The Current Situation

Human trafficking is considered among the most “profitable” transnational crimes of the 21st century. Growing at an unprecedented rate, it is next only to arms deals and drugs trafficking. Human trafficking is considered the third largest organized crime in the world today. Both within a country and across borders, there is no doubt that it is a social malaise, a crime against humanity itself.

Every year, scores of vulnerable individuals, especially women and children, fall prey to the extremely well-organised trafficking syndicates, who lure them into deplorable situations from where there is often no escape. Women and girls make up to 55% of those forced or coerced into some form of modern slavery (commercial sexual exploitation or forced labour), as compared to 45% men and boys. The common notion that victims end up being trafficked through coercion or force is misleading. Victims are typically recruited with false promises for a better life through fake incentives of lucrative employment opportunities, free education, marriage and even careers in huge entertainment and hospitality sectors in India and abroad.

The Situation in India: Its Magnitude

As reported over the past five years by the UNHCR, India is a source, destination, and transit country for men, women, and children subjected to forced labour and sex trafficking. It is noted that around 90% of human trafficking is inter-state i.e. within the country with only 10% of the victims being sent across borders. More chilling is the fact that every eighth minute, a child goes missing (read.trafficked) in India, according to government sources.

Trafficked children are subjected to forced labour as factory and agricultural workers, carpet weavers, domestic servants, and beggars. Children continue to be subjected to sex trafficking in

| CATEGORY WISE DETAILS AS ON 12-09-19 : | |||

|

Category |

No. of Children during the Time Period | ||

| Last 24 Hours | Last 30 Days | Last One Year | |

| Missing | 26 | 547 | 5600 |

| Recovered (Police) | 13 | 335 | 3020 |

(Source: Khoya-Paya data on missing children as of 12.09.2019)

religious pilgrimage centers and by foreign travelers in tourist destinations. Forced labour constitutes India’s largest trafficking problem; men, women, and children in debt bondage – sometimes inherited from previous generations – are forced to work in brick kilns, rice mills, embroidery factories, and agriculture. As aforementioned, most of India’s trafficking problem is internal, and those from the most disadvantaged social strata – lowest caste Dalits, members of tribal communities, religious minorities, and women and girls from excluded groups are most vulnerable. They are subjected to forced, often, bonded labour in sectors such as construction, steel, garment, and textile industries, wire manufacturing for underground cables, biscuit factories, pickling, floriculture, fish farms, and ship breaking. Thousands of unregulated work placement agencies reportedly lure adults and children under false promises of employment into sex trafficking or forced labour, including domestic enslavement.

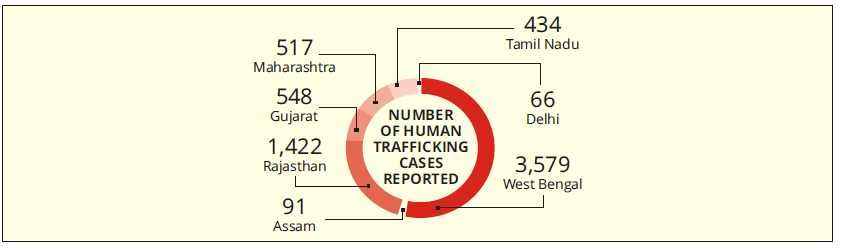

Experts estimate millions of women and children are victims of sex trafficking in India. The NCRB reported the government’s identification of 22,955 victims in 2016, compared with 8,281 in 2015. The report further stated that 11,212 of the victims of both genders were exploited in forced labour, 7,570 exploited in sex trafficking, 3,824 exploited in an unspecified manner, and 349 exploited in forced marriage, although it is unclear if the forced marriage cases directly resulted in forced labor or sex trafficking. The statistics of the Ministry of Women and Child Development states that 19,223 women and children were trafficked in 2016 against 15,448 in 2015, with the highest number of victims being recorded in the eastern state of West Bengal.

(Source: DNAIndia.com reflecting NCRB data, 2016)

Many women and girls, predominately from Nepal and Bangladesh, and from Europe, Central Asia, Africa, and Asia, including Rohingya and other minority populations from Burma, are subjected to sex trafficking in India. Prime destinations for both Indian and foreign female trafficking victims include Kolkata, Mumbai, Delhi, Gujarat, Hyderabad, and along the India- Nepal border. Following the 2015 Nepal earthquakes, Nepali women who transit through India are increasingly subjected to trafficking in the Middle East and Africa. Traffickers use false promises of employment or arrange sham marriages within India or Gulf states and subject women and girls to sex trafficking. In addition to traditional red light districts, women and children increasingly endure sex trafficking in small hotels, vehicles, huts, and private residences. Traffickers increasingly use websites, mobile applications, and online money transfers to facilitate commercial sex. It is disturbing to find some corrupt law enforcement officers protecting suspected traffickers and brothel owners from law enforcement efforts, take bribes from sex trafficking establishments and sexual services from victims, and tip off sex and labour traffickers to impede rescue efforts.

International Legal Framework and Legal Provisions in India

The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHR), the UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the UN Special Rapporteur on Violence Against Women and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) have all adopted definitions of trafficking that recognize it as a human rights problem involving forced labor, servitude or slavery and not a problem limited to prostitution.1 The United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (often also called the Palermo Protocol), adopted by General Assembly resolution 55/25 of 15 November 2000, is the main international instrument in the fight against transnational organized crime2. The Convention is further supplemented by three protocols, which target specific areas and manifestations of organized crime, one of which is the protocol to prevent, suppress and punish those involved in trafficking of Persons, especially of women and children.

India has ratified two very important international instruments of optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, in August 2005. In May 2011, Government of India ratified the United Nations Convention against Trans-national Organized Crime (UNTOC) and its three protocols. Although commercial sexual exploitation remains the most widely recognised outcome and form of human trafficking, other forms of trafficking have found their way into public discourse as well as in implementation strategies. This significant shift in recognition of multiple forms and purposes of trafficking has been the result of committed campaign and advocacy by the civil society in India.

That this recognition is reflected in the country’s legal provisions as well is heartening to note. It was following the ratification of the Palermo Protocol which resulted in India further expanding its definition of trafficking. The new definition was included in the Indian legal framework as Section 370 of the Indian Penal Code, following the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013, famously known as the Nirbhaya Act.

Post this, there have been other encouraging changes in the legal and policy framework. The mandate to establishment of Anti-Human Trafficking Units (AHTUs) to address the issue has been the most noteworthy. Several Advisories and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) have also been drafted by different ministries, especially by the Ministry of Home Affairs, following Supreme Court orders.

The government of India, through legislation and policy making, has clearly stepped up its efforts to battle human trafficking. In February 2018, the Union Cabinet, chaired by the Prime Minister, approved the Trafficking in Persons (Prevention, Protection and Rehabilitation) Bill for introduction in the Parliament. If passed, the Bill would address the issue of trafficking from the “point of view of prevention, rescue and rehabilitation,” criminalize aggravated forms of trafficking, and create a national anti-trafficking bureau to comply with a December 2015 Supreme Court directive to establish an anti-trafficking investigative agency. The creation of such an agency was pending the passage of the Anti-trafficking Bill, although the Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) had allocated 832 million Indian rupees (INR) ($13.1million) to the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) for the agency.

Gaps in Translating Policy to Practice

This multilayered crime can challenge both policy makers and practitioners. Human trafficking cannot be tackled in isolation as it is rooted in deeper issues that are social and economic in nature and extremely difficult to grasp and even harder to track given how organized yet pernicious the crime is. Importantly, how governments address human trafficking depends largely on the way authorities perceive the crime. When officials view trafficking as a crime and have a precise understanding of its core elements, they are better equipped to identify and combat it, regardless of any scheme the trafficker uses. Over the years, though the commitment of the Government of India is improving as reflected in policy provisions, and the civil society is equally demonstrating steadfast action to tackle trafficking; however, the gaps that make this challenging remain.

Inadequate Coordination between Stakeholders

There are several initiatives undertaken by the Government of India to address trafficking in persons. The problem of human trafficking, including child trafficking, is multidimensional and requires coordination between several ministries which remains a big challenge till date and is one of the main reasons that affects protection, prosecution and prevention of human Trafficking. For example, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA), Ministry of Labour, Ministry of Overseas Indian Affairs (merged with MEA in 2016), and Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) have to work together for successful handling. The MHA is the nodal agency for the implementation of the ITPA 1956 and other human trafficking initiatives, through its Anti-Trafficking Cell. The Ministry of Women and Child Development (MWCD) continues to be the nodal ministry for tackling this crime with respect to women and children and is also responsible for inter- ministerial coordination. In addition, The United Nation Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) Regional Office for South Asia (ROSA) has been involved in initiatives to address human trafficking in collaboration with the Government of India, particularly the MWCD and the MHA. However, in most cases there are reported lack of adequate platform that provide the required and timely coordination.

Inadequate AHTUs

In 2007 it was decided that Anti Human Trafficking Units be set up in all districts to investigate cases of trafficking. Anti-Human Trafficking Units or AHTUs continue to serve as the primary investigative force for human trafficking crimes. In reply to the question raised by Shri. Mohammad Ali Khan, Member, Rajya Sabha in the Winter Session of 2015, the Minister of State, Ministry of Home Affairs, Shri. Haribhai Parathibhai Choudhary mentioned 225 AHTUs were set- up during 2010-11 and 2011-12. However as per the information available on the Anti-Human Trafficking website of the MHA- http://stophumantraffi cking-mha.nic.in/ – the total number of the AHTUs set-up in the country in the years 2010-11 and 2011-12 add up to only 218.. Further, in the previous reporting period of 2016-17, MHA released funds to establish a total of 270 AHTUs out of the more than 600 districts of the country. MHA reported 264 AHTUs were operational throughout the country during the reporting period, an increase of five compared with the previous reporting period. Some NGOs reported significant cooperation with AHTUs on investigations and police referral of victims to NGOs for rehabilitation services. However, other NGOs noted some AHTUs continued to lack clear mandates and were not solely dedicated to anti-trafficking, which created confusion with other district- and state-level police units and in some cases impeded their ability to proactively investigate cases. Some police offices reportedly used AHTU resources and personnel for non-trafficking cases. Coordination across states remained a significant challenge in cases where the alleged trafficker was located in a different state from the victim. NGOs noted some police offices were overburdened, underfunded, and lacked the necessary resources, such as vehicles and computers, to combat trafficking effectively. NGOs noted some prosecutors and judges did not have sufficient resources to properly prosecute and adjudicate cases. State and local governments partnered with NGOs and international organizations to train police, border guards, public prosecutors, railway police, and social welfare and judicial officers.

Several studies have highlighted these constraints and it is high time that proper and focused investments are made to strengthen these units.

Lack of Timely and Reliable Data and Comprehensive Judicious Research

There is a huge gap in accessing reliable and timely data that could be used to strategise or to design interventions specific to the conditions of the source, transit or destination points. It is very important that vulnerability mapping of trafficking prone areas and districts be done in the states with the objective of prevention, awareness generation, provision of viable livelihood options to vulnerable families, extending various welfare and anti-poverty schemes of the government to remotest areas. Access to this data will also help in increased vigilance and plan well-coordinated rescue operations, identify risks involved for the victim/survivor in repatriation and restoration, and assess and create possibilities of community based rehabilitation programmes. It is also important that relevant data be sourced from agencies working across and consolidated at a nodal level. Currently, the NCRB is the only reliable source for data on human trafficking. There are ample research and real time evidence generated by civil society organisations. Compilation of these data at a centralised platform can provide useful inputs to design policies and programme interventions that will go a long way in effectively combatting trafficking.

Ineffective Institutional Response Mechanisms

Awareness and an effective response systems are essential for curbing trafficking of women and children. It is important that certain institutions especially at the source areas be targeted in a focused manner to create awareness on different aspects of human trafficking. Targeting schools, colleges and panchayats in a focused manner to be aware and vigilant and responsible to ensure the vulnerable groups, especially children, are safe and protected should be a primary strategy for the government.

Lack of Required Sensitivity

A humanistic approach to victims/survivors especially when rescued is most important. Yet, in most rescue operations we hear stories of insensitive treatment meted out to victims especially women rescued in raids in parlours, etc where they are very often charged with offence. While legal ramifications have to be complied by, it is important that we treat the victims with due sensitivities. This requires effective sensitization of all stakeholders, especially those who directly handle victims.

Poor Prosecution

The poor rate of prosecution and conviction is a cause of worry. It also hints at the lacunae at the investigating end. It is to this culmination that it is mandatory that training organisations at the Central and State levels should focus on sensitisation, dissemination of knowledge and training of ground level staff from the police, judiciary and women and child welfare departments. The extensive experience and knowledge base of field-based organisations can be very useful to achieve this purpose.

Inadequate Priority to Prevention

From an NGO’s point of view working on the issue of human trafficking and implementing projects on combatting the social malaise through ‘Prevention, Protection and Prosecution’ models, it has been noticed that although structures and systems are available to address the issue after the crime is committed, intervention on Prevention part is still underrated. Trafficking and migration remain inseparable as trafficking can be the unintended result of migration. People most importantly young people thrive and aspire for better life opportunities and would always have the urge to migrate. It is a human right and cannot be stopped. Therefore, important structures should be available in the source itself to prevent trafficking. Awareness among children/adolescents, communities, formation of effective structures such as Vigilance Committees/VLCP, children clubs and coordination between government agencies and communities should be assured.

Replication of Best Practices

There are major lessons that can be drawn from the efforts in rehabilitation. Appropriate shelter, timely psycho-social counselling, legal services and sustainable livelihood options remain the challenges for the last twenty years. There are best practices which need to be studied and replicated for effective solutions. In terms of services to the children, CHILDLINE 1098 service is widely accepted and applauded for providing services to children in distress. This has been possible through effective coordination between the State, its designated agencies and the NGOs. Some other services such as Integrated Child Protection Scheme, One Stop Centres, Swyamsiddha Scheme3 , Victim Compensation, Track Child, Khoya Paya, Railway Children Policy etc. are very effective models and schemes that have scope for replication and should be upscaled.

Conclusion

Each instance of human trafficking takes a common toll. Each crime is an affront to the basic ideals of human dignity, inflicting grievous harm on individuals, as well as on their families and communities. Yet, if it were possible to hold human trafficking up to a light like a prism, each facet would reflect a different version of the crime, distinct in context but the same in essence. Together they would show the vast and varied array of methods traffickers use to compel adults and children of all genders, education levels, nationalities, and immigration statuses into service in both licit and illicit sectors. Traffickers may be family members, recruiters, employers, or strangers who exploit vulnerability and circumstances to coerce victims to engage in commercial sex or deceive them into forced labour. They commit these crimes through schemes that take victims hundreds of miles away from their homes or in the same neighborhoods where they were born. Yes, there has been a lot of progress in addressing the issue in the last decade, but we still have a long way to go. Today, human trafficking features as a billion dollar business and is becoming more organized than ever before. With advancement in technology, the modus operandi of this organized crime is changing fast and requires an equally fast paced and effective response system. Combatting human trafficking is not any single agency’s responsibility. It requires a movement where every institution and every citizen equally participates to combat this gross violation of human rights.

Footnotes:

1 https://www.gaatw.org/books_pdf/Human%20Rights%20and%20Trafficking%20in%20Person.pdf

2 https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/organized-crime/intro/UNTOC.html

3 http://www.uniindia.com/bengal-govt-to-extend-swayangsiddha-scheme-to-all districts/states/news/1354993.html