Tax system in India and Trends: In the budget presented on the 5th July 2019, the maximum marginal income tax rate has been raised to 42.7%. This has led to questions about whether this tax rate is too high, and whether it will decrease incentives to work and increase tax evasion. In India, many public services such as law and order, public health, social security, water and sanitation, public education, environmental protection, and public transportation, are poorly funded and delivered. We also see high and increasing inequality, driven primarily by the lottery of birth. These two problems feed on each other. One way to both improve the delivery of public services, and secure more equitable growth, is a progressive taxation policy that raises more taxes from those who are very well off.

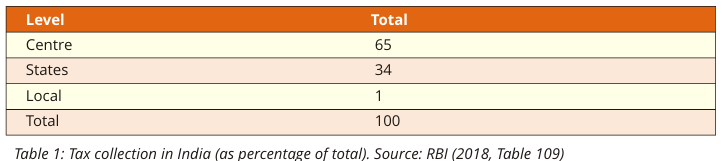

Trends in tax revenue: The tax-GDP ratio in India has been increasing gradually over the past 5 two decades. In the year 2017, the taxes were 17.8% of the GDP. Table 1 indicates the percentage breakup of the tax collections.

It is evident from Table 1 that the centre collects 65% of the total tax. However, most of the expenditure obligations (58% of the total government expenditure) are in the domain of the 6 states. This highlights the importance of the Finance Commissions in ensuring a fair distribution of resources. This also indicates how necessary it is for State Finance Commissions (SFCs) to allocate revenue to local governments more effectively.

Principles of taxation: There is broad acceptance that tax policy and administration should confirm to a few basic principles:

- Efficiency

- Equity

- Effectiveness

It should be noted that these three are inter-related. For instance, a lump-sum tax might be the most efficient from the point of view of minimising distortions. It might also be the most easily enforceable. However, it would fail the test of equity, since a poor person would owe exactly the same tax as a rich man.

Efficiency: Taxes can change decisions about what, and how much, to produce and consume. This substitution away from activities that are taxed is referred to as tax distortion. Distortions lead to a dead-weight loss, reducing the social surplus, even if the taxes improve the overall social welfare.

This analysis helps us identify two ways to reduce tax distortions. Firstly, the lower the tax rate, the lower the distortion. Governments can achieve a low tax rate by taxing a broad base of taxpayers. This is called the Broad Based Low Rate (BBLR) approach.

Secondly, the greater the drop in the demand caused by the tax, the greater the distortion. Thus, if high taxes need to be imposed, they should target inelastic tax bases.

Equity: While taxes are primarily aimed at financing public expenditures, they are also used to promote equity. There are two primary types of equity to consider: horizontal and vertical.

Horizontal equity is the idea that similar people should receive similar tax treatment. For instance, if two people earn similar amounts of income, their income tax outgoes ought to be similar. Vertical equity refers to the idea that those who earn more ought to pay more, through proportional (flat-rate) or progressive tax rates. Vertical equity can help redistribute income within society and reduce inequality.

Effectiveness: The effectiveness of tax administration determines how well the objectives of tax policies are met. But this effectiveness can itself be a function of tax policy. Complex tax laws are difficult to understand and enforce. In terms of administration, complexity of tax laws can lead to tax evasion and to rent-seeking by tax administrators.

Policy questions: In the light of the discussion above, we can now consider some key issues of tax policy in India.

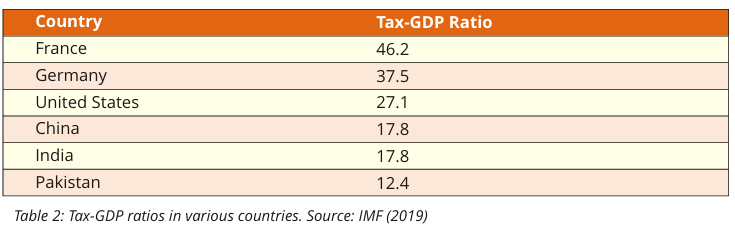

Under-collection of Tax: Many countries collect much higher tax than India. Table 2 presents a comparison of India against some countries at different stages of development. It can be seen that countries such as Germany and France have very high tax rates. Even the United States, which has a powerful tradition of “small government”, has a tax rate much higher than that of India.

The author estimates that accounting for the per-capita GDP and the share of revenue from natural resource rents, the average tax-GDP ratio of a country with India’s characteristics is 20.0%. This is about 13% higher than what India collects today.

Inequality and Taxation

There is an ongoing debate about the effectiveness of tax policy in actually reducing inequality. High taxes on corporates may drive out businesses, impacting their employees negatively. Implementing a progressive tax system comes with increased costs of administration and compliance, and higher economic distortions.

However, there are also voices that strongly call for higher taxes as a path towards less inequality. In Piketty and Qian (2009), the authors claim that “Progressive taxation is one of the least distortionary policy tools available that controls the rise in inequality by redistributing the gains from growth.”

Taxation of corporates and capital gains: In India, income from Long-Term Capital Gains (LTCG) is generally taxed at a rate of 20%, after adjusting for inflation through indexation. LTCG on equity investments is taxed at just 10% (without indexation). Thus, the effective rate of tax on capital gains income is quite low. In contrast, the return to labour (wages or salaries) is taxed at a rate that can be as high as 42.7%.

This discrimination is sought to be justified by positing that tax policy should encourage capital accumulation, since accumulation of capital leads to high incomes for labour. Since Corporation tax is already levied, it would amount to double taxation of dividends, or capital gains on equity, were taxed. Also, imposing tax on capital gains from equity, or on dividends, raises the cost of capital, which can lead to reduced entrepreneurship and fewer jobs. While capital accumulation certainly should be encouraged, extreme tax bias towards capital and against labour can lead to a rentier society.

Municipal finances: Generally, finances should follow functions. In the context of municipalities, this would mean that they should have the ability to raise resources that are necessary to perform the necessary expenditures. However, historically, municipalities have suffered from low fiscal capacity. They rely heavily on transfers from the States and the Centre to finance their budgets.

The Constitution does not assign any power of taxation to municipalities directly. Instead, the state governments assign certain tax powers to the municipalities. They include taxes on property, advertisements, non-motorized vehicles, octroi, professions, trade and callings, and entertainment taxes. With the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST), this authority has been restricted, since several of these taxes have been subsumed under the GST.

The 73rd Amendment mandated the constitution of SFCs. These were to recommend how the state’s revenues were to be distributed to the urban and rural local governments. However, in many states, this has not happened effectively. In some states, SFCs have not been constituted in time. Sometimes their recommendations are rejected without reasons. Often their recommendations regarding financial issues are acted upon, but their recommendations dealing with systemic issues are ignored.

Agricultural Income: In the constitution, agricultural income is not taxable by the centre, though it can be taxed by states. In practice, there is no tax on agricultural incomes in the states either. This violates both horizontal and vertical equity. Another major issue with the lack of taxation of agricultural income is that it enables evasion of tax.

Taxation in the 2019-20 budget: The latest budget presented in July 2019 is a mixed bag as far as taxation policy is concerned. Given that the government has appointed a committee to review direct taxes, it was hoped that a beginning would be made towards simplifying the income tax law. This hope was belied. Instead, multiple new exemptions and incentives have been added to the tax laws, making it even more complex. This includes changes in the provisions regarding interest deductions on housing loans, and deductions to industries in the areas of electric vehicles, Lithium-ion batteries, semiconductors, photovoltaic cells, and laptops.

The maximum marginal rate on personal income tax has now been raised to 42.7%. This can lead to people choosing not to work, and/or attempting to evade taxes. While there was some anticipation of a reintroduction of estate tax, it did not materialise. Further, there has been no attempt to increase the base of the tax. This budget is moving further away from the ideal of a low tax on a broad base.

On the Corporation tax side, this budget has reduced the tax rate on most companies. However, the dividend distribution tax, and the un-indexed equity capital gains tax remains on the books, which means that the same income is taxed multiple times.

Lastly, a ‘faceless’ assessment system for income tax is to be rolled out. While this can help reduce rent-seeking and harassment, the effects might well be counteracted by the increased complexity and higher tax rates.

References

International Monetary Fund. 2019. “World Revenue Longitudinal Data.” http://data.imf.org/?sk=77413F1D-1525-450A-A23A-47AEED40FE78. Isaac, T M Thomas, R Mohan, nd Lekha Chakraborty. 2019. “Challenges to Indian Fiscal Federalism.” Economic and Political Weekly 54 (9). Economic; Political Weekly. https://www.epw.in/system/files/pdf/2019_54/9/SA_LIV_9_020319_TM_Thomas_Isaac.pdf. Piketty, Thomas, and Nancy Qian. 2009. “Income Inequality and Progressive Income Taxation in China and India, 1986-2015.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1 (2): 53–63. http://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/app.1.2.53.

Footnotes:

5 International Monetary Fund 2019

6 Isaac, Mohan, and Chakraborty 2019