Introduction

The Natural/Organic farming movement in India has had several stalwarts impacting thousands if not lakhs of farmers. From Shripad Dabholkar to Bhaskar Save to Deepak Suchde to Subhash Palekar, many have spent time on the ground trying to educate farmers on the dangers of chemical laden farming, monocropping, etc.

They have promoted organic/natural farming with a multifaceted approach of traditional seeds, multicropping and livestock integration. The basic methodology is to adopt techniques from traditional practices which will reduce the need for purchased inputs and improve soil health.

We also have had people like Bernard of Auroville, Kapil Shah of Jatan Trust, Gujarat, Pamayan Balasubramanian of ADISIL, Tamil Nadu, Dr.G.V.Ramanjaneyulu of CSA (Center for Sustainable Agriculture), Hyderabad, Claude Alvares of OFAI (Organic Farming Association of India), Goa, Usha Soolapani & Sridhar Radhakrishnan of Thanal, Kerala, Nel Jayaraman of CREATE, Tamil Nadu, Ananthoo & Ramasamy Selvam of Safe Food Alliance, Tamil Nadu, Kavitha Kuruganti of Alliance for Sustainable & Holistic Agriculture (ASHA), Kiran Vissa of Rythu Swarajya Vedika, Sahaja Samruddha of Karnataka amongst others who have spent time with farmers, training people, working on policy interventions, setting up the alternative ecosystem of sustainable farming and safe food.

Together, all of them have kept the fight against industrial agriculture going, despite the pressures of dealing with lobbies of the World Trade Organization (WTO), Big Agro-MNCs pushing GMO in seeds, heavy use of pesticides and fertilisers.

If there is one amongst this fraternity, that rose to insurmountable heights inspiring lakhs of farmers, urban and rural youth, women and making even policy makers and politicians take note, it was Dr G Nammalvar, a former agricultural department officer who could not stand his job of promoting what was bad for the soil; so, quit his job and became an important cog in the wheel of the natural farming movement of Tamil Nadu. This report aims to contextualize the growth of natural farming movement in Tamil Nadu, reasons for its flourishing, and the most pivotal role played by Dr Nammalvar in its growth and sustenance for years to come.

Tamil Nadu and the impact of the Green revolution

Tamil Nadu is one of the success stories of the Green Revolution with large scale adoption of hybrid seeds, borewells, mechanisation and much more. We also embraced the White revolution despite having no milch breeds and currently stand close to the top in milk production in India. However, all these successes came at a price. Between 1960-61 and 2009-10 the total cultivated area in Tamil Nadu decreased from 7.2 million ha to 5.83 million ha and the net sown area has decreased from about 6 million ha to 5.03 million ha during the same period (Table 1) [1]. However, this reduction in cropped area has been compensated by the increase in productivity of crops so that higher production has been possible.

Table 1: Rainfall, net sown, cropped, and irrigated area by various sources

Area in lakh hectares. [1][2] [3]

| Variable | 1960s | 1970s | 1980s | 1990s | 2000s | 2010s |

| Rainfall (mm) | 928 | 918 | 842 | 959 | 1009 | 823 |

| Net sown area | 60.26 | 61.33 | 56.22 | 56.32 | 50.35 | 47.41 |

| Gross cropped area | 72.00 | 74.23 | 66.77 | 67.29 | 58.31 | NA |

| Area irrigated by | ||||||

| Canals | 8.82 | 8.18 | 5.75 | 6.27 | 4.94 | 4.26 |

| Tanks | 9.12 | 8.94 | 8.18 | 8.35 | 7.48 | 6.66 |

| Wells | 6.44 | 10.83 | 11.05 | 14.67 | 16.10 | 17.79 |

| Other sources | 0.41 | 0.34 | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.05 |

| Net irrigated area by all sources | 24.79 | 26.36 | 24.96 | 27.75 | 27.36 | NA |

| Gross irrigated area by all sources | 32.69 | 35.23 | 31.09 | 33.94 | 31.02 | NA |

It is quite clear that the acreage has reduced as the push for irrigated cultivation, as seen in the increase in well irrigation (including both bore wells and open wells), has led to farmers preferring well irrigated cultivation over rainfed or surface irrigated.

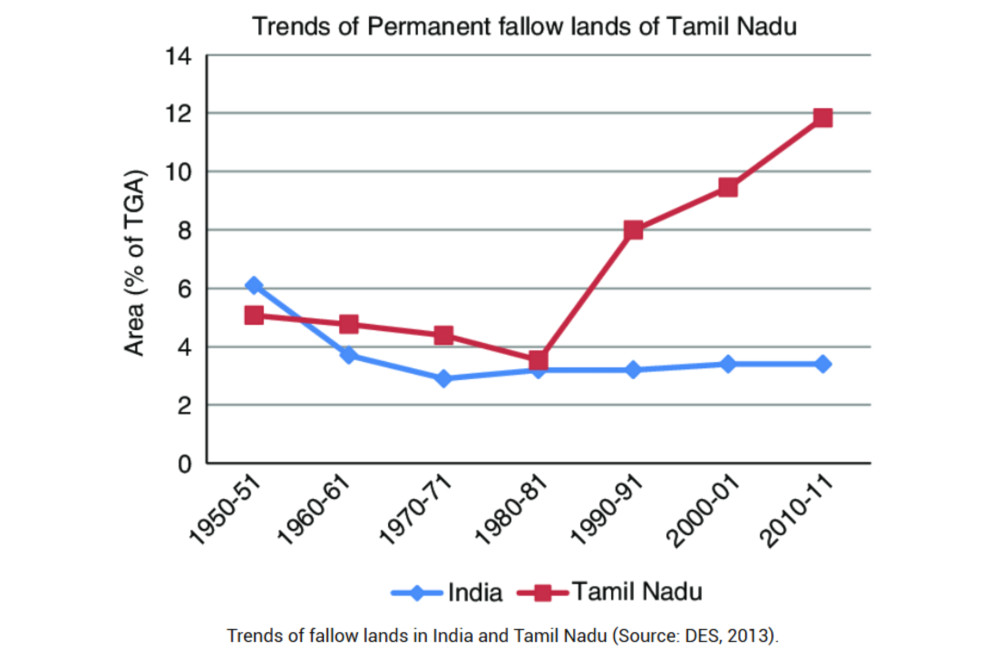

Tamil Nadu has seen a rapid decline in rainfed cropping and a corresponding rapid increase in permanent fallow lands (figure 1) [4]. Although we cannot attribute this only to the preference for irrigated cultivation, as other factors such as industrialisation, urbanisation have changed land use patterns significantly.

However, there has been a marked shift toward high-cost irrigated cultivation of paddy, sugarcane, and turmeric in Tamil Nadu since the 1960s. There are two-fold reasons for this industrialization and urbanization, and the resulting deagrarianization.

- Next generation farmers from privileged backgrounds quitting agriculture as better economic and social prospects became available (before 90s), and

- Next generation farmers from both privileged and non-privileged backgrounds quitting agriculture (after 90s) – not because better economic and social prospects are available; but due to a variety of distress reasons pushing them out of agriculture.

In other words, the agency of the farmers to choose their way of livelihoods has gradually eroded. The story is not hugely different from other parts in India where modernisation took its toll on rural incomes and livelihoods and damaged the ecological security of the people. It is 2020 now and we are faced with a serious need for introspection on what was lost and the answers we find from that introspection will mark the direction in which we need to proceed further.

From the 1970s there has been a pushback all over the country, in terms of people bringing awareness on the ill effects of modernisation and its associated narratives in the name of food security.

Agro-ecological movements led by individuals have helped create a parallel ecosystem of production, processing, marketing, and this gives hope in the times of a massive push towards modernisation by a globalised policy making model. In Tamil Nadu, Dr Nammalvar played a pivotal role in one such movement.

The uniqueness of the natural farming movement in Tamil Nadu – late 60s to late 80s

Tamil Nadu stands apart here. Alternate thinkers are not relegated to the fringe here and are celebrated by the mainstream. It was never only about natural farming but creating a mindset change and taking that message to the people. The natural farming lobby, yes, it is a lobby, and a powerful one at that; has been instrumental in stopping Genetically Modified (GM) seeds, making the government pull back a Livestock Trading act and many such policy changes.

Mobilisation for such initiatives happens in the posh areas of Chennai at the same time as the hinterlands of Cauvery Delta or Kongu region (Western Tamil Nadu) or any such place here. Farmer leaders are hosted by people from a liberal, modern mind space in Chennai when they visit to address issues or lobby with the government. Any national level meet or protest, the contingent from Tamil Nadu will always have traditional farmers alongside new age farmers who bring alternative perspectives on ecology and economics.

Tamil Nadu has the highest number of organic stores, eco-friendly businesses and even a private equity led venture fund to incubate the same. This development is not restricted to urban pockets but prevalent across the state.

To understand the current resistance to conventional farming and the growth of organic and eco-friendly businesses, one must go back to the 1980s and understand the dynamics of farming and rural transition in Tamil Nadu. Beginning from 1980s, large farmers and their next generation – sons and daughters started to exit agriculture as a business.

In pre-liberalized India, for large farmers, incentives from farming were reducing, whereas the other prospects increased. Parallelly, narratives around food and food consumption started undergoing many changes in Tamil Nadu including rapid industrialization and commercialization of livestock.

Broiler chickens were introduced in 1975. The breed reaches critical mass for commercial production in only 6-8 weeks, whereas native country chickens require about 6 months. The myth of red meat – beef and mutton being unhealthy, compared to chicken, also began to spread widely during this time.

The seeds of the green revolution paved way for further commercialization and industrialization of farming in India and Tamil Nadu. One of the major changes happening during this time, not only in farming, but throughout the trading economy was that – it was changing from a producer-centric narrative to a consumer-centric narrative. Even during the colonial times, when trading posts were set up throughout the coast of India, whatever was grown and manufactured in the immediate vicinity was traded. The producer remained the primary point of locus in manufacturing – either in farming or other industries, and had a much-heightened sense of agency, which waned away in the 1980s.

Dr Nammalvar’s journey – from late 1960s

As Tamil Nadu’s rural regions were undergoing deagrarianization in the 80s, Dr Nammalvar was working parallelly on social forestry and natural farming.

Disillusioned by the policy and ground level results of the green revolution, where the Union Government took most of the decisions in Delhi on what to be grown in Pudukkottai down south, he left his job in Kovilpatti Agricultural Regional Research Station in 1969.

He joined the Island of Peace with the Nobel Peace Prize awardee Dominique Pire and worked in Vadakarai village in the Kalakad block of Tirunelveli district.

Working at Vadakarai, Nammalvar delved further into the green revolution narrative that changed farming. He began an informal way of training, and understanding of existing practices and structures, rather than imposing top-down pre-packaged solutions.

In a video interview in 2001, he states that “In India, farming used to be a lifestyle. In these 40 years, we have made it into a business.” [5]

While large scale narrative transitions were happening throughout the country and in the developing world on the nature of farming itself – from a lifestyle that was farmer-centric and producer-centric to a consumer-centric narrative, Nammalvar was working at the grassroots level in Vadakarai focusing on rural development through local agricultural practices.

He was trying to make agriculture a sustainable lifestyle, combined with overall rural development. At this time, his popularity was limited to his immediate circles and the budding natural farming movement in Tamil Nadu. At a time when Government jobs were most sought after, Nammalvar was able to not only quit his job, but also find like-minded individuals in Tamil Nadu to pursue his venture.

Though grassroots level movements, such as the natural farming movement flourished in Tamil Nadu – it was largely due to the culture, open-mindedness and respect generated for powerful grounded narratives that made Tamil Nadu unique. Unlike other states such as Sikkim or Andhra Pradesh, where natural farming movement has picked up pace, the movement in Tamil Nadu was built bottom up, without much or any state support.

Kavita Kuruganti of the Alliance for Sustainable and Holistic Agriculture (ASHA) states that “So what we see is – in Tamil Nadu as a movement is essentially a civil society movement – led by Nammalvar almost singularly. I mean, there has been a number of other farmers – having smaller areas of influence, and that is something very different about Tamil Nadu. And the fact that it has been solely civil society and led by someone with a high degree of integrity – also means when someone adopts this path – they are not likely to leave it at the first hardship.

So, it is a more sustainable organic farming movement – compared to other states. I can say that about Kerala also. Not because of figures like Nammalvar, but because of the Endosulfan tragedy (Kasaragod district) and so on. So, there it is a societal like – movement. Obviously, it will be more lasting in – you know, how deep it runs and how long will it run, and people helping out each other, influencing each other. I think that is something very positive about Tamil Nadu” (personal interview, 2020).

Speaking about the lack of state sponsored growth of natural farming movement, Ananthoo of Safe Food Alliance notes that “(In) Tamil Nadu – there is no institutional growth. Tamil Nadu has seen – exemplary farmers – here and there. That is also the way (it) always (has) been – very few people. Except Erode, there has not been a contiguous group of farmers. Everywhere you go and see. If you are talking about 10-12 years back, every town would have some people like this (advocates for natural farming). For sugarcane, you can tell some five people across Tamil Nadu. For onion, someone. Vegetables, someone. They were always separate and disjointed. Also, because there was no programmatic or government approach.

There were some people around him (Dr Nammalvar). If he goes to Puliyampatti, he will go to Gomathi Nayagam. He will talk to people around him. I think it is also a very slow – it is also organic in growth – his own methodology too. He has spoken to many people around Tamil Nadu. So, some people will recognize – ‘yeah, this is right, and that’s how it has slowly changed’. There was no programmatic approach at all. We have never done that except for few NGOs here and there. And Government also does not really come in. They (Government) will do (something) for 3 years, and then disappear. Here it is deep rooted, because everyone who changed, they changed with a conviction – for a reason. They found something that is more interesting and more assuring.” (personal interview, 2020).

Dr Nammalvar played an instrumental role in this bottom-up development of the natural farming movement in Tamil Nadu. In 1973, joined by fellow agriculturists who were embedded in the counterculture to green revolution and focused on natural farming – such as Vaanamaamalai and Nallakannu, Dr Nammalvar moved to Anjetty in Krishnagiri District, and continued his informal way of education. He learned from the local agricultural practices, while engaging the farmers with his knowledge of farming as well. One important aspect to notice here is that – both Anjetty and Vadakarai, as well as other places where Nammalvar had worked are considered dry and not very conducive to farming. The fact that he could work a sustainable model at such places further shows his credibility, and the drive to show that ‘if natural farming can be done in this dry and not considerably suitable place, it can be done anywhere’.

Uniqueness of Dr Nammalvar in the Natural Farming Movement

Among his peers in the natural farming movement in Tamil Nadu, Dr Nammalvar was unique in many ways. For example, while Government agricultural offices were mired in bureaucracy, not enabling a common farmer’s approach easy; Dr Nammalvar was quite easy to approach in both spirit and word. He made his narratives simple and easy to understand.

One organic farmer, Ram says “Among farmers, what he (Nammalvar) could do was – practical solutions he could provide on their field, and simplistic ways in which he could explain it to people, which people can relate to.

Very few people have the capacity to bring that aspect of technical competence as well as capacity to reach out and communicate to a wide section of people. (His) Capacity (to do that) is – rather unique” He continues “Second(ly) – he could translate across boundaries – he could equally talk well to scientists, academics, politicians, and – that ability to reach out to people and I mean, he had his challenges- but I don’t think he gave up on anybody. He just kept going. And third(ly) – (it) is personality – definitely he is a very charismatic person.”

He recalls an event in Chennai against the mechanization of slaughterhouses. “So, he turned up. He kind of came a little bit late. There were people – academics, people, it was a public meeting – but also there was press there. At the end of the meeting, the entire crowd was like, walking behind him, (even though) we had several other people who are considered eminent in the stage.

He spoke about the economic aspects of why cattle have to be protected, and after that – towards the end, he also gave practical solutions – because there were several housewives and common people sitting in the audience. After he finished talking and came down – one lady (who was in the audience) kind of bowed to him, and to her he said – ‘naan kadaisila sonnathu ketteengla. Ungalukku kaaga than sonnen’ (Did you hear the last thing I said? I said that for you.)

He was a real charmer. He also takes in mind the audience, and he could talk to all of them at the same time. He could be forceful, and most importantly, somebody who could maintain himself – easily approachable and reachable for everybody. He was very easy to reach. Most people created several gates. He didn’t.” (personal interview, 2020). In a bottom-up, grassroots level movement like the natural farming movement, such absence of gatekeeping, keeping the cause above the person, as well as delivery of complex, nuanced knowledge in a simpler, relatable way made the ideas deep rooted wherever Nammalvar traveled and spoke to the common man.

Besides extensive traveling, Nammalvar also wrote and spoke to everyone in the hinterlands of Tamil Nadu about natural farming. He wrote a total of eleven books, wrote articles in Pasumai Vikatan – still one of the current major publications in Tamil about agriculture, and appeared in primetime TV shows to talk about natural farming. Through his extensive traveling, writing, and talking – he created an ecosystem for natural farming to thrive in Tamil Nadu.

Nammalvar, Green Revolution and input-centric farming – late 70s & 80s

Dr Nammalvar preached that the green revolution favoured mostly the fertilizer, pesticide, and insecticide international companies, rather than the Indian farmer. In the process, the eco-chain of natural farming – that combined livestock management, water management, social forestry, management of commons was broken, and every single aspect of it was commodified. Seeds imported and spread by the Government as high yielding varieties from the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) in Philippines replaced the traditional rice varieties of India. Thousands of paddy varieties that existed in pre-independent India disappeared.

Input costs of a farmer increased rapidly, and his returns and profits reduced marginally. As a result, the net income significantly reduced or went in the negative, leading to poverty traps and farmers’ distress and suicides. In such a context, Dr. Nammalvar’s narrative not only about natural farming, but also about a different way of lifestyle that was more grounded, and in-sync with nature and the ecosystem was readily taken up. He not only articulated the problems of conventional farming, but also provided a solution. For example, Dr Nammalvar often quotes a Tamil agricultural proverb which says.

“Adi mannukku, nadu maatukku, nuni veetukku”

Meaning that the roots (adi) after harvest are left for the soil, the stalk (nadu-middle) were fed to the livestock, which gave milk and manure to the farmer, and the grains (nuni-top end) went to the house. From the livestock, milk went to the house, and the manure went back to the soil for the next cycle – creating a self-sustaining loop. The livestock gave us what we wanted – milk and manure, while we gave the livestock what we do not want and need – the stalk. Under green-revolution, mineral fertilizers which were produced from petroleum were subscribed by Governmental agencies to increase the fertility of the soil.

Pesticides and insecticides, when added to the plants, increased the toxicity of the soil. They also entered the food chain, including mother’s milk. Seeds, which were taken from the previous crop or sourced locally, then had to be bought from the Government and other companies every season. As a result, farmers became debt ridden, and over the course of time, despite the introduction of technology such as borewells, free electricity schemes in Tamil Nadu, farming became a less prestigious job, eventually resulting in deagrarianisation.

Parallelly, as a wave of deagrarianization, farmer distress and input-centric conventional farming was developing, Dr Nammalvar led and contributed to the resurgence in natural farming methods. To show that natural farming methods and social forestry, without any chemical inputs, can be a viable option, in 1982, he started developing around 20 plus acres of social forest at Ammangkorai, Pudukottai district. In 1979, he started a society called Kudumbam (family) for farmers to be self-sufficient and do ‘poison-free’ (free of mineral fertilizers, insecticides and pesticides and other inputs) farming. As of 2001, he had worked with over 6000 farmers converting more than 20,000 acres into natural farming [6].

After attending a 4-week training course by the ETC Foundation in Netherlands on ecological agriculture in 1987, Dr Nammalvar founded a network called LEISA India (Low External Input and Sustainable Agriculture) as part of the AME Foundation in 1990. In the same year, he started the Ecological Research Centre for rain-fed cultivation in Pudukkottai district. Though, in the larger picture, aided by the state, conventional agriculture was taking firm roots in Tamil Nadu, a resilient, bottom-up, grassroots level movement of natural farming led by Dr Nammalvar was slowly gaining mass-movement parallelly.

Globalization and agriculture in Tamil Nadu – the 1990s and early 2000s

Counter-narratives to green revolution and input centric farming in terms of natural and ‘poison-free’ farming had spread throughout Tamil Nadu leading to the 90’s, by word of mouth, writings, formation of farmer organizations, and mostly through informal networks. Even if people did not perform natural farming, the narrative that natural and organic farming as a much more holistic way of farming, and a better lifestyle spread in Tamil Nadu. As these parallel changes were taking place, India’s economy got liberalized in 1991 and opened for foreign investments, and structural changes that prioritized the market economy.

Tamil Nadu is one of the foremost states to reap the benefits of liberalization of the economy started in 1991. Tamil Nadu went through a slew of urban centric development and a steady increase in GDP. Manufacturing units were attracted from abroad to be set up. Industrial corridors and Special Economic Zones came up in Tamil Nadu. If we look at the urbanization data from 1981, 1991, 2001 and 2011 of Tamil Nadu, we can see a clear-cut pattern towards urban-centric development and migration.

According to 2011 census, Tamil Nadu is the most urbanized state with about 42.47% of the population living in urban areas with small and medium towns spread across the state [7]. It is estimated that by 2030, 67% of Tamil Nadu’s population will live in urban areas and only 33% in rural areas [8]. Urban population grew at 27% in 2001-2011, whereas rural population grew at 6% during the same time [9]. As a result of urbanization, agricultural land loss is happening throughout India. In 2001-2010 time period, Tamil Nadu had lost about 45,312 hectares of agricultural land to urbanization and industrialization, mostly in the peripheries of existing cities and towns [10].

To improve the yield of crops – especially paddy to meet the demands of the population, various schemes are brought forward by the Government such as the system of rice intensification (SRI). Though the yield per hectare has increased in the recent past, it is still yet to be seen if it has reached a threshold in terms of increasing the yield. The other issue with respect to urbanization’s effect on farming has been the competition for water between urban and agricultural needs.

For example, in Thiruvallur district, adjoining Chennai, private borewells set up in villages have been pumping water from Thiruvallur to meet the growing water needs of Chennai [11]. As a result, agricultural activities are severely affected in pockets surrounding the bore wells, leading to exit from agriculture, distress, as well as changes in cropping patterns. Tamil Nadu, which especially has many smaller cities and towns – and continuing to rapidly urbanize, need to come up with a sustainable urban development program that needs to consider the surrounding rural areas. If not, further industrialization and urbanization would lead to further farm distress and reduction in overall crop growth.

Though the population of Tamil Nadu is not rapidly increasing (fertility rate of TN is 1.6), increase in urbanization would also lead to more pressure on existing farmlands to improve their yield, potentially giving rise to increased chemical inputs. This could potentially also lead to decreased food security of Tamil Nadu, as high pressure on yields concentrated in lower acreage would mean increased risk of crop loss due to pest, disease attack as well as extreme climate events – for which Tamil Nadu is highly susceptible.

It could also mean increased loss during transportation and storage of horticultural produce, as smaller pockets of land would be producing for urban regions far away. The solution lies in identifying and incentivizing decentralized meeting of demand and supply – in that locally produced foods are consumed locally – even within Tamil Nadu. This will reduce transport and storage loss, sustain the diversity of farmlands and the crops, and prevent against extreme climate events, pest, and disease attacks.

Globalization narrative is also one of the major drivers of urbanization throughout the world. After the fall of the Soviet Union, international politics and globalization intensified and began to expand its influence in many major fields. The World Trade Organization – which replaced the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), was formed in 1995. Genetically Modified (GM) crops, which were being developed and introduced in the US in the 1980s was introduced commercially in India in 1996 [12] with Bt Cotton eventually occupying a large market share.

Because of the neoliberal policies starting from 1998 onwards, and further expanded since 2005, agricultural management and perception further shifted. Earlier, big farmers and their next generation were exiting agriculture and found good success in other areas. Even smaller farmers and their next generation, who quit agriculture found success, thanks to the IT, medical and other higher educational revolution that happened in Tamil Nadu [13].

However, much more recently, the movement away from farming – especially the next generation of farmers has been due to macro level changes in urbanization and industrialization leading to distress in farming – rather than a voluntary moving away towards prosperity. In that sense, not only the real income levels, the collective and individual agency of farmers has also been decreasing over time.

Starting in 1980s, Tamil Nadu allowed for private engineering and medical colleges leading to much better enrolment and increase in human capital in the industrialized and ‘skilled’ sectors. The number of engineering colleges doubled in late 2000s, with 251 engineering colleges in 2007, as compared to 553 colleges in 2013 – with an overall annual admission increasing from 73,953 to 1,82,491 students per year [14].

Correspondingly, unemployment rates and underemployment rates have also increased with graduated engineers predominantly not employed in the engineering sector. As of 2018, nearly 1.6 lakh engineering graduates are unemployed [15]. According to an aspiring minds report, nearly 80% of India’s engineering graduates are not employable in engineering related sectors, and in that Tamil Nadu was one of the worst performing states occupying the bottom of the table [16].

Though the deagrarianization had seen a corresponding increase in ‘skilled’ human capital, most of the newer graduates continue to be unemployed or underemployed, working outside their area of training. This shows that there is an inflated supply of engineers, but relatively low demand in the Tamil Nadu economy.

The globalization economy had two contrasting results moving towards the extremes in agriculture in Tamil Nadu. Many big and small farmers were exiting farming for other industries. On the other end, another group of people such as Dr Nammalvar, Venkatachalam, Pamayan, Anthonysamy, Satyamangalam Sundararaman, Arachalur Selvam moved towards taking the organic farming movement to the lay person and resisting the changes.

Lots of structural and institutional arrangements were changing in India. As a result of such changes, not just in agriculture, for economic success and upliftment, the role of working capital became paramount.

Not just economic capital, the importance of social capital also went up – as traders and manufacturers who are well networked became more prosperous, whereas new entrants who had to learn the rules of the game were at a distinct disadvantage, which had worsened since 1980s.

In the last two decades, if you look at data, you will find that there are less OBCs in top level management positions and even lesser SCs and STs. At best, for most people reaching the mid-level ranks in the private corporate sector was itself a dream and most languished in the bottom rungs. The cost of acquiring and education to reach there had a heavy toll on the agricultural economy. The risk associated with accessing capital also increased tremendously.

The microfinance model for lower income households to access risky capital became widespread in the early 21st century throughout developing countries. India and Tamil Nadu were no exceptions. The United Nations named 2005 as the “International Year of Microcredit” [17].

This suggests two things that – access to capital has become more and more important for economic success, and the lower income households were finding a hard time to access capital. Microfinance systems worked towards this problem and became successful.

However, most of the microfinancing focused on self-help groups and other small loans, and not towards agriculture. Institutional priority sector lending is available, but there is a heavy bias towards cultivation of paddy or sugarcane, which is mostly irrigated, and not for any rainfed crops or even processing, storage.

The inability of rural farmers to mortgage their rural lands, and for younger farmers who do not have assets to their names to declare as collateral to access institutional credit has further worsened the problem – leading to farmers not able to access credit at all or turning to loan sharks with extremely high interest rates.

Gradually, over time because of lack of access to financial credit and financial cushion in a world rapidly giving increased importance to capital, the role of farmers as primary producers and most important part of the society was gradually relegated. Farmers’ net income reduced, and the overall crisis intensified. The % share of GDP from Agriculture and allied sectors has been steadily declining in Tamil Nadu. It was about 24.57% in the 1980s to 21.85% in 1990s to about 16.88% in the 2004-2005 financial year [18].

Legacy of Nammalvar and the Natural Farming Movement in Tamil Nadu 1990s, 2000s and 2010s

With respect to deagrarianization and development, more and more people in Tamil Nadu began to question the globally existing paradigm, which was becoming increasingly exploitative, and at the same time resisting social growth of the underprivileged. Mid and late 2000s, and the first half of 2010s further entrenched this narrative and increased an already existing global unrest.

Stream of underlying unrest, especially with respect to environmental issues became mainstream in Tamil Nadu. Protests against Koodankulam Nuclear Power Plant (protests from 1990), the pollution of Sterlite Copper in Thoothukudi (protests since 1993), Hydrocarbon extraction project in Cauvery Delta (since 2009) and the Neutrino project in Theni (since 2005) became peoples’ movements.

During this time, Dr Nammalvar actively involved in such environmental issues, and widely travelled and became much more popular throughout Tamil Nadu. Nammalvar inspired the next generation of youngsters, farmers, and activists by being a man of action, and not simply rhetoric. For example, the revoking of the Neem patent by the European Patent Office (EPO) in 2000 to US Department of Agriculture and the multinational WR Grace to produce a fungicide – was considered a landmark victory for peoples’ movements against big corporations.

The case filed by many organizations including Dr Vandana Shiva of Research Foundation for Science, Technology and Ecology (RFSTE) in 1995, eventually became fruitful in 2000, when the EPO squashed the patent citing the existing knowledge of the usage of neem in India. It set a precedent for future patent rights issues. Dr Nammalvar, along with Dr Vandana Shiva was present at the EPO office in Munich in 2000 to protest the patent.

His involvement in the neem patent issue was two-fold – in that directly he provided support for the case, and indirectly, he spoke about the injustice of the patent in India and spread the knowledge to the common man about the importance of neem, and the importance to protect our agro-ecological traditions from exploitation by corporate interests at the expense of the common man.

His wide traveling, and seamlessly mingling with the local people, without any kind of barriers enabled him to become a magnet of values and virtues to all sections of the society – from small scale farmers to IT workers. Even at the time of his passing away in December 2013 near Pattukkottai, he was on a trip to protest the methane extraction project (hydrocarbon projects). His legacy is not just about natural farming, but about building a bottom-up ethos; an ecosystem and lifestyle that is in sync with nature, environment, local livelihoods, and sustainable development.

Tamil Nadu and Natural Farming – Post 2013 and current trends

After his passing away on December 30th, 2013, Dr Nammalvar’s popularity, and his ethos and teachings continue to influence the current and next generations through his writings, his videos, and institutions he had built like Vanagam.

Workshops conducted periodically by Vanagam has attendees from all over Tamil Nadu and from outside Tamil Nadu as well – have influenced thousands of individuals who take on a path in natural farming much more grounded.

New social institutions relating to organic farming and natural farming have also sprung up, and existing social institutions have strengthened.

Dr Nammalvar’s photo can be seen in many organic shops and other places, that he is almost deified in many ways.

Since Tamil Nadu is a technologically advanced state with high network coverage and people of every class with access to social media, we can consider the social media pulse, especially Facebook as a reflection of ground reality. Some of the groups with such high activity are given below:

Organic farm stores and direct farm-to-fork arrangements have also increased in the last decade. After the Jallikattu protests, there has been a renewed interest in native livestock and bull breeding as well, even among the urban youth.

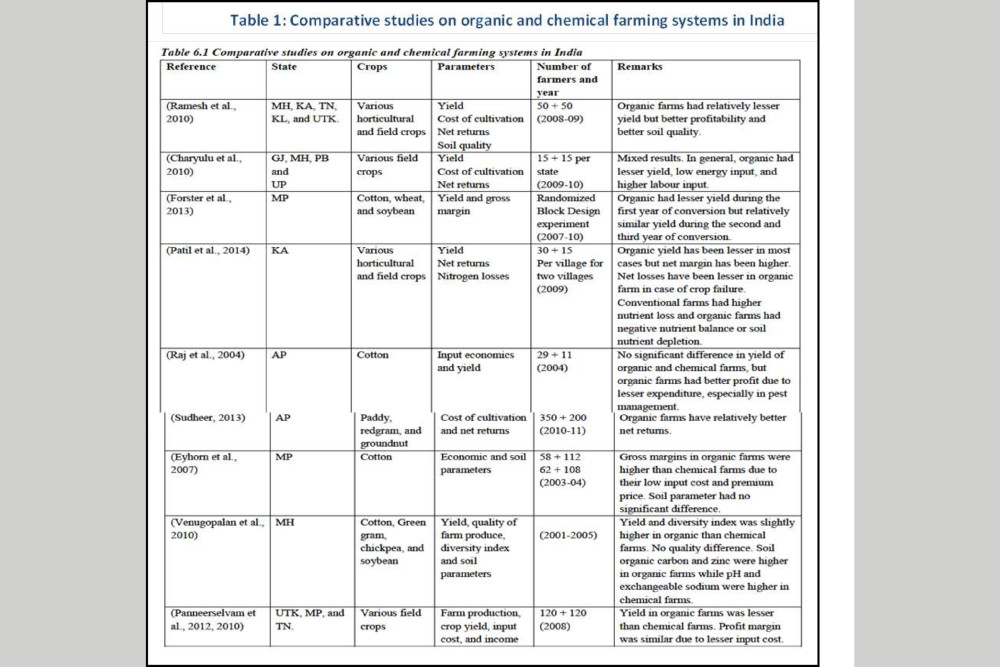

Comparative studies of organic and conventional farming methods suggest a pattern of low input costs, slightly lower yield, but equal or higher net profits for organic farming (Table 2) [19].

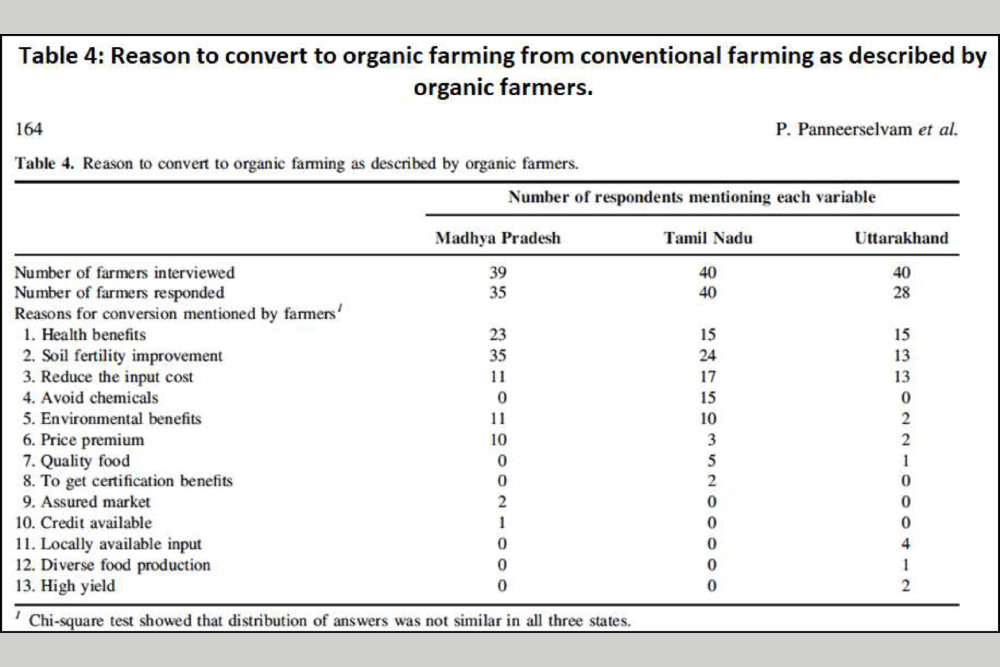

Preliminary studies show that farmers shift to organic farming primarily to perceived benefits such as a healthy soil environment, increased health benefits and safer food (Table 4) [20].

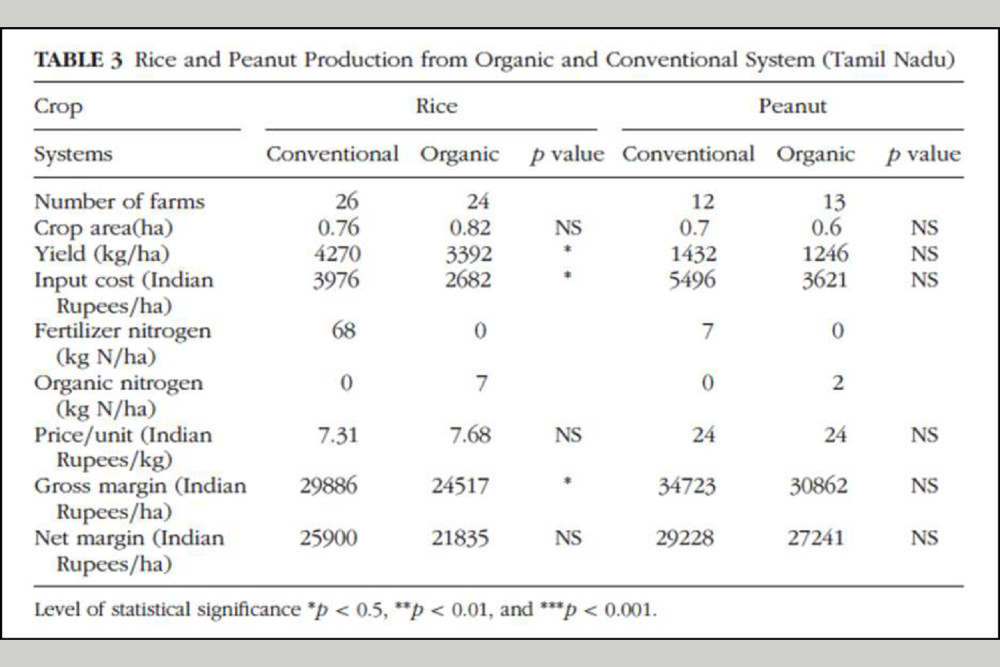

A study with small sample size conducted in Tamil Nadu shows significantly lower input costs for organic farming as compared to conventional farming (Table 3) [21].

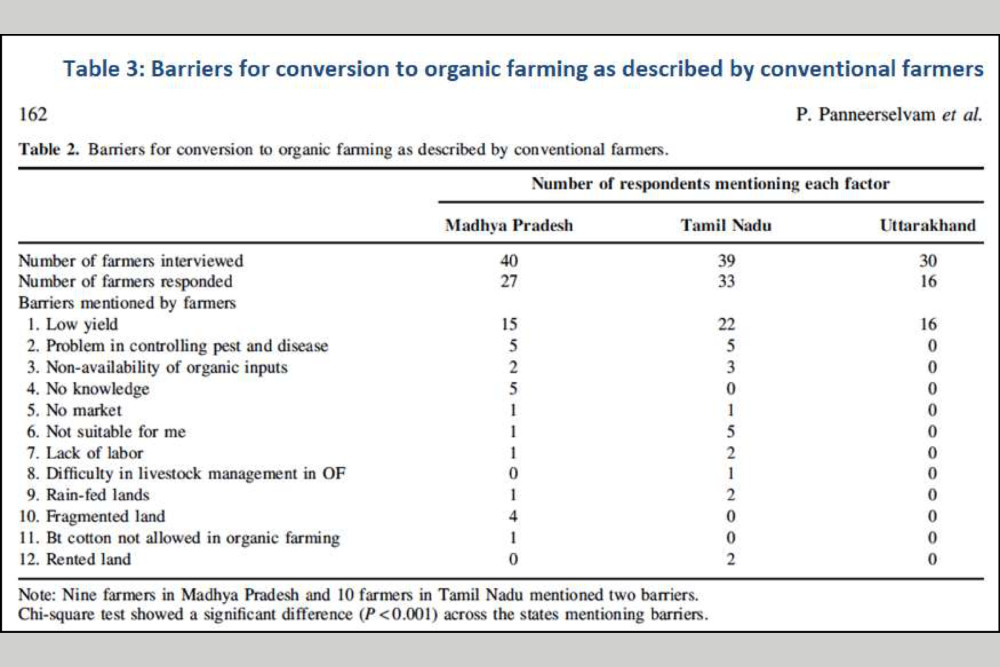

However, the primary barrier cited by conventional farmers of their reluctance to shift to organic farming is – perceived lower yield.

Higher institutional and government support for organic farming – both monetary as well as structural support will help shift this perception as other benefits would outweigh this perceived problem of organic farming.

In Tamil Nadu, as of 2019, according to the Center for Science and Environment (CSE) report, nearly 30,000 hectares of land are under organic certification [22]. This is about 0.6% of the net sown area. However, this would be a gross under-estimate of the actual acreage under organic farming as most organic farmers in Tamil Nadu have existing local market linkages to consumers and operate without the need for certification. Combined with the fact that many organic stores can be found in almost all urbanized parts of the state with their own local farmer networks, one could say that this 0.6% of the net sown area is an underestimate of the actual organic and natural farming acreage in Tamil Nadu.

Conclusion

Globalization as a blanket adoption, as a panacea to highly local issues has created further inequalities, distress and social and economic bereavement in Tamil Nadu, India and internationally as well. The Natural farming movement of Tamil Nadu and its unique success shows that globalization as a be-all and want-all narrative has viable alternatives in grounded local economies that work on local knowledge systems, bioregion based democratic decision making and powerful local bodies. We need to continue to work beyond the global narrative towards a true localization and a prospering agro-economy.

The way forward should be guided by native knowledge systems coupled with decentralised community driven decision making in the fields of agriculture, water body conservation, biodiversity, livestock, food processing, fisheries, forestry with the District, State and Union administration playing a coordinating role.

Rural entrepreneurship empowering youth and women will lead to a strong, locally entrenched economic model which can sell the surplus to the cities. This would solve multifarious problems of job creation, wealth & income disparities, destruction of natural resources, breakdown of social systems. This realignment in policy making is needed to achieve a Gandhian model of village republics founded on JC Kumarappa’s Economy of Permanence.

Important events in the life of Dr.G. Nammalvar and his Books

| Date | Event |

| 6th April 1938 | Born in Elangadu – Thanjavur district, Tamil Nadu |

| 1963 | Graduated from Annamalai University with B.Sc., in Agriculture |

| 1963 | Started working for Agricultural Regional Research Station – Kovilpatti |

| 1969-1979 | Left Kovilpatti Agricultural Regional Research Station. Joined Island of Peace with Dominque Pire. As part of it, worked in Vadakarai village in Kalakad block of Tirunelveli. |

| 1970s | Greatly influenced by Paulo Freire and Vinoba Bhave |

| 1973-1981 | Worked with people belonging to tribal lands of Anjatti and Murattai, Krishnagiri district |

| 1979 | Started Kudumbam |

| 1982-1986 | Developed 20 plus acres of social forest at Ammangkorai, Pudukottai district |

| 1984 | Met and started working with Bernard de-Clerk of Auroville to understand permaculture |

| 1986 | Social forest called Kolinji farm started in Pudukottai |

| 1987 | Attended 4-week training course by ETC Foundation, Netherlands on ecological agriculture |

| 1990 | Founded Network called LEISA (Low External Input and Sustainable Agriculture) |

| 1990 | Started Ecological Research Centre for rain-fed cultivation in Pudukkottai district |

| 1994 | Created people federation for poison free food |

| 1995 | Nominated as Tamil Nadu state co-ordinator for ARISE (Agricultural Renewal in India for Sustainable Environment) |

| 1996 | Seed Conservation, to recover and multiply traditional seed varieties; travelled to many parts of the country to obtain more than 50 varieties of paddy, rare breeds of pulses, vegetable, and green seeds |

| 1998 | Founded Erode Organic farmers movement |

| 2000 | Fought against attempts to patent medicinal properties of Neem along with Vandana Siva |

| 2001 | 500km walk along the Bhavani river basin to “Save Water Reservoir” |

| 2002 | Founded institution called Thamizhina Vaazhviyal Palkalaikazhagam (Tamil Way of Life University) |

| 2005 | Helped farmers in Nagapattinam district after Tsunami. |

| 2005 | Founded Tamil Nadu Organic Farmers Federation |

| 2006 | Left for Indonesia to work on reclaiming farmlands after the Tsunami |

| 2007 | Honoured with a Doctor of Science by Gandhi Gram Rural University, Dindigul |

| 2009 | Founded Vanagam Nammalvar Ecological Foundation |

| 2013 | Launched a Padayatra to rally people against the methane extraction projects in the Delta region of Tamil Nadu |

| 30th December, 2013 | Died near Pattukottai, Tamil Nadu, during the Padayatra |

- Ulavukkum undu Varalaru (Farming has a history too)

- Ennaadudaya Iyarkaye Potri (Hail to my motherland’s nature)

- Ini Ellam Iyarkaiye (Here onward it is Nature)

- Thai Mann (Motherland)

- Thaimanne Vanakkam (Greetings to my motherland)

- Ini Vithaigale Perayutham (Seeds are the weapons of the future)

- Boomiththaye (Mother Earth)

- Vithaiyilirunthu Thulirkkum Maruthal (A change begotten from seeds)

- Vayittrukku Choridal Vendum (Feed the Stomach)

- Noyinai Kondaaduvom (Celebrate Diseases)

- En Vendum Iyarkai Uzhavanmai (Why do we need natural farming?)

References

- TNAU, “12th 5 year plan of Tamil Nadu: Natural Resource Management, 2012.” 2012, [Online]. Available: https://agritech.tnau.ac.in/12th_fiveyearplan_tn.html.

- Statista.com, “India: net sown area Tamil Nadu,” Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/975503/india–net–sown–area–tamil–nadu/ (accessed Dec. 10, 2020).

- M. Chinnadurai, “Situation Analysis of Water Resources in Tamil Nadu,” Int. J. Agric. Sci. ISSN, pp.0975–3710, 2018.

- S. Dharumarajan et al., “Biophysical and socio‐economic causes for increasing fallow land in Tamil Nadu,” Soil Use Manag., vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 487–498, 2017.

- KANCHANAI REEL

- S. Anand, “Nammazhvar ‘converts’ farmers to ‘poison-free’ ways of raising crop | Outlook India Magazine,” https://magazine.outlookindia.com/, Dec. 10, 2001. https://magazine.outlookindia.com/story/nammazhvar–converts–farmers–to–poison–free–ways–of–raising–crop/213981 (accessed Jan. 07, 2021).

- B. Kolappan, “What drives urbanisation in Tamil Nadu – The Hindu,” Jul. 05, 2015. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil–nadu/what–drives–urbanisation–in–tamil– nadu/article7386961.ece (accessed Jan. 07, 2021).

- D. Chronicle, “Tamil Nadu to be most urbanised state by 2030,” Deccan Chronicle, Jul. 04, 2017. https://www.deccanchronicle.com/nation/current–affairs/040717/tamil–nadu–to–be–most–urbanised–state–by–2030.html (accessed Jan. 07, 2021).

- Census of India, “Census of India 2011 – Provisional Population Totals Paper 2, Volume 1 of 2011 Rural – Urban Distribution. Tamil Nadu. Series 34.” 2011, [Online]. Available: https://censusindia.gov.in/2011–prov–results/paper2/data_files/tamilnadu/Tamil%20Nadu_PPT2_Volume1_2011.pdf.

- B. Pandey and K. C. Seto, “Urbanization and agricultural land loss in India: Comparing satellite estimates with census data,” J. Environ. Manage., vol. 148, pp. 53–66, 2015.

- K. Muralidharan, “People on Chennai’s Outskirts Allege Their Water Is Being Stolen to Feed Malls,” The Wire, Jul. 05, 2019. https://thewire.in/environment/thiruvallur–bore–wells–water–tankers–mafia(accessed Jan. 07, 2021).

- C. Anupam, “Hybrid Infestation: The Politics of GM Crops in India,” ritimo, May 14, 2018. https://www.ritimo.org/Hybrid–Infestation–The–Politics–of–GM–Crops–in–India (accessed Jan. 07, 2021).

- K. Akileshwaran and L. Graziadei, “Inclusive growth in Tamil Nadu: The role of political leadershipAnd governance,” Institute for Global Change, Jan. 20, 2020. https://institute.global/advisory/inclusive– growth–tamil–nadu–role–political–leadership–and–governance (accessed Jan. 07, 2021).

- Directorate of Technical Education, Tamil Nadu, “Details of number of engineering colleges, sanctioned strength and students admitted in engineering colleges during the academic years 2006-2013 in Tamil Nadu.” 2014.

- “‘1.60 lakh engineering graduates unemployed,’” The Hindu, Virudhunagar, Jul. 15, 2018.

- “Tamil Nadu continues to produce unemployable engineers | Chennai News – Times of India,” The Times of India, Jan. 30, 2016. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chennai/Tamil–Nadu–continues–to–produce–unemployable–engineers/articleshow/50780273.cms (accessed Jan. 18, 2021).

- B. Paribas, “History of microfinance: small loans, big revolution,” BNP Paribas. https://group.bnpparibas/en/news/history–microfinance–small–loans–big–revolution (accessed Jan. 07, 2021).

- T. N. Content Management System, “Policy Note – 2004-2005, Demand No.5, Chapter -I, Introduction.” 2005, [Online]. Available: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwjE_6Da6InuAhXm6nMBHQ7IBUQQFjABegQICBAC&url=http%3A%2F%2Fcms.tn.gov.in%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fdocuments%2FAgriculture%2520Department.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3vy3y3jm16V1qqjdNj43yJ.

- S. Muthuprakash and O. Damani, “Development and Application of a Farm Assessment Index (FAI) – Towards a Holistic Comparison of Organic and Chemical Farming.” Nov. 2018, [Online]. Available: https://www.kisanswaraj.in/category/reports/.

- P. Panneerselvam, N. Halberg, M. Vaarst, and J. E. Hermansen, “Indian farmers’ experience with and perceptions of organic farming,” Renew. Agric. Food Syst., vol. 27, no. 2, pp. 157–169, 2012.

- P. Panneerselvam, J. E. Hermansen, and N. Halberg, “Food security of small holding farmers: Comparing organic and conventional systems in India,” J. Sustain. Agric., vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 48–68, 2010.

- Center for Science and Environment, “State of Organic and Natural Farming in India.” 2020.