Introduction to the Sundarbans

Sundarbans is the delta formed by the confluence of the Padma, Brahmaputra and Meghna Rivers in the Bay of Bengal. It is the single largest mangrove forest in the world between India and Bangladesh with India owning 40% of it. The name “Sundarbans” is thought to be derived from Sundari (Heritiera fomes), the name of the large mangrove trees that are plentiful in the area. The forestland transitions into a low-lying mangrove swamp approaching the coast, which itself consists of sand dunes and mud flats and barren land and is intersected by multiple tidal streams and channels. Four protected areas in the Sundarbans are enlisted as UNESCO World Heritage Sites, viz. Sundarbans West (Bangladesh), Sundarbans South (Bangladesh), Sundarbans East (Bangladesh) and Sundarbans National Park (India) – See Fig 1.

Despite several protection acts, the Indian Sundarbans were considered endangered in a 2020 assessment under the IUCN Red List of Ecosystems framework. This makes both the ecosystem as well as the communities extremely vulnerable and susceptible to the calamities of nature. There is serious flooding and water logging in monsoon (which brings the salinity to its lowest) and extreme shortage of water during summers that shoots up the salinity to extreme highs (see vlog). The wide range, therefore, of the salinity, poses a serious threat to both the flora and fauna and makes livelihoods very difficult to manage both at household as well as ecosystem levels.

There have been several studies and documentation on the threats faced by the 102 islands of the Indian Sundarbans, 54 of which are inhabited. For example, Mousuni is one of the 102 islands on the Indian side of Sundarbans facing an existential threat. With homes swept away time and again by raging water and cyclonic effects and agriculture devastated by saline water, several people have been forced to migrate from here and many permanently. As people, mostly youth, migrate seasonally or permanently towards seemingly better opportunities, there are lesser hands left in the household to contribute towards livelihoods.

This, coupled with loss of livestock and land, temporarily or permanently, creates a vicious cycle of poverty that leaves the elder population, women and children vulnerable. For most of these households and communities, fisheries (capture of aquatic organisms including fish) and / or aquaculture is/was the mainstay. With the visible negative impacts of climate change that includes too much (rains, floods) or too little (dry season) water availability at different times of the year, the very high range of salinity fluctuations leaves very little room for both aquaculture as well as agriculture. The livestock do not remain secure as loss of livestock drains out the little resources left with these households.

Figure 1: The Sundarbans between India and Bangladesh

Having talked about the generic scenario above, the paper highlights examples from the Indian Sundarbans by way of observations from several visits and in-depth interactions with Government and Non-government agencies as well as community members in these islands. A lot is being said and only some being done in terms of long-term strategies as opposed to a lot being done on crisis management that turns out to be a band aid approach. What seems to be missing is the proactive approach and strategies. It is evident that while the crisis management strategy is clearly reactive in nature, little is being done as proactive and long-term approach. Even if some is done, organizations, collectives and even individuals tend to act in silos and largely miss out on the benefits of synergies between and amongst them.

There is strong evidence of the seasonal and some permanent migration mostly that of youth, as a result of which, agriculture and other livelihood opportunities is left in a precarious situation. Lack of hands to help out may not be the only reason for failing agriculture that is coupled with declining soil fertility, declining water tables and a very high range of salinity over a period of time. One major and very important observation, both from the visits, discussions and historical perspective is that the flooding in the Sundarbans is becoming more and more unpredictable – too much of water in too little time and sometimes long spells of (usable) water shortage.

One of the approaches that have been tried by the communities is to adapt to changing conditions and rely a bit more on off-water activities such as livestock. However, lack of capital and very little high grounds and unavailability of sufficient land at the household level has discouraged this approach as well.

During a visit immediately after one of the cyclones, it was observed that there were hundreds of families that had to move to higher grounds – the only higher grounds available being the primary and secondary roads. As a result of this, almost for three months, movements were completely stalled and availability of day to day needs including food and medical support was a huge challenge. Some families reported having lived in such conditions for three long months. All agriculture plots were submerged and farmers faced huge losses that included livelihoods, health and well-being in particular.

Seasonal migration from the region is disturbingly high at 74% (Mistri, 2013). We came across stories of both parents migrating to earn a living, sometimes for extended periods of time, leaving behind very young children to the mercy of neighbours. So while the social capital is important and pays back, it certainly can never make up for parents’ absence. That is one of the major reasons many organizations working in the region would want to arrest or minimise seasonal migration by providing sufficiently good livelihood options and opportunities. While some agencies and researchers term it as “environmental migration”, the reasons could be well beyond environment alone though it plays an important part.

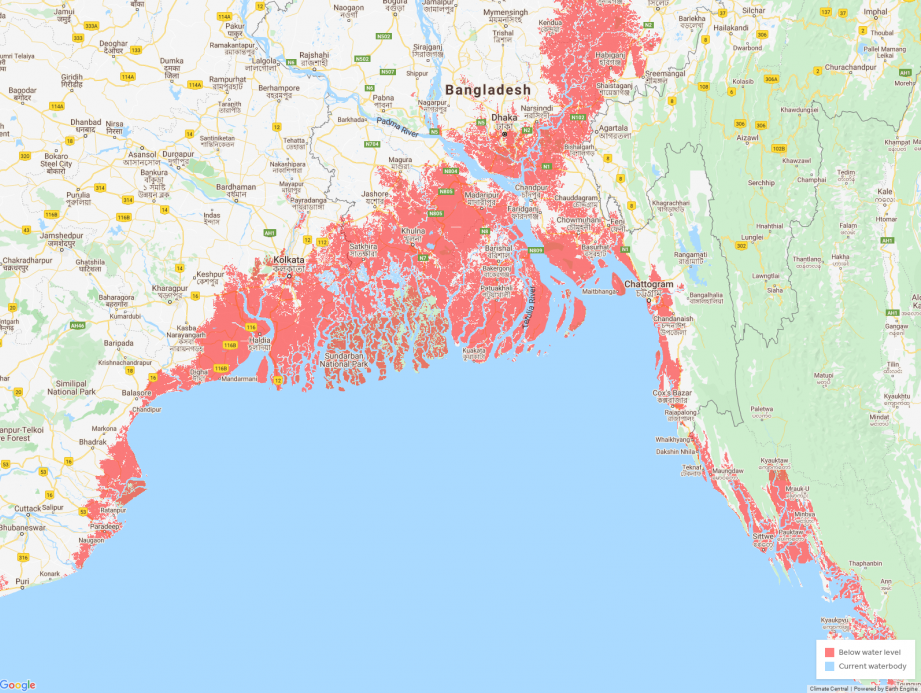

NASA Landsat satellite imagery[1] shows that the sea level has risen in the Sundarbans by an average of 3 centimetres (1.2 inches) a year over the past two decades, and the area has lost almost 12 percent of its shoreline in the last four decades. Along with the Sundarbans, Much of coastal Bangladesh is very close to the sea level. Thus, sea level rise is expected to cause widespread flooding as the climate continues to change. This low-lying area, vulnerable to flooding, is home to 18 million people.[2]

The crisis is coming, and we have to start working on what can be done in terms of mitigation and adaptation. One adaptation strategy could be Amphibious Living – essentially living on water rather than on land. While some work has been done on amphibious housing in Vietnam and Bangladesh (see link below) not much has been done on Amphibious Living as a whole[3].

Amphibious Living Opportunities – The ALO for Sundarbans

What has been stated above is just the tip of the iceberg. After several visits and consultations with local community members, including women and children as well as some NGOs and government agencies, it is evident that these communities will need to quickly adapt to “Amphibious Living”. The title “Amphibious Living Opportunities” abbreviated as ALO (আলো) in the local language, Bengali, means “illumination” or “light” and also signifies “dawn”.

Amphibious living is a means through which communities need to adapt to extreme conditions of climate change. Promoting disaster and climate change resilient livelihoods in alignment with amphibious living will not only help the local communities to shape their livelihoods in accordance with climate change, but also reduce their vulnerability to climate risks and improve their living conditions. Disaster and climate change resilient livelihoods would involve promoting livelihoods in fisheries, agriculture and agri-allied activities.

Strengthening amphibious communities would involve strengthening communities to undertake initiatives for (a) ecological conservation; (b) disaster and climate change preparedness; (c) seeking improvements in infrastructure and services and (d) securing livelihood for all.

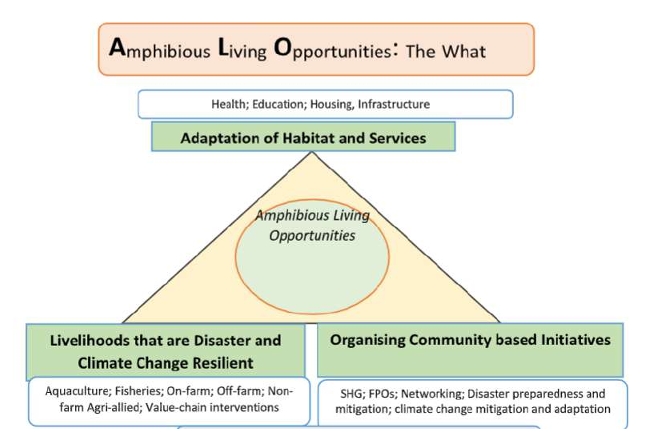

Amphibious living would involve redesigning of the use of physical assets – such as structures to prevent flooding, housing, building and also natural assets such as land and forest etc., which support amphibious living. It is being suggested that the this would involve a three pronged strategy: (A) Focus on basics of living – food, health, education and housing; (B) promoting amphibious livelihoods – through land and water based interventions that would include integrated farming approaches on one hand and involvement of women on the other; and (C) prioritize community based initiatives – building communities to adopt to amphibious living with a focus on SHGs, FPOs, networking, disaster preparedness and mitigation.

Figure 2: The three pillars or “Triad” of ALO

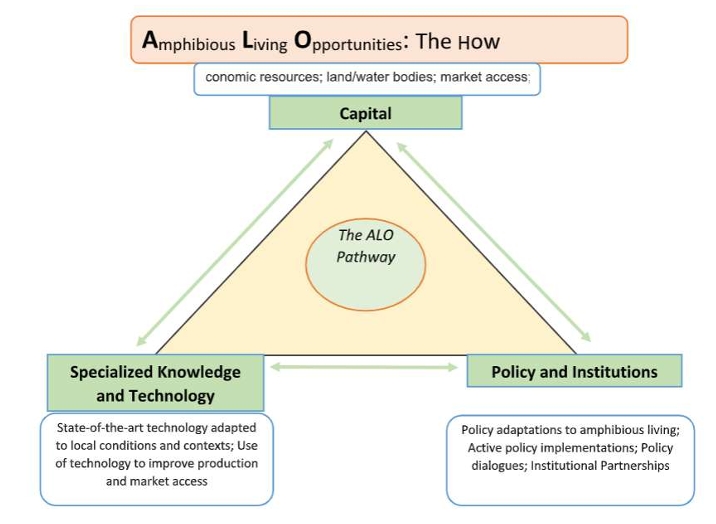

While this is easier said than done, pathways to enable this approach shall have to be put in place (see Figure 3). The three strong pillars of this triad will consist of (A) Capital – economic resources, land/water bodies and access to markets; (B) Specialized knowledge and technology – state-of-the-art technologies adapted to local conditions and contexts, use of technology to improve production and market access; and (C) Policy and institutions – policy adaptations to amphibious living, active policy implementations, policy dialogues among and between stakeholders and institutional partnerships. Based on detailed discussions, some of the most appropriate interventions that can be thought of are being suggested below. The criteria used for suggesting these ideas is based on the following:

- Befitting local context – technically, socially, environmentally;

- Preferably ideas that the relevant organizations and / or the communities are familiar (and comfortable) with or are easy to adapt;

- Preference to high-value low-input crops;

- Appropriate interventions in the value chain;

- Consider natural calamities as limitations (not threats) and meticulously plan ‘around’ it, and

- Encourages partnerships with like-minded agencies;

Over the years, it has been observed that too much of dependence on ponds and farm-lands that are often inundated by floodwaters, takes away the scarce resources that the households have. On the other hand, a large percentage of households are engaged with some or the other off-farm or non-farm activities. By now we have not just a global but also a national and local realization that the climatic adversities are not here just to stay but also become more forceful and unpredictable as we go forward. The planning for the future has to be more efficient, smart and compatible. The idea of amphibious living has become a truth in some parts of the world where coastal lands are being lost to rising sea levels. This idea, however, requires a separate thought process that shall be taken up as appropriate.

Adaptation of Habitat and Services

In light of disaster proneness of the area and the onset of climate change based sea level changes, it is necessary for the habitat – housing, infrastructure – and services – health, education to adapt.

Housing – with cyclone protection

In states like West Bengal which is also low lying, a very common safety measure that has been practiced for hundreds of years is to build their house on elevated land. In most cases, individuals dig out soil from their part of the land to attain this elevation. This serves two purposes – one, the plinth of the house is elevated to a desirable extent and two, a backyard pond is dug out by default. It could be possible that fish became an almost staple food due to these backyard ponds that sprung up by default. However, elevation of the house only caters to normal floods to some degree but the ill-designed houses, mostly huts made of local materials, succumb to cyclones. While most of the efforts to overcome this situation is focused on building stronger (concrete) dikes in the short-run and planting mangroves in the long run, it certainly does not address the need of cyclone proof housing.

West Bengal is among the top four states hit by cyclones frequently. The South 24 Parganas district in West Bengal – home of the Sundarbans, suffered more cyclones than any other district in India. It makes it all the more difficult for people with very little resources to their disposal. While Multi-Purpose Cyclone Shelters (MPCS) along the coastline for tropical cyclone risk mitigation is important and are meant to provide refuge to vulnerable populations at the time of a cyclonic storm and otherwise to be used as a school, community centres etc., it does not cater to improved individual housing.

Sugata Hazra, head of the Department of Oceanography in Kolkata’s Jadavpur University, said: “We need to know why 63 out of around 1,000 villages in the Sundarbans are getting affected repeatedly. We need to find a solution for their safety.” He recommended putting up offshore wind breakers in some parts of western Sundarbans where the impact of cyclones is most pronounced. “Along with strengthening the existing embankment, at least one room in a house needs to be built on a higher plinth to counter flooding and needs to have a concrete roof so that during a disaster the entire family can take shelter there,” suggested Anurag Danda, a Sundarbans expert (Source: www.preventionweb.net).

Mousuni panchayat has listed the damage caused by cyclone Amphan, as it did after cyclone Bulbul. The list shows 93% of the 6,500-odd families in the island and 80% of houses were affected twice. Subhas Acharya, an expert on the Sundarbans, pointed out that the houses built under government-supported schemes were also affected, as the funds were not sufficient to build concrete roofs. After Amphan, residents say there is no point repeating the same housing schemes. They want enough financial support to be able to build concrete roofs that will not blow away in the next cyclone. Only brick houses with concrete roofs survived (Source: www.thethirdpole.net).

Infrastructure – water, power, telecom, roads, jetties

The marked backwardness of the Sundarbans regions and the main hurdle being separate islands could be attributed to the lack of road connectivity and transportation among other infrastructure shortcomings. The prime reasons of creation of Sundarbans Development Board was to increase road and bridge connectivity and other infrastructure of civil nature. Engineering wings were created with the introduction of IFAD Project in 1981-82 and since then civil work programmes have been executed as one of the major programme elements. Department of Sundarbans Affairs has since been implementing its work programme through the Sundarbans Development Board.

It seems ironical that (fresh) water remains a major problem in the Sundarbans, a land that is often inundated by floods. Sundarbans is basically formed out of land surrounded by rivers and creeks. Yet both availability of potable water as well as freshwater for various purposes is seriously short of needs. To add to this, the rivers are saline to extremely saline in nature as is the groundwater in shallow aquifers. Salinity of water limits its use in domestic as well as for agricultural practices including aquaculture.

The deeper aquifers do have safe (fresh) groundwater but are few and far between, sometimes at depths of 300 meters below ground level. While the average rainfall in the region is impressively high at 1600 mm/annum, it lacks proper infrastructure and planning to maximize and hold this water or, for that matter, use it to recharge aquifers. Lack of upland freshwater discharge into these rivers allows the saline sea water to move deep inland. Salinity intrusion in the agricultural field makes agriculture extremely difficult (Source: www.documents.worldbank.org).

Electricity or the lack of it has been a major concern. Less than a decade ago, the solar micro-grid, funded by West Bengal Renewable Energy Development Authority (WBREDA) and implemented by Tata Power was setup. Between 1996 and 2006, the WBREDA had installed 17 such solar power microgrids in the Sundarbans. Initially, the microgrid in Indrapur would supply power for five hours a day, with three to five power outlet points in every household, for a monthly subscription of Rs. 80 and Rs. 120, respectively. However, eventually the power station was defunct. Since 2018, however, several solar grids have come up with a nominal charge per household.

The region is recognized as a backward region in terms of transport and communication with only 42 km of railway, 250 km of metalled road, and about 170 km of unpaved narrow roads much of which has become defunct due to frequent floods. The existing modes of the transport of the region are not able to boost up its development in various sectors. The number of ferry services, number of terminating bus routes and distances of the nearest railway station from the block headquarters are inadequate and quite low barring some exceptions.

As boats are both a means of transport of goods and passengers, as also necessary for fishing, the existence of all-season jetties is very important. The Sundarbans Development Board has a program for construction of RCC Jetties and so 131 such jetties have been built in the area.

Health

Rising salinity and sea level pose multiple health challenges in the region. It becomes worse during floods when movement between islands or even within the island is completely blocked. To add to this, their existing livelihoods makes them spend extended hours in highly saline waters. Shubhankar Banerjee, Founder of NGO Soul which conducts medical camps in the villages on a regular basis, said, “Most of the people in the Sundarbans face stomach ailments majorly related to (in)digestion and acidity because of the saline water. Anaemia and calcium deficiency is another big health issue that they face – both females and males”.

The health care centres too are few and far between. Dr. Sourav Mandal, Medical Officer, Basirhat Health District, said, “We have conducted medical camps and found that people are struggling to make ends meet. One of the reasons behind poor access to health services is transportation. If someone gets a heart attack, they often die by the time they reach the hospital. During labour pain, women have to cross the river and sometimes take a boat ride which could take 4 to 5 hours”.

Education

While several organizations have attempted to bring in quality education in the islands, many schools that they leave behind are severely under-staffed, with broken classrooms – which further fails to draw them back in. “There is a sharp rise in drop-out rates since 2009,” says Asok Bera, a primary school teacher in Sagar block’s Ghoramara island, which is especially vulnerable to floods and submersion. “Here the river snatches our land, houses and homes, and the storms [take] our students,” says Amio Mondal, a teacher at Amrita Nagar High School in Amtali village of Gosaba block, “We [teachers] feel helpless.”

Service Enterprises

While there are some small stores in each of the villages, many of them are just an extension of their huts and caters to essential day-to-day commodities only. Barring exceptions such as fish catching and selling, there are very few established sustainable enterprises in these islands. In islands and villages where community members are linked with enterprises that have a mainland connection (products such as fish, chicken, eggs and to some extent, milk), the prospects look promising. However, these approaches need to be formalized and streamlined in order to create many more avenues and opportunities.

Livelihoods that are Disaster Resilient and Help in Adaptation to Climate Change

There are several livelihoods that exist and more can be taken up by the households. A combination of more than one of the following livelihoods which are disaster-resilient and help in adaptation to climate change, can either be started or scaled up:

Agriculture

- Salinity tolerant rice varieties: There have been reports of use of salt-tolerant rice varieties but it is scanty. Given the local conditions, this can be taken up with certain farms as a pilot. The Knowledge Bank of the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) carries sufficiently good information on this (See link).

- Integrated Agri-aqua systems: This is an appropriate location for vegetable farming as the season can extend a bit longer unless extreme flooding inundates the dikes. If fruit-based multi-tier cropping is practiced on the dikes (Papaya, Guava, Okra, lettuce, pineapple are some examples), the dike of each of the ponds will provide close to 200 sq mtrs of farming land. See example in this video link. This is important as it not only allows to plan and produce in an efficient manner but also that farm diversification is a risk aversion strategy.

Fisheries

- Short cycle fish species and ponds: Given the fact that the havoc of floods followed by its devastation will increase in frequency and intensity over the years, the timing of pond aquaculture is going to be the most important consideration. For example, if June to October is the peak rainy season, it allows for at least six months (December to May) for pond aquaculture even in low lying areas with little or no dike protection. Such ponds should consider two types of crops – one, short cycle species such a Tilapia; and two, the already used Indian Major Carps (IMC) varieties but the size to be introduced to ponds in December to be post-fingerling stage. This will allow the fish to reach marketable size before the rainy season sets in. For ponds that are in higher grounds and are additionally protected by well-established dikes, can have extended periods of fish culture.

- Mud Eel Culture: Monopterus cuchia, also known as Kuche maach in WB, is found abundantly in freshwater marshy lands in several parts of India. While Monopterus eels may not necessarily fetch a high price (IndiaMart sells it for INR 350/Kg), it has a tremendous food value. The breeding season matches with the onset of the rainy season. There are a range of information materials that can be found. These mud-eels can be reared in earthen ponds (see link) to small containers (see link) or in cemented tanks (see link).

- Mud Crab Culture: Mud crab fattening predominates farming practices in Sundarban as opposed to grow-out culture. Locally, mud crab fattening is known as chamber chas and has been practiced since the late 1990s (Nandi et al., 2016) although the contribution of mud crab to fisheries is an age old practice in Sundarbans. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO of the UN) has a very simple and practical Crab Culture manual that can be downloaded from this link.

- Ornamental Fisheries: West Bengal in general and Kolkata is particular is the hub of ornamental fishes. Depending upon the species (both freshwater and brackish-water varieties), it is relatively far less complicated and also not a very expensive activity. Additionally it has a good market demand as well. In the following links, there are some examples from West Bengal. See Ornamental Fisheries of Cichlids; and a more detailed video on Ornamental Fisheries.

- Farmer owned and managed hatcheries: Other than the cost factor, access to good quality seeds and fingerlings is a major hurdle. Pilots of farmer(s) owned and managed hatcheries that will, in addition to providing sustainable source of seeds, fry and fingerlings in the region, also become a primary source of sustainable livelihood. Smallholder fish farmers have to rely heavily on outsourced seed supply and therefore having one in the community goes a long way. Given the adversities of the environment, it also makes sense to do so as it can be done at the household/backyard and elevated lands.

Bee Keeping and Livestock Rearing

- Bee keeping: The name Sundarbans comes from the famous Sundari tree and the scope of producing organic honey coming straight from the Sundarbans could be well placed. This can be done both by individual households as well as informal and formal collectives. This is also important from a futuristic point of view. This is already being done in the Sundarbans (see link).

- Backyard poultry farming: Several of the households, though, have backyard poultry, there numbers are meagre (sometimes as little as 5 to 10 birds per household). If this can be scaled up between 30 to 50 birds per HH, it can become an important livelihood activity catering to both food security as well as income generation. There are several examples of this being practiced in the Sundarbans (see link).

- Black Bengal goat: This variety, though mostly black, is also grey and white, is a prolific breeder and though may have very little milk value, is known for its meat and skin. It is highly resistant to common diseases and survives without formulated feed if grazing grounds are available. An adult male goat can gain weights up to 25 Kgs. In many parts of West Bengal and Bangladesh, this variety of goat means a lot to landless and poor households and communities. (See link).

Non-farm livelihoods

- Tourism as a composite livelihood sector

The Sundarbans Tiger Reserve is a major tourism destination and a small number of local people participate in the tourism sector as vendors, boatmen and guides. However, rarely any household subsists entirely on tourism-based income since such jobs are seasonal (Does Tourism Contribute to Local Livelihoods? A Case Study of Tourism, Poverty and Conservation in the Indian Sundarbans: Guha & Ghosh, 2007). A majority of the local service providers operate with very little or no capital investment. Yet households participating in tourism-related activity are better off than those who do not. Some of the advantages of tourism coupled with other livelihood options are:

- Additional incomes though seasonal, offers an opportunity and scope for taking it up as an enterprise;

- The sector requires diverse skills but also provides an opportunity for those unskilled;

- Carries a potential for linkage with local enterprises based on the varied needs of tourists; this also provides an opportunity for local artisans and crafts;

- Given the importance of wildlife conservation, this sector can not only cater to the need but also amplify the cause;

As of now tourism is restricted to winter months that are pleasant and also have easier access to the islands given there are less chances of rain and floods.

How to make these livelihoods sustainable?

In addition to making them disaster and climate change resilient, there are at least three requirements for making these livelihoods sustainable:

Taking an Enterprise Approach: People have to move from subsistence to surplus production for the local and distant markets. This means they have to begin with the demand side first – produce what can be sold in addition to what they have to consume for themselves. This requires access to new opportunities of the kind listed above, and mastering their underlying technology and skills.

Starting with Own Capital: The second aspect is to mobilise capital for these new livelihood enterprises. Institutional credit is a predominant source of finance and plays a pivotal role in the development of an economy. Given the limited presence of banks, own funding is the way to go at the beginning, till say INR 10,000 and later may be from SHGs and microfinance institutions, till the amount of investment is below INR 100,000. But as the enterprises grow and some at the higher scale have to be set up, the investment per enterprise may be up to INR 1,000,000 per household and this will require bank financing.

Partnerships with Market Actors: Given the limitations of financial resources and / or lack of access for both individuals as well as communities, getting into sustainable partnerships create avenues. An example from the Sundarbans is that of “Kejriwal Honey”, one of the largest exporters of honey from India, that have partnered with local communities and have provided opportunities to households by providing training, infrastructure (bee boxes, etc.) and facilitation. The other kinds of partnership that is emerging is with established collectives such as FPOs etc.

Organising Community-based Initiatives for Adaptation

The Sundarbans region is characterized by lack of electricity, safe drinking water, health services, educational facilities, and has poor communication network. Additionally a large percentage of people belong to socio-economically backward category. As if this was not enough, the seasonal and / or permanent migration particularly that of the younger generation, adds to the hardship. The vicious cycle consists of many more negatives, most of which has been discussed in details in the earlier sections. All of this leads to limited livelihood opportunities, constraints of health, low and uncertain agriculture productivity and extremely high unemployment rates. Under such circumstances, actions by individuals or a few households is not adequate to move the needle. What is needed are organised community based initiatives. We give below a few examples:

Women’s Self-Help Groups and SHG Federations

The concept of Self-Help Groups was primarily brought in as a tool to empower women, especially in communities where the role of women was no more than running household chores. From a study conducted for a representative sample of the women-run SHGs under the aegis of Sandeshkhali LAMPS, it has been noted that since joining the SHG movement, the economic condition, decision-making power relating to expenditure, status within the family and the society has increased favourably for the women members.[4]

Fish Farmers’ Producer Organization

FPOs are becoming very popular and successful in several parts of the country with huge plans of thousands of more FPOs in the country. However, there are very few examples of FPOs in Fisheries. Recognizing the importance and potential of the fisheries sector, the Government of India launched a flagship scheme, Pradhan Mantri Matsya Sampada Yojana (PMMSY) (visit www.ncdc.in). PMMSY will be implemented over a period of five years from FY 2020-21 to FY 2024-25. As announced in the Union Budget 2020, 500 Fish Farmers Producer Organizations/Companies (FFPOs/Cs) would be set up to economically empower the fishers and fish farmers and enhance their bargaining power.

Panchayats – Gram Panchayat and Panchayat Samitis

The primary unit of local self-government under the 73rd Amendment of the Indian Constitution is the Gram Panchayat, which is quite empowered in West Bengal. It has devolution of powers, funds and functionaries. There are three sources of funds – local body grants, as recommended by the Central (14th and 15th) Finance Commissions, funds from centrally sponsored schemes such as MGNREGA and funds released by the state governments on the recommendations of the State Finance Commissions. Each Gram Panchayat has an appointed Secretary and at the Panchayat Samiti (Block) level there are a number of officials for different functions. Thus it is very important that Panchayats in the area buy into the idea of working towards amphibious living opportunities.

Cooperatives

There is a long history of cooperatives in the Sundarbans. Sir Daniel Hamilton had started the cooperative movement in the Sundarbans in 1902 and since then, various cooperative societies have come up with the support of NGOs such as the Tagore Society for Rural Development of Rangabelia in Gosaba. The government has established several Large-Sized Multipurpose Co-Operative Societies (LAMPS) in the area and these need to be oriented towards amphibious living opportunities.

Amphibious Living Opportunities: How to Actualize These?

Figure 3: The three pillars of the ALO pathway

Capital

Given the critical situation that has been described in the earlier sections, it is evident that none of this will be possible without adequate support of capital – economic resources, land/water bodies and eventually access to appropriate markets. Capital is required at three levels:

- Restoration of common property resources and creation of resilient public infrastructure. This will largely have to come from international and national sources such as the Green Climate Fund[5], and the Government of India coastal area schemes, NREGS, etc.

- For collective value addition, enterprises and common facilities which serve a large number of primary, household level micro-enterprises. For example, a fish processing factory, which buys fish from individual fishers, adds value and markets, much like the AMUL model in dairy. This type of capital will have to come from private sector entrepreneurs and bank loans.

- For primary, household level micro-enterprises. As already suggested, this will have to come from household savings, borrowings from family and friends, loans from SHGs and MFIs.

Specialised Knowledge

Each Amphibious Livelihood needs expert knowledge, its extension, and skills to implement the knowledge. To enhance productivity and market access, even the resource poor communities now have some degree of access to smart phones, for example. Being isolated from the mainstream market and technical support has taken its toll. There are various avenues by which these communities can benefit by way of use to technologies that can be adapted to local conditions and contexts.

Inter-Institutional Collaboration – The Panchmukhi Samvaay

No single actor is capable of addressing the development problem alone. The Panchmukhi Samvaay or Collaborative Pentagon provides a practical structure for the implementation of inclusive and sustainable development. Its five sides are (1) Civil Society Institutions; (2) Government including elected Panchayats and Municipalities (3) Private Enterprise Sector – from micro to corporate (4) Financial Institutions and (5) Knowledge Institutions including Universities and the Media. The community is at the centre of all this. This is depicted below:

A Call to Action

As the dark prospects of cyclone-disasters and climate change induced rise of sea level loom over the Sundarbans, the communities need to be helped to usher in the new dawn of ALO – Amphibious Living Opportunities, comprising (i) adaptation of habitat and services (ii) livelihoods that are disaster and climate change resilient and (ii) organising community based initiatives.

This is a call to action at various levels – individual households, small collectives, larger collectives and community in general; to adapt the habitat as well the livelihoods to the upcoming change. They will have to get together and prioritise activities in terms of urgency, ease, returns and importance – things that can and should be done immediately, those that are mid-term and eventually the long-term ecosystem improvement approach.

They will have to work towards achieving institutional synergy – along the lines of the Panchmukhi Samvaay or Collaborative Pentagon suggested above. And all this will have to done urgently, they have only a few years to respond.

References:

[1] https://thediplomat.com/2020/05/in-the-indian-sundarbans-the-sea-is-coming/

[2] https://scied.ucar.edu/image/sea-level-change-bangladesh

[3] https://floodresilience.net/resources/item/beat-the-flood-flood-resilient-homes-in-bangladesh/

[4] (Source: www.igi-global.com – Handbook of Research on Microfinancial Impacts on Women Empowerment, Poverty, and Inequality; 2019).

[5] https://www.greenclimate.fund/sites/default/files/document/funding-proposal-fp084-undp-india.pdf