Introduction

This study explores, and investigates the status of implementation of Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014 in India’s largest, and richest metropolitan municipality – Municipal Corporation of Greater Mumbai(MCGM) also commonly known as Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC). The study draws mainly from Center for Civil Society’s excellent reports on the status of overall implementation of the act in the country and as well as CCS’s Narang’s deep dive report in the case of Mumbai. Likewise, study also briefly looks into Mumbai history with regards to its development, history of the informal sector, and importantly, its street vendors unions roles in historical and ongoing legal fights and struggle for collective rights of its members.

Mumbai and Its Development

Mumbai, originally a group of seven marshy islands on the west coast of India and a fishing village until the 16th century, was ceded by the Moguls to the Portuguese in the 1630s. Later the King of England leased it to the East India Company. It developed as an important port, used by the British for more than two centuries. The history of the creation of wealth in Mumbai has essentially been a product of investment by merchant-capitalists, professional expertise, and abundant cheap labour of migrants from within the region or from far-off areas. The handling of cargo by its seaport, competitive textile industry, and finance and trade set the tone for such a development.

The surplus capital generated was partly reinvested in chemical and allied industries, and the rest mainly diverted to fixed assets like real estate and gold trade or converted into the black money. The creation of wealth thus led to the darker side of development, manifesting in unethical business and the emergence of the underworld. The unskilled or skilled migrant 35

workers were poorly paid and settled either in dingy dwellings provided by the employers or in slum structures through informal means (mainly with the help of slumlords).

At the time of ‘opening up’ of Indian economy to global markets (in 1991-92), Mumbai showed symptoms of a declining megapolis for reasons like (a) over-burdened land-use due to population explosion (due to large in-migration and natural growth), (b) crumbling infrastructure (c) aging housing stock in the main city, (d) over 45 per cent of the population living in dehumanised conditions in over 2,000 slum settlements, (e) depleting public resources for any significant improvement, (f) social housing schemes of government departments marred by scarcity of land for mass housing and inefficient and corrupt practices, (g) virtual seize of the city by the builder mafia and land sharks, and above all (h) the decline in manufacturing activity and rapidly growing informal economy in the city. (Sharma 2010).

The pace of migration of rural poor to the city increased manifold in the 1970s and onwards, with the result of proliferation of slum settlements all around. These slums were sandwiched between the commercial areas and regular housing settlements of the middle and upper classes. Such a mixed use of landscape of the city became symbolic of the chimneys, ware-houses, and godowns integrated with the housing clusters of various classes of population (Shaban 2008). As the city grew urban development plans tried to catch up through mega debt financed projects with main focus on Infrastructure constructions, housing and settlements. In and around these mega projects, skyscrapers, commercial malls the slum grew at a tremendous rate. According to the 2011 census, Mumbai had 12 million population with the biggest share of slum dwellers among the big metro cities, with 42 percent of its population residing in slums and this share is only going to increase in decades to come. Some estimate it to be 65% of the total population by 2030. These slums occupy just 7% of Mumbai’s total land area. According to a UN World Urbanization Prospects report Mumbai’s population will reach close to 25 million by 2030.

Urbanisation in India has been termed a ‘messy and hidden process’, with urban governance institutions finding themselves unable to cope with the steady influx of rural populations to urban regions for work. (Ellis and Roberts 2016, 2). There always has been an uphill battle for the governance and administration institutions to plan, upgrade and manage big metropolitan areas especially when there is regular movement of people and goods in and out of the city like Mumbai.

Informal Sector in Mumbai

Large part of the fuel for economic growth has been the informal sector that is supporting the majority of the population. The underbelly of any modern city particularly in a developing country has been its informal sector.

According to ILO definition “The informal sector is broadly characterised as consisting of units engaged in the production of goods or services with the primary objective of generating employment and incomes to the persons concerned. These units typically operate at a low level of organisation, with little or no division between labour and capital as factors of production and on a small scale. Labour relations – where they exist – are based mostly on casual employment, kinship or personal and social relations rather than contractual arrangements with formal guarantees.”

The informal sector represents an important part of the economy, and certainly of the labour market, in many countries and plays a major role in employment creation, production and income generation. In countries with high rates of population growth or urbanization, the informal sector tends to absorb most of the expanding labour force in the urban areas. Informal employment offers a necessary survival strategy in countries that lack social safety nets, such as unemployment insurance, or where wages and pensions are low, especially in the public sector. In these situations, indicators such as the unemployment rate and time-related underemployment are not sufficient to describe the labour market completely. (International Labour Organization (ILO) 1993)

A broader conceptualization of what is formal and informal sector especially in developing countries have kept academicians busy. Empirical findings from scholar (Bhowmik 2005, 22- 23) studying different socioeconomic arrangements in developing countries like India and parts of Latin America argue for a more inclusive understanding of urban informality (i.e. as part of the formal, regulated space) in an urban city’s ecosystem which includes those working as part of what can be seen as the informal/unregulated space. In fact, on closely observing the businesses of those categorized as ‘informal workers’ one can see an inter-twined, more complex relationship between the ‘formal’ and ‘informal’ aspects of commercial exchanges taking place (Martínez, Rennie, and Estrada 2017, 34-43) (Sekhani, Mohan, and Medipally 2019, 120-129).

The distinct features of a city like Mumbai is the tens of lakhs of people staying in slums amongst sporadic towers here and there. Traditionally, slums used to be places where low income people stay but with the influx of migrants and need for low housing settlements these slum areas became overcrowded with spaces divided into smaller and smaller areas. Slums can be understood as an outcome of the industrialisation process and urban growth. In these slums, people adopted and even perfected to an extent strategies to survive in the city; this is one of the draws for the people to continue to exist in a tough and dilapidated habitat. Street vending is one of those strategies for livelihood that lakhs of slum dwellers have adopted for decades. street vending not only provides livelihood opportunities for those who have the least in terms of capacity, agencies, and resources but also in large part what tens of lakhs of low income and some middle class families depends on as their sources of quick, cheap, daily, regular, and essential items to survive and exist in a otherwise expensive city. However, street vending as a service and people engaged in it has complicated and complex relationships with society at large.

As illustrated by Jha “Despite street vending being one of the oldest forms of retail in the country, the urban laws of independent India still neglect the activity and its practitioners. City administrators continue to regard hawking as illegal. There are sections of the public who feel that hawkers encroach on spaces meant for civic use, and others simply consider them as eyesores. Even those who may be buying goods from vendors, would like for them to be more obscure. Clearing streets, footpaths and transport terminals of vendors and hawkers, and confiscating their goods, is a daily municipal activity. For their part, the street vendors continue to claim their space in the cities to earn their living. In a cat-and-mouse game, local officials ignore hawkers when convenient and tighten the rules on them when exigencies have demanded preventive action.

This has served a dual purpose: some underhand money goes to the administration for turning a blind eye, and the street vendors get to conduct their business too. With time, hawkers found able allies and protectors among local councillors who objected to their eviction and instead promoted their proliferation. Hawkers returned the favour by turning into loyal voters and political workers. A complex calculus emerged: hawking was bad under the law, but the law did not find any takers. While hawkers dared it and breached it, buyers ignored it and abetted its breach. Local politicians benefited as it helped perpetuate their career, and administrators ignored the implementation of the law, tempering private profit with local exigency. Consequently, street hawking continued to ‘thrive’ illegally in every Indian city”. (Jha 2018)

History of the Fight for Rights of Street Vendors

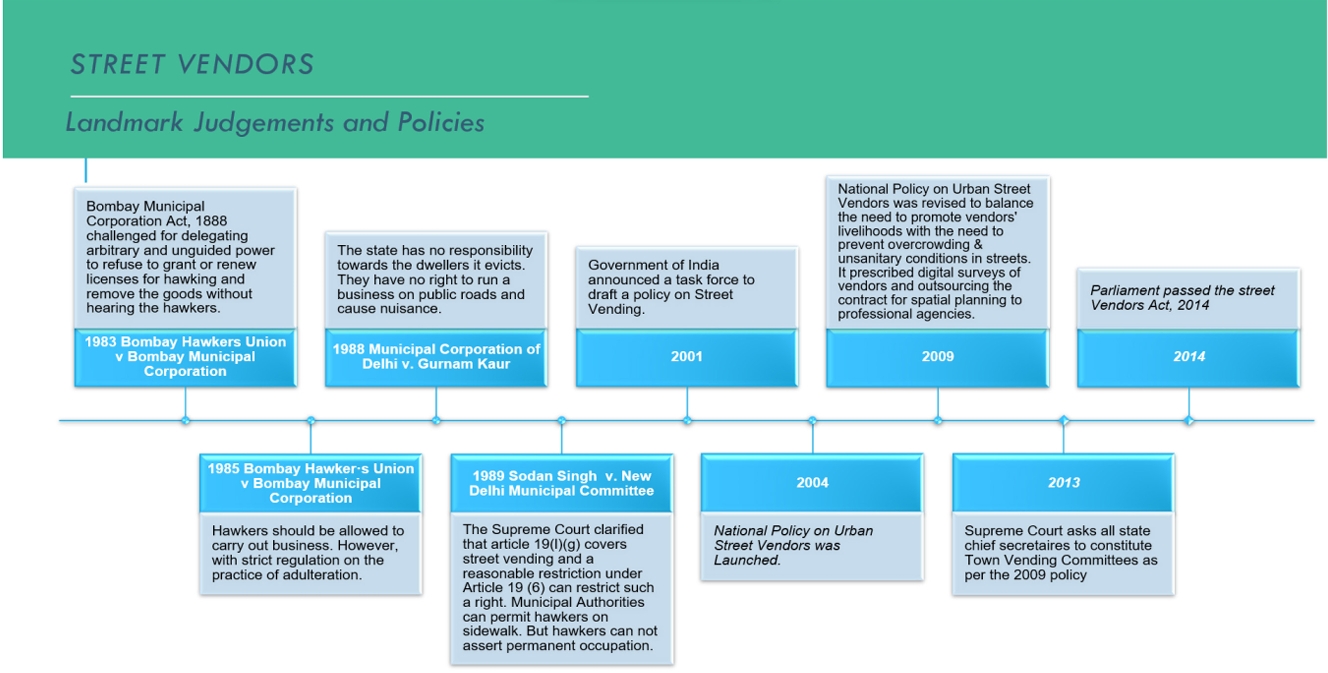

Roughly 2.5% of India’s population is engaged in street vending (Bhowmik 2003, 1543 -1546). Yet, the road to 2014 acts and beyond have been and is full of struggle and fights for self-determination and legal recognition for the street vendors as shown in the graph below.

Back in 1983 hawkers union filed a writ petition before the Supreme Court that culminated in judgement in 1985 by the court to direct the Municipal Commissioner to demarcate zoning in consultation with the BMC, and to frame the final Scheme based on the Court’s directions and observations. The Supreme Court empowered the Municipal Commissioner to extend the no-street vending zones in the interest of public health, sanitation, safety and public convenience.

In 2009, National Policy on Urban Street Vendors was adopted. The Policy prescribed digital surveys of vendors and outsourcing the contract for survey and spatial planning to professional agencies for spatial planning.

In 2013 as per the 2009 Policy, BMC Commissioner constituted a 30-member TVC under his chairmanship In 2014, The Parliament of India enacted the Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Street Vending) Act, 2014.

Salient Features of the Street Vendors Act 2014

Although municipal zoning and regulation of vending falls under the State List, the standing a committee on the Street Vendors Bill recognised that Parliament may legislate on the rights and obligations of street vendors under entries 20, 23 and 24 of the Concurrent List (Bedi 2013). Historically, the issue of public spaces & its development, and public safety versus street vendors’ right to livelihood has been the core of many legal issues. Even though the act was passed in 2014 the implementation of it in letter and spirit has been tough in degrees from state to state. The matter of street vendors’ livelihood comes under concurrent list. Hence the Act delegates the power to the state to make legislation It lays out the statutory contours within which the local institutions built by state governments may evolve. To meet the letter and spirit of the Act, state governments ought to:

- Formulate subordinate legislation that lays out an appropriate framework for guiding institutional mechanisms and processes;

- Establish institutional mechanisms (such as Town Vending Committees and Grievance Redressal Committees) and execute processes (such as vendor surveys and demarcation of vending zones). (Bedi and Narang 2020, 4)

Hence, each state had to make State act, rules and schemes which in turn will support by-laws as per the section (37) of the national Act. As per the Act, once the framework is established, the minimum institutions and processes that state governments ought to put in place to protect the interests of vendors include:

- Constituting participatory Town Vending Committees (TVCs): The Act instills accountability at the local level by necessitating the formation of local governance bodies called TVCs. To encourage participatory decision making and recognise the voice of vendors, the Act requires 40% of TVC members to be vendors. Civil society participants (such as members from non-government or community-based organisations) must constitute 10% of the total strength.

- Surveying street vendors, issuing certificates of vending and distributing identity cards: TVCs are responsible for enumerating vendors in their jurisdiction at least once every five years. Section 3(3) of the Act prohibits any eviction before all existing vendors are enumerated. Once the enumeration is complete, TVCs must issue certificates of vending to the identified vendors (based on criteria laid down in the Act and state schemes). Following this, all vendors holding certificates of vending must be given identity cards.

- Formulating the city street vending plan and demarcating vending zones: Section 21 of the Act requires each local authority to formulate a vending plan (once in every five years), after consulting the TVC. The plan should lay down criteria for earmarking ‘no-vending’, ‘restricted’ and ‘restriction-free’ vending zones and give priority to natural markets. These norms must be in consonance with the principles for demarcation mentioned in the First Schedule of the Act.

- Constituting Grievance Redressal Committees: Section 20 of the Act recommends the local authority to form one or more Grievance Redressal and Dispute Resolution Committees for addressing vendor disputes and grievances. It prohibits members of the local authority or state governments from being a part of this committee. (Bedi and Narang 2020, 5)

Implementation of the Act

In 2014, The 2013 Mumbai TVC passed a resolution to form 241 teams for conducting a survey of the vendors. (However, BMC did not hire any professional agency to undertake a survey. Moreover, the survey should have been in a census-like fashion. Instead, BMC merely distributed forms and asked the vendors to submit the filled form later, along with other documents. It was an application-based registration drive. When the BMC sent letters to vendors asking them to submit documents in time, many letters came back undelivered. This is precisely what a census-like survey would have avoided.

The BMC issued only 1,28,443 forms to vendors and 99,435 vendors submitted the forms. Vendors needed to submit a birth certificate, a domicile certificate, proof of working as a vendor (any fine/receipt issued by the police/ court/BMC before 1 May 2014) and an undertaking (hamipatra) of having vending as their only source of livelihood. On Jul-Aug 2018: TVCs completed verifying 96,655 applications of the total 99,435 applicants; remaining 2,780 applicants are pending verification. The TVC found only 23,265 applications eligible. BMC asked for a domicile certificate among other documents from the applicants (Narang 2020)

The short of long story of the status of implementation of the Act in Mumbai and overall in Maharashtra state is abysmal. Ever since the Center of Civil Society’s publishing annual report on progress on the implementation of the Act state wise, Maharashtra has been at the bottom of the list. In their 2020 report Maharashtra is at third spot from bottom barely above Uttarakhand and Assam. Implementation of the act can be looked at from two stages first being de jure implementation and second is de facto implementation. Maharashtra implementation efforts in these two stages have faced setbacks from the beginning.

In de jure implementation the state was supposed to implement state level act, rules and schemes. As mentioned before, in 2013 BMC constituted a 30 member TVC based on the 2009 National Policy on Urban Street Vendors. This is what Mr. Macancy Dabre of National Hawkers Union points out as the source of the initial problem. According to him, the Maharashtra government should have involved street vendors in the discussion of acts, schemes, and TVC formation. But instead certain clauses in the rules namely – rule R22(10) empowers the Municipal Commissioner or the Chief Officer to reject a proposal “passed in Town Vending Committee on majority of votes or voice of vote” and similarly, rule 22(11) empowers the Government of Maharashtra to “recall the proceedings of the Town Vending Committee and revoke the proposals passed” if the proposal is not in accordance with certain local laws. This is repugnant to the centred act.

As per the Constitution of India in the matter of legislations on subjects like street vendors livelihood which is in concurrent list the article 246(2) – gives power to two legislatures(Center and State), and during a conflict that can arise between laws passed on the same subject by the two legislatures Articles 254(1) states that the law made by Parliament, “whether passed before or after the law made by the Legislature of such State, or, as the case may be, the existing law, shall prevail and the law made by the Legislature of the State shall, to the extent of the repugnancy, be void.” Then on the 9 January 2017 after 2 and half years State formulated a scheme for the whole of state without consulting the local authorities and local TVCs.

On the same day, the State also brought out another government resolution entitled “Scheme enforcement related information” allowing local authorities to constitute TVCs without any representation of street vendors. Another rule going against spirits and the letter of the center’s law. Moreover, in the city Mumbai TVC was formed before the state even enacted the act or schemes. All these were disputed in Azad Hawkers Union v. Union of India MANU/MH/2574/2017 in which on 1 November 2017 the Bombay High Court held: (1) the scheme dated 9.01.2017 could not be regarded as the statutory scheme because the Government did not consult the local authorities and TVCs for framing the scheme, as per the Act; (2) BMC-conducted survey of 2014 can be considered to be the first survey under section 3 of the Street Vendors Act, 2014 and elections can be held based on that survey; (3) Government resolution dated 9.01.2017 allowing the local authorities to constitute TVCs without the representation of street vendors, was bad in law.

Till now, no new or amended scheme has been enacted, hence, no local bylaws have been passed and no elections have taken place. The delays, inactions, conflicting rules and subsequent challenges to the rules, schemes stalled the first stage of de jure implementation of Act. Meanwhile, all these years BMC didn’t start the process of new surveys and in fact 42

operationalized TVCs, a central TVC, and 7 zonal TVCs that met a couple of times over the last 7 years. Few street vendors’ union members, and NGOs are represented in these central TVC and zonal TVCs. Their selection was done based on a lucky draw method. It has been 7 years without an election. The Street Vendors Act 2014 states elections for new street vendors representations in TVC at least every 5 years. Moreover, the 23 thousands Street vendors that BMC recognised in the 2013 survey are yet to receive certificates or IDs. In fact, the reality for a normal street vendor is the same as before the act was enacted 7 years back.

References

- Bedi, Jayana, and Prashant Narang. 2020. Progress Report 2020: Implementing the Street Vendors Act. N.p.: Center for Civil Society.

- Bhowmik, Sharit K. 2003. “National Policy for Street Vendors.” Economic and Political Weekly 38, no. 16 (April): 1543-1546.

- Bhowmik, S. K. 2005. “Street vendors in Asia: A review.” Economic and Political Weekly 40:22–23.

- Ellis, P., and M. Roberts. 2016. Leveraging Urbanization in South Asia : Managing Spatial Transformation for Prosperity and Livability. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- International Labour Organization (ILO). 1993. Resolutions Concerning Statistics of Employment in the Informal Sector Adopted by the 15th International Conference of Labour Statisticians. https://stats.oecd.org/glossary/detail.asp?ID=1350.

- Jha, Ramanath. 2018. “Strengthening Urban India’s Informal Economy: The Case of Street Vending.” ORF ISSUE BRIEF, no. 249 (July).

- Martínez, L., J. Rennie, and D. Estrada. 2017. “The urban informal economy: Street vendors in Cali, Colombia.” Cities 66 (June): 34-43.

- Narang, Prashant. 2020. Street Vendors Act 2014 Enumerating Street Vendors in Mumbai, Maharashtra. New Delhi, India: Center for Civil Society.

- Sekhani, Richa, Deepanshu Mohan, and Sanjana Medipally. 2019. “Street vending in urban ‘informal’ markets: Reflections from case-studies of street vendors in Delhi (India) and Phnom Penh City (Cambodia).” Cities 89:120-129.

- Shaban, A. 2008. Politics of violence and production of urban spaces in Mumbai, Paper presented at ‘Urban Research Centre Seminar’, London School of Economics.

- Sharma, R. N. 2010. “Mega Transformation of Mumbai: Deepening Enclave Urbanism.” Sociological Bulletin 59 (1 (January-April 2010)): 69 – 91. https://www.jstor.org/ stable/23620846.