MSMEs in Punjab

The MSME sector in Punjab is characterised by a larger proportion of small and medium enterprises. There is relatively low level of enterprises at the micro scale. For convenience, the SMEs can be divided into two categories. One, which were doing well until as recently as March 2020 and were impacted by the COVID- 19 pandemic. And second, those which have been historically done better and have either reduced in size or closed down over the last few years, largely due to losing the competitive advantage to either domestic or foreign producers. This section concerns largely with the former. Towards the end, it also highlights opportunities to revive and/or create new MSME clusters.

Table 1: Challenges and Suggestions for MSMEs in Punjab

| Challenge | Way Forward | ||

| 1. | Fall in demand: This has emanated from the pandemic and subsequent restrictions. Even though manufacturing units in Punjab have started operating, at around 40% capacity utilisation at the most, the demand has yet to pick up for these units to be fully operational. | The state government has very limited role to play in revival of demand, more so for export oriented units. Even for domestic demand is concerned, ensuring cash in hand of consumers will require action by the Central Government. The role of the State Government is efficient implementation of Centrally Sponsored Schemes including DBT, PDS, MGNREAGA, PMAY etc. so that these reach the people and some demand gets stimulated. | |

| 2. | Working Capital: The disruption in operations and subsequent losses compounded with outstanding loan payments have seriously impacted working capital availability in the sector. | The uptake of the Central government’s Emergency Credit Line Guarantee Scheme (ECLGS) and disbursement rate could be improved. Currently around 30% of eligible borrowers have opted out and of those sanctioned (~95%), disbursal have been to only about 44% (July 2020 data). As per the Dept. of Industries and Commerce, the overall amount of loan under ECLGS for 1.65 lakh eligible MSMEs in the state has worked out to Rs 4845 crore. The combined losses of MSMEs for lockdown period till May 2020 were estimated at Rs 4169 cr. | |

Opportunities for old/ new MSME units or clusters

In context of new national push for self reliance, coupled with strategic intentions to replace China as source of imports, the old clusters in Punjab which originally decayed in tandem with increase in competitive imports, largely from China can be revived. The major import categories are Machinery and Mechanical appliance, Chemical Products, Base materials and articles of base materials, and textiles and textile articles, which accounted for 47%, 19%, 9% and 4.3 % of total imports.

In 2017, out of 404 MSMEs in Mandi Gobindgarh Steel rerolling cluster, only 200 rolling mills were operational. It had risen to 250 in 2019 and the production of moulded steel doubled from 1.5 lakh tonnes per month to 3 lakh tonnes a month in the same period (Indian Express). With Mandi Gobindgarh Steel Re-rolling cluster showed signs of revival, along with Machine and metal working clusters in Ludhiana, and advance machining cluster in Mohali, the production of machinery and machine appliances can be taken up. This would require investment in upgrading technology deployed, research and development, with a focus on product development addressing local needs.

With application of semiconductors in new categories of uses, especially high voltage applications such as electric vehicles, solar energy, data centres and 5G base stations, there will be an upsurge in the demand for Silicon Carbide (SiC) based semiconductors. These are better than traditional Silicon based semiconductors in high voltage operation, heat resistance, and reduced size. The Rajiv Gandhi Institute for Contemporary Studies carried out a potentiality study for SiC based semiconductor manufacturing in India1. Given that the Semiconductor Laboratory (SCL) already exists in Mohali, a SiC devices based manufacturing ecosystem in India can be established in Mohali.

Urban Housing in Punjab with focus on Industrial Workers

“The Task Force on Urban Housing Shortage in Punjab” in 2012 estimated housing shortage at 0.39 million dwelling units. According to the National Building Organisation 2015, Punjab had 1.46 million people in slums (2 per cent of India’s total slum population). Five cities that have high share of slum population, have been taken up under the PM Awas Yojana — Ludhiana, Jalandhar, Bathinda, Patiala and Amritsar.

Ludhiana has 209 slum pockets and the slum population growth rate is 25 per cent in contrast to city’s annual population growth of 8.75 per cent. Jalandhar has 97 slums that have 25 per cent of city’s population. In Bathinda, slum population is 18.68 per cent of the total urban population. In Amritsar 28 slums has 36 per cent of the city’s urban population. This indicates explosive demand for proper housing.”2

Punjab is perhaps one of the very few states, where urban poverty is greater than rural poverty. This largely comprises of migrant labourers from eastern states, who come to Punjab in search of livelihoods, and is concentrated in the biggest cities of Punjab. Faced with untenable living conditions, it is going to be a challenge for the state to obtain and retain manual workers to support its urban economy in the future.

To kickstart the urban economy after the slump due to COVID pandemic, and to retain manual labour in the long run it is imperative to provide affordable and tenable rental housing as close to the source of livelihood.

The master plans of all major cities in Punjab have earmarked areas for residential and industrial activity. The areas of current and planned industrial activity have scattered residential areas within, which are villages lying in the industrial zones. The first target for construction of affordable rental housing could be these areas. Alternatively, patches of non-culturable wastelands around these areas can be identified.

As to financing, process of land acquisition can be born by the government, and cost of construction can be financed by the private builders. The investments can also be made by cooperatives of the original owners of these lands, who stand to lose their lands to residential purposes. (This model is known as the Magarpatta model, which was tried very successfully in Pune).3 Alternatively, bank financing can be utilised by local residents for construction with interest subvention from the under the PM Awas Yojana (PMAY). The Punjab Budget for FY20-21 had already provided Rs 293 crore for PMAY (urban for FY20-21.

This combined financing method to construct medium rise affordable rental housing for manual workers can be a source of funds for the local governments in these villages, a source of income for the current residents. Moreover, the industrial workers and their families will get access to basic social infrastructure required for human development. As it is, industrial workers live in these areas but in poor conditions while paying a non uniform rent to landowners.

Land areas with little or no agricultural activity can be targeted owing to lower cost of land acquisition. A high speed mass transit infrastructure can be established on on PPP/ DBFOT basis with long term concession period, to connect the residential area to the industrial zone and the rest of the city. This allows a phased development of the proposed industrial zones, wherein utilities and infrastructure reach the planned areas simultaneously.

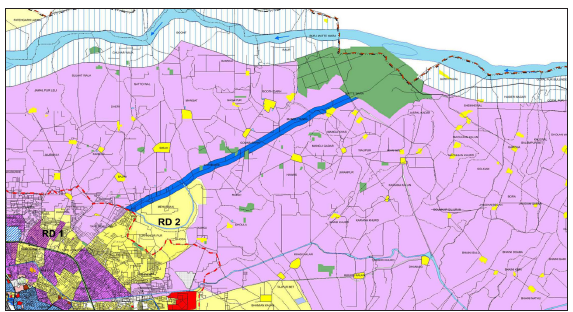

Example of Ludhiana: In Fig. 1 below, a portion of Ludhiana’s industrial zone in the master plan is depicted. The green belt visible in the image is the Mattewara forest. The Government of Punjab has already acquired 100 acres of land near the forest for proposed Cycle Valley project and payments to the tune of Rs 120 crore have been made to the concerned panchayats. The GoP is well on its way to acquire 1000 acres nearby for Ludhiana Industrial Park project, of which 47 acres have already been acquired from two villages. The payment of around Rs 8 crore has been made to the concerned panchayats. The land can be earmarked for affordable housing from within the land already acquired close the residential zones, or additional land can be acquired for this purpose.

Fig. 1 Industrial Zone (purple) in Ludhiana with residential/ villages (yellow) in the Ludhiana Master Plan 2031 (PUDA)

Agriculture in Punjab

Agriculture has been the mainstay of Punjab’s economy, and is most likely to be the way out of the pandemic induced economic slump in the medium term. Low investment in value chain, low capital formation, plateaued yields, highly depleted groundwater, and high chemical and low microbial content in the soil, high input costs and diminishing incomes are a few characteristics of agriculture in Punjab. What is required is a strategy to diversify cropping, limit exploitation of water, reduce usage of agrochemicals (highest in the country), and reorient the agriculture ecosystem towards wellness instead of survival. Wellness for both consumer as well as the producer.

The major challenge to diversification is assured procurement of rice and wheat. While wheat is suitable to the state’s agro-climatic conditions, paddy is not. The alternative to assured procurement is assured market. The southern districts of Bathinda, Mansa, Muktsar, Sangrur, Barnala, Faridkot, Moga and Firozpur, or almost the entire Malwa region has significant area under cultivation of cotton, a cash crop. Of these districts, in Bathinda and Mansa, paddy was at third rank in terms of value of production and cotton was at second in 2010-11. In Firozpur, Muktsat, Faridkot, Sangrur and Barnala, cotton was third. Cotton and paddy both consume high levels of pesticides, which is often correlated to high incidence of cancer in these districts. The area under horticulture in Bathinda, Mansa, Muktsar was at 0 ha (zero) and only 40 ha in Sangrur as per 2004 data. (All data from PUNENVIS). These districts present a low hanging opportunity to begin the diversification in Punjab and introduce cash crops, such as fruits, vegetables, and flowers. The assured market in in place from major urban agglomerations of Chandigarh tricity and Delhi NCR.

What is required at the onset is investment in on farm technology and equipment in terms of polyhouses, drip irrigation, underground pipes; farm gate infrastructure like cold storages, reefer vans etc.; and processing facilities in these districts. Shifting to horticulture could be supplemented with animal husbandry, as residue from horticulture is healthy organic feed for animals, and animal waste acts as a fertilizer on farm, further enriching the wellness agenda.

To facilitate this process of transformation, organising farmers into FPOs is very crucial. Apart from input expenditure rationalisation, FPOs bring much needed market linkages, discover best prices, reduce transaction costs and build long term sustainability of the ecosystem. These solutions can be piloted in Bathinda and Mansa as a first step, since the farmers there are not locked into the paddy-wheat crop cycle but have cotton cash crop experience.

Additional steps can be taken to reduce ground water exploitation all over the state. Since 2018, GoP has been implementing a scheme called “Paani Bachao Paisa Kamao (PBPK)” to incentivise farmers to use water and electricity more efficiently without retracting free power to agriculture policy. The scheme is an alternative model of DBTE to agriculture as electricity saved by the farmer (agriculture consumer) is monetised and cash transferred to the bank account of the consumer. This scheme is being implemented in phased manner and could be scaled up given enough data on effectiveness must be available with GoP form 6 feeders in 3 districts in phase 1 and 250 feeders in 11 districts in phase 2. 4

Footnotes:

1 Available on request from RGICS.

2 https://www.cseindia.org/punjab-faces-the-daunting-challenge-of-meeting-housing-requirements-of-the-urban-poor–8701

3 https://www.academia.edu/35684466/Magarpatta_City_Pune_India

4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qs15zsH7q2M&feature=youtu.be