Introduction

There are structural problems in the Indian employment situation. Our economic growth continues to be fairly high, but few new jobs are being created, leading to a situation of “jobless growth”. This is an immediate and vitally important challenge.

But lack of jobs is only one aspect of the problem. The quality of jobs is poor, and informality is increasing. The Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) is decreasing. Women, especially, are dropping out of the labour force. Finally, our productivity continues to be very low compared to other economies.

This set of circumstances has led to a gap: a few Indians who have been endowed with skills, wealth, and health, have thrived. Others, the vast majority, find themselves without productive and dependable employment. They may even find that the jobs which they do have are being automated and replaced. The scarcity of good jobs also leads to frustration, hopelessness, and distrust in the state. This may manifest through phenomena as diverse as farmer suicides, more demands for reservations, and communal/caste violence.

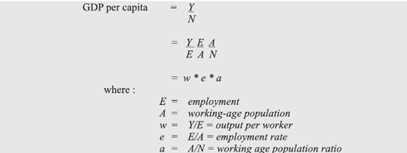

In this document, we study the structural issues relating to employment and growth in India, and propose policy steps to create large numbers of good jobs.1 The framework for analysis I use can be easily understood as follows.2 For an economy with income Y and population N, the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita is:

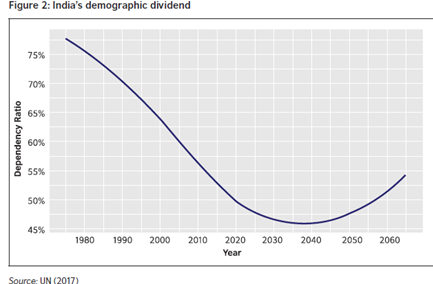

Thus, the per capita value added can be decomposed into the employment rate, the working age population ratio, and the productivity (output per worker). In India, there are issues with each of these. The rate of employment has been falling, and the productivity is low and continues to stagnate. The fraction of the population that is of working age is increasing and will be high till about 2040, but this demographic dividend will be foregone if adequate productive employment is not available.

This article is structured as follows. First, in section 2, we examine if it is true that India’s growth has been jobless, and the reasons why that has been so. We then consider why the employment rate has been decreasing. The next section, section 4 is on the demographic dividend: what it is, and why it is essential we make full use of it. In the next section, we consider labour productivity and how it can be increased. In section 6, we present an initial set of policy proposals aimed at improving the employment situation. The final section concludes.

Jobless Growth

Growth in aggregate production is usually associated with growth in total employment. However, there is no guarantee that economic growth will be labor intensive, nor that productivity gains will be shared by all workers.3 In India, we have been seeing a situation where economic growth has been reasonably strong, but new enough new jobs have not been created. This situation, called ‘jobless growth’, has led to high unemployment and increasing inequality. We need to create over 5 million jobs per year, just to maintain its employment rate.4 India’s GDP has been growing at a rate of 7.3% over the past four years,5 one of the highest growth rates in the world. This growth has also created jobs, but the increase in employment has not been commensurate with the increase in the labour force. During some intervals, there has even been a decline in jobs.6

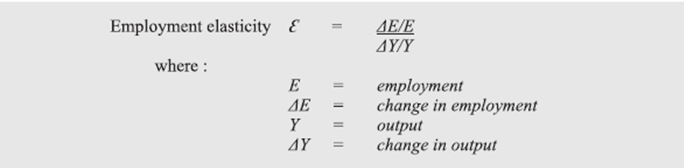

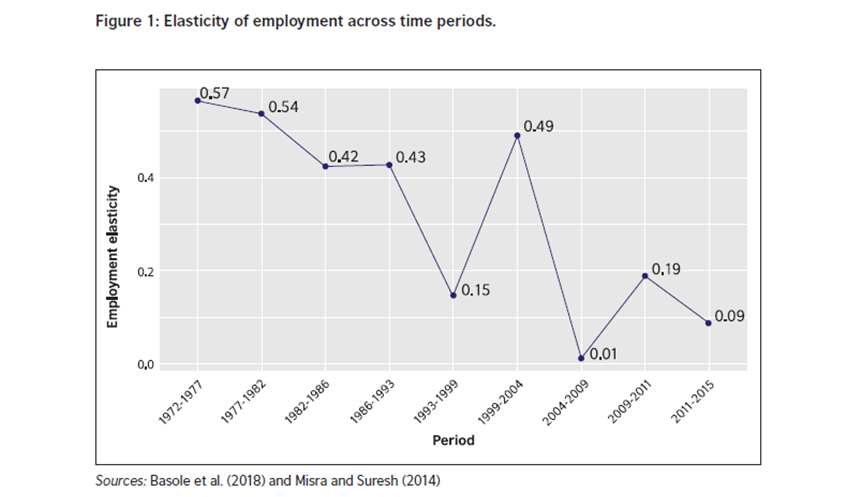

The divergence is clearly visible if we look at the employment elasticity. This is the percentage change in employment when the output rises by one percentage point.

Figure 1 shows that the employment elasticity has been declining over the past several decades. Now one percentage point growth in GDP increases employment by less than 0.1 percentage points.

The primary reason for the decline in the aggregate employment elasticity has been the decline in the employment elasticity of agriculture.7 This, coupled with the low growth of the agricultural sector, has meant that the sector has been shedding jobs.

Simultaneously, there has been substantial change in production technology. There has been a decline in labour-intensity in the organized manufacturing sector, especially in the labour-intensive industries. Within sectors, there has been a shift towards capital intensive production. Sectors that are capital intensive have been growing faster relative to the labour intensive sectors (Papola 2012). Sen and D. K. Das (2014) find that this has occurred due to a fall in the relative price of capital goods, driven by trade reforms in capital goods. Ramaswamy (2008)nds that there has been a shift in aggregate demand in favour of skilled labour as against unskilled labour, driven by restrictive domestic labour regulations as well as by trade openness.

Global trade not just decreases jobs requiring unskilled or semi-skilled labour, it also weakens the bargaining power of unskilled labour. Thus, the reasons for jobless growth include overly restrictive labour regulations, poor skills in the workforce, and trade openness.

Employment rate

The employment-population ratio in India is estimated to be about 51.75% in 2018, down from 58.31% in 1991.8 This number is low due to high unemployment and low participation in the labour force in the presence of a demographic dividend.

India, like many other low-income countries, suers from considerable structural under-employment. The large agricultural sector usually serves as a reservoir of under-employed labour, keeping open unemployment low. However, in the recent past, this trend has changed. The rate of unemployment is usually around 2%, but it is reported to have shot up to 6.1% is 2017-18, the highest in four decades.9

Labour laws can also impact the creation of jobs.10 The labour laws in India have traditionally privileged the rights of the employee against the opportunities of the unemployed. The protections granted to the employees were so strong as to reduce the possibilities of the creation of new jobs. Some states are now trying to reverse their path so as to encourage growth and employment.11

Manufacturing has historically offered the fastest path out of poverty. However, there is some evidence that premature de-industrialisation12 is taking place in India, closing o this avenue. Services may not be able to absorb our large population of unskilled workers.13

While skilling has received significant policy attention, progress in this area cannot be achieved overnight. Wages and productivity are diverging. Wage growth has been slower than the growth in productivity. Practices such as using contract workers, as well as leveraging capital-intensive technologies have put workers on the defensive.14 Further, manufacturers have been able to keep the bargaining power of labour low by leveraging trade.15

Compounding this high unemployment is the low participation in the labour force. The LFPR fell sharply from 43% in 2004-5 to 36.9% in 2017-18.16 There are two disturbing developments here: Firstly, the number of Not in Education, Employment or Training (NEET) youth is sharply increasing. As open unemployment increases, more people in the prime ages of their working life get disheartened and drop out of the labour market altogether. The second is the decline in the LFPR of women, which has been an ongoing trend.

In countries that are very poor, the LFPR is high—few can aord to stay out of the labour force. As countries become more prosperous, more and more people of working age start withdrawing from the labour force. This withdrawal may be for further education. Often, among women, a part of this withdrawal may be for domestic duties. As incomes rise further, a larger proportion of women are seen to work again. This leads to the famous U-shaped relationship between female LFPR and economic development (as approximated by GDP per capita).17

This curve has been plotted in the Infographic in this edition.18 The figures also contain the quadratic best-t curve. The female LFPR for India is far below the curve19 This supports the argument that the low LFPR in India is largely attributable to the drop of LFPR amongst women.20

Working age population

The fraction of Indian population who are of working age (usually considered 15 and above) is very high, compared to other countries. This is a double-edged sword: it could be a powerful positive factor in helping to raise incomes and develop faster, but if this phenomenon is not well utilised, it could also lead to a crisis.

At some point in the demographic development of any country, it reaches a point where the growth in the working-age population is greater than the growth in the total population. At this point, the country experiences what is called the “demographic dividend”. According to United Nations Population Fund,

The demographic dividend is the economic growth potential that can result from shifts in a population’s age structure, mainly when the share of the working-age population (15 to 64) is larger than the nonworking- age share of the population (14 and younger, and 65 and older).

With fewer dependents, and the largest section of the population in the working age, it is possible to generate more incomes, more savings, more capital per worker, and more growth. As a consequence of our demographic dividend, the dependency ratio, dened as the ratio of the non-working age population to the working-age population, is decreasing in India. Figure 2 illustrates how it will decrease till about 2040, after which it will again increase. This is India’s opportunity to achieve high growth and inclusive prosperity.

The demographic dividend will be realised only if we are able to provide the additional labour force with gainful jobs. If, instead, youth unemployment is peaking, the outcome may be worse than just the loss of an opportunity—large numbers of young people with no jobs and poor prospects are associated with outbreaks of violence.21

Labour productivity

India’s labour productivity growth averaged a dismal 1.7% in the 30 years between 1950 and 1980. It improved to an average of 3.8% in the next 20 years and shot up to an average 8% between 2005 and 2011, which were also India’s best growth years. Since 2011, labour productivity growth has started decelerating and the 4.3% growth posted in 2017 was much lower than what is required to sustain GDP growth in excess of 8%.22

Labour productivity is a function of human capital formation (education, skills, etc), the capital available (machinery, equipment) for each worker, and increase the overall efficiency of production embodied in Total Factor Productivity (TFP). As mentioned earlier, there is significant focus on human capital increase, through education, training and skilling. We have also seen above that capital is being increasingly deployed, in many cases replacing labour.

The TFP channel for increasing labour productivity depends on things like public capacity, institutional quality, and organisational methods. In India, the informal sector is a large part of the economy and continues to persist. The productivity in the informal sector is declining.23 Informalisation is increasing even in the formal sector. Firms are often observed to use contract workers (secondary workers and labor outsourcing) to stay below the legal threshold size to escape labor regulations.24 There is also evidence that tax regulations lead to small sizes.25

This informalisation of workers leads to poorer job quality.26 Smaller rms do not grow or generate employment, while the larger rms are much more productive, and employ far more people (La Porta and Shleifer 2008). Hsieh and Klenow (2009), using plant level data show that total factor revenue productivity increases with size more both in India and China.

Policy Proposals

So far, India has tried to tackle unemployment in many ways. We have a infrastructure of employment exchanges, large but of questionable utility. We have tried to enhance human capital through skill development. However, meaningful skill development takes time, especially starting from a low skill base as in the case of India. It is also possible that by the time people are trained, production technology might advance and change, requiring new skilling.

Many jobs have been generated through large-scale public works. Other policy interventions have include increasing labour mobility through better roads and transport systems, as well as promoting urbanisation. While all these continue to be important, they alone have not been able to solve the problem. In the sections below, some more concrete steps are suggested:

Job creation incentive

New jobs are associated with positive externalities:

Social externalities If society has preferences for reducing poverty and or inequality, sustainable jobs for poor people will have a social externality. Similarly, there can be social externalities linked to jobs for young men, which contribute to social stability. Jobs for young women can also produce externalities, by facilitating human capital accumulation in their children

Labor externality When many workers are unemployed or underemployed (which is the case in India), the economic opportunity cost of labor can be well below market wages. The difference between the market wage and the opportunity cost is a measure of the social benefit of not having labor resources idle.

Thus, there is a significant positive externality to creating jobs. So far, policy has tried to increase employment by promoting economic growth and by complementary steps such as skill development, infrastructure development, and urbanisation. In a sense, these are trickle-down policies. They do not focus directly on jobs, but the expectation is that growth will lead to more jobs. And just like trickle-down has not worked for growth or prosperity, it has not worked for employment either. It is time to take direct steps to promote employment.

We propose that employers be directly incentivised to create jobs. If a new, good job is created, the employer should be given a certain sum of money. This will directly reward employers who create new jobs.

It should be noted that the incentive is only for the creation of a new job. Once a job is created and filled, the employer will continue to employ the new employee only if they nd that value is added mutually.27

Industrial and trade policy

As indicated in Section 2, openness to trade has brought losses as well as gains to India. Given that the terms of trade and changing—incomes in China are increasing, and many bottlenecks in India such as overly stifling regulations, lack of connectivity, poor electricity and infrastructure, are easing, attempts should be made to use industrial and trade policy as a tool to attract more jobs and production to India.

In addition, it is clear that trade openness has played a key role. This operates in many ways:

- Goods previously produced here may now be imported, leading to loss of manufacturing and related jobs;

- Where production continues here, the labour may be replaced with imported capital goods, leading to loss of jobs;

- The remaining workers are subject to pressure and loss of negotiating power, due to the overhanging threat of being replaced by machines.

Thus, while trade openness has led to growth and prosperity, especially among the well-educated and skilled members of the workforce, it is also necessary to consider the costs associated with it, and to ask whether trade has also led to a decrease in prosperity among many vulnerable sections.

Social Protection

The recent amendment to the Maternity Benets Act mandates half a year of maternity leave. The act also requires a day-care facility in organisations with more than 50 employees, work-from-home options and a maternity bonus. Interventions such as these might actually end up reducing the employment of women. Imposing this burden entirely or even largely on the employer alone will dissuade employers from hiring women and reduce their pay.28 Costs such as these should be borne by the government, or at least shared by it.

Tax Policies

In India, income from Long-Term Capital Gains (LTCG) is generally taxed at a rate of 20%, after adjusting for inflation through indexation. LTCG on equity investments has been especially low. In fact, it was not taxed at all until recently.

Now, it is taxed at just 10% (without indexation). Dividends received from firms are taxed at about 17%. Thus, the eective rate of tax on capital gains income is quite low. In addition, wealth tax has been abolished and inheritance is also not taxed in India. In contrast, the return to labour (wages or salaries) are taxed at rate that can be as high as 30%.

This discrimination is sought to be justified by positing that since accumulation of capital leads to high incomes for labour, tax policy should encourage capital accumulation.29

While capital accumulation certainly should be encouraged, extreme tax bias towards capital and against labour can lead to a rentier society. Recent economic work has signaled the importance of higher taxes in income, wealth and inheritance, and also pointed out that many of the reasons for advocating zero tax on capital are awed.30

Conclusion

So far, India has focused on securing growth. The hope was that jobs will follow as a side-effect of growth. Thus, the primary focus was on securing growth through reforms, promoting market efficiency, and promoting capital accumulation.

This was sought to be helped along by supply-side interventions such as skilling, and matching interventions such as employment exchanges.

However, this has not been sufficient. The market, operating freely, will create a sub-optimal number of jobs because of externalities to job creation. The government will need to intervene to some extent to create more jobs. We have suggested that, in particular, the government should directly incentivise the creation of jobs by paying firms to create good new jobs. This will encourage labour-intensive growth rather than the currently seen capital-intensive growth. We have also given specific recommendations about how industrial and trade policies, as well as social protection and tax policies can be used together to create a job-rich growth environment.

Endnotes

1 By a “good job”, we mean a job characterised by formalised terms of employment, reasonable stability, safe working conditions, the right to unionize, and a pay rate that enables at least a lower middle-class lifestyle.

2 World Bank 2009.

3 Merotto, Weber, and Aterido 2018.

4 Mehrotra 2019.

5 IMF 2018.

6 Abraham (2017) shows uses the Labour Bureau’s annual household employment survey (Labour Bureau 2016) to reveal a decline in total employment from 446.39 million (2013-14) to 442.65 million (2015-16), a drop of 3.74 million jobs.

7 Basu and D. Das 2015.

8 WB 2018.

9 Jha 2019.

10 In this connection, Besley and Burgess (2004) had a strong impact. However, its conclusions have been challenged by Karak and Basu (2017) and Storm (2019).

11 MoLE 2015.

12 Rodrik 2015.

13 Amirapu and Subramanian 2015.

14 D’Costa 2017.

15 Amit and Nayanjyoti 2018.

16 Mehrotra 2019.

17 This was perhaps rst noted in India by J. N. Sinha (1967), but has since been seen widely (Mammen and Paxson 2000; Goldin 1994).

18 The data is sourced from World Bank Open Data, and corresponds to 2017.

19 Some of the reasons for this are explored in Mehrotra and S. Sinha 2017.

20 Beyer 2018.

21 For instance, see Benmelech, Berrebi, and Klor 2010.

22 Chakraborty 2018.

23 Maiti and Sen 2010.

24 Ramaswamy 2013.

25 Ramaswamy 2016.

26 Kapoor and Krishnapriya 2017.

27 Of course, further work is required to clearly dene what constitutes a new job, what jobs qualify as good jobs, how corruption and misuse can be prevented, and how this scheme can be implemented while not imposing unnecessarily onerous burdens on employers.

28 Chakraborty 2018.

29 The Chamley-Judd Redistribution Impossibility Theorem states that optimal tax rate on capital is zero. Also see Atkinson and Stiglitz (1976).

30 Piketty and Saez 2012.

References

Abraham, Vinoj (2017). “Stagnant Employment Growth”. In: Economic and Political Weekly 52.38.

Amirapu, Amrit and Arvind Subramanian (2015). Manufacturing or services? An Indian Illustration of a Development Dilemma. Working Paper 408. Center for Global Development.

Amit and Nayanjyoti (2018). Changes in Production And Labour Regimes and Challenges before Collective Bargaining: A Study Focusing on the Gurgaon-Neemrana Industrial Belt in the DMIC. Background Paper for State of Working India 2018

- Bengaluru: Azim Premji University.

Atkinson, A.B. and J.E. Stiglitz (1976). “The design of tax structure: Direct versus indirect taxation”. In: Journal of Public Economics 6.1, pp. 55–75.

Basole, Amit et al. (2018). State of Working India 2018. Bengaluru: Azim Premji University.

Basu, Deepankar and Debarshi Das (2015). Employment Elasticity in India and the U.S., 1977–2011: A Sectoral Decomposition Analysis. Economics Department Working Paper Series 190. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Benmelech, Efraim, Claude Berrebi, and Esteban F Klor (2010). Economic Conditions and the Quality of Suicide Terrorism. Working Paper 16320. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Besley, Timothy and Robin Burgess (Feb. 2004). “Can Labor Regulation Hinder Economic Performance? Evidence from India”. In: The Quarterly Journal of Economics 119.1, pp. 91–134.

Beyer, Robert Carl Michael (2018). Jobless Growth? Washington,D.C.:World Bank.

Chakraborty, Samiran (Feb. 23, 2018). “Why investment and productivity is key to India’s GDP growth”. In: Financial Express.

D’Costa, Anthony P. (2017). Point of No Return? Changing Structures and Jobless Growth in India. GPID Research Network Working Paper 7. Economic and Social Research Council.

Goldin, Claudia (1994). The U-Shaped Female Labor Force Function in Economic Development and Economic History. Working Paper 4707. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hsieh, Chang-Tai and Peter J. Klenow (2009). “Misallocation and Manufacturing TFP in China and India*”. In: The Quarterly Journal of Economics 124.4, pp. 1403–1448.

International Monetary Fund (2018). India: Gross domestic product, constant prices (Percent change). url: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2018/02/weodata/weorept.aspx?pr.x=49&pr.y=18&sy=2015&ey=2018&scsm=1&ssd=1&sort=country&ds=.&br=1&c=534&s=NGDP_RPCH&grp=0&a=#download.

Jha, Somesh (Feb. 1, 2019). “Unemployment rate at four-decade high: NSSO survey compared past gures”. In: Business Standard.

Kapoor, Radhicka and P. P. Krishnapriya (2017). Informality in the formal sector: Evidence from Indian manufacturing. IGC Working Paper F-35316-INC-1.

Karak, Anirban and Deepankar Basu (2017). Profitability or Industrial Relations: What Explains Manufacturing Performance Across Indian States? Economics Department Working Paper Series 217. University of Massachusetts Amherst.

La Porta, Rafael and Andrei Shleifer (2008). The Unofficial Economy and Economic Development. NBER Working Paper Series 14520.

Labour Bureau (2016). Report on Fifth Annual Employment-Unemployment Survey (2015–16). Ministry of Labour and Employment, Government of India.

Maiti, Dibyendu and Kunal Sen (2010). “The Informal Sector in India: A Means of Exploitation or Accumulation?” In: Journal of South Asian Development 5, pp. 1–13.

Mammen, Kristin and Christina Paxson (2000). “Women’s work and economic development”. In: Journal of economic perspectives 14.4, pp. 141–164.

Mehrotra, Santosh (Feb. 11, 2019). “The shape of the jobs crisis”. In: The Hindu.

Mehrotra, Santosh and Sharmistha Sinha (2017). “Explaining Falling Female Employment during a High Growth Period”. In: Economic and Political Weekly LII.39, pp. 54–62.

Merotto, Dino Leonardo, Michael Weber, and Reyes Aterido (2018). Pathways to Better Jobs in IDA Countries : Findings from Jobs Diagnostics. Jobs series 14. Washington, D.C.: World Bank.

Ministry of Labour and Employment (2015). Rajasthan Amendments in Labour Laws. Government of India. url: https://labour.gov.in/rajasthan-0.

Misra, Sangita and Anoop K Suresh (2014). Estimating Employment Elasticity of Growth for the Indian Economy. RBI Working Paper Series 6. Reserve Bank of India.

Papola, T.S. (2012). Structural Changes in the Indian Economy: Emerging Patterns and Implications. ISID Working Paper 2012/02. Institute for Studies in Industrial Development.

Piketty, Thomas and Emmanuel Saez (2012). A Theory of Optimal Capital Taxation. Working Paper 17989. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Ramaswamy, K.V. (2008). Wage inequality in Indian manufacturing: Is it Trade, Technology or Labour Regulations? Working Paper WP-2008-021. Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

– (2013). Size-Dependent Labour Regulations and Threshold Effects: The Case of Contract-worker Intensity in Indian Manufacturing. Working Paper WP-2013-012. Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

– (2016). Size Dependent Tax incentives, Threshold Effects and Horizontal Subcontracting in Indian Manufacturing: Evidence from Factory and Firm-level Panel Data Sets. Working Paper WP-2016-007. Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

Rodrik, Dani (2015). Premature Deindustrialization. Working Paper 20935. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Sen, Kunal and Deb Kusum Das (2014). Where Have All The Workers Gone? The Puzzle of Declining Labour Intensity in Organized Indian Manufacturing. Development Economics and Public Policy Working Paper Series 35/2014. Institute for Development Policy and Management, University of Manchester.

Sinha, J. N. (1967). “Dynamics of female participation in economic activity in a developing economy”. In: Proceedings of the World Population Conference, 1965. Vol. 4. Department of Economic and Social Aairs. New York: United Nations, pp. 336–337.

Storm, Servaas (2019). Labor Laws and Manufacturing Performance in India: How Priors Trump Evidence and Progress Gets Stalled. Working Paper 90. Institute for New Economic Thinking.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Population Division Social Affairs (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision – Special Aggregates.

World Bank (2009). Job Generation and Growth Decomposition Tool. Reference Manual and User’s Guide. Poverty Reduction Group, World Bank. World Bank (2018). Employment to population ratio, 15+, total (percentage) (modeled ILO estimate). url https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.EMP.TOTL.SP.ZS?locations=IN