Secularism, it has been argued, failed to stem the spread of communalism in ·India, because its marginalising and contempt of religion bred a backlash on which communalism thrived. This article contends that this ‘contempt for religion’ was marginalised in the course of the secularism debates in the Constituent Assembly. The dominant position on secularism that a ‘democratic’ Constitution find place for religion as a way of life for most Indians triumphed over those who wished for the Assembly to grant only a narrow right to religious freedom, or to make the uniform civil code a fundamental right. These early discussions on religious freedom also highlight a paradox – it is precisely some of the advocates of a broad right to religious freedom who were also the most vociferous opponents of any political rights for religious minorities.

The Preamble and Conceptions of Secularism

When 1he preamble to the Constitution was discussed in the Constituent Assembly on October 17, 1949, disagreement and acrimonious debate over the incorporation of the principle of secularism look up most of the Assembly’s time. The positions spelt out on secularism on that day show up clearly the lines of difference that had been developing on this issue during the three years of the Constituent Assembly debates.

On that day H V Kamath began the discussions by moving an amendment to begin the preamble by the phrase, ‘In the name of god’. Shibban Lal Saksena and Pandit Govind Malaviya also moved similar amendments later in the day. Responding to Pandit Kunzru’s objection that in invoking “the name of god, we are showing a narrow, sectarian spirit”, Pandit Malaviya argued that it was not anti-secular for the preamble to begin with expressions such as “By the grace of the Supreme Being, lord of the universe, called by different names by different peoples of the world”, since it was clear that not any particular religion’s god was being sanctified. Saksena pointed out that even the Irish constitution took god’s name at the beginning of its preamble.

Whereas the other two withdrew their proposals, Kamath stuck to his guns. Rajendra Prasad tried persuading him that his amendment was against the spirit of religious freedom of the Constitution that was exemplified, for instance, in the choice in the form of the oath – to ‘swear in the name of god’, or to ‘solemnly affirm’ – that the Constitution gave to ministers taking office. Kamath responded: ”Here we are not individuals. Here we are all the people of India. There is much difference between the two.” Religion was ‘the voice of our ancient civilization’ and the preamble, a document of the people of India, by taking god’s name only reflected the spirit and will of the Indian people.

Opponents to Kamath’s amendment continued to insist that religion was a matter of individual choice and in this matter the collective will should not be imposed. Another interesting objection was raised by Purnima Banerji who said that references to god should not be put into the constitution since that would make the sacred depend on the vagaries of democratic voting. She requested Kamath “not to put us to the embarrassment of having to vote upon god”.

Kamath’s amendment was defeated by 68 to 41, but neither did the Assembly accept a suggestion from the other side to include the word ‘secular’ in the preamble. Brajeshwar Prasad from Bihar moved that the first sentence of the preamble begins as follows: “We the people of India, having resolved to constitute India into a secular cooperative Commonwealth to establish socialist order and to secure to all its citizens… ” because he said that this word, ‘secular’ was dear to India’s national leaders and its inclusion in the preamble would tone up the morale of minorities as well as prevent disorderly activity. Unfortunately there was no discussion on the inclusion of the term ‘secular’; most members ridiculed Brajeshwar Prasad’s attempt at making the Constitution a socialist instead of a liberal democratic document and his amendment was negatived for that reason.

The preamble was discussed in one of the last-sessions of the Constituent Assembly which is why the theoretical positions on secularism that we try to extrapolate from the October 17 debate reflect the stands taken during the preceding three years. All the members agreed, of course, on the necessity of establishing a secular state. Most shared an understanding of history in which the “movement for the separation of religion and state was irrevocably a part of the project for the democratisation of the latter”. How could a democratic state represent a religious majority at the expense of the rights and liberties of a minority?

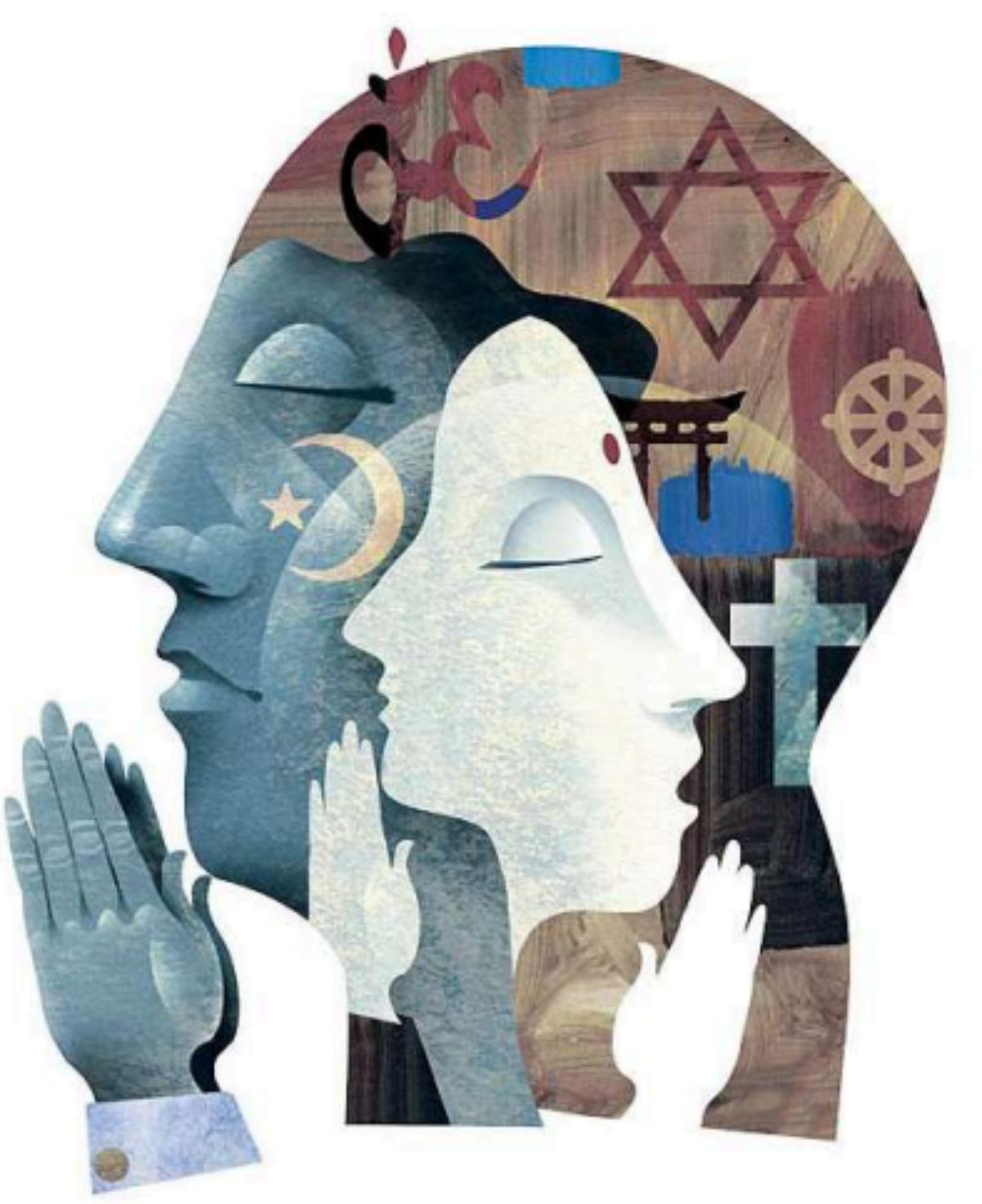

In Europe, “the idea of democratic dissent was posed initially as the idea of religious difference. It gradually became the premise for the liberties of the individual in general, and, in raising the question of equality and equal rights for all, the idea of secularism became the chief motor behind the subsequent idea of political democracy”. Since independent India was to be a democracy, secularism was a fait accompli: “it is essential for the proper functioning of democracy that communalism should be eliminated from Indian life”. But the question remained as to the kind of secularism to be established by Indians faced with the problem of “creating a secular state in a religious society”. Was a state secular only when it stayed strictly away from religion, and could such a secular state survive only if society was slowly secularised as well? Or did a state that equally respected all religions best capture the meaning of secularism in the Indian context?

On this issue we can see three alternative positions in the controversy around the preamble. The first – which we call the noconcern theory of secularism – saw a definite line of separation between religion and the state. Given the principles of freedom of expression and religious liberty, it was up to the individual to decide whether to be a believer or not, or to adhere to this religion or that. Therefore the preamble could not contain any references to god, and neither should the constitution establish links between the state and any religion. This argument of religion being an individual’s private affair, was extended during the main sessions of the Constituent Assembly to include the more radical claim that religion must be relegated to the private sphere. Many members declared that the need of the hour was to strengthen the identity of Indians as citizens of the Indian state, as opposed to being members of some community or religious group. Radhakrishnan’s speech on the Objectives Resolution on December 13, 1946 asserted that “nationalism, not religion, is the basis of modern life… the days of religious states are over. These are the days of nationalism”.

A month later, GB Pant. speaking to the Advisory Committee of the Constituent Assembly proclaimed that the ”individual citizen who is really the back bone of the state,…has been lost here in that indiscriminate body known as the community. We have even forgotten that the citizen exists as such. There is the unwholesome, and to some extent, degrading habit of thinking always in terms of communities and never in terms of citizens”. Similar thoughts were expressed later in an exaggerated fashion by Guptanath Singh: “The state is above all gods. It is the god of gods. I would say that a state being the representative of the people, is god himself’.

These positions logically led to a conception of a secular state as one that stays away from religion per se. It distances itself from all religions and in this manner encourages their limitation to a private sphere; it presses for the narrowing of religion to the activity of religious worship and it assiduously replaces respect for religion with building nationalist citizens. India was engaged in creating a modern nation state and in this enterprise, religion, an obscurantist and divisive force, had no place.

Members advocating this kind of secularism included KT Shah, who as late as December 1948, demanded the insertion of.an article separating the state from any religious activities. Tajamul Husain not only wanted to define the right to religion as a right to ‘practise religion privately’, but also insisted that religious instruction was to be given only at home by one’s parents and not in any educational institutions. He also wanted to include the following clause in the constitution: “No person shall have any visible sign, mark or name and no person shall wear any dress whereby his religion may be recognised”. This implied an understanding of secularism in which “religion is a private affair between man and his god. It has no concern with anyone else in the world”. It is this conception of secularism which led M Masani and K T Shah to state earlier that while they supported an individual’s right to religious freedom, they “dissented from the inclusion among fundamental rights of any provision guaranteeing institutions belonging to any” religious community”.

Many of these proponents of no concern secularism were making the argument familiar to all students of early modern political theory. A state wanting to strengthen itself must encourage the philosophy of abstract individualism so as to weaken all associations in society other than itself. It can then replace these associations by itself as the locus of the individual citizen’s identity. Secularism on this view meant the gradual weakening of the bonds of religion and their replacement with nationalism. II meant that the state must not recognise religion as a public institution. It was not just a question of religious liberty but of the establishment of the paramountcy of the state. Religion was to be relegated to as narrow a sphere as possible so that the state could emerge as a modern Leviathan.

The second position on secularism, exactly opposite to the first, was that no links between the state and religion should be permitted, not because this would weaken the state, but because it would demean religion: Religion, a system of absolute truth could not be made subject to the whims of changing majorities by allowing the democratic state to have a say in religious affairs.

Like the first, the third position – which we call the equal- respect theory of secularism – also began with the principle of religious liberty, but held that in a society like India where religion was such an important part of most people’s lives, this principle entailed not that the state stay away from all religions equally, but that it respect all religions alike. In this view, instead of distancing itself from all religions or tolerating them equivalently as sets of superstitions which could be indulged in as long as they remained a private affair, a secular state based its dealings with religion on an equal respect to all religions. One of the main proponents of this view. K M Munshi, proclaimed that the ‘”non-establishment clause (of the US Constitution) was inappropriate to Indian conditions and we had to evolve a characteristically Indian secularism”. Munshi said: “we are a people with deeply religious moorings. At the same time, we have a living tradition of religious tolerance – the result of the broad outlook of Hinduism that all religions lead to the same god…In view of this situation, our state could not possibly have a state religion, nor could a rigid line be drawn between the state and the church as in the US”.

Lakshmi Kant Maitra and H V Kamath claimed that the Indian state should not disavow India’s “lofty religions and spiritual concepts and ideals”. The west was in crisis because of the dominance of materialism, and it was looking towards India for a regeneration of “spiritual values”. The Indian state should not encourage sectarianism, but at the same time it should actively “impart spiritual training or instruction to its citizens” by giving some kind of spiritual education to them.

It is this conception of secularism which led certain members to define the right to religion as a right to the practise of religion as opposed to the more narrow right to religious worship. These members accepted that certain limitations must be placed on this right. However, it was all right to have these limitations once the right had been framed properly to capture the significance of religion, instead of being framed in a manner which revealed a disregard for religion.

Since religion was for most Indians, a way of life and therefore essential to their identity, how could a people’s state be founded on a kind of secularism contemptuous of religion. One’s identity was not something which was easily changeable, and for these members to forcibly replace religion as the basis of one’s identity with the state was an attack on the autonomy of individuals.

In addition, most important religions contained principles of toleration within themselves since by definition, religious belief had to be voluntary. If the state allowed a public sphere to religion this would not automatically lead to inter-sectarian strife, as all great religions of the world preached forbearance of other faiths. J B Kripalani defined toleration as the acceptance, to some extent, of someone’s beliefs as good for him and argued that it was because the no-concern theory was based on a doctrine of intolerance that it confined religion to the private realm.

On the other hand a state which respected all religions was educating its citizens in principles of toleration: “We have to respect each other’s faith. We have to respect it as having an element of truth”. Jaya Prakash Narayan added that it was only when religion was used to serve socio economic and political interests, that there was communal violence. What needed to be done in the interests of secularism was to incorporate an article in the Constitution prohibiting the use of religious institutions for political purposes or the setting up of political organisations on a religious basis. It was not religion per se but its politicisation which engendered violence in the modern state.

The no-concern and equal-respect positions on secularism clashed constantly during the debates in the Constituent Assembly as the question of secularism cropped up in discussions around innumerable articles. The issue of secularism was ubiquitous – it came up even when parliamentary procedure and the linguistic reorganisation of states were being discussed. Instead of detailing the arguments on secularism around some randomly picked articles, we have, following Smith’s model that a secular Constitution must have provisions dealing with three specific subjects – religious liberty, citizenship and state neutrality – picked up the debate on some articles from each area to show the lines of disagreement amongst Constituent Assembly members.

Under religious liberty, we look at the controversy over whether the right to religious freedom should be the right to religious worship or to religious practice, and over whether the state should recognise only linguistic minorities or religious minorities as well. Under citizenship, we review the dispute over the uniform civil code and over political reservation for religious minorities; and finally for state neutrality we consider the debate over whether there should be religious instruction in state aided schools. Looking at the discussions in more detail, we find that it is the ambivalences within the no-concern and equal-respect camps that are more interesting than the stark contrast between the two positions.

Religious Practice or Religious Worship

On April 16, 1947 the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Rights of the Constituent Assembly determined the right to the freedom of religion to be a right “to freedom of conscience, to freedom of religious worship and to freedom to profess religion”. Two days later, the Constituent Assembly’s Minorities Sub-Committee decided by a majority of 10 to five that the freedom to religion should be rephrased as the “freedom of conscience and the right freely to profess, practice and propagate religion”. This change in terminology was formally dissented to by Amrit Kaur, Jagjivan Ram, G B Pant, P K Salve and- B R Ambedkar.

Sharp disagreement on whether to call the right to religion a right to religious practice or a right to religious worship had already become manifest in the proceedings of the Fundamental Rights Sub committee. This Committee’s draft report of April 3, reflecting the discussion on KM Munshi’s and Ambedkar’s proposed articles on fundamental rights, set out eight articles defining the right to religion. Article 16 followed Munshi’s proposal, instead of Ambedkar’s.

In giving the right “freely to profess and practice” religion, and in adding the explanation that the right “to profess and practice religion shall not include any economic, financial, political or other secular activities that may be associated with religious worship.” Anibedkar’s suggestions were incorporated in another explanation to Article 16 that “No person shall refuse the performance of civil obligation or duties on the ground that his religion so requires,” and in Article 19 that ”The state shall not recognise any religion as the state religion”.

That there were irreconcilable differences in the Constituent Assembly on religious freedom, and that the dispute over religious practice or religious worship was not a trifling disagreement over words was apparent in the inconsistency within Article 16 itself. Members supporting the use of the terms ‘the practice of religion’ said that to understand religion narrowly as a set of performative rituals in a ‘public but circumscribed place of worship like a church’ was to misunderstand the significance of religion for a believer. If religion was rightly understood as a way of life then Article 16 could not include the proviso that one’s civil obligations overrode one’s religious duties.

KM Panikkar used the example of ‘Sanyasa’, a fundamental element of religion in many sects, which rules that one’s life must be lived in a certain way: “Where religion provides that a Sanyasi shall have no attachments to the world, to ask that he shall perform civil duties is in fact to ask him to give up his religion.” Many things were part of religion, the least of them being the wearing of kirpans by Sikhs. Since the Constitution could not specify all the essential elements of the different Indian religions, at least it could phrase the right to religion broadly as the right to the practice of religion and not narrowly as the right to religious, worship. If the Constituent Assembly was serious about religious freedom then there was no point in granting a freedom to a religion denuded of all content.

Those on the other side of the divide pointed to the dangers of interpreting religion widely. Any such broad reading of religion would include within it the antisocial customs of” pardah, child marriage, polygamy, unequal laws of inheritance, prevention of intercaste marriage, (and) dedication of girls to temples,” practised in the name of religion. Rajkumari Amrit Kaur further pointed out that if the right to religion was stated in terms of the right lo the practice of religion, it “may even contradict or conflict with the provision abolishing the practice of untouchability” alternatively. If the right given were the right to religious worship. The state could better protect all the rights of individuals by preventing through social legislation the exploitation of a lower caste man by an upper caste individual, or of a woman by a man.

This dispute over the terminology of the right to religion led to much flip-flopping in the various reports of the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee. The April 3 draft used the terms ‘practice religion’; but because of reservations expressed by some members, the April 16 report of the Sub Committee changed the terminology to freedom of religious worship’. However on April 18, the Minorities Sub-Committee suggested that the original phraseology of the April 3 draft be used. After that the Advisory Committee of the Constituent Assembly, which included both the SubCommittees on Fundamental Rights and Minorities as well as three others, met and submitted an Interim Report on April 23 in which the right to religion was a right to “practice religion” and the proviso barring individuals from using religious reasons to exempt themselves from civic duties, as well as the article banning a state religion, were dropped.

It seemed as if one side had won an overwhelming victory, even though the right to the practice of religion remained limited by public order, morality, health and the other provisions of the chapter on fundamental rights, as well as by two provisos that the right to religion shall not include any economic, financial, political or other secular activities that may be associated with religious practice, and that it shall not debar the state from enacting laws for the purpose of social welfare and reform.

The battle was joined once again when the Interim Report of the Advisory Committee was presented to the Constituent Assembly on May 1, 1947. This time doubts were raised about including the right to propagate in religious freedom; some members wanted it clarified that the conversion of minors would not be al lowed. Those who protested that this would mean that parents who had converted had no right to determine the religious upbringing of their children, had their way, and in the draft Constitution of February 1948, the article postulating restrictions on the act of religious conversion was dropped.

When the draft Constitution’s articles on religion were discussed in the Constituent Assembly in December 1948, K T Shah raised the demand again that an article be included expressly forbidding any link between the state and religion. Such an article would begin as: “The state in India being secular shall have no concern with any religion, creed or profession of faith”. Tajamul Hussain wanted to replace the terms ‘practice and propagate religion’ with ‘practice religion privately’. We see then that the exact phrasing of the main article on religious freedom remained contentious till the very last.

Linguistic or Religious Minorities

The differences over secularism were also clearly apparent in the controversy over whether a secular state permits the recognition of religious minorities along with linguistic minorities. On the one hand, Jaya Prakash Narayan held that the “secularisation of general education… necessary for the growth of a national outlook and unity” required that the cultural and educational rights guaranteed in the Constitution should be confined only to linguistic minorities. On the same lines, Damodar Swarup Seth suggested that “the only minorities to be recognised should be those based on language: recognition of minorities based on religion or community was not in keeping with the secular character of the state. If such minorities were granted the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their own, it would not only block the way to national unity but would also promote communal ism and an anti-national outlook.” It was with similar reservations in· mind that G B Pant had earlier, in an April 1947 meeting of the Minorities Sub-Committee, suggested that the cultural and educational rights of minorities be included among the non-justiciable directive principles. Rajkumari Amrit Kaur had similarly proposed that religious minorities not be allowed to set up separate educational institutions, nor state aid be provided to these institutions.

As these articles were framed in the Minorities Sub-Committee, however, they reflected the point or view of the other side. The draft rights defined minorities in terms of religion and language and gave them the right to establish and administer educational institutions. The Constituent Assembly also passed these articles in the same form: “all minorities, whether based on religion or language had the right to establish and administer educational institutions” (Article 30, Constitution of India) which were entitled to state aid just as any other educational bodies.

Uniform Civil Code

The first article that we take up with reference to citizenship in a secular state is that on the uniform civil code. Both Munshi’s and Ambedkar’ s draft articles of March 1947 on justiciable rights contained clauses referring indirectly to a uniform civil code, Munshi’s proposal stated that: ”No civil or criminal court shall, in adjudicating any matter or executing any order recognise any custom or usage imposing any civil disability on any person on the ground of his caste, status, religion, race or language”. Ambedkar wrote that the subjects of the Indian state shall have the right “to claim full and equal benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and property as is enjoyed by other subjects regardless of any usage or custom based on religion and be subject to like punishment, pains and penalties and to none other”.

By March 30, however, the Fundamental Rights Sub-Committee had decided to make the uniform civil code a directive principle of state policy. In her letter of March 31, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur emphasised the importance of the uniform civil code and called it “very vital to social progress”. In a much more strongly worded note of April 14, Amrit Kaur, along with Hansa Mehta and MR Masani, wrote that.”(o)ne of the factors that has kept India back from advancing to nation hood has been the existence of personal laws based on religion which keep the nation divided into watertight compartments in many aspects of life”, and demanded that the provision regarding the uniform civil code be transferred from the chapter on directive principles to that on fundamental rights.

This position was opposed by other members of the Constituent Assembly, such as Mohamed IsmaiI Saheb, supported by B Pocker Sahib, who wanted to include a right to one’s personal law in the fundamental right to religion. Failing that, they insisted that at least the directive principle enjoining the state to provide a uniform civil code, should contain the following proviso: “Provided any group, section or community of people shall not be obliged to give up its own personal law in case it has such a law”. This must be done if the right to religious practice was to have any reality because the “right to follow personal law is part of the way of life of those people who are following such laws; it is part of their religion and part of their culture”.

Mahboob Ali Baig Bahadur said, “People seem to think that under secular state, there must be a common law observed by its citizens in all matters including matters of their daily life, their language, their culture, their personal laws. This is not the correct way to look at the secular state. In a secular state, citizens belonging to different communities must have the freedom to practise their own religion, observe their own life and their personal laws should be applied to them”. These members were opposed to the setting up of a uniform civil code.

An intermediate position was that the establishment of the uniform civil code must be done slowly, with the consent of all communities. Similar to this position was that of K M Munshi’s – who now, surprisingly, wanted to narrow the definition of religious practice. He pointed out that the personal law of Hindus was discriminatory ‘against women and contravened an Indian citizen’s right to equality. Therefore, “religion must be restricted to spheres which legitimately appertain to religion, and the rest of life must be regulated, unified and modified in such a manner that we may evolve, as early as possible, a strong and consolidated nation.” Ambedkar can also be put in this group since he supported the inclusion of the uniform civil code in the directive principles but said that the code would only apply to those who wanted it to apply to them.

Political Safeguards for Minorities

Simultaneously with discussing the kind of religious rights permitted by secularism, the Constituent Assembly’s members also debated the political rights of minorities in a secular state. The Minorities SubCommittee based ‘itself on its members’ responses to a short questionnaire on safeguards for minorities prepared by KM Munshi, and on Ambedkar’s suggested safeguards for the scheduled castes. Munshi’s questionnaire consisted of six queries on the nature and scope of political, economic, religious, educational and cultural safeguards for a minority at the centre and the provinces in the new constitution, on the machinery to ensure these safeguards, and on whether these safeguards would be temporary or permanent. Ambedkar’s draft contained a section on ‘provisions for the protection of minorities’ demanding that the· representatives of the different minorities in the cabinet be elected by members of each minority community in the legislature, as well as the establishment of a superintendent of minority affairs. Although only the scheduled castes were specifically named as a minority by Ambedkar, he did assume the inclusion of other minorities when he wrote that the share of the scheduled castes in the reserved seats in the legislatures or the services would not be at the cost of the share of the other minorities.

In his draft provisions, Ambedkar stated that social discrimination constituted the real test for determining whether a social group is or is not a minority. thus both the scheduled castes and certain religious groups were minorities in India. “since the administration in India is completely in the hands of the Hindus, and under Swaraj the legislature and executive will also be in the hands of the Hindus”. According to Ambedkar, Indian nationalism had developed a doctrine called “the divine right of the majority to rule the minorities according to the wishes of the majority. Any claim for the sharing of power by the minority is called communalism while the monopolising of the whole power by the majority is called nationalism”.

In this context it was essential for equal citizenship that political safeguards for minorities be enshrined in the Constitution. The Minorities Sub-Committee following Ambedkar’s draft articles began with proposals to establish, for religious minorities and for scheduled castes and tribes, separate electorates, and reservation in legislative bodies, ministries, and the civil, military and judicial services of the government as well as a Minorities Commission. When discussions took place in the Sub-Committee in July 1947, by which time the question of partition had been decided, and the Muslim League members had also joined the Constituent Assembly, the demand for separate electorates and for reservation in the ministries and the government services was given up.

On August 8. the Advisory Committee submitted its report on minorities stating that separate electorates were to be abolished because they “sharpened communal differences to a dangerous extent and have proved one of the main stumbling blocks to the development of a healthy national life”. So that the minorities did not feel threatened, the Muslims and scheduled castes were granted reservation in the legislatures, in proportion to their population, for 10 years. There was also some kind of reservation for Anglo- Indians and the question was left open for Parsees, Sikhs and tribals. There was also to be a special minority officer at the centre and each of the provinces.

When this report was considered in the Constituent Assembly on August 27, 1947, many of the members against separate electorates blamed British institutional arrangements for the communal discord in India: for instance, P S Deshmukh said that “the demon of the interests of minorities and their protection was a creation of British policy”. Members still supporting the provision of separate electorates argued that without them, the best representative of a minority community would not be elected. However separate electorates were not reinserted into the Constitution. Nor was an amendment moved by S Nagappa and supported by Arnbedkar, that a scheduled caste candidate could only be declared elected to a scheduled caste reserved seat on securing at least 35 percent of votes polled by scheduled castes to that seat, passed.

In the February 1948 Draft Constitution, Articles 292 and 294 reserved seats in parliament and state legislatures for Muslims, scheduled castes, Scheduled Tribes and Indian Christians for 10 years. In February 1948, a special subcommittee of Patel, Nehru, Prasad, Munshi and Ambedkar was formed on minority problems affecting East Punjab and West Bengal. This Committee rejected the demand of the Shiromani Akali Dal for a separate electorate on the grounds that although “it is not always easy to define communalism, there could be little doubt that separate electorates are both a cause and an aggravated manifestation of this spirit”. The committee’s report was quite critical of the demands of the Akali Dal and rejected every one of them since they ”disrupted the whole conception of the secular state which is to be the basis of our new Constitution”.

When this report was considered in the Advisory Committee in December 1948, a suggestion was made that reservations in legislative bodies should also be given up. By May 11, 1949, Muslims and Indian Christians lost their reserved seats. The understanding was that the non-Muslim League Muslims were under instructions of Maulana Azad not to press for reservation. Nehru responded to a speech by Begum Rasul against reservation by saying. “I think that doing away with this reservation business is not only a good thing in itself, good for all concerned, more especially for the minorities, but psychologically too it is a very good move for the nation and the world. It shows that we are really sincere about this business of having a secular democracy”.

In his report on this May 11 meeting, Patel wrote: “Although the abolition of separate electorates had removed much of the poison from the body politic, the reservation of seats for religious communities, it was felt, did lead to a certain degree of separatism and was to that extent contrary to the conception of a secular democratic state”. In moving this report in the Constituent Assembly on May 25, 1949, he exhorted everyone “to forget that there is anything like majority or minority in this country and that in India there is only one community”.

Religious Instruction in Educational Institutions

For our next subject of state neutrality, we go back to the right to religion, and examine what happened to the issue of religious instruction. The Advisory Committee in its interim report of April 23, I947 had stated that religious instruction must be voluntarily received in schools maintained or getting aid out of public funds. When this clause was discussed in the Constituent Assembly on August 30, 1947, it was sought to be amended by Renuka Ray to read as follows: “No denominational religious instruction shall be provided in schools maintained by the state”.

Radhakrishnan explained the reasoning behind such an amendment: “We are a multi-religious state and therefore we have to be impartial and give uniform treatment to the different religions: but if institutions maintained by the state, that is, administered, controlled and financed by the state are permitted to impart religious instruction of a denominational kind, we are violating the first principle of our Constitution.” Here we see at its clearest, one understanding of secularism: impartiality to all religions means that the state must stay away from all religions. When this article was discussed again in the Constituent Assembly in December 1948, KT Shah went further and demanded that religious instruction should be banned not only in educational institutions wholly maintained out of state funds, but also in those which were aided or partIy maintained by the state. He said that he did not want education to become a menagerie of faiths. Tajamul Husain said the religious instruction should only be given at home by one’s parents.

Diametrically opposite was the argument of Mohamed Ismail who believed that “the stability of society as well as of the state could be secured through a moral background which religion alone could provide, and it was in the interest of the state itself to give children a grounding in religion”. Thus there ought to be no bar on religious instruction in educational institutions, not even in those run exclusively by the state, as long as no one was compelled to accept such instruction. If religious instruction was imparted in this manner by the state. It would in no way contravene the neutrality or the secular nature of the state.

H V Kamath also supported the imparting of spiritual instruction to the citizens by the state. The “deeper import of religion the eternal values of the spirit…could be imparted by the state without violating the principle of secularism”. Further he pointed to the contradiction between this article on religious instruction and the subsequent one on the cultural and educational rights of minorities. If on the one hand, the Constitution stated that minorities were entitled to state aid and recognition to their freely run educational institutions, then how could it also ban religious instruction in state aided institutions. The only solution was to say that no pupil could be forced to attend religious instruction in state aided schools.

Conclusion

Ever since the Romantics, we have learnt that contradictions are not a problem; they capture better the complexity of anything. But surely a Constitution – a legal document – has to obey canons of consistency? Both the no-concern and equal-respect positions on secularism, when constructed strictly logically by Rajkumari Amrit Kaur and B Packer Sahib, had few takers in the Constituent Assembly. Most members felt that neither a position demanding a right only to religious worship, the recognition by the state of no minority, whether religious, linguistic or sexual, the establishment of a uniform civil code, no political safeguards for any minority and no religious instruction in any state schools, nor its mirror opposite, claiming a right to the practice of religion, state recognition for religious as well as linguistic minorities, personal laws to be included in fundamental rights, political safeguards for all religious minorities, and religious instruction in state schools, captured the requirements of secularism in the context of India’s social diversity.

The first position suffered from a ‘statist’ conception of nationalism, “giving an inescapably statist’ orientation to the very conception of any political unity across religious communities and other social divisions”. It wished to establish a direct link between the citizens and the state, by weakening all other loyalties and commitments of individuals. Apart from neglecting the importance of cultural and religious considerations to one’s identity, this conception of secularism reflected a naive belief in the benign nature of the modern democratic state. The second position was weakened by its failure to provide any avenues for dissent within different religious communities.

Much more important were two intermediate positions in the Constituent Assembly, one of which sought, for instance, to combine the right to religious worship and to a uniform civil code with political reservation for minorities. This position lost, and the one which is reflected in the actual articles of the Constitution, defined the right to religion broadly as the right to religious practice, but refused to grant political safeguards to religious minorities.

Today, we are inclined to favour a conception of a secular state as an equal respecter of all religions. Can the Constituent Assembly debates throw any light on whether this conception requires not only, that religion be defined broadly by the state, but also that minorities must be granted political safeguards. Is this the only way that the state can prevent itself from becoming a Hindu state or will this added provision worsen the situation for Indian democracy?

Supreme Court Judgment dated Nov 25, 2024 on the word Secularism in the Preamble

Writ Petition (C) No 645 Of 2020 and Writ Petition (C) No 1467 Of 2020, Dr Balram Singh and Others, Petitioners Versus Union of India and Another. Respondents sought to challenge the insertion of the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ in the Preamble to the Constitution of India by the Constitution (Forty-second Amendment) Act in 1976. The challenge is on various grounds, namely, retrospectivity of the insertion in 1976, resulting in falsity as the Constitution was adopted on the 26th day of November 1949; the word ‘secular’ was deliberately eschewed by the Constituent Assembly, and the word ‘socialist’ fetters and restricts the economic policy choice vesting in the elected government, which represents the will of the people. Besides, it is submitted that the Forty-second Amendment vitiated and unconstitutional as it was ‘passed’ during the Emergency on November 2, 1976, after the normal tenure of the Lok Sabha that had ended on March 18, 1976. Therefore, it is argued, that there was no will of the people to sanction the amendments.

The writ petitions do not require detailed adjudication as the flaws and weaknesses in the arguments are obvious and manifest. Two expressions—’secular’ and ‘socialist’ and the word ‘integrity’ were inserted in the Preamble vide the Constitution (Forty-second Amendment) Act, 1976. These amendments were made in 1976. Article 368 of the Constitution permits amendment of the Constitution. The power to amend unquestionably rests with the Parliament. This amending power extends to the Preamble. Amendments to the Constitution can be challenged on various grounds, including violation of the basic structure of the Constitution. The fact that the Constitution was adopted, enacted, and given to themselves by the people of India on the 26th day of November, 1949, does not make any difference. The date of adoption will not curtail or restrict the power under Article 368 of the Constitution. The retrospectivity argument, if accepted, would equally apply to amendments made to any part of the Constitution, though the power of the Parliament to do so under Article 368, is incontrovertible and is not challenged.

While it is true that the Constituent Assembly had not agreed to include the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ in the Preamble, the Constitution is a living document, as noticed above with power given to the Parliament to amend it in terms of and in accord with Article 368. In 1949, the term ‘secular’ was considered imprecise, as some scholars and jurists had interpreted it as being opposed to religion. Over time, India has developed its own interpretation of secularism, wherein the State neither supports any religion nor penalizes the profession and practice of any faith. This principle is enshrined in Articles 14, 15, and 16 of the Constitution, which prohibit discrimination against citizens on religious grounds while guaranteeing equal protection of laws and equal opportunity in public employment.

The Preamble’s original tenets—equality of status and opportunity; fraternity, ensuring individual dignity—read alongside justice – social, economic political, and liberty; of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship, reflect this secular ethos. Article 25 guarantees all persons equal freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion, subject to public order, morality, health, other fundamental rights, and the State’s power to regulate secular activities associated with religious practices. Article 26 extends to every religious denomination the right to establish and maintain religious and charitable institutions, manage religious affairs, own and acquire property, and administer such property in accordance with law. Furthermore, Article 29 safeguards the distinct culture of every section of citizens, while Article 30 grants religious and linguistic minorities the right to establish and administer their own educational institutions. Despite these provisions, Article 44 in the Directive Principles of State Policy permits the State to strive for a uniform civil code for its citizens.

A number of decisions of this Court, including the Constitution Bench judgments in Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala[2] and S R Bommai vs Union of India[3], have observed that secularism is a basic feature of the Constitution. In R C Poudyal v. Union of India[4], the Court elucidated that although the term ‘secular’ was not present in the Constitution before its insertion in the Preamble by the Constitution (Forty-second Amendment) Act, 1976, secularism essentially represents the nation’s commitment to treat persons of all faiths equally and without discrimination. In M Ismail Faruqui (Dr) v. Union of India[5], this Court elaborated that the expression secularism in the Indian context is a term of the widest possible scope. The State maintains no religion of its own, all persons are equally entitled to freedom of conscience along with the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate their chosen religion, and all citizens, regardless of their religious beliefs, enjoy equal freedoms and rights. However, the ‘secular’ nature of the State does not prevent the elimination of attitudes and practices derived from or connected with religion, when they, in the larger public interest impede development and the right to equality. In essence, the concept of secularism represents one of the facets of the right to equality, intricately woven into the basic fabric that depicts the constitutional scheme’s pattern.

Similarly, the word ‘socialism’, in the Indian context should not be interpreted as restricting the economic policies of an elected government of the people’s choice at a given time. Neither the Constitution nor the Preamble mandates a specific economic policy or structure, whether left or right. Rather, ‘socialist’ denotes the State’s commitment to be a welfare State and its commitment to ensuring equality of opportunity. India has consistently embraced a mixed economy model, where the private sector has flourished, expanded, and grown over the years, contributing significantly to the upliftment of marginalized and underprivileged sections in different ways. In the Indian framework, socialism embodies the principle of economic and social justice, wherein the State ensures that no citizen is disadvantaged due to economic or social circumstances. The word ‘socialism’ reflects the goal of economic and social upliftment and does not restrict private entrepreneurship and the right to business and trade, a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(g).

The argument that the Constitution (Forty-second Amendment) Act, 1976, should be struck down due to its enactment during the Emergency and the extended period of the Lok Sabha was previously deliberated in Parliament, during the consideration of the Constitution Forty-Fifth Amendment Bill, 1978. During these deliberations, the inclusion of the words ‘secular’ and ‘socialist’ came under scrutiny. Subsequently, this Bill was renumbered and called the Constitution Forty-Fourth Amendment Act 1978. The word ‘secular’ was explained as denoting a republic that upholds equal respect for all religions, while ‘socialist’ was characterized as representing a republic dedicated to eliminating all forms of exploitation—whether social, political, or economic. However, the said amendment as proposed to Article 366 was not accepted by the Council of States.

No doubt, in Excel Wear v. Union of India and Others[6] this Court had held that the addition of the word socialist in the Preamble may enable the Court to lean more in favour of nationalization and State ownership of industries, yet this Court recognized private ownership of industries, which forms a large portion of the economic structure. The majority judgment of this Court in the 9-Judge Constitution Bench in Property Owners Association and Others v. State of Maharashtra and Others [7] has cleared any doubt and ambiguity, as it is held that the Constitution, as framed in broad terms, allows the elected government to adopt a structure for economic governance which would sub-serve the policies for which it is accountable to the electorate. Indian economy has transitioned from the dominance of public investment to the co-existence of public and private investment.

The fact that the writ petitions were filed in 2020, forty-four years after the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ became integral to the Preamble, makes the prayers particularly questionable. This stems from the fact that these terms have achieved widespread acceptance, with their meanings understood by “We, the people of India” without any semblance of doubt. The additions to the Preamble have not restricted or impeded legislations or policies pursued by elected governments, provided such actions did not infringe upon fundamental and constitutional rights or the basic structure of the Constitution. Therefore, we do not find any legitimate cause or justification for challenging this constitutional amendment after nearly 44 years. The circumstances do not warrant this Court’s exercise of discretion to undertake an exhaustive examination, as the constitutional position remains unambiguous, negating the need for a detailed academic pronouncement. This being the clear position, we do not find any justification or need to issue notice in the present writ petitions, and the same are accordingly dismissed.

Pending applications, including the applications for intervention, shall also stand dismissed.

Miscellaneous Application No 835 of 2024

- The Miscellaneous Application is allowed. The Registry is directed to register the Writ Petition (Civil) Diary No. 14904 of 2024.

- In view of the order passed in Writ Petition (Civil) 645 of 2020 and Writ Petition (Civil) No.1467 of 2020, the Writ Petition shall be treated as dismissed..

[Sanjiv Khanna CJI., Sanjay Kumar, J.]

New Delhi; November 25, 2024.

[1] Economic and Political Weekly, Vol 37, Issue 30, 27 July 2002 https://www.epw.in/journal/2002/30/special-articles/secularism-constituent-assembly-debates-1946-1950.html Reproduced with gratitude.

[2] (1973) 4 SCC 225 (13 Judges)

[3] (1994) 3 SCC 1 (9 Judges)

[4] (1994) Supp (1) SCC 324

[5] (1994) 6 SCC 360

[6] (1978) 4 SCC 224

[7] 2024 INSC 835