The challenges facing the new government, the country, and its people are immense. After 74 years as a democratic republic, the rights guaranteed by the Constitution of India are still not a reality for the vast majority.

Approximately 70% of India’s population, nearly 1 billion people, live in sub-human conditions. Pervasive poverty, chronic malnutrition, hunger, disease, lack of water, food, shelter, sanitation, quality education, health services, and social security are the chief causes of misery and destitution for the masses. It is ironic that in independent India, the overwhelming majority of people struggle to eke out a bare minimum livelihood despite the Constitution standing in their name.

The Growth Model

The root cause of mass deprivation and massive ecological devastation is the growth model pursued by successive governments (both Union and state) of varied ideological hues.

The main pillars of this paradigm are industrialization and urbanization. Ideologically, Russian and Chinese growth models may seem diametrically opposite to those of North America and Western Europe in terms of state or market control of capital.

However, in terms of technology, production processes, consumption patterns, and lifestyles, they are similar. Both systems are resource-squandering and ecologically disastrous, viewing nature and people as commodities for super-profits and power control. Tragically, the ruling elite worldwide perpetuate this status quo.

Third world countries, including India, have followed the same growth model, albeit with a different mix of the two. Thus, the costs and consequences of capitalism and socialism are equally fatal. There is an urgent need to move beyond these “isms,” particularly fossil fuels causing climate change. Thinkers like Ruskin, Thoreau, Tolstoy, and Gandhi out rightly rejected growth models based on greed, consumerism, militarism, violence, subjugation, genocide, and ecocide.

According to them and many other thinkers, the dominant growth model is anti-nature and anti-toiling people. The growth mania for profit and resource control has pushed the world to the brink of disaster. The military- industrial complexes and many transnational corporations are threats to the planet and people.

Today, the cumulative consequence of the technologically over-dominant growth model is “jobless growth.” Above all, it means alienation from nature and society. Thus, it is not only jobless but also “rootless, ruthless, voiceless, and futureless,” as the Human Development Report warned.

GDP is not Well-being

In view of the aforesaid global and Indian reality, the repeated rhetoric of making India the third-largest economy in the world is inane, if not altogether insane. In fact, India is already the third-largest global economy in terms of purchasing power parity. But what does this mean to the 1 billion people who are bearing the brunt of subhuman existence?

It is necessary to look into some recent facts relevant to the well-being of the people. India ranks 134th in the Human Development Index of 191 countries, ll4th in the Hunger Index covering 125 countries, and at the bottom (l80th) in the Environment Performance Index among 180 countries.

In Air and Water Quality Indices, India’s ranking is equally dismal. This means the GDP of a country is not a meaningful indicator of well-being, as emphasized by Nobel Laureates Joseph Stiglitz and Amartya Sen. In short, “more of the same” (mega projects, GDP, growth rate) is not the appropriate approach to tackle the problem of mass deprivation and massive ecological destruction perpetrated in the name of “national development.”

The pertinent question is: growth of what? Growth for whom? Fortunately, there are alternatives which are cheaper, quicker, and safer. Of course, they should not be deployed as a mere techno-fix but adapted to societal needs with techniques appropriate to the agro-climatic and demographic conditions, and active participation of the people.

The choice of production and consumption should be guided by care and conservation of ecosystems to provide for the needs of present and future generations.

Low- carbon lifestyles should be the guiding principles of production and consumption of goods and services. Instead of supply, abundance, and dumping, it should be careful demand management, meeting the needs of all and the greed of none.

Agenda for Action

Considering the current Indian scenario, some broad measures are proposed for just, equitable, and sustainable development of India. Let us begin with the resources: natural, human, technological, and fiscal. India’s natural endowments, including land, water, flora, fauna, and biodiversity, are substantial.

However, due to neglect and unsustainable distorted resource-use patterns, they have declined, degraded, and been devastated. Moreover, there has been pervasive plunder by colonial rulers to serve their interests. Post- 1947 national governments persisted on the same path to industrialize and create infrastructure.

Today, the paramount task is to stop the further decline and devastation of these precious resources and harness them scientifically to meet the basic needs of the people. Interestingly, the Constitution of India enjoins this as the duty of the State as well as the citizens.

Land (inclusive of all natural resources) and labour (manual and skilled) is the pivot of the production of all goods and services. Ecosystem services are also crucial. Therefore, public policies should address natural and human resources holistically.

Technology, capital, and enterprise should supplement, not supplant, these resources to ensure equity and sustainability. For this, legislative and policy reforms are proposed, including raising the tax-to-GDP ratio to 30%, as seen in many OECD and developing countries. The additional revenue should be earmarked for education, health, and employment.

Land is the basic source of sustenance for all living beings. Currently, 46% of India’s workforce is engaged in the agriculture sector. Land should legitimately be owned by those who physically toil on it. “Land to the tiller” was a prime plank of our freedom struggle, and land reform laws were enacted soon after Independence to redeem this promise.

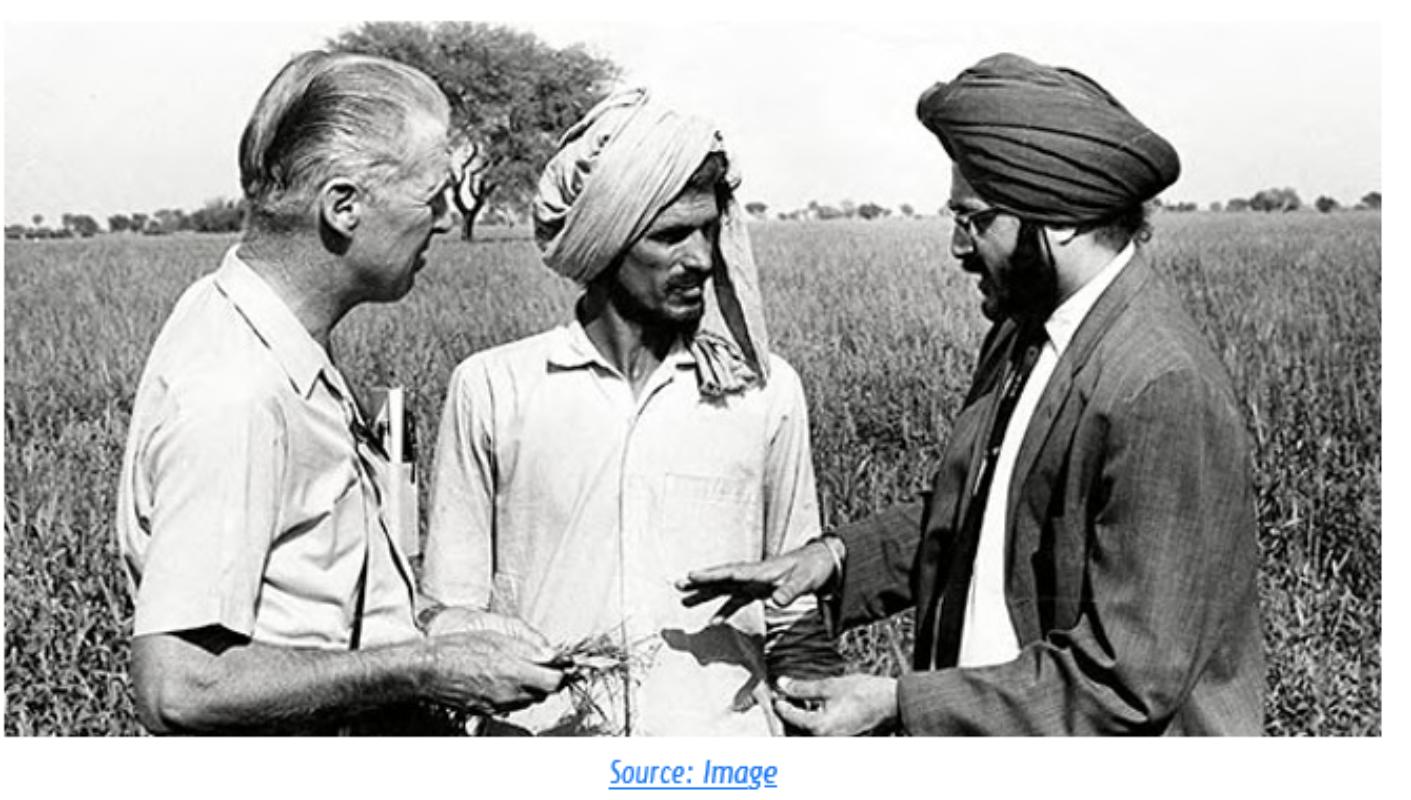

However, the latest data shows that the top 2% of landholders own 26% of the total cultivated land in India. Nearly half of the agricultural land is owned and controlled by 7% of the landed gentry, while 55% of the agricultural workforce is landless. The Green Revolution of the 1960s diverted policymakers’ focus from institutional reforms to a technocratic strategy, providing state support to big landowners with resources to invest in costly agricultural inputs and mechanization of farms.

The consequence of this chemical and industrial farming is the pollution and poisoning of the entire food chain, adversely impacting human, animal, and soil health. To escape this trap, we must provide incentives for organic agriculture, which is labour-intensive and environmentally benign. For ecologically sound farming, the land must belong to those who labour on it. India needs a new agrarian revolution—Krishikranti—to provide livelihoods, nutritious food, and good health to everyone.

To tackle unemployment, expanding, extending, and streamlining public employment guarantees through MGNREGA is crucial. It proved its efficacy during the COVID-19 pandemic. At its peak, over 100 million people were provided work and livelihoods. This must be extended to urban areas, designed to provide work to 50 million urban residents. In brief, a work guarantee of 240 days a year at a minimum wage of Rs 500 per day should be made available to 100 million rural and 50 million urban workers.

This would ensure an income of Rs 10,000 per month for every family opting for work. This guaranteed livelihood would also build massive infrastructure like watersheds and social sector amenities like schools, hospitals, and old age homes. It can effectively drought-proof and flood-control India, providing water to every farmer and other producers of basic goods and services.

Dovetailing natural and human resources with public works is key to providing basics to all. This should be a program to build India in line with Gandhi and Ambedkar’s vision and values, creating productive and not parasitic employment by generating durable assets.

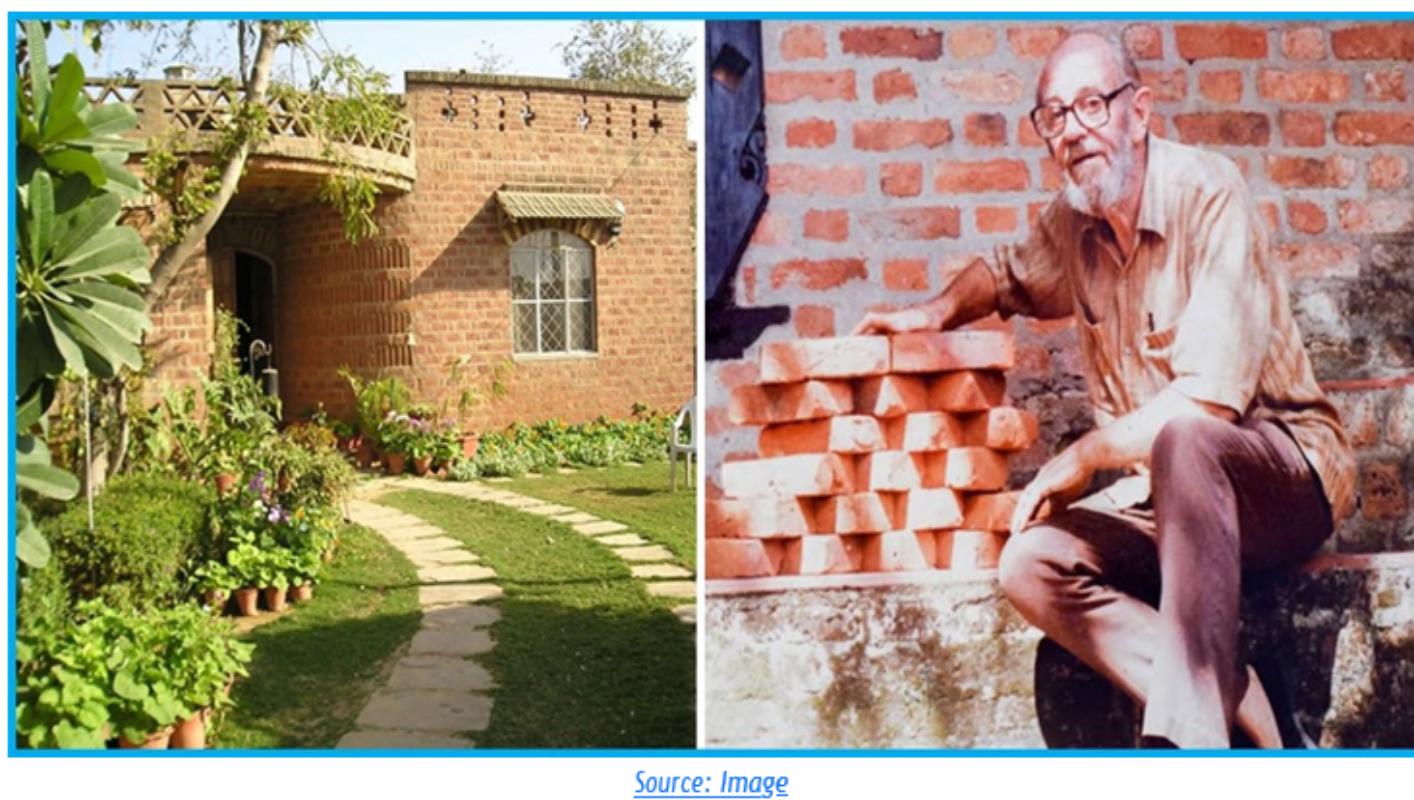

The construction sector, employing millions, is second only to agriculture. It provides work to 14% of India’s workforce, often under inhuman conditions with low wages and no security or safety. Although laws exist to improve these conditions, the nexus between builders and public functionaries perpetuates exploitation. An urgent overhaul of construction design and materials is needed.

Experts like Laurie Baker suggest structures using maximum local materials and skills with a focus on energy efficiency. Materials like steel, cement, plastic, and glass should be minimized or avoided. This approach is cost- effective and ecologically benign. The construction sector, rife with manipulation, fraud, and corruption, needs thorough investigation, regulation, and reform through a high-level commission on construction, covering all infrastructural, industrial, commercial, and residential housing projects.

Additionally, a permanent “Ecology Commission” should be established to monitor activities and suggest specific designs for constructions across categories like personal dwellings, public utilities, industrial projects, and other mega-projects.

The commission should have statutory powers to monitor, supervise, and protect all natural resources and ecosystems in India. The ecological footprints of all activities should be measured, progressively taxed, and emissions phased out. The energy and transport sectors require total overhaul, with drastic reforms needed in the automobile sector. The main objective is to phase out all fossil fuels by 2030.

Finally, India’s policy of modernization, industrialization, and urbanization has been highly centralized and capital-intensive, incongruous with the country’s factor endowment. Mahatma Gandhi vehemently opposed this paradigm, advocating an “ecological worldview” rooted in social ethics and the relationship between humans and nature.

He famously categorized it as need versus greed. Globalized greed has created climate catastrophes posing existential threats. India’s and the world’s growth trajectory requires an alternative approach to economics and politics. A Gandhian pathway can bail us out from the current crisis. The world is on the verge of crossing the

1.5°C threshold stipulated by the Paris Agreement, a frightening scenario. The need of the hour is to live in harmony with nature, requiring radical reforms in our educational and health systems relevant to the 21st century. T

he economic, industrial, and educational systems of the 20th century are inadequate and counterproductive to meeting our current challenges. We have the necessary resources; what we need is a holistic vision and political will.

Dr H. M. Desarda is an ecological economist and a former member of the Maharashtra State Planning Board.