This paper argues that the Sustainable Development Goals not only represent a new strand in thinking about development, they also require a new way of doing which is currently hampered by persistence of old institutional forms and conditioned reflexes that are too bureaucratic, silo-ed and incentivize target-meeting by mere reporting or isomorphic mimicry.

But first let us be intellectually honest and put out the counter view. The idea of sustainable development is not new nor is global goal setting a recent innovation.

At the very latest, the field of forestry and forest science as it emerged during the 19th century used the phrase sustainability and sustainable development to refer to the proper management (and harvesting for timber and hunting permits) of forests. The Elder Toynbee in his Ruskin College lectures on the Industrial Revolution not only coined the phrase but also referred to the ill-effects of deforestation upon urban areas that had no longer green lungs to protect from factory fumes. Fernand Braudel refers to the domestication and decimation of forests in Europe as part of first the agricultural revolution in Europe and subsequent emergence of the industrial economy and society. Gareth Stedman Jones in his work on the deindustrialization of London town describes the encirclement of parks in the city by newly emerging service economy – the warehouses and brokerages with accompanying courts and law firm offices, newspaper and publishing companies and the attendant schools and city universities. So clearly, sustainable development has been a preoccupation for quite some time.

Similarly, development goals and international targets have also been in provenance at least since the post-WWII period of “decolonisation, disarmament and development”.

From the First Development Decade (1950-60) to the International Decade for Women (1975-85), the Alma Ata Declaration on Health for All (1978), the Jomtien Declaration on Education for All (1990), the world community, led especially by donors and multilateral organisations, has regularly set international development targets (IDTs) on a range of issues.

1995 was a particularly fecund year for global target setting. There were a series of summits – International conference on Population & Development at Cairo, the World Summit on Social Development at Copenhagen and the World Conference on Women at Beijing. Each of these important gatherings culminated in a set of goals with regard to population and reproductive health, social development (employment and social inclusion) and gender equality. These goals were quantifiable and time-bound. The Highly Indebted Poor Countries (HIPC) initiative made debt relief conditional upon timebound achievement of targets for growth, employment, poverty reduction and social development.

Subsequently, the Millennium Declaration was endorsed by all member countries of the UN in September 2000 and then the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were set out by the UN agencies based on a collation and rationalization of global goals thus far and the assessment of progress on these targets.

The above potted narrative about global goals has been used by many, in government, NGOs, donor agencies, academia and research community. It would be only natural to presume that the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a warmed-up version of all the global goals and targets that have come earlier and as such a matter of “old wine in new bottles”. This is a view that has been articulated by bureaucrats and NGOs alike and resonated with an equally jaded and cynical audience.

However, a closer examination of the SDGs listed in the UN General Assembly Resolution “Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Social Development” indicates that the above view is both fallacious and inappropriate. If anything, the challenge before the world community is to implement this refreshingly new approach to goal setting with due urgency and innovative partnerships.

Indeed, the first claim to novelty about the SDGs is the inclusion of “strengthening the means of implementation and partnerships” as a distinct goal with specific targets for technological innovation (bringing in AI, Machine Learning, block chain, User Design Experience and a host of disruptive technologies), financial inclusion, capacity development, citizen identity and Big Data. Clearly, the SDGs have much more practical and achievability-orientation in contrast to the ‘global reporting” orientation of the MDGs.

The journey from MDGs to SDGs in India was interesting in that it began with a total hostility on part of the NDA regime. The argument was that not only had India not been consulted let alone involved in the framing of the MDGs and their targets, but in the absence of any donor commitment to provide funds, it was basically a white elephant or an “800-pound gorilla” to use the colourful description by India’s Finance Ministry.

After 2004, when the UPA government came into power, MDGs gradually acquired a veneer of acceptability, given the positive attitude of the then Finance Minister who had written in support of the MDGs when not in power. Still, given the bureaucracy’s preference for inertia and the Finance Ministry’s habitual xenophobic posturing against global agendas, the MDG bandwagon moved rather slowly till the Ministry of Statistics under a dynamic Chief Statistician began the MDG Report process and made it an annual feature since 2008.

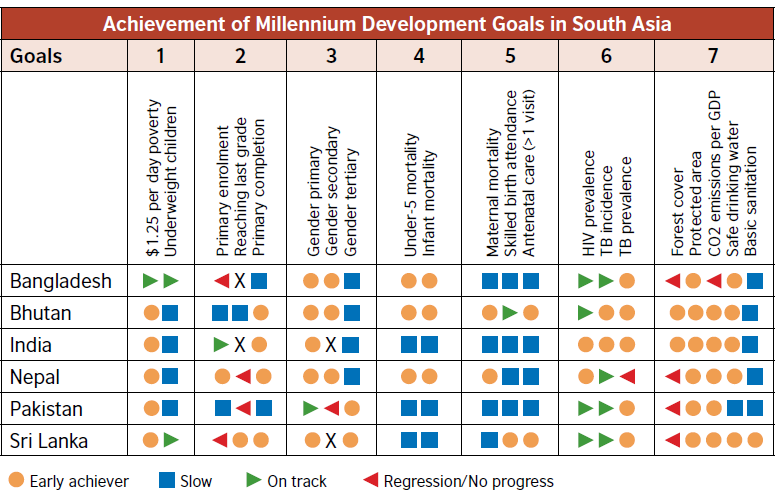

The MDGs triggered new alliances between UN agencies, bilateral donors, advocacy NGOs and campaigns. If we look at South Asia as whole, there was considerable progress. The region saw reduction in extreme poverty by half, near-universal primary education and gender parity in education, halving in the proportion of the population without access to drinking water, made inroads into ending malnutrition, child/maternal mortality and hunger (United Nations 2015).

However, the infographic above (adapted from UN 2015a) shows that the achievement of MDGs has been uneven across goals and targets. There are wide disparities and bottlenecks in the achievement of specific targets. “This is because many countries adopted a fragmented approach to tackling the goals, choosing only to engage with a few goals. Furthermore, the MDGs applied only to the global South, and there was very little ownership of the goals among them, being viewed as ‘externally imposed’ on the developing world.” (Kumar and Khemka, forthcoming).

The SDGs followed a more inclusive and participatory process of framing and templates for reporting, including the latitude allowed explicitly for countries to customise the SDGs according to their specific contexts, constraints and capabilities. Here it is important to clarify that the comparison between MDGs and SDGs is not that of a competition. Nor did the SDGs come out of the MDGs. The two agendas are parallel and interlinked common streams: The concepts of sustainability arise from forest science. Human development arises from Aristotle’s Nicomachean ethics and the debates over basic services and physical quality of life. Together these contributed to identifying development targets – these three streams foreshadowed and contributed to the genesis of both the MDGs and the SDGs.

Sustainable human development is at the core of the 2030 Agenda and the SDGs. The Sustainable Development Agenda is based on the interlinkage of people, planet, prosperity, peace and partnership – closely aligned with the four pillars of human development, viz., equity, efficiency, sustainability and participation,

The SDGs have also received greater traction in South Asia in large measure due to the ground-breaking work done by the Human Development Reports (HDRs) in the region. The HDRs were first launched in 1990 by Mahbub-ul-Haq and Amartya Sen with the goal of placing people at the centre of the development process. Development was characterized by the provision of choices and freedoms resulting in widespread outcomes (UNDP 1990). The HDRs highlight the Human Development Index (HDI) trends in health, education and basic living standards in recent decades. Bangladesh was the first country to prepare the National Human Development Report (NHDR) in Gender in 1993 (HDRO 2004, NHDR Toolkit). Since then all countries in south Asia have prepared their National HDRs, and the concept, methodology and process of human development reporting is part of the regular policy discourse – quite naturally because pro-poor, welfare-ist discourse is a powerful political mobilisation tool. Accordingly, the fundamental principles of human development, viz., sustainability, equity, efficiency and participation are foreground across the SDGs, particularly those pertaining to social development.

The transition from NHDRs to SDG reporting was also greatly facilitated by tool such as DevInfo, VAM, FIVIMS and ChildInfo which drew upon the data from the national and subnational HDRs and also leveraged the credibility arising from the fact that in large federal democracies like India the State HDRs combined often contradictory features of government ownership and editorial independence – underpinned by the participatory process of preparation.

The acceptability of reporting on SDGs in India therefore was facilitated by the prior presence and acceptability of state level human development reports and vision documents. Of course, the policy work entailed in availing World Bank’s DPLs also contributed to an increased receptivity to evidence-based public policy in India (Kumar 2014).

In that sense, the momentum for the SDGs in South Asia is far stronger not because of the MDG reports but because of the HDRs. It is clear that the human development agenda and the human development reports in South Asia contributed to a better grounding, appreciation and ownership of the SDGs.

Sustainability is key to the SDGs and underpins all the goals, demonstrating that the environment is not an ‘add-on’ but is key to the development agenda. While the MDGs maintained a narrow focus on eliminating poverty, the SDGs take the view that social, environmental and economic systems are embedded in each other rather than disparate pillars.

The prioritization of sustainable development and meeting the SDGs is consistent with efforts to adapt to climate change. In fact, the year 2030 is used as a yardstick for the SDGs as all growth trajectories require decarbonisation to occur within the next 15 years, in order to keep global temperature rising beyond 1.5 degrees.

Given that the SDGs are much more consensus-based, country-driven (not donor driven), convergent across social development, economic growth, climate risk resilience and with a strong focus on peace and justice (MDGs could for instance have been achieved by dictatorial methods), the case for treating them as new and innovative is well established.

The institutions of global, national and local governance – the rules of the game and their enforcement characteristics – need to be re-fashioned to meet the challenge of achieving SDGs. Conventionally, goals are met bey setting targets, identifying ministries and departments and implementing agencies to achieve separate targets and the providing funds and people for this purpose. In India, these are done through “flagship programmes” which is a fancy phrase for centrally sponsored government scheme. These are silos within the silos of ministries, each with its different mandates and quirks of ministers and secretaries. Given that India has more than seventy ministries and departments at the central level and on an average a state government has around fifty plus departments, this makes for a mighty machine that is mighty complicated to function with the convergence and clarity of roles and responsibilities that the timely achievement of SDGs requires.

The task of administrative reform is important but perhaps a labour of Sisyphus. It would be more useful given the short time frame for the realisation of SDGs by 2030, to focus on subnational strategies – at the state and local level. Research on policy reform in India has shown that not only have most “best practices” arisen from innovations in specific locations upscaled by responsive state governments, but sustained reform in budgeting, implementation and monitoring has been led by state governments. Since the 1990s, when the imposition of hard budget constraint by Government of India, left the state governments holding the bag for substantial debt and liabilities, several state governments used the crisis of finance as an opportunity to innovate and put in place what were then regarded as novel solutions – mission-mode schemes, user associations, self-help and neighbourhood groups, to expand and improve service delivery. Today these are no longer risky ventures and heterodoxies but part of the routine gamut of public policy. Given the demonstrated viability of new institutional mechanisms at grassroots level, there is a demonstrable willingness to focus on issues like convergence, facilitated by advances both in technology and methodologies of micro-planning, budgeting and M&E. So it is entirely possible to fashion new bottles for the new wine of the SDGs. The challenge therefore is to harness political will and public pressure to ensure that the new wine goes of the SDGs into new bottles of planning, budgeting, implementation, monitoring feeding back into the loop of planning, implementation and monitoring.

References

United Nations 2015, South Asia MDG Report

United Nations 2015a, “Transforming Our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” Suraj Kumar (2014) “Political Will and Subnational Governance Reform in India”, in Jindal Journal of Public Policy, pp.88-108

Suraj Kumar & Nitya Khemka (eds) (forthcoming 2019) Social Development and SDGs in South Asia (Routledge UK.

1 Dr Suraj Kumar is Senior Visiting Fellow at Rajiv Gandhi Institute for Contemporary Studies, New Delhi

2 Dr Nitya Mohan Khemka is Affiliated Lecturer at Centre for Development Studies, Cambridge University, UK.