Today when the entire world is struggling to get rid of COVID-19, we as a global community must also acknowledge its root causes and act to not invite future zoonotic pathogens. The solution lies in respecting nature, respecting wildlife, respecting bio-diversity and limiting encroachment by humans. This solution can help to address two big problems the world is facing today- climate change and transmission of zoonotic pathogens such as COVID-19. Yet, various international ongoing negotiations related to climate change have not yielded any tangible result to reduce destruction of the environment by humans. Similarly we have not learned anything from previous examples of interspecies transmission of pathogens resulting from destruction of biodiversity.

Various scientific studies have found that spread of zoonotic pathogens such as Ebola, SARS, Bird flu and now Corona is due to over exploitation of biodiversity. Like other previous zoonotic pathogens, Novel Corona (COVID-19) is also transmitted to humans through wet markets in China. A study conducted on transmission of various zoonotic pathogens in 2017 found that interspecies pandemic such as spread of HIV, H1N1 influenza, Nipah, Hendra, SARS and Ebola are strongly related to global land use changes. It further revealed that “the invasion of natural ecosystems and the growth of dense human settlements—as well as the growth of global trade and mobility—are driving increased rates of interspecies contacts and the interchange of parasites and pathogens that can develop into global pandemics[1].”

In India, the COVID-19 has affected millions of people. Migrant labourers are worst affected due to nationwide lockdown. They have lost their livelihood and most of them are starving in different parts of the country. A large number of them have managed to travel back to their villages. But even in villages, they don’t have enough to earn livelihood. The ongoing slow-down of Indian economy and now lockdown has badly affected the economy. The revival of the economy will take some time, so finding jobs even after withdrawal of lockdown especially in urban areas is not that easy. Now in this difficult situation, the already underemployed rural economy will get additional labourers, who have migrated back to villages.

To address this challenge, the government needs to invest more in the rural economy through various schemes. It is also a good opportunity for the government to invest in programs related to its international commitments related to climate change. With this India can achieve three major goals.

- One, it will provide employment and income to millions of migrated labourers who have come back to their native villages,

- Two, it will help in achieving climate change goals and meet international commitments

- Three, it reduces the risk of local spread of zoonotic pathogens, by rejuvenating specie habitats

This article attempts to highlight the problem (jobless population), solution (employ them in regeneration of natural resources – land water, forests, leading to higher growth and sustainability) and the means to achieve it (financial resources and programs). This strategy was first advocated in 2018 in the context of overall jobless growth and rural distress. The weblink reference to that paper Jobful Growth is given below. [2]

Jobs Post COVID-19

Exodus of migrant labourers from various cities in India after the announcement of nation-wide lockdown on 25th March 2020 was reported by various media houses. Various experts believe that this exodus will continue even after withdrawal of the lockdown. By then many people would have lost their job as the economy is badly affected, the high cost of living in cities makes it difficult for many to continue to be in cities and wait for a new job and finally in the time of chaos and uncertainty people would like to be in their native places with their family and relatives.

According to a rapid survey conducted by a NGO ‘Jan Sahas’ published by the ‘Quartz India’ reveal that over 80% of daily wage migrant workers fear it will run out of food before the end of lockdown announced on 25th March 2020[3]. While the lockdown has been extended by the government of India for another 19 days, it is going to be a very difficult time for the majority of migrant daily wage people stranded all across the country.

According to the Economic Survey Report of 2017, the magnitude of inter-state migrant labourers in India was nearly 9 million. Moreover, as per the census-2011 the total number of internal migrants in India (both inter-state and intra-state) was 139 million[4]. Major sources of migrant labourers are states like Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Uttarakhand, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Punjab. Major destination states include Delhi, Maharashtra, Telangana, Andhra Pradesh and Kerala. Various reports suggest that labourers in large numbers from all across the country are willing to go back to their village.

Workers gathering in large numbers during lockdown in cities like Delhi, Lucknow, and Mumbai indicate that a large population of labourers will anyway go back to their home even after the withdrawal of lockdown. A daily wage carpenter Mr. Jai Prakash from a remote village in Allahabad district of Uttar Pradesh has lost all hopes from Mumbai city. He told me over phone that, he is desperately waiting for the withdrawal of the lockdown so that he can go back to his village.

| “For quite some time, finding wages in Mumbai was difficult. But, now with this lockdown and Corona crisis, it will be even more difficult to find wages. It is going to be very difficult to survive hear. Chances of finding jobs in my own village are also bleak, but I will go back to there any way. I am waiting for the withdrawal of the lockdown.”

Jai Prakash Vishwakarma |

The Reserve Bank of India recently in its biannual monetary policy report said that the Indian economy has been drastically altered by the Corona virus outbreak. The lockdown due to COVID-19 has badly affected the Indian economy which was struggling with the prolonged slow-down for many months. The report reads, “COVID-19 now hands over the future, like a spectre[5]”. With all these signals it is clear that the rural economy will have to accommodate another huge influx of workers for next few months (or probably a year) after withdrawal of the nationwide lockdown.

Millions of Jobs in Regeneration of Natural Resources – Jal, Jangal, Jameen

India has been concerned about its rapidly degrading natural resources especially land, soil, water and forest. According to an estimate by TERI in 2018 land degradation through various processes in India cost around 2.5 per cent of the country’s GDP in 2014-15[6]. The study of TERI in 2018 estimated total investment required for reclamation of land degraded by five major processes namely water erosion, wind erosion, forest degradation, water logging and salinity. The study found that India requires Rs. 2948 billion (2014-15 prices) to reclaim 94.53 million hectare degraded land as per latest survey by SAC, Ahmadabad.Assuming an increasing in costs since then, we can round this off to Rs 4000 billion in 2020-21. Thus the nation needs to spend Rs 4 lakh crore, or about 2 percent of the 2019-20 GDP to address Regeneration of Natural Resources – Jal, Jangal, Jameen.

India assured the world about its commitment in the latest conference of parties (COP-14) of United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) held in New Delhi in 2019. The Prime MinisterMr.NarendraModi announced its Land Degradation Neutrality (LDN) target at COP14 of restoring 26 mha of degraded land by 2030. India is also an important player in world climate policies in UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). Along with many other commitments, India as part of its INDCs committed to create an additional carbon sink of 2.5 to 3 billion tons of CO2 equivalent through additional forest and tree cover by 2030.

India has also emerged as a responsible country to protect its biodiversity. India is part of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UN-CBD). The convention covers protection of biodiversity at all levels – ecosystem, species and genetic resources. In accordance with the commitment of UN-CBD, India has prepared its National Biodiversity Targets (NBT) and is committed to achieve them. The 20 listed NBTs of India includes reducing rate of degradation, fragmentation and loss of natural habitat, appropriately addressing issues of invasive alien species, sustainable management of agriculture, forestry and fisheries and ensuring genetic diversity of cultivated plants. India is committed to achieve all above mentioned targets to contribute in global strategies to combat, adapt and mitigate adverse impact of climate change. However, not much has been invested in these sectors. Various schemes for regeneration of natural capital including the Green India Mission are under-funded. An enhanced investment to achieve all above targets and commitments will not only expedite our effort but also generate a huge opportunity of work especially in the rural area.

Using MGNREGA as the Flagship for Natural Resource Regeneration

Currently the MGNREGA is one of the biggest programs which provide opportunities to earn wages up to 100 days to labourers registered under this program. Official data shows that more than 266 million workers are registered under this program; however, only 116 million workers were active in the last financial year[7]. Data for previous few years suggests that the average days of employment is less than 50 days per family. As noted by Arnab Bose in a recent RGICS Paper on Status of MNREGA[8]:

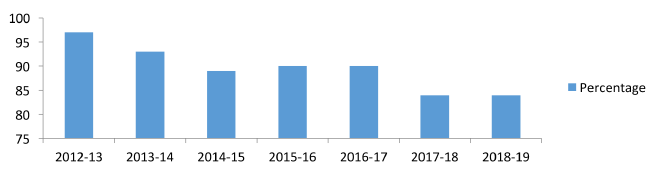

“MGNREGS is a demand driven scheme where any worker that demands work needs to be provided with work within 15 days of the demand. However, the households provided employment as a percentage of households demanding employment has seen a steady decline from 2012-13 to 2018-19. As shown in figure 1, in 2012-13, 97% of households that demanded work received employment but this has declined to 84% over the last two years. “

Figure 1: Number of Households Provided Employment as a Percentage of Households that Demanded Employment

Source: MGNREGA MIS Reports from 2012-13 to 2018-19 PRS

It should be noted that while above chart talks of “households” the reality is that in a household, many times, more than one person needs and seeks work. The MGREGA website[9] lists the number of job cards issues as 13.66 crore job cards were issued (which is issued one per household for every household where at least one adult member is seeking work).

The website says there were 26.61 crore workers, thus averaging 1.95 or almost two active workers per household or per job card. However, of all these, 11.69 crore active workers and 7.6 crore active job cards In FY2018-19 and a total of 267.96 crore person-days, the highest ever, were generated in that year, making an average of 50.9 days of employment per household.

In FY2019-20 a total of 264.46 crore person-days were generated under MGNREGA. The number of persons who worked was 7.87 crore. This actually implies an average MGNREGA worker got only 33 person days of work, though thefigure more commonly used is for number of days per household, which was 48.3 days on an averageduring the year.

The number of active workers seeking MGNREGA work this year may rise to as high as over 12.5 crore due to the fact that by the time the COVID lockdown is lifted on 3rd May, 2 to 3 crore migrant workers would return to their villages and almost all will be without work. If we want to revert to the logic of number of households (job cards) then we can safely assume at least 10 crore job card holders out of the 13.66 crore job cards issued will seek work for at least one member form the household. That means 10 crore persons, and if we want to meet at least half the promise of NREGA, that means 50 person-days or 500 crore person days in this distress year.

The government has allocated Rs. 61,500 crore for MGNREGA for the financial year 2020-21. This allocation is marginally less than the amount allocated for it in FY2019-20. The MGNREGA portal computes the average cost of generating wage employment per person-day at Rs 264.77 in 2019-20, which included the material costthe material cost (24.71%), the wages of semi-skilled and skilled workers and the administrative cost of 4.72%. As the Finance Minister has already announced on 27th Mar 2020, an increase in wage rate to Rs 200 per day. With a raise in wages by Rs 25 per day, this has number is already likely to be about Rs 300 per day per person-day of work generated.

Thus an allocation of Rs 61,500 crorewill not be able to generate even the budgeted 280.76 crore person days of employment, evenif we assume that State Governments are able to put up their matching 25% contributionof material and overhead costs. If we aim at least 50 days of work in this distress year during the year for 10 crore households with one person per household,that is 500 crore person days or an all in cost of Rs 150,000 crore at Rs 300 per day,Therefore, a substantial increase, by nearly 2.5 times the existing allocation for MGNREGA is required.

Where this will come from is a separate question and many fiscal experts are grappling with it. But it will have the double benefit of curbing rural poverty, hunger and unemployment, while regenerating the productive base – jal, jangal, jameen, (land, forest, water), of rural India which will yield a fillip to growth to the agricultural, allied and forestry sectors, and have a very positive effect on the environment. In addition, since a number of studies[10] indicate a benefit-cost ratio of water conservation projects to be in the range of 2.0 at a discount rate of 7% pa, the investment is very beneficial for economic growth of rural areas.

Some other points to be noted are:

- The work related to Natural Resources Management requires very less material assistance.The main need is of water conservation for which we need to dig millions of farm ponds, small community ponds and percolation tanks, none of which require significant material component. Therefore, the material-labour cost ratio can be revised from 40% to 30% this year by mandatorily increasing the share of labour cost. This will discourage unnecessary construction of masonry and concrete small structures even when those are not needed. It will benefit more labourers.

- The share of NRM regeneration related work under MGNREGA should be increased substantially. In the guidelines issued by GoI on 15th April while announcing COVID lockdown relaxation for MGNREGA works, it has been specified that priority should be given in MGNREGA to irrigation and water conservation works. This should be interpreted in a hydrologically sensible way, thereby permitting treatment of land (both public and private) as also of degraded forest land in the catchment watersheds

- Only registered workers are entitled to apply for jobs under this program, many migrant workers do not have job cards to apply under this scheme. So, on the spot registration of such workers is required to accommodate them within the scheme.

- The ceiling of 100 days of work per family needs to be extended to ensure a long term guarantee of a job for this section of the distressed labour force.

- Few months ago the Union government released Rs. 47,436 crore rupees of CAMPA fund to 27 different states. This amount can also be used through the MGNREGA system to ensure equitable distribution of resources.

- Funds under other related schemes such as Green India Mission, Water Mission and the Building and Construction Workers’ Welfare fund can also be utilized through the MGNREGA system to enhance its efficiency and impact.

Footnotes:

[1]https://academic.oup.com/ilarjournal/article/58/3/343/4107390

[2]http://www.rgics.org/wp-content/uploads/Jobful-Growth%E2%80%93How-to-Achieve-It-in-2019-2024.pdf

[3]https://qz.com/india/1833814/coronavirus-lockdown-hits-india-migrant-workers-pay-food-supply/

[4]https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2017/10/india-has-139-million-internal-migrants-we-must-not-forget-them/

[5]https://www.livemint.com/news/india/covid-19-hangs-over-the-future-like-a-spectre-rbi-report-11586443195104.html

[6]https://www.teriin.org/sites/default/files/2018-04/Vol per cent20I per cent20- per cent20Macroeconomic per cent20assessment per cent20of per cent20the per cent20costs per cent20of per cent20land per cent20degradation per cent20in per cent20India_0.pdf

[7]http://mnregaweb4.nic.in/netnrega/all_lvl_details_dashboard_new.aspx

[8]https://www.rgics.org/wp-content/uploads/Rights-Based-Legislations.pdf

[9]https://mnregaweb4.nic.in/netnrega/all_lvl_details_dashboard_new.aspx accessed on 23rd Apr 2020 at 5 pm

[10]See for example: Sahoo, SK (2006) Cost Benefit Analysis of Watershed Development Programme: