As we write, the Taliban forces enter Kandahar, the second largest city of Afghanistan, thereby consolidating Taliban control over 85 percent of the country, even as the US is determined to withdraw its forces by the end of August after a two decade presence. Under such circumstances, to say Afghanistan is in turmoil doesn’t say much.What is of greater relevance is the prognosis for the future of Afghanistan and based on that, the appropriate changes required in India- Afghanistan relations, at least in the short and medium term.

The Dilemma for India

The following piece by Shekhar Gupta aptly summarises the two sides of the argument:

Excerpts from Episode 406 of #CutTheClutter where Shekhar Gupta,The Print, 5 March, 2020 `

Five reasons why many justify India’s involvement in Afghanistan:

- Afghanistan is of great strategic importance and can’t be left with a power

- From the British, Soviet Union, to America, there has always been a foreign power to stabilise Additionally, it is believed that after the British empire, the burden now falls on India to manage the region.

- Afghanistan offers an important transit route that connects energy in Central Asia and commerce in

- Afghanistan is the resource-rich region with lots of minerals that India has great commercial interests

- India cannot cede Afghanistan to

Why India should cede Afghanistan to Pakistan

- Afghanistan is of great strategic importance, but for who? Not for Afghanistan and India do not share a border, none of our transit routes go to Afghanistan and no trade goes there.

- Afghanistan is not really a threat to Former national security advisor Shivshankar Menon recently pointed out that in all these years, there has been only one Afghan terrorist who was found in India. Afghanistan has no sanctuaries of terrorists who want to target India.

- There might be a power vacuum in Afghanistan, but have Afghans ever benefitted from the presence of a big power? Furthermore, have big powers benefitted from being there? Afghanistan is a country of minorities, ethnic diversity, with no core population. Power is always to be shared with clans, clan chiefs, tribes, thugs, mercenaries Hence, it is very difficult to run Afghanistan as a unitary centralised country, with a centre of authority.

- Afghanistan is important for transit, but Afghan transit routes are not available to India unless Pakistan allows it. First, we will have to improve relations with Pakistan.At present, Pakistan doesn’t even allow transit of high-protein biscuits for Afghan children. It is also a very difficult topography and terrain to reach Afghanistan by bypassing

- Afghanistan is resource-rich, but India will probably lose out to China in this respect. However, India’s own mineral wealth has been very poorly exploited, with only about 60 per cent of our current resources being tapped So it might not be worthwhile focusing on Afghanistan’s mineral resources.

- India should cede Afghanistan to Pakistan, as Afghanistan is the graveyard of The British, Soviet Union and America have all failed in subduing Afghanistan.The US- Afghan agreement was not a peace deal, but a withdrawal deal and sign of America surrendering from the region.

- Pakistan’s borders with Afghanistan are not The moment there is a proper government in Afghanistan, there will be Afghan nationalism and Pakistan will have a problem. Additionally, Pakistan already has five to six army divisions in the ‘Af-Pak’ area and could add about 10 more. It is better for these Pakistani forces to be in Afghanistan than be facing India.

If we continue fighting Pakistan in Afghanistan, we give moral justification to Pakistan army and ISI to continue in Afghanistan. Hence, India should take a ‘chanakyaneeti’ approach, and stay out of it.

What is at Stake for India?

Apart from historical ties India has with Afghanistan, realpolitik dictates that India’s role in and relationship with Afghanistan is determined by the stake it has in that country. Geography still remains an important factor in contemporary geopolitics. If Mahmood Qureshi, Pakistan’s foreign minister articulates the possibility of Pakistan being hemmed in by India and (a hostile) Afghanistan, there’s greater possibility of ISI moving, after the withdrawal of US and Allied forces, a large chunk of highly trained and battle-hardened Taliban fighters with close ties with the Haqqani group to Kashmir through POK. So, India’s security is at stake.

On the other hand, General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani, the commander-in-chief of the Pakistani army, had famously said in a speech in 2001, “Strategically, we cannot have an Afghan army on our western border which has an Indian mindset and capabilities to take on Pakistan”. Taliban is virtually the creation of Pakistan – as a proxy to control Afghanistan, so that India can be kept away and not encircle Pakistan from the north by Afghanistan and from the south by India.As researcher Christian Wagner notes, in the 1990s, the Pakistani military had linked its Afghanistan relations with the Kashmir conflict.

The former Pakistan President General Pervez Musharraf had said in 2015 that the country’s intelligence agency ISI had “cultivated” the Taliban to counter the Indians. So, when the Taliban were in power, they were seen as the perfect partner for the Pakistani military. Although viewed as medieval by the West, the Taliban regime was valued in Pakistan as fiercely anti- India and therefore deserving Pakistani arms and assistance. Pakistan’s doctrine of “strategic depth” was complemented by its strategy of “asymmetric warfare” — using jihadi fighters for its own ends. Pakistani generals have long viewed the jihadis as a cost-effective and easily- deniable means of controlling events in Afghanistan. The point being made is that Pakistan’s geopolitical agenda casts a long shadow on India-Afghanistan relations.

The fact that China shares a border with Afghanistan is important to note. The Chinese project – the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – could well be extended into Afghanistan. The project is part of Xi’s plans for massive economic heft over other countries besides deepening partnerships in security, trade, and energy that will drive China’s growth story in years to come. Considering China’s heft – and not to forget Afghanistan and China share border – It doesn’t take much imagination to figure out the likely impact a China-Afghanistan strategic cooperation may have on India’s influence on Afghanistan.The Afghan President Ashraf Ghani said in an interview to CNN: “We have a lot of positive relationships with China and the growth of China now is going to be the factor as growth of India for regional prosperity,”

India-Afghanistan Relationship – A Brief History

India’s relations with Afghanistan has been distinctly interlinked with the regime in power. In January 1950, with King Zaheer Shah on the throne, India signed a five-year Treaty of Friendship Afghanistan in New Delhi; following which diplomatic relations were established. Yet when in July 1973, Zaheer Shah was overthrown in a coup by his cousin and Prime Minister, Mohammed Daoud Khan and established Republic of Afghanistan with himself as President and supported by Marxist Leninist party, People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), India not only recognized the new government but signed a trade protocol the next year. This should be seen in the backdrop of the fact India had signed a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation with the Soviet Union in 1971, in the run up to the war with Pakistan later that year, which led to the creation of Bangladesh out of erstwhile East Pakistan.

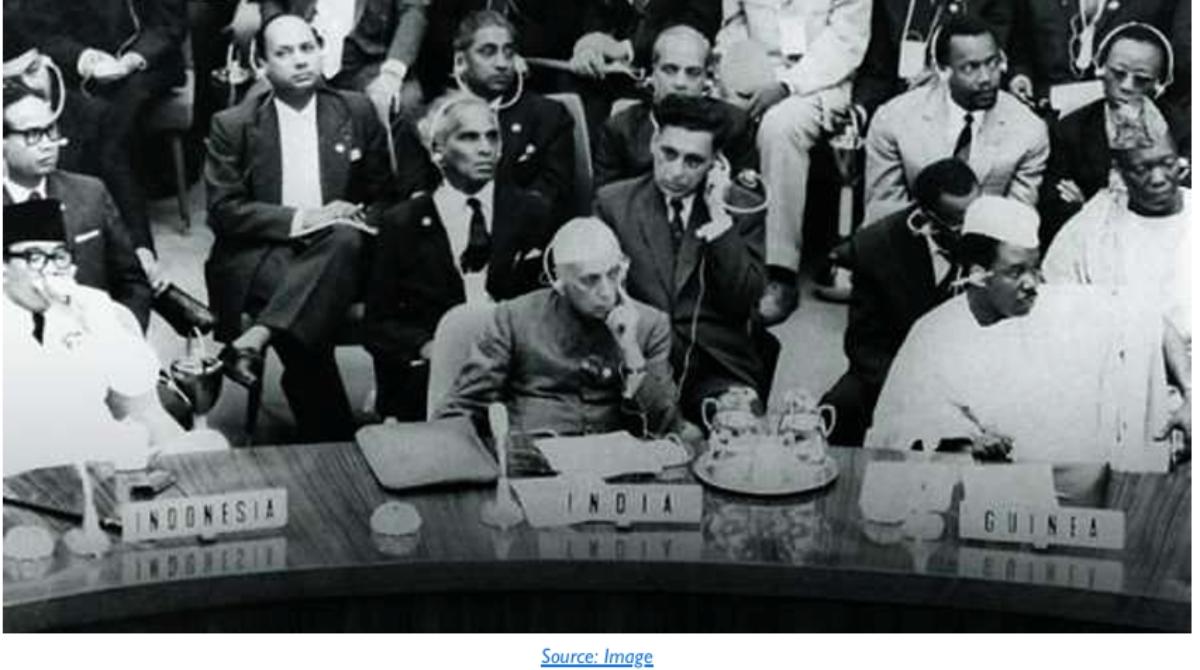

Six years later, when a fractious Marxist government of Babrak Karmal’s was installed after the Soviet invasion of December 1979, India was the only South Asian country to recognize Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. In the same vein, India was only one among four countries that supported the Soviet intervention even as 34 nations of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation adopted a resolution demanding “the immediate, urgent and unconditional withdrawal of Soviet troops” from Afghanistan.

After the withdrawal of Soviets in February 1989, Afghanistan was embroiled in civil war which did not end even with the formation of Islamic State of Afghanistan in 1992 following the Peshawar Accord in which Pakistan played a dominant role. When the Taliban finally conquered Kabul in September 1996 and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan – which was recognized by only three nations: Pakistan, UAE and Saudi Arabia – India’s diplomatic presence in Afghanistan was zero. It was only after the Taliban was driven off following US intervention in 2001 and the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was restored that India re- established relations with Afghanistan. So, for all practical purposes, India had no presence in Afghanistan for eleven years: 1989 to 2001.

Hamid Karzai’s ascension to power shortly after 9/11 provided a golden opportunity to India. Karzai became the head of state of Afghanistan in December 2001 after the Taliban government was overthrown. Karzai was appointed at the 2002 Loya Jirga as the Interim President of the Afghan Transitional Administration. After the 2004 Afghan presidential election, he became the President of Afghanistan. Karzai hated Pakistan with a passion, in part because he believed that the ISI had helped assassinate his father in 1999. At the same time he felt a strong emotional bond with India, where he had gone to university in the Himalayan city of Simla.

So with Karzai in office, India seized the opportunity to increase its political and economic influence in Afghanistan, re-opening its embassy in Kabul, opening four regional consulates, and providing substantial reconstruction assistance totaling around $1.5 billion, with an additional $500 million promised within the next few years. The aid and reconstruction program it set in motion during the 1980s was so generous that it quickly established India as the single largest donor in the country. It was also carefully thought out, praised as one of the best planned and targeted aid efforts by any country. India has built roads linking Afghanistan with Iran so that Afghanistan’s trade can reach the Persian Gulf at the port of Chabahar, thus freeing it of the need to rely on the Pakistani port of Karachi.

On 7th July 2008, there was a car bomb attack on Indian Embassy in Kabul that killed 58 and wounded 141. On 1 August 2008, United States intelligence officials said that the Pakistani intelligence services helped the Haqqani network plan the attack. Then on October 8, 2009, a massive car bomb had been set off outside the Indian embassy in Kabul killing 17 people and wounding 63. Most of the dead were ordinary Afghans caught walking near the target. A few Indian security personnel were wounded, but blast walls built following a much deadlier bombing the previous year which killed 58 and wounded 141—also thought to have been sponsored by Pakistan—deflected the force of the explosion, so that physical damage to the embassy was limited to some of the doors and windows being blown out. In the case of the 2009 attack, American officials went public with details from phone intercepts which they said revealed the involvement of the ISI.

Few months later, on 26 Feb 2010, blasts in two Indian guest houses in Kabul killed 18 people, including 9 Indians. Among them was assistant consul general from the Indian consulate at Kandahar. The operation was soon traced by bothAfghan and U.S.intelligence to a joint mission by the Pakistani-controlled Haqqani network, a Taliban-affiliated insurgent group under the leadership of Jalaluddin Haqqani, and the Pakistan-based anti-Indian militant group Lashkar- e-Taiba, which carried out the November 2008 assault on the Taj Hotel and other targets in Mumbai. Both the Haqqani network and Lashkar-e-Taiba were believed to take orders from the ISI—Inter-Services Intelligence, which is closely linked to the military. Pakistan made no public comment on the attack, other than to refuse permission for the planes carrying the dead bodies back to India to cross its airspace.

Such attacks were a serious setback to India’s efforts to establish a strategic presence in Afghanistan through a wide range of developmental projects. Afghanistan had been a priority area for India’s foreign policy, and for its (then) $1.2-billion development diplomacy in Afghanistan which had earned considerable goodwill from the Afghan population. Soon after the 2009 attack, President Hamid Karzai termed it a “terrorist attack against Indian citizens who are working to help rebuild Afghanistan”. So, following the successive attacks on the Indian Embassy at Kabul, one obvious response was to beef up security considerably, and an elaborate plan was implemented. But Indian doctors and engineers working on different projects around Afghanistan were the ones who were most vulnerable.The second response was to engage in a security pact with the government of Afghanistan.

While such attacks were obviously aimed at destabilizing India’s presence in Afghanistan, India continued to help build electrical power plants, health facilities for children and amputees, 400 buses and 200 minibuses, and a fleet of aircraft for Ariana Afghan Airlines. India has also been involved in constructing power lines, digging wells, running sanitation projects and using solar energy to light up villages, while Indian telecommunications personnel have built digitized telecommunications networks in 11 provinces. One thousand Afghan students a year have been offered scholarships to Indian universities. India has also played a key role in the construction of a new Afghan parliament in Kabul at a cost of $25 million. All this led to India becoming enormously popular in Afghanistan: an ABC/BBC poll in 2009 showed 74% of Afghans viewing India favorably, while only 8% had a positive view of Pakistan.

In February 2010, at the London conference to discuss the future of Afghanistan, most countries including the five permanent members of the UN Security Council (the US, the UK, Russia, China, and France) overwhelmingly supported the policy of talking to the Taliban. This stemmed from the assessment that the US and its NATO allies perceived Afghanistan to be a protracted battle and now wanted to look for quick-fix solutions that would help them exit the country early.

For Delhi, it was bad news, as was the snub which kept them on the margins of the London conference. According to the analysts, India was left with few options. It had no say in the international community’s “good Taliban” strategy and would continue to engage closely with the Hamid Karzai Government and provincial satraps. In addition, it could use back-channels to try and keep communications open with those Taliban elements who shun violence as they could eventually find space in the political mainstream. India was looking to bolster its security personnel as also its current training programme for Afghan officers.

At the time when India’s largest effort– the 218-km Zaranj-Delaram highway was being built, the ITBP had a presence of around 350 personnel. By 2010, the ITBP had a force of 150 troopers guarding the Indian embassy in Kabul and the consulates at Mazar-i-Sharif, Jalalabad, Herat and Kandahar. A review of the security was to be carried out following Menon’s visit. Deploying Indian troops in Afghanistan to safeguard Indian interests had been entirely ruled out. However, a growing consensus was building up within Indian military think tanks for training at least two divisions of the Afghan National Army (ANA).A net assessment presented in February 2010 for the Centre for Joint Warfare Studies (CENJOWS), the think tank for the triservices’ HQ Integrated Defence Staff, called for the capacity building of the ANA: “India could offer to pay for and equip and train up to two Afghan divisions– an artillery and armoured brigade each of the ANA–over and above the sanctioned strength of 1,34,000,” said Major General (Retd.) G.D. Bakshi, who headed the study.

In June, 2010, much to the alarm of India—and the U.S.—Karzai decided to attempt negotiations with the Taliban. In preparation for this, Karzai removed his strongly pro-Indian and deeply anti-Pakistani security chief, Amrulla Saleh, a tough, bright Tajik who had risen to prominence as a protégé of Massoud and was viewed by the Taliban and their backers in the ISI as their fiercest enemy. As Bruce Riedel, then President Barack Obama’s AfPak adviser, said when the news broke: “Karzai’s decision to sack Saleh has worried me more than any other development, because it means that Karzai is already planning for a post-American Afghanistan.”

The head of the ISI, Lt. General Ahmad Shuja Pasha, and General Kayani, the head of the Pakistani army, shuttled between Kabul and Rawalpindi, presumably to encourage some sort of accommodation between Karzai and the ISI-sponsored jihadi network of the Haqqanis that would leave Karzai in power in Kabul in return for a more pro-Pakistani dispensation in the south.There was even talk of Pakistan agreeing to help train the troops of the Afghan national army. In the end, however, the reconciliation lasted less than a year.

Kayani and Karzai soon fell out, and in 2011 the pendulum swung the other way when Indian Prime Minister Manmohan Singh visited Kabul, where he signed a strategic partnership deal promising closer cooperation on national security, this time with an agreement to provide light weapons as well as training in counterinsurgency and high-altitude warfare.

In September 2011, former Afghan president Burhanuddin Rabbani was assassinated. While it is not clear if his assassination was part of the same pattern targeting Indians and Indian interests, next month in October 2011, Afghanistan signed its first strategic pact with India. The military assistance was to include training of Afghan security personnel. But even over here, the Pakistan angle was visible. During his visit to India, Karzai told the media that “This strategic partnership is not directed against any country. This strategic partnership is to support Afghanistan.” He also stated that “Pakistan is our twin brother, India is a great friend. The agreement we signed with our friend will not affect our brother.” He also added that “However, our engagement with Islamabad has unfortunately not yet yielded the result that we want.”

It is therefore not just India that may be said to be obsessively concerned over Pakistan. Karzai’s statement shows that the shadow of Pakistan loomed over Afghanistan as well. To that end, President Karzai signed the Strategic Partnership Agreement during his visit to India in 2011 that formalized a framework for cooperation in the following areas: ‘political & security cooperation; trade & economic cooperation; capacity development and education; and social, cultural, civil society & people-to-people relations’. Most Indian assistance fits into three broad categories: humanitarian assistance, infrastructure projects and capacity building. In the early years, even providing humanitarian aid was difficult because of the intransigence of Pakistan.

For example, the food assistance, in the form of fortified wheat biscuits, was equivalent to around 500,000 tonnes of wheat.The biscuits are processed by the World Food Programme and distributed daily to two million Afghan school children. The wheat shipments were announced in June 2011 but Pakistan prevented wheat transiting through its territory. In March 2012 Pakistan finally allowed 100,000 tonnes of wheat to pass through by road and rail via Karachi. The decision was enabled because, technically, Afghanistan picked up the wheat at Kandla, India, so Afghanistan rather than India was using Pakistani territory for transit.The power distribution line faced similar delays because of Pakistan’s refusal of transit rights thus requiring one of India’s largest airlift operations.

Apart from the humanitarian and infrastructure project support that India provides to Afghanistan, what is often missed is the soft power India wields through its NGOs and civil society. India’s projects in Afghanistan are ‘replicas of what India has been able to successfully implement in some part of India or the other’. SEWA trained over 3,000 Afghan ‘sisters’, and continues to operate despite having suffered two fatal terrorist attacks on its team in Kabul. Similarly, Sarhad, a Pune-based NGO funds educational sponsorships for 50 Afghan students to pursue higher education in India.

While India was the largest regional donor and was executing infrastructure projects in each of the thirty four provinces of Afghanistan, the impression was that these activities wouldn’t have been possible if contractors and project implementing authorities didn’t have Afghan National Army (ANA) protection. The question that was often raised, what would be the position in the event of Taliban takeover of Afghanistan?

Protracted Attempts at Pulling out the NATO and US Troops

The US forces first came to Afghanistan in 2001, to flush out Al-Qaeda fighters, in the wake of the 9/11 attack and the UN sanctioned In 2008, the then U.S. president Barack Obama announced plans to send seventeen thousand more troops to the war zone. Obama reaffirmed his campaign statements that Afghanistan is the more important U.S. front against terrorist forces. He said that the United States would stick to a timetable to draw down most combat forces from Iraq by the end of 2011. As of January 2009 the Pentagon had thirty- seven thousand troops in Afghanistan, roughly divided between U.S. and NATO commands. Obama could not redeem his pledge to withdraw the US troops from Afghanistan.

In 2014, at the end of what was the bloodiest year in Afghanistan since 2001, NATO’s international forces – wary of staying in Afghanistan indefinitely – ended their combat mission, leaving it to the Afghan army to fight the Taliban. The US would still have 9,800 troops in Afghanistan. But talk of their imminent pullout gave the Taliban momentum, as they seized territory and detonated bombs against government and civilian targets. In 2018, the BBC found the Taliban was openly active across 70% of Afghanistan.

President Trump outlined his Afghanistan policy in Aug 2017, saying that though his “original instinct was to pull out,” he will instead press ahead with an open-ended military commitment to prevent the emergence of “a vacuum for terrorists.” Differentiating his policy from Obama’s, Trump said decisions about withdrawal will be based on “conditions on the ground,” rather than arbitrary timelines. He invited India to play a greater role in rebuilding Afghanistan while castigating Pakistan for harboring insurgents.2 Later, he opened up negotiations with the Taliban at Doha, Qatar and offered to pull out most US troops if the Taliban agreed to a cease-fire and peaceful negotiations with other Afghan parties.

The process that Trump started has been fast tracked by Biden administration; so fast tracked that most American troops have already left and continue to leave much before his declared deadline of twentieth anniversary of 9/11, even as Taliban’s violence kept increasing, capturing town after town. The United Nations Secretary General’s (UNSG) report noted that the security situation in Afghanistan “continued to deteriorate”. Between February 12 and May 15, the United Nations recorded 6,827 security-related incidents, a 26.3 per cent increase from the 5,407 recorded during the same period in 2020. This probably was waiting to happen: “I worry most when timelines are attached to their pullout, but not conditions,” regrets an Afghan human rights activist.“The Taliban will just wait them out and won’t get into substantive issues.” It’s a view echoed by others.

Orzala Nemat, director of the Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) also lamented, “I wish President Biden had conditioned the troop withdrawal timeline with zero killings on the ground by all parties between May and September”. Of course, the US army had an equally powerful argument: “The US president has judged that a conditions-based approach, which has been the approach of the past two decades, is a recipe for staying in Afghanistan forever.” Such an approach only underscored what Ambassador Sood had earlier said, for the United States, it was a withdrawal agreement, not a peace agreement.

On July 2, the US and its allies exited Bagram airbase, the centrepiece of their presence in Afghanistan and the springboard for their operations there. Self-doubts, disgrace, and regret are coursing by Washington after US troops stealthily bolted from Bagram airbase in Afghanistan in the dead of night on July 2 without even informing local Afghan commanders. Pictures of Afghan troops throughout the nation surrendering to Taliban without a battle amid unfolding chaos at Bagram is triggering questions from US lawmakers and security analysts, with dire forecasts about imminent civil war and the return of terrorism to the area as a result of the Biden administration’s accelerated withdrawal.Three days after on July 5,Taliban forced over one thousand Afghan troops to flee to Tajikistan even as the militant group takes over 6 key districts in northern Afghanistan.The surge of Taliban wins in northern Afghanistan has caused Germany,Turkey and Russia to close consulates in the region.

The Afghans, hardened by decades of fighting, are hardly shocked as they prepare for the return of civil war. Michael McCaul, a Republican lawmaker revealed that Afghan President Ashraf Ghani’s team warned him the departure of US troops would mark “the year of the jihad” and that President Biden will have to own up the “ugly images” of killings, oppression of women, and a humanitarian crisis. Reuters quotes a mechanic in Bagram:“They came with bombing the Taliban and got rid of their regime – but now they have left when the Taliban are so empowered that they will take over any time soon,” he said.“What was the point of all the destruction, killing and misery they brought us? I wish they had never come.”

Amid this expression of sadness, there are reports of fierce resistance from some quarters. Women in Afghanistan’s Ghor province have taken up arms to defend their motherland against the military organisation.Therefore, while some military analysts feel that Kabul could fall just after the last of the US troops leave by August, others feel that Afghanistan is in for a long and bloody civil war.

The Options for India – Dealing with the Taliban

How India fashions its relations with Afghanistan in the emerging scenario where the Taliban is likely to play a dominant if not exclusive role is a critical question. In crafting its relations with a possible Taliban led government, India can ignore the lessons of recent past only at its own peril.

India’s antipathy towards the Taliban have been long and deeply etched. It had made no pretense to go along with US and its ally’s new version of the emergence of a “good” Taliban. When the Taliban was in power during 1996-2001, India maintained no diplomatic presence, let alone a nodding relationship. Since the US and NATO forces were withdrawing from Afghanistan because it was an unwinnable war leaving the Taliban within sniffing distance from power, where exactly did that leave India? Of the four terms of the so called peace agreement of 29 February 2020, one related to intra-Afghan talks. That encouraged India to emphasize the concept of “Afghan-led, Afghan-owned and Afghan-controlled” peace process. It also helped India to bypass the sticky question of accepting or endorsing Taliban’s presence in the peace process consultations.

It is increasingly recognized that India’s Afghan outreach, that of developmental aid, people to people contact and so on relied on the security cover provided by the US and its allies. With that gone, the policies of New Delhi will need a serious re-visit. Still, there were strong voices in India’s military bureaucratic circles that had a hawkish stance towards Taliban and advocated zero engagement. But as Taliban’s ascendancy was transforming into near control, there were voices that favoured interaction.

Speaking at a webinar on Afghan Peace Process organized by India International Centre, Rakesh Sood who was Indian Ambassador to Afghanistan (2005-2008) had made the following observations:

- What we saw on 29 Feb 2020 was not a peace agreement but a withdrawal agreement

- Four issues were critical to this agreement: US withdrawal, cutting off ties with Al Qaeda by the Taliban, ceasefire, and intra-Afghan dialogue

- The second and third conditions were not fulfilled by the The reason for Taliban not cutting off relations with Al Qaeda was easy to see:Taliban had promised to the Al Qaeda that the two groups will remain allies as they have historical ties; and proof of this was the increased level of violence.

- Since nothing is agreed unless everything is agreed, the consequences were there for everyone to see.

Gautam Mukhopadyaya, India’s Ambassador to Afghanistan (2010-13) provided another perspective. Talking to news portal The Print, he said US is once again reverting to its old position where it basically ends up leaving Afghanistan to Pakistan, “They did it in when the Soviets left Afghanistan, and they are doing it now when they want to leave Afghanistan … While on one hand, they fall back on Pakistan when they need them, every US President who has come to power, from President Bush through Obama to Trump also labelled them as the problem. Now again the US seems to be falling back on Pakistan as they get out of Afghanistan”.

Figuring out just who the Taliban are requires a bit of a drill-down. First, the ‘Taliban’ effectively means some 60,000 core fighters, give or take, with several thousand in a situation of flux. Added to that are support groups or facilitators, which some sources number in tens of thousands, as well as local militias who may support them for gain. An increasingly large part of these ‘professional’ fighters have never known any other life. Others are ‘part-time’ fighters, going back to till their fields or ‘regular’ jobs, especially in districts where the Taliban are more or less in control. To both, being a Taliban means more income, and clout in their villages.

Controlling these are district or local commanders, whose job it is to ensure collection of taxes in the name of a ‘shadow government’. Services have to be provided to the local population, which in turn ensures the Taliban a steady supply of recruits, ensuring numbers are sustained in the fighting season. Both these tiers can go on fighting till the end of their lives if necessary. But what they want is a move from shadow to substance; and they’re likely to get just that in large parts of Afghanistan even if negotiations stall.

Second, there are the Taliban field commanders, who have created their own fiefdoms causing considerable unease in the Leadership Council. It is said that Mullah Baradar opted for “reduction in violence” rather than a ceasefire, since he was uncertain whether commanders would actually obey the leadership. Many have acquired their own “business interests”. Field commanders function like corporate honchos, and neither the Taliban leaders nor anyone else can get them to stop fighting unless their interests are assured. The advantage is that their independence gives negotiators a little leeway. The more the divisions, the greater the space for persuasion. But considering the spread in control and interests among different layers of Taliban, it would require different carrots for different levels of commanders.

Apart from anything else, India needs to keep four things in mind. First, violence is not only in the DNA of Taliban but it has used violence in both open warfare as well clandestinely to gain and exercise extraordinary power and influence over friend, foe and the populace.

Second, the umbilical cord relationship of the Taliban with Pakistan. Third, Pakistan uses this relationship to execute its “asymmetric warfare” strategy to respond to the threat that it perceives from India. In fact, one of India’s big ticket projects–the construction of the Afghan Parliament–was delayed by two years because of security fears as no contractors could be finalised. Now the worry was that other projects like the Salma Dam project in the Herat province may also get affected if the security situation worsens.

As far as public knowledge goes, it was in 2019, the then Army Chief and present Chief of Defence Staff (CODS) General Bipin Rawat advocated engagement with Taliban as it cannot miss out “on joining the bandwagon” – different from the official line of “no engagement with the Taliban”. Many people are looking at the opportunity to exploit the vacuum that is being created. Afghanistan is a nation which is rich in resources…there are nations that tend to exploit resources for their own benefit without the benefit going to the community of that nation”, he said adding that the international community must step in to ensure “Afghanistan is for the Afghans.” While he did not name the country, General Rawat was clearly referring to China, which has emerged as the rogue player in global politics.

It was only recently that Qatar’s special envoy for counter-terrorism and conflict resolution, Mutlaq bin Majed al-Qahtani, said that he believed the Indian side was engaging with the Taliban as the group is seen as a “key component” in any future government in Afghanistan. While there has been official denial from India’s side, there is virtual agreement that India has indeed reached out to at least some elements of Taliban leadership. There is high possibility of civil war in absence of political settlement.Therefore, it appears India is moving to protect its interests by opening a dialogue with the Taliban. This is indeed a huge shift. It is believed that India has opened channels with Afghan Taliban factions and leaders.

The Indian outreach is largely led by security officials and limited to Taliban factions and leaders that are perceived as being “nationalist” or outside the sphere of influence of Pakistan and Iran. The outreach includes Mullah Baradar. This is significant as he signed the deal with then US secretary of state Mike Pompeo in February 2020 that paved the way for the current withdrawal of American troops. Baradar held various posts when the Taliban was in power during 1996-2001.

India’s Foreign Secretary Shringla said that “the levels of violence and the fact that despite talks going on in Qatar and other places,Taliban’s relentless pursuit of power through violence has made it an uncertain environment in any sense” and the attempt by the Taliban to steadily expand its influence through “targeted assassinations” and “territorial aggression” as reasons for triggering the uncertainty, it shouldn’t be surprising if it boomerangs.

Suhail Shaheen, member of the Taliban negotiating team and spokesman of the political office of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan (IEA), was quick to say this was a “distortion” of the reality: “That India says Taliban are triggering violence is an effort to distort the ground realities.This undermines their credibility in the Afghan issue,” he said.That the Taliban’s stand has only hardened is evident from an interview he later gave to CNN-News18:

“As far as the ground realities in Afghanistan are concerned, the Indians are living almost in a vacuum. Furthermore, they look at us from their angle of discrimination, bias and hostility.

This is their origin of perception about us but it has not served them in the long run. They are siding with a foreign-installed government in Kabul which is killing its own people to stay in power. India should remain at least impartial in the Afghan issue, rather than supporting an occupation-born government.”

In conclusion, whatever be India’s earlier stance vis-à-vis the Taliban, given the fact that they are likely to effectively take control of Afghanistan in the near future, the government needs to find a way to maintain its presence not only as a humanitarian and development aid provider in that country, but also as a stabilizing influence which can perhaps bring various Afghan elements to a negotiating table and work towards eventual peace and progress foe their people.

Footnotes:

- https://theprint.in/opinion/five-reasons-why-india-should-leave-af-to-pak/376149/

- https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-war-afghanistan