in local, pre-dispatch sorting, grading, washing/drying, and packing of the diverse agricultural produce. This will improve the prices received by farmers as well as generate local jobs.

Construction Sector for Lower Income Housing and Infrastructure

In the construction sector, there are large number of jobs possible in the housing as well infrastructure. With a significant shortage of over 20 million dwelling units and the need to upgrade existing housing stock, coupled with the availability of housing finance from banks and housing finance companies, this sector needs a policy and not a fiscal boost. Further, with a need to create and improve the infrastructure in the next 1000 cities, after the current top 100 cities, there will be heavy demand for labour for the creation of infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and public buildings such as schools, health care centres, police thanas, and hospitals.

Nearly 90 per cent of the workforce employed in the real estate and construction sector are engaged in construction of buildings, while the rest 10 per cent workforce is involved in building completion, finishing, electrical, plumbing, other installation services, demolition and site preparation. Over 80 per cent of the employment in real estate and construction constitutes minimally skilled workforce, while skilled workforce account 10 per cent. This matches well with the low skill levels available in the labour force till they get skilled in the next few years.

Manufacturing in Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) in Small Town Clusters

In the non-agricultural sectors, employment has not grown anywhere in proportion to the demand for jobs. Employment growth in the manufacturing sector has remained low, and indeed there are prospects of further slowdown as automation takes off even more broadly. Still, in manufacturing, new jobs will get created in agro-processing around agriculturally productive regions (such as the Doaba region of Punjab, Malwa region of Madhya Pradesh and the coastal belt of Andhra Pradesh; and in niche micro-enterprises in rural areas (such as handloom and handicrafts).

As per Cluster Observatory, a project of the Foundation for MSME Clusters, more than 5600 clusters are operating in India across different product/service categories ranging from automobiles to rural tourism. Manufacturing jobs can grow in these cluster towns (like Moradabad for brass work and Tirupur for hosiery) if the SMEs here are made more productive and export-oriented. New jobs can also be created by establishing new medium and even large industry clusters based on localization of imported products (such as has already happened for mobile phone manufacturing around Chennai and NOIDA).

Small Scale Services – Digital and Green

In services, much of the high-end employment growth was driven in the previous decade by the Information Technology (IT) and IT-enabled services sector. Thus, once again, in services, we will have to look for job growth in digital service sectors like call centres, data centres, telecom, entertainment and finance.

Examples of green services include soil and water conservation, solid waste management, operation and maintenance of renewable energy and eco-tourism. There are many jobs possible in tourism which is a composite services sector. New jobs can be created by developing newer destinations for rural and small-town tourism to religious places as well as eco-tourism to locations with natural beauty or historical significance. Other green services include physical training, personal grooming, and health promotion.

Of course, the older physical services such as retail and wholesale trade, storage and warehousing, transport and hotels and restaurants and business, real estate and personal services will continue to be major employment sources.

Most of these services are offered in the private sector and the state only has to make facilitative policies under the rubric of “ease of doing business”, but ensure that these benefit the large number of micro and small enterprises too. For example, the application of GST, including the requirement of filing returns on-line, is onerous to millions of micro-enterprises and should be applied with a gradual approach, so that the revenue goals are met from the larger enterprises.

Financing Job Growth Using a Multiplicity of Sources

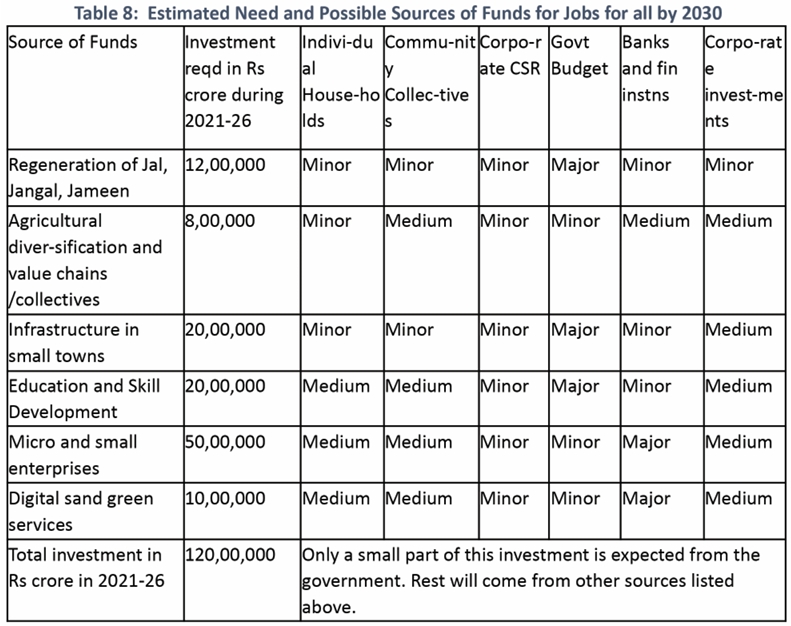

How Much Invest is needed?

The total investment is estimated to be Rs 120 lakh crore (trillion), or about 60 percent of India’s GDP in 2021. This investment would have to be concentrated in the first six years of the decade, to show results by the end of the ten year period. Thus the investment in jobs for all needs only about 10 percent of GDP per annum or about a third of the current annual investment in the economy, for the first six years. All these are summarized below in Table 8:

Source: Author’s computations based on aspirational targets for 12 crore new “decent” jobs by 2030

Sources of Finance Other than the Government

We argue that these sectors should be prioritized for overall investment – both public and private. Private investment will follow the logic of maximizing expected returns, and can only nudged by incentives to sectors that generate high employment. Public investment can, however, be prioritized in those sectors that generate high employment and also create public goods or positive externalities.This needs to be supplemented by private investment, which can be channelized into these areas by suitable incentives and creation of institutional frameworks which provide an assurance of returns to the investment.

This was done five decades earlier for attracting private investment in the industrial sector and two decades ago for attracting private investment in the infrastructure sector. That process will have now to be repeated for the natural resources sector and for the social services sector as well. Some beginnings have already been made in this direction and process needs to accelerated, with safeguards of public interest.

The financing of agricultural diversification will have to be done by farmer households, and through bank loans. Financing of farmer owned agricultural value chains will have to be done by farmer households, community collectives like FPOs, bank loans as well as and corporate finance. Financing of the creation of small infrastructure in small towns and district headquarters will have to be done by the government budget resources and possibly agencies like NABARD RIDF. The financing of non-farm micro enterprises for self-employment will largely have to be done from personal and community resources and through bank loans of the PM Mudra Yojana and Microfinance. So far many of the MUDRA and microfinance loans have gone to “involuntary” entrepreneurs, who are not best users of this.

As Bahety and Ngoma (2022) suggest “microfinance may not be a panacea and that relaxation of both labor market frictions and credit market constraints are necessary to reduce allocative inefficiencies of resources…Public works programs, adult education, skills or vocational training…are some of the key labor market policies to help individuals choose their preferred occupation and increase entrepreneurial productivity and returns.” Public works, adult suction and skill training are needed but cannot be financed by bank loans or microcredit. The financing of regeneration of natural resources will have to be done by the government budget resources and possibly agencies like NABARD, as discussed above.

Conclusion

In summary, to generate 12 crore new “decent” jobs for India in the 2021-30, we are proposing significant investment in major employment generating sectors, and within those, initially on sectors which will generate the demand for a large number of unskilled and semiskilled jobs.

In terms of target segments of the population, the growth in jobs should be higher for women and youth. In terms of spatial allocation, we are suggesting a significant investment in building the infrastructure and economic attractiveness of about 1000 district and cluster small towns, as the next rung of growth magnets, as a countermagnet to the 100 so-called Smart Cities.

As can be seen, the largest number of jobs are for the unskilled but the growth of semi-skilled and skilled jobs has been significantly enhanced, which will also improve wages for workers. For investments in growth to fructify into a large number of jobs with decent wages and working conditions, policies will have to be made more favourable to labour while ensuring institutions work effectively.

The challenge looks daunting, but we have no choice but to modify our policies so that we get not just GDP growth, on which everybody agrees, but that growth be equitable, generating a large number of decent jobs. Further, neither the growth not the employment imperative should make us encourage production of crops, goods and services which are destructive to the environment. Sustainability, along with Jobful growth, has to be triple mantra for this decade.

References and Endnotes

- Bahety, Girija and Marina Ngoma (2022): Microfinance, Microentrepreneurship and Misallocation, In Bahety (2022). Technology Adoption and Welfare Impacts in Developing Countries, Unpublished PhD Dissertation,Tufts University.

- Climate Scorecard https://www.climatescorecard.org/ for GHG emissions data

- International Monetary Fund DataMapper,World Economic Outlook 2021. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPSH@WEO/IND,

- Mahajan, Vijay, Prasanth Regy and Jagmeet Singh (2018). Jobful Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Contemporary Studies, New Delhi

- Karaivanov, and Yindok (2022), Involuntary entrepreneurship – Evidence from Thai urban data, In World Development, Elsevier, 149(C). https://ideas.repec.org/a/eee/wdevel/v149y2022ics0305750x21003211.html

- Mehrotra, Santosh and Sharmistha Sinha (2017). “Explaining Falling Female Employment during a High Growth Period”. In: Economic and Political Weekly 39, pp. 54–62.

- Miron D, McClelland DC. (1979).The Impact of Achievement Motivation Training on Small Businesses. California Management Review. 1979;21(4):13-28. doi:10.2307/41164830

- MoSPI (2021). National Accounts Statistics 2021 NSSO (2019): Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) (June 2017 – June 2021) URL: http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/ publication_reports/Annual%20Report%2C%20PLFS%202017-18_31052019.pdf

Footnote:

- The term “decent work” was first used by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang–en/index.htm and adopted by the UN in 2015