India needs jobs—and HWEs and αHWEs are the key 1

India’s unincorporated sector employs over 90% of the non-farm labour force, making it a critical engine of economic growth. Entrepreneurs in India’s unincorporated sector broadly fall into three categories, differentiated by their scale, ambition, and economic impact:

2.1.1 Own Account Enterprises (OAEs)

Share: Approximately 86% (6.34 crore out of total 7.34 crore) of enterprises. Employing 66% of workers (7.65 crore out of 12.06 crore workers).

Scale & Scope:

Employ 1–2 individuals, generally the entrepreneur and family member. Typical investment: below ₹2.5 lakh.

Annual revenue around ₹2.5 lakh per annum.

Activities & Market:

Focused on hyper-local markets at village or panchayat level.

Undertake basic value-added activities such as pre-processing, trading, or retail.

Finance Needs:

Adequately served by existing microfinance and SHG ecosystems.

Hired Worker Enterprises (HWEs)

Share:

Approximately 13% (1.00 crore out of total 7.34 crore) of enterprises. Employing 34% of workers (4.41 crore out of 12.06 crore workers).

Scale & Scope:

Employ around 4–5 workers. Require investments of ₹5–25 lakh.

Generate annual revenues around ₹18 lakh per annum.

Activities & Market:

Operate at block-level markets and cater to external markets.

Engage in medium-level value-added activities like primary processing (sorting, grading, packaging), distribution, and localized aggregation.

Finance Needs:

Require flexible financing options for fixed capital. Need traditional debt for working capital.

Extraordinary Aspiration HWEs (αHWEs) Share:

Approximately 1% (about 7.5 lakh out of 7.34 crore) of enterprises.

Employing about 12.4% (about 1.5 crore out of 12.06 crore workers).

Scale & Scope:

Employ over 20 individuals on an average (range 10 -100). Require investment of ₹1 crore or more.

Achieve annual revenues ₹ 2-5 crore.

Activities & Market:

Serve district, state, or regional markets, including metropolitan areas.

Perform higher-order value-added activities such as secondary processing, branding, and large-scale aggregation or distribution.

Finance Needs:

Require micro-equity financing for fixed capital.

Require customized, cashflow-linked loans for working capital.

Economic impact: Multiplier and network effects

αHWEs and HWEs function as critical drivers of local and regional economies. αHWEs, akin to “micro- unicorns,” act as regional anchors or super-aggregators, creating substantial market demand. This demand trickles down, providing markets to multiple HWEs, who in turn provide markets to even larger number of OAEs.

Thus, a powerful multiplier effect emerges from αHWEs, setting off a dynamic circulation of goods, services, and capital within the community network.

Additionally, the agglomeration of αHWEs, HWEs, and OAEs generates significant network effects. Each enterprise segment benefits from mutual interactions: αHWEs offer foundational incubation support, finance, and ready markets to HWEs, while HWEs assure steady supply chains for αHWEs.

Similarly, HWEs and OAEs share a comparable symbiotic relationship. This creates an ecosystem where the strength of the network is greater than the sum of its individual enterprises, thereby incentivizing everyone to join and stay within the network.

Policy gap and imperative to shift focus

Despite their high potential for driving regional growth, αHWEs — and to some extent HWEs — have remained largely overlooked by policymakers, mainly due to their smaller numbers and systemic incubation and financing bottlenecks that prevent them from thriving. Consequently, policy efforts stay heavily focused on OAEs, leaving αHWEs and HWEs to navigate challenges on their own.

The need of the hour is to shift policy, efforts, and resources earnestly and dedicatedly toward αHWEs and HWEs if India is to achieve an extraordinary increase in employment.

The key to enabling this crucial shift lies in redirecting the country’s credit DPI toward αHWEs and HWEs — specifically toward what they need to thrive: flexible financing and micro-equity financing.

India’s current DPI for credit

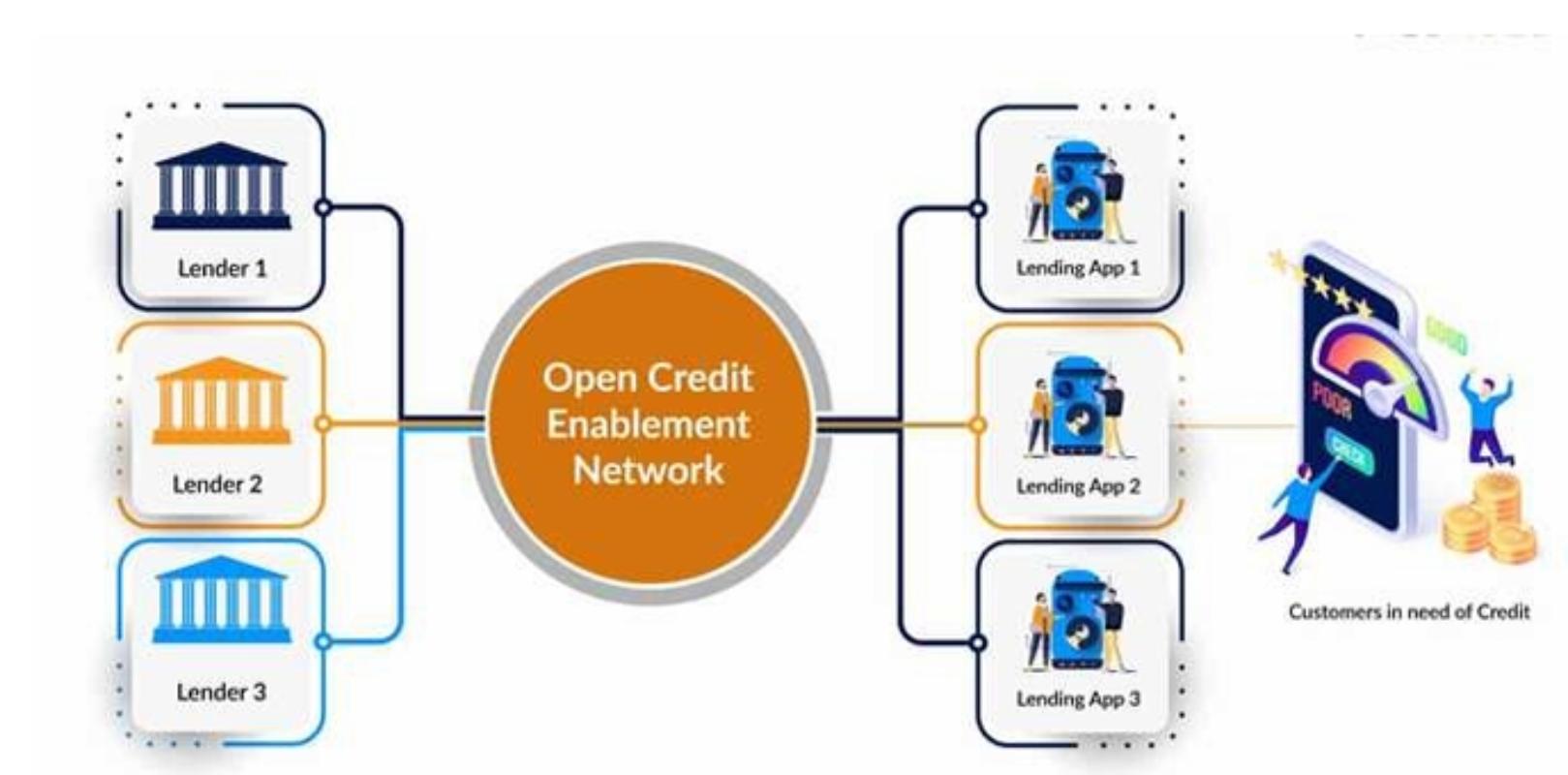

India’s Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) began with the UIDAI and Aadhaar cards, followed by the Unified Payments Interface (UPI). The DPI for Credit—comprising the Unified Lending Interface (ULI), the Open Credit Enablement Network (OCEN)—is a more recent development. It holds the promise of revolutionizing access to finance, particularly for India’s large base of micro-enterprises, estimated at 7.34 crore as per ASUSE 2023–24.

So far, however, the focus has been primarily on enabling instant, small-ticket, short-duration loans tailored for nano enterprises—the OAEs2. Within this framework, OCEN enables interoperable loan offers, while ULI facilitates rapid documentation and onboarding.3

Current system prioritizes OAEs and offers inflexible loan products

Both ULI and OCEN remain optimized for rigid, EMI-based products such as invoice financing4 and Pradhan Mantri Mudra Yojana (PMMY) loans, which address only a part of the financial needs of nano enterprises (OAEs).

As evidence, the average loan size under PMMY between 2016 and 2025 has been ₹55,623. Even more telling is that 83.4% of all PMMY loans have gone to the below-₹50,000 Shishu category, where the average loan size was ₹27,057.

Only 2.0% of the loans have been extended to the Kishore category (typically representing hired worker enterprises), with an average disbursed loan size of ₹654,509. It is important to note that this figure reflects the disbursement value; during the lifetime of the loan, the average outstanding amount tends to be about half of the disbursed amount.

While focusing on OAEs has helped advance financial inclusion for enterprises at the base of the pyramid, it has also overlooked the much bigger credit challenge faced by India’s most transformative businesses — HWEs and αHWEs. These growth-oriented businesses require need-based, larger-ticket financing (₹5–25 lakh) for longer durations (3–5 years), structured around their cashflow variability and performance-linked repayment capacity. What they need is not instant microcredit, but larger, flexible finance and micro-equity solutions—needs that current DPI flows do not yet adequately support.

True potential lies in serving growth-oriented HWEs and αHWEs

Ironically, while current DPI use cases cater largely to OAEs—who often lack digital records, operate informally, and show limited repayment capacity—DPI is structurally better suited for HWEs and αHWEs. These enterprises, although underserved by traditional finance due to perceived risks like revenue seasonality and informal nature of business, are relatively more digitally active5and can generate the kinds of transaction data (via GST, UPI, ONDC, AA) that DPI is designed to leverage.

How must credit DPI be designed to serve HWEs and αHWEs

The Credit DPI is still relatively new and can be designed to serve more promising segments—both in terms of growth and employment potential—of the Indian enterprise sector: the HWEs and αHWEs. The upcoming credit DPI frameworks, such as ULI and OCEN, must treat HWEs and αHWEs as priority, given their economic multiplier effect and digital readiness.

ULI and OCEN must introduce flexible finance and micro-equity

The upcoming credit DPI platforms must evolve rapidly to support new loan product templates that reflect the diverse capital needs and repayment realities of these enterprises. Key features should include:

Demand-based financing: Larger loans with longer tenures (e.g., ₹5-25 lakh for 3–5 years). Flexible Financing with Repayments Linked to Cashflows (FFRC):

Revenue-based financing (e.g., 5% of monthly gross sales), Profit-sharing structures (e.g., 20% of monthly profit),

Dynamic tenure loans (e.g., repayment until a target multiple is reached),

Deferred-start loans with ballooning repayments (e.g., “repayment begins after monthly sales cross

₹X”—ideal for seasonally ramping businesses).

Micro-equity or equity-like participatory capital:

Equity-style investments such as ₹15-25 lakh for a five-year term,

Innovative instruments like micro-convertibles or SAFE6 notes that align financier returns with enterprise performance without diluting ownership prematurely.

Leverage GSTN and ONDC data for offering flexible finance and micro-equity

The transactional data from the GST Network (like e-way bills and GST invoices) and ONDC shouldn’t just be used to support commerce — it should also power a data-driven embedded finance layer. This layer can offer flexible finance and micro-equity products, especially for HWEs and αHWEs who trade actively on these platforms. Loan or equity offers can be triggered automatically at the time of each transaction, based on real- time business activity. Key enablers can include:

Access to flexible finance through the seller dashboard, based on real-time performance.

Use of live transaction data for cashflow-based underwriting7. Pre-approved, flexible financial products offered through seamless integration with OCEN and AA.

For example, if a seller receives a big order, the platform can immediately offer them a loan to help fulfil it. Once the seller delivers the order and earns money, a small part of that payment can be automatically deducted to repay the loan.

This way, sellers get the support they need exactly when they need it, without any paperwork or stress about separate repayments.

Transform the Account Aggregator (AA) into an intelligent risk infrastructure

The AA framework holds immense potential to address a persistent barrier in MSME financing: the inability to assess creditworthiness beyond traditional financial records.

While AA currently facilitates access to structured data—such as bank transactions, GST returns, and UPI

trails—8 its value remains underutilized for high-growth enterprises like HWEs and αHWEs.

These enterprises often remain excluded from formal credit due to the non-linear nature of their financial behaviour, including:

Seasonal and volatile revenues, especially during startup and scale-up phases.

Irregular but responsible repayment patterns that do not align with rigid credit bureau norms such as “Days Past Due (DPD).”

To address this, AA must evolve from a passive data pipe to an intelligent, AI-powered risk infrastructure— capable of building a real-time, multidimensional profile of enterprise viability and enabling performance-linked finance.

Additional features needed for a Robust Credit DPI

Beyond enabling ULI and OCEN to offer Flexible Finance and Micro-Equity products and using GSTN and ONDC data to support these offerings, the Account Aggregator (AA) system must also be upgraded into an Intelligent Risk Infrastructure. In addition, several completely new features will need to be added to strengthen the Credit DPI.

Capture a holistic enterprise dataset

To reflect the true viability of HWEs and αHWEs, AA integrations must go beyond current data sources to include:

Comprehensive Business Cashflows: Including geolocation-based market demand, asset base (machinery, inventory, real estate), recurring operational costs (utilities, rent, marketing), and labour payments—critical for assessing unit economics and working capital dynamics.

Expanded Repayment Histories: Captured not just via traditional credit bureaus but from digital sources such as accounting platforms, e-commerce marketplaces, NBFCs, and micro-lenders.

Psychometric Indicators: Digitally assessed traits such as aspiration, self-efficacy, risk appetite, and perseverance—highly predictive of entrepreneurial success in informal markets.

Alternative Data Streams: POS usage, RFID scans, wallet app activity, and even CCTV-based footfall analytics—already used in consumer fintech—can offer real-time insight into business performance.

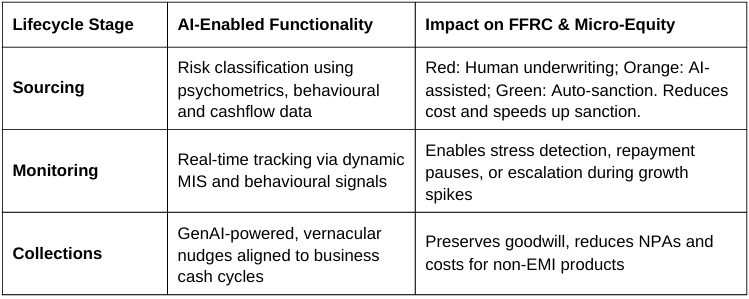

Use AI to automate the enterprise credit lifecycle

To make FFRC and Micro-Equity viable at scale, India’s DPI stack must support dynamic, AI-based credit intelligence throughout the lending lifecycle:

Strategic Value Propositions:

Manual management of FFRC and micro-equity is impractical at scale. Embedded AI agents can make flexible models operationally viable for mass-market lenders.

Automated sourcing, monitoring, and collections reduce the cost-to-serve—crucial for offering flexible financing products for sub-₹10 lakh loan sizes.

Predictive scoring based on alternative and behavioural data unlocks credit for entrepreneurs who were previously considered ‘unlendable’ or had ‘impaired credit bureau’ records but are now ready for growth.

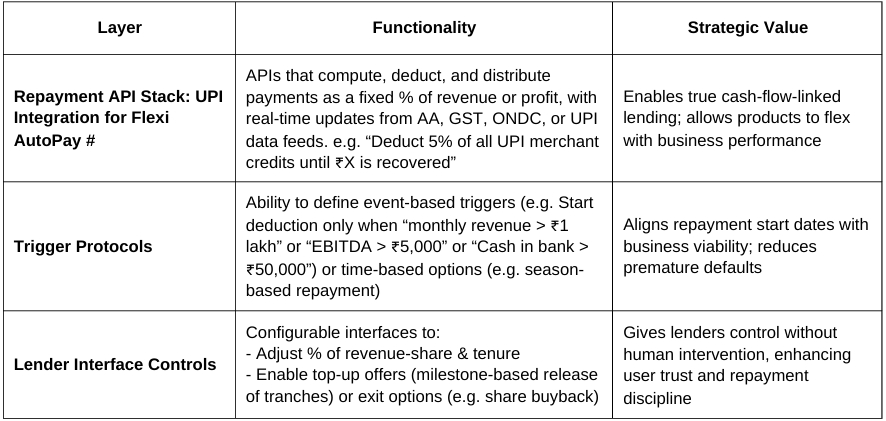

Transform UPI into an Automated Flexible Repayment Infrastructure

A defining feature of flexible finance isn’t just how credit is assessed — it’s how it’s recovered. To operationalize revenue-share, profit-linked, and deferred repayment models at scale, India must establish a standardized, API-based repayment infrastructure within its DPI.

Currently, all repayment rails—eNACH, UPI Autopay, standing instructions—are optimized for fixed EMIs. They are ill-suited to handle dynamic or performance-linked obligations. This bottleneck threatens the viability of non-EMI credit models such as FFRC and Micro-Equity.

Therefore, DPI must support a programmable repayment architecture that is plug-and-play for lenders and seamless for borrowers.

Core components of the repayment architecture

# A promising implementation pathway for flexible finance can be automated revenue-share repayment, directly linked to the merchant’s sales. For instance, repayments can be auto-deducted via a UPI merchant QR code tied to a special account,9 with a fixed percentage of each sale—whether online or offline— channelled to the lender. This ensures that repayments are fully aligned with business cash flows: when sales dip, repayments decline; when sales surge, the loan is paid off faster.

While UPI 2.0 and e-mandates already make this technically possible, what’s still missing is a common, open system built into India’s digital public infrastructure.

ULI and OCEN can make this happen by creating a Revenue-Share Loan API, where a simple field like ‘repayment rate’ sets what percentage of sales will be deducted, and connected systems automatically pull live sales data from platforms like Account Aggregator, UPI, GST, or ONDC.

This system can be made even smarter by using automated contracts. For example, if a business’s GST sales are ₹X in a month, the bank can automatically deduct a small percentage (X × repayment rate) from their account using e-NACH. This kind of fully automatic repayment setup can first be tested in an RBIH sandbox, where important results like default rates, recovery costs, and how much money is recovered for every ₹ of sales are carefully tracked. Once it’s standardized within India’s digital public infrastructure (DPI), revenue-based lending will become plug-and-play — making it much easier for high-growth MSMEs to access flexible capital at scale.

Call to Action

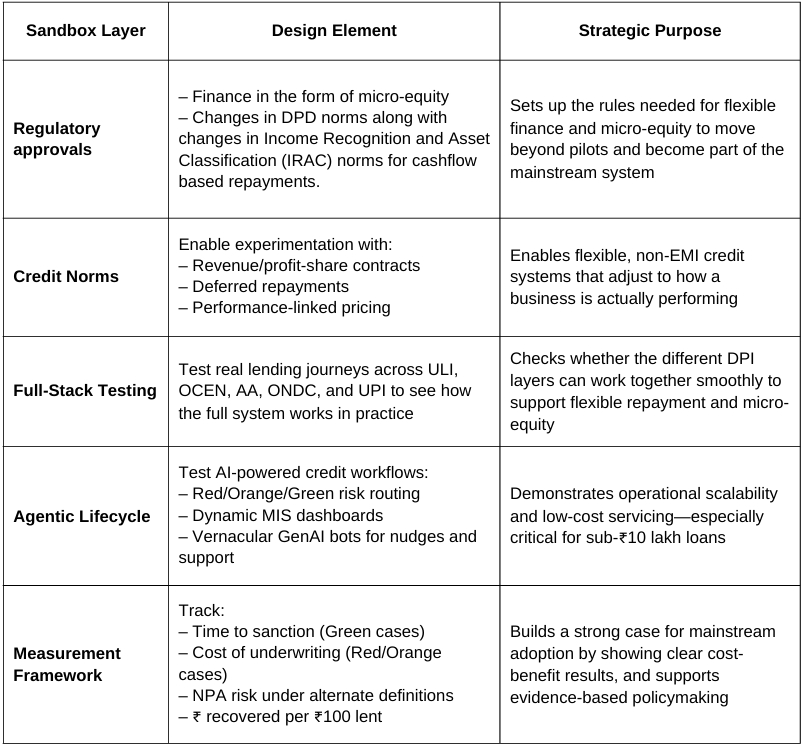

Launch RBIH-Led, OCEN-Enabled sandbox pilots

To make Flexible Finance and Micro-Equity a permanent part of the system for HWEs and αHWEs — the Reserve Bank Innovation Hub (RBIH) must lead a new wave of sandbox pilots focused specifically on these models. Earlier sandbox pilots mainly tested digital delivery of traditional loans. Now, it’s critical to test products built for non-linear growth, unpredictable cashflows, and performance-linked repayments — all key features of HWEs and αHWEs.

As the tech backbone of India’s public credit infrastructure (e.g., ULI), RBIH is uniquely positioned to design and oversee such innovation cohorts. These pilots should span key sectors like agri-processing (across primary to tertiary levels), non-farm manufacturing, and handcrafted industries (handlooms, powerlooms, artisan clusters). Importantly, pilots should target two enterprise life stages:

- Startup and high-growth phase (post product-market fit, pre-breakeven),

- Moderate-growth phase (EBITDA-positive or post-breakeven).

Key Design Features of the Proposed RBIH Sandbox

From Proof-of-Concept to systemic scale

Once the model is validated, RBIH ca9n recommend formal upgrades to DPI protocols like ULI and OCEN to natively support flexible repayment flows and equity-like instruments. This would pave the way for RBI to officially approve revenue-based financing pilots, with the right borrower protection safeguards in place.

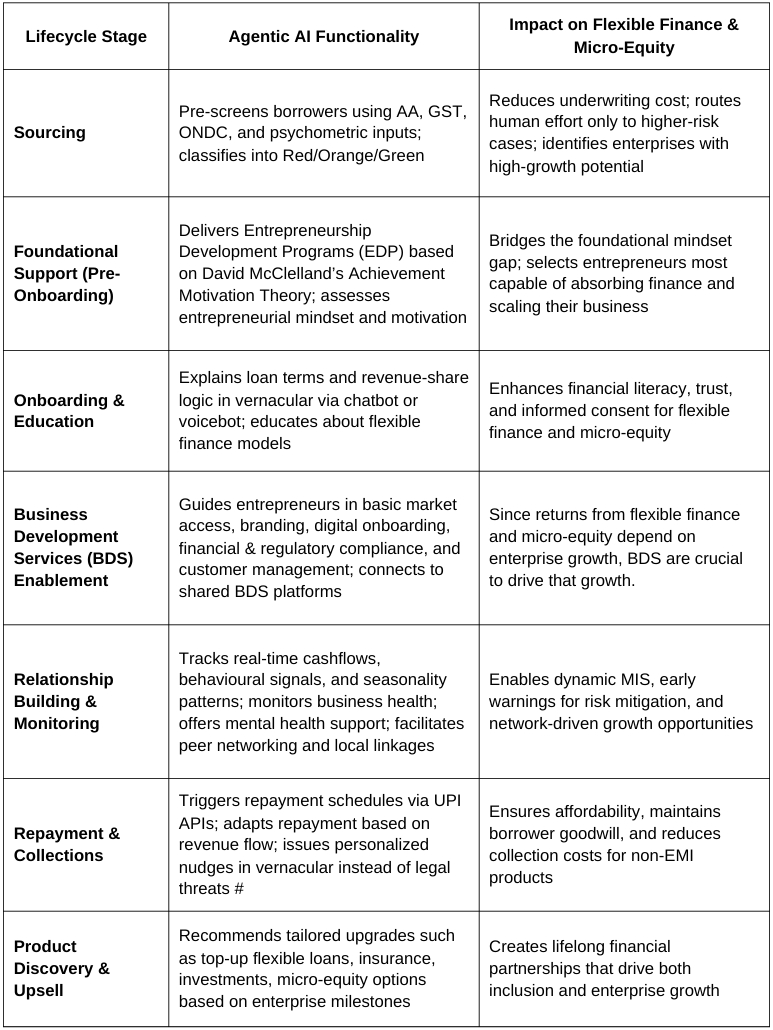

RBIH and OCEN to Co-develop an agentic AI layer for enterprise financing

To scale flexible finance for India’s most dynamic but underserved enterprises—HWEs and αHWEs—India needs more than robust data rails and upgraded credit protocols. It needs a national Agentic10 AI layer: an always-on, multilingual, low-cost virtual advisor embedded across the credit DPI stack (ULI, OCEN, AA, ONDC).

This Agentic AI won’t just be an automation tool — it will serve as a full-lifecycle finance and incubation partner, acting like a virtual loan officer, business coach, personal growth guide, and BDS provider for millions of first-generation and growth-stage entrepreneurs.

Core Agentic AI Functions Across the Enterprise Lifecycle

# For example, instead of sending a legal notice after a delay, AI could simply ask: ‘How is your business doing this month? Would you like a grace period?’ If the borrower agrees, the system could automatically adjust the repayment timeline — preserving trust and reducing the risk of default. Over time, this builds ‘relationship equity,’ which becomes as valuable as credit history for long-term financial inclusion.

Strategic value for India’s DPI

Massive Cost Efficiency: Enables the credit DPI to manage ₹10–25 lakh flexible finance at minimal per- user cost—impossible under manual models.

Possibility of Re-Inclusion: Onboards MSMEs excluded due to damaged credit scores1,1using behavioural and alternative data for eligibility assessment.

Adaptive Product Innovation: Real-time AI feedback sharpens credit product design, helping DPI refine FFRC and micro-equity offerings as the market evolves.

Trust-Led Digital Interface: Builds a human-like relationship between entrepreneurs and the financial system—without dependence on physical bank branches.

To operationalize this system, the RBIH may take the lead to develop a national open-source Agentic AI toolkit hosted within the ULI/OCEN sandbox layer under the credit DPI governance. It may have LLM APIs, multilingual plug-and-play integrations for banks and NBFCs and embedded compliance checks to ensure transparent AI operations.

Policy leadership by the Ministry of Finance and the Reserve Bank of India

India is doing well on economic growth, but employment remains a concern, along with the broader challenge of ensuring inclusive growth. The MSME sector represents the next great hope for employment generation— but within it, it is not the 6.34 crore OAEs that will drive job creation.

It is the 1.0 crore HWEs that, given adequate access to finance for startup, growth, and navigating occasional shocks, can generate crores of new jobs. However, the present banking sector must significantly change its approach to enterprise lending.

As we have stated earlier, the level of transformation required—in policies, products, and processes—is similar to the shift that transformed old-generation IRDP poverty alleviation loans, which had repayment rates of only 18–20%, into the new-generation Self-Help Group (SHG) lending model, where repayment norms of 95–99% became the standard.

Achieving this level of transformation requires strong policy leadership, a task worthy of the Ministry of Finance and the Reserve Bank of India.

The encouraging fact is that both the demand and the building blocks for breakthrough solutions already exist. New credit worth ₹15–20 lakh crore and potentially over 10 crore new jobs can be unlocked through decisive policy action.

1 Quantitative data on enterprise distribution, employment, investment, and annual revenue is sourced from the Annual Survey of Unincorporated Sector Enterprises in India (ASUSE 2023–24), conducted by the NSSO, GoI. https://mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/publication_reports/ASUSE_2023_24_Full_Report-L.pdf. Qualitative insights on enterprise activities and market behavior are based on the authors’ field-level experience across multiple states. Insights regarding the financing needs of different enterprise segments are derived from the policy paper: Mahajan, Vijay and Bhargava, Pranay, “SME Financing – How to Bridge the Persistent Demand Supply Gap?” (February 17, 2025), available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5141173 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5141173.

2 Initiatives like PM SVANidhi, GST Sahay, and PSB Loans in 59 Minutes serve OAEs (e.g., street vendors, sole proprietors). UPI, GSTN, and AA integrations are being used primarily for small-ticket lending pilots through fintechs focused on nano and micro enterprises.

3 ULI is still in prototype/pilot stage and is being tested for high-frequency, low-ticket lending scenarios (e.g., small traders, retailers, nano enterprises).

4 OCEN 1.0 templates support standard EMI-linked products (e.g., short-tenure working capital loans, invoice discounting).

5 As per ASUSE 2023-24, HWEs show higher formalization (47.8% licensed, 23.4% registered), better digital adoption (24.3% computer use, 58.5% internet access), and financial practices (5.7% maintain audited accounts).

6 This may involve providing capital upfront in exchange for the right to receive equity at a future valuation event. This allows investor to participate in potential upside without requiring immediate valuation negotiations or complex structuring, making it particularly suitable for micro enterprises where conventional equity deals may be premature or burdensome.

7 ONDC logs structured sales metadata—such as volume, frequency, price, and fulfilment—which can be leveraged for cashflow modelling. These transaction trails, when combined with data from the Account Aggregator and GSTN, can enable robust, DPI- aligned credit scoring.

8 As of March 2025, AA networks allow consent-based sharing of data from banks, NBFCs, GSTN, TSPs, and some investment and insurance repositories. It’s live through the Sahamati ecosystem and being scaled by banks, fintechs, and NBFCs.

9 While UPI 2.0 supports e-mandates and recurring debit instructions—allowing lenders to collect fixed or pre-agreed payments from merchants, with mandates tied to specific accounts and set to recur (e.g., daily, weekly)—UPI APIs do not yet support native revenue- share logic, such as repayment_rate fields or dynamic deductions based on a percentage of sales.

10 Agentic AI is a type of artificial intelligence that focuses on autonomous systems capable of making decisions and performing tasks independently, without human intervention. These systems can analyze data, set goals, and take actions, often adapting to changing environments and learning through experience. https://www.uipath.com/ai/agentic-ai

11 Damaged credit bureau scores in rural areas represent a significant challenge in India. Defaults under SHG-bank linkage programs or JLG microfinance—often caused by circumstances beyond the borrower’s control or unforeseen contingencies—frequently lead to impaired credit histories. While comprehensive national statistics are lacking, the author’s field-level experience across multiple Indian states suggests that nearly one-third of applications from HWE entrepreneurs are rejected by banks and financial institutions due to past credit score damage.