The GSDP of the Chhattisgarh state for 2021-22 (at current prices) is projected to be Rs 3,83,098 crore. This is an annual increase of 5% over the actual GSDP of 2019-20, and 9.4% higher than the revised estimate of GSDP for 2020-21 (Rs 3,50,270 crore).

Trends in Revenues

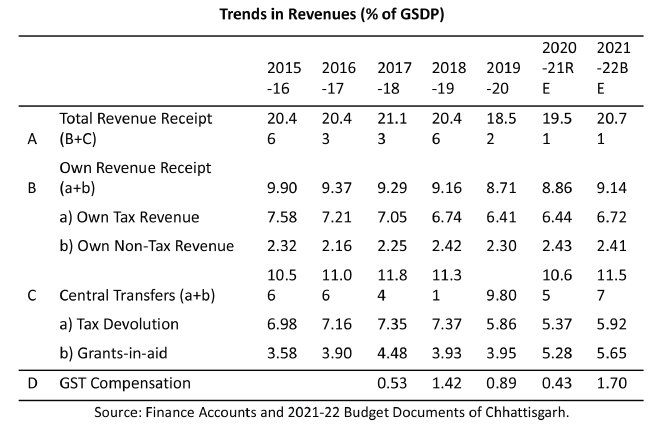

Total revenue receipts1 for 2021-22 are estimated to be Rs 79,325 crore, an annualised increase of 11 per cent over 2019-20. Of this, Rs 35,000 crore (44 per cent) will be raised by the state through its own resources, and Rs 44,325 crore (56 per cent) will come from the centre. Resources from the centre will be in the form of state’s share in central taxes (29 per cent of revenue receipts) and grants (27 per cent of revenue receipts). In 2020-21,total receipts (excluding borrowings) are estimated to fall short of the budget estimate by Rs 15,488 crore (decrease of 18 per cent). Revenue receipts decreased mainly due to decrease in receipts of share of Union taxes and duties by Rs 3253 crore.

In 2021-22, receipts from the state’s share in central taxes are estimated to register an annual increase of 6 per cent over 2019-20. However, as per the revised estimates of 2020-21, receipts from the state’s share in central taxes were estimated to have decreased by 30 per cent as compared to the budget stage. This was due to a 30 per cent cut in the Union Budget for devolution to states, from Rs 7,84,181 crore at the budgeted stage to Rs 5,49,959 crore at the revised stage.

State’s own tax revenue of Chhattisgarh is estimated to be Rs 25,750 crore in 2021-22, an annual increase of 8 per cent over the actual tax revenue in 2019-20. In 2020-21, as per the revised estimates, state’s own tax revenue is estimated to be 14 per cent lower than the budget estimates.

Analysis of finances of the State of Chhattisgarh reveals that own revenues of the state as percentage of GSDP has been declining during the period 2015-16 to 2020-21 RE. Own revenues as percentage of GSDP declined from 9.90 percent in 2015-16 to 8.86 percent in 2020-21 RE – a trend observed in many other states. Own revenues are budgeted to increase to 9.14 percent in 2021-22 BE. The main reason for the decline in own revenues is the decline in own tax revenues of the state which fell from 7.58 percent of GSDP in 2015-16 to 6.44 percent in 2020-21 RE. In 2021-22 BE, the tax revenue as percent of GSDP is budgeted to increase to around 6.72 percent. The tax buoyancy assumed for 2021-22 is around 1.51 as compared to the achieved buoyancy of own tax revenues of 0.55 during 2017-18 and 2020- 21RE. Although the fall in own taxes is cushioned by GST compensation, but this is a short term arrangement as GST compensation is for a 5-year period and will stop after June 2022. Own non-tax revenues which account for about 25-26 percent of own revenue receipts of Chhattisgarh more or less remained stable fluctuating within a narrow range of 2.2 to 2.4 percent during this period. Most of the revenues from non-tax sources (around 78-80 percent) is from non-ferrous mining and metallurgical industries.

Central transfers comprising devolution and grants-in-aid from the Union government account for about 55 percent of the total revenues of that state in recent years. Between 2017-18 and 2019-20 central transfers to Chhattisgarh as percent of GSDP fell from 11.84 percent to 9.80 percent, a fall of more than 2 percent of GSDP on account of fall in both devolution and grants (which includes GST compensation from 2017-18 onwards) from the Union government. This corresponds to the period when the national GDP growth contracted from 11.03 percent to 7.75 percent (in nominal terms).

Thus on the revenue side we find that own tax revenues (as % of GSDP) have been falling cushioned by GST compensation. With the subsuming of nine state taxes into GST, state governments are left with limited own tax handles. The benefits of migration to GST are yet to be seen. GST revenues are yet to stabilize and there are issues of settlement of Integrated GST and delays in the release of GST compensation to states. Furthermore, with the 5-yesr GST compensation period ending in June 2022, this stream of revenues will cease.

The State has to raise revenues from current sources and also explore other sources to meet its expenditure commitments going forward. We examine the scope for that below. Revenue receipts /GSDP and revenue receipts (RR) per capita are better values as compared to RR in absolute terms. For instance, per capita RR of Chhattisgarh was around Rs. 22000/- in FY 2020, higher than neighbouring MP but lower than Maharashtra, Telangana, etc. However, w.r.t. RR/GSDP, Chhattisgarh is much higher than states like AP, Maharashtra, Telangana and Tamil Nadu. However, what is of concern is that RR/GSDP has been declining over the years.

We may emphasise this, as it means that the revenue is not keeping pace with GSDP growth, or that the Government is using debt increasingly to balance the Budget. The growth rate of Revenue Receipts, Own Tax Revenue (OTR) and the growth rate of Non-Tax Revenue (NTR) has been declining steadily. In 2019-20, the Revenue Receipts actually fell by 1.88 per cent compared to the previous year.

Trends in Expenditures

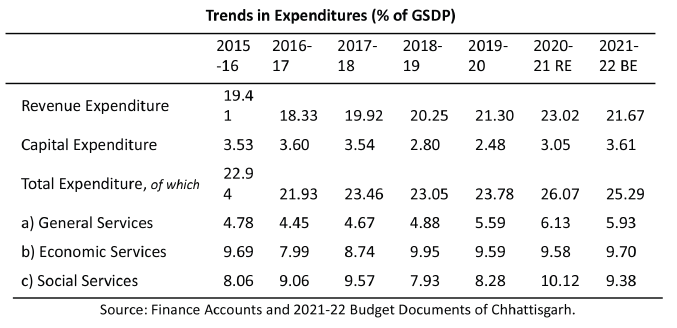

On the expenditure front we find that revenue expenditure as percent of GSDP increased from 18.33 percent in 2016-17 to 21.30 percent in 2019-20 and further to 23.02 percent in 2020-21RE. The capital expenditure however, declined from 3.60 percent to 2.48 percent of GSDP between 2016-17 and 2019-20, a fall of about 1.12 percent of GSDP. In 2020-21 RE, it is expected to increase to 3.05 percent of GSDP and is budgeted to further increase to 3.60 percent of GSDP in 2021-22BE. Total expenditure as percentage of GSDP increased from 21.93 percent in 2016-17 to 26.07 percent in 2021-21RE and is budgeted to be around 25.29 percent in 2021-22BE.

Services-wise disaggregation of total expenditure show that while expenditure on general services as percentage of GSDP has been increasing since 2016-17, expenditures of social services which includes expenditures on education, health, family welfare, etc. declined from 9.57 percent of GSDP in 2017-18 to 8.28 percent in 2019-20. However, there was an increase in expenditures on social services in 2020-21RE. Social services expenditure increased by about 24 percent between 2019-20 and 2020-21RE. In other words the government of Chhattisgarh has been spending more on medical and public health, education and various programmes of social welfare at the time of the pandemic. Expenditure on Medical and Public health show as jump of around 40.5 percent in 2020-21RE vis-a-vis 2019-20.

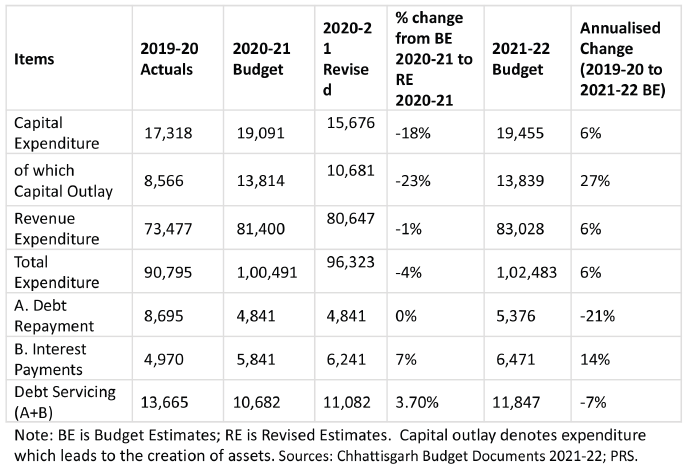

Total expenditure for 2021-22 is estimated to be Rs 1,02,483 crore, a 6 per cent annualised increase over the actual expenditure in 2019-20. Revenue expenditure for 2021-22 is proposed to be Rs 83,028 crore, which is an annualised increase of 6 per cent over 2019-20. This expenditure includes the payment of salaries, pensions, and interest. Revenue expenditure in 2019-20 increased primarily due to increase in interest payment on Market loans (Rs 138 crore), Pension and other retirement benefits (Rs 1,209 crore), General Education (Rs 3,470 crore) and Food, storage and warehousing (Rs 1,629 crore). The sectors of Rural Development (17 per cent), Police (9 per cent), and Transport (4 per cent) saw the highest increase in allocations.

- Committed Expenditure (CE) which is salaries, pensions and interest payments, has grown from Rs 33,373 crore (45.42 percent of revenue expenditure) in 2019-20 to Rs 39,192 crore to 47.2 per cent of BE FY21-22, which means nearly half of the revenue is going towards CE rather than newer development activities.

- The state’s revenue expenditure is budgeted to increased by a mere 2.95 per cent in FY21-22 compared to the previous financial year and an annualised increase of only 6 per cent over 2019-20.

- Chhattisgarh’s capital outlay for FY21-22 is estimated to be Rs 13,839 crore, which is an annualised increase of 27 per cent over 2019-20.

Expenditure on Subsidies during 2015-20

Subsidies as a percentage of Revenue Receipts increased from 4.40 per cent in 2018-19 to 5.19 per cent in 2019-20 and constituted 17.98 per cent of the revenue receipts and 15.63 per cent of the revenue expenditure

The expenditure on subsidies sharply increased by Rs 3,160 crore (37.96 per cent) from Rs 8,323 crore in 2018-19 to Rs 11,483 crore in 2019-20. The main components of this during the year were

- Finance (Rs 2,729. crore) for Agricultural Loan Waiver Scheme.

- Food and Civil Supplies (Rs 4,938 crore) for Chief Minister Food Assistance Scheme and for meeting losses on Food Procurement,

- Energy (Rs 3,074 crore) for free supply of electricity to Agricultural Pumps, Single Bulb Connection relief in Electricity Fees and

Capital expenditure of the State showed a significant decline during the years 2018-19 and 2019-20, with a decrease of Rs 1,098 crore in 2018-19 and Rs 337 crore in 2019-20. CE decreased by 3.79 per cent in 2019-20 compared to the previous financial year. In a reversal of this trend, capital expenditure for 2021-22 is proposed to be Rs 19,455 crore, which is an annual increase of 6 per cent over the actual expenditure in 2019-20.

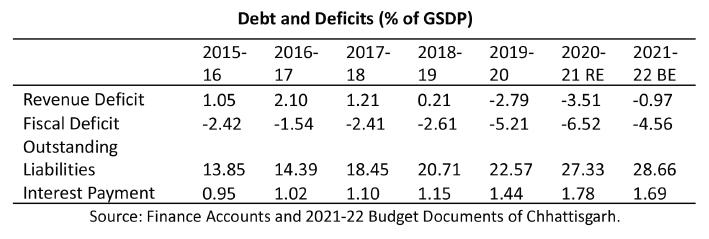

Debt-Deficit Indicators

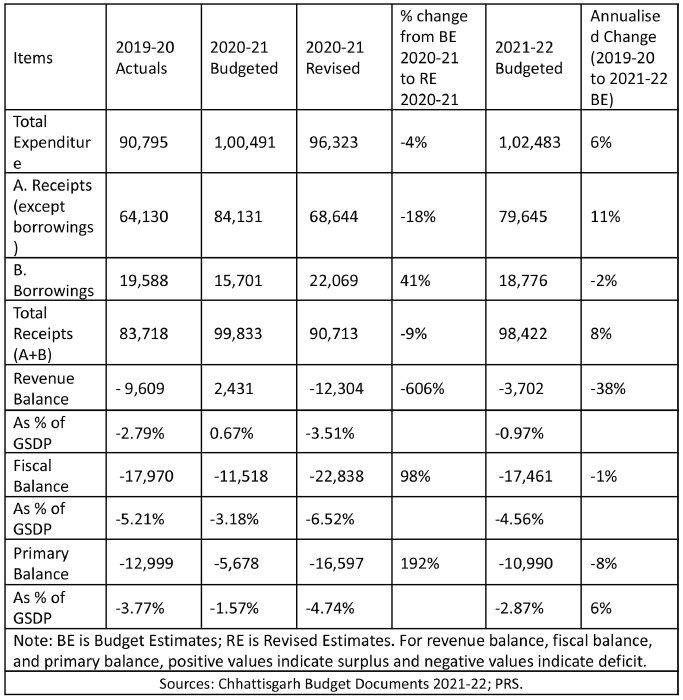

Revenue deficit for 2021-22 is estimated to be Rs 3,702 crore, which is 0.97 per cent of the GSDP. In 2020-21, as per the revised figures, revenue deficit was estimated at Rs 12,304 crore (3.51 per cent of GSDP).

Fiscal Deficit increased during 2019-20 to Rs 17,970 crore from Rs 8,292 crore in 2018-19, since the State had turned from a revenue surplus of Rs 684 crore in 2018-19 to a revenue deficit of Rs 9,609 crore in 2019-20. During 2019-20, Fiscal Deficit at 5.46 per cent of the GSDP exceeded the target prescribed (3.50 percent of GSDP) in the FRBM Act. In 2020-21, the revised estimate for fiscal deficit was expected to be 6.52 per cent of GSDP, higher than the budget estimate of 3.18 per cent of GSDP. Fiscal deficit for 2021-22 is targeted at Rs 17,461 crore, which is 4.56 per cent of GSDP.

From the examination of key deficit indicators of the state we see that Chhattisgarh had surplus on the revenue account during the period from 2015-16 to 2018-29. However, in 2019-20 the state had a revenue deficit of 2.79 percent of GSDP which increased to 3.51 percent in 2020-21RE. The state had budget for a revenue deficit of about 1 percent of GSDP in 2021-22BE. There is a high possibility of slippage in meeting the budgeted revenue deficit numbers as the improvement is largely due to the increase in transfers from the central government as also increase in own tax revenues of the state. Such increase in transfers from the central government and own revenues that has been assumed for 2021-22BE may not materialize given the ongoing pandemic situation and past performance of own tax revenues.

The fiscal deficit percentage of GSDP was well below the 3 percent level during the period from 2015-16 to 2018-19. However, in 2019-20, the fiscal deficit increased to 5.21 percent of GSDP breaching the FRBM target of 3.50 percent of GSDP. In 2020-21, the revised estimate for fiscal deficit was 6.52 per cent of GSDP as compared to the 2020-21 budget estimate of 3.18 per cent of GSDP. This increase can be partly attributed to the additional borrowing of 2 percent of GSDP allowed by the Union government to states as part of the Atmanirbhar Bharat package over and above the mandated borrowing limit of 3 percent of GSDP. Fiscal deficit is budgeted to be around 4.56 percent of GSDP in 2021-22BE.

The 15th Finance Commission had allowed a borrowing limit of 4 percent of GSDP to states for the fiscal year 2021-22. Chhattisgarh can avail additional borrowing space of 0.50 percent of GSDP every year during 2021-26 if it undertakes power sector reforms recommended by the 15th Finance Commission. The power sector reforms proposed by the 15th Finance Commission can create additional fiscal space for higher capital spending which will have positive effect on growth.

The total outstanding liabilities of government of Chhattisgarh as percentage of GSDP has been rising from 13.85 percent in 2015-16 to 27.33 percent in 2020-21RE and is budgeted to further increase to 28.66 percent in 2021-22BE. As a result the interest payments as a percent of GSDP show an increasing trend, increasing from 0.95 percent in 2015-16 to 1.78 percent in 2020-21RE. It is budgeted to be around 1.68 percent in 2021-22BE.

State Government Borrowings

The outstanding debt of the Government of Chhattisgarh (henceforth, GoCG) was Rs 78,712 crore at the end of 2019-20. This was 23.6 per cent of the GSDP in that year. As per the FRBM Act 2003-04, the States are advised to keep the total Outstanding Debt below 20 per cent of GSDP. The period since 2012-13 has seen a continuous increase in the debt level of the GoCG and that has now reached almost 25 per cent of GSDP which was the limit prescribed by the 14th Finance Commission.

In 2021-22, expenditure on debt servicing is estimated to be Rs 11,847 crore, an annual reduction of 7 per cent over 2019-20. In 2020-21, revised estimate for debt servicing is 3.7 per cent higher than the budget estimate.

The 15th Finance Commission recommended the following fiscal deficit targets for states for the 2021-26 period (as a per cent of GSDP):

(i) 4 per cent for 2021-22,

(ii) 3.5 per cent for 2022-23, and

(iii) 3 per cent for 2023-26.

The Commission estimated that this path will allow Chhattisgarh to increase its total liabilities from 28.1 per cent of GSDP in 2020-21 to 31.6 per cent of GSDP in 2025-26. If the state isunable to fully utilise the sanctioned borrowing limit as specified above in any of the first fouryears, it can avail the unutilised borrowing amount in the 2021-26 period.

Additional borrowing worth 0.5 per cent of GSDP will be allowed each year for the first four years (2021-25) upon undertaking certain power sector reforms including: (i) reduction in operational losses, (ii) reduction in revenue gap, (iii) reduction in payment of cash subsidy by adopting direct benefit transfer, and (iv) reduction in tariff subsidy as a percentage of revenue.

Government Borrowing Under RIDF

The Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) is one of the most economical borrowing instrument @2.75 per cent. Loan to be repaid in equal annual instalments within seven years from the date of withdrawal, including a grace period of two years. However, the GoCG is yet to leverage this facility optimally.

As per the NABARD website as on 31 Aug 2021, a total of 8318 projects were financed through the RIDF borrowings, with a sanctioned loan amount of Rs 4969.74 crore, and the amount drawn was Rs 4254.43 crore. The largest categories of projects were for water resources, for which a total of Rs 257. 4 crore was drawn and solar powered pumps for which a total of Rs 430.74 crore was drawn. It is recommended that the GoCG should enhance its borrowings under the RIDF.

As per latest RIDF Policy, the normative allocation is decided on certain factors which are favourable to Chhattisgarh. The corpus announced for each tranche is allocated among different States as per “Normative Allocation” based on certain parameters.

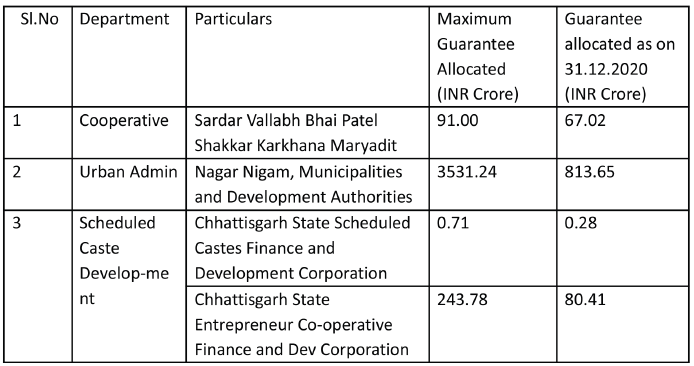

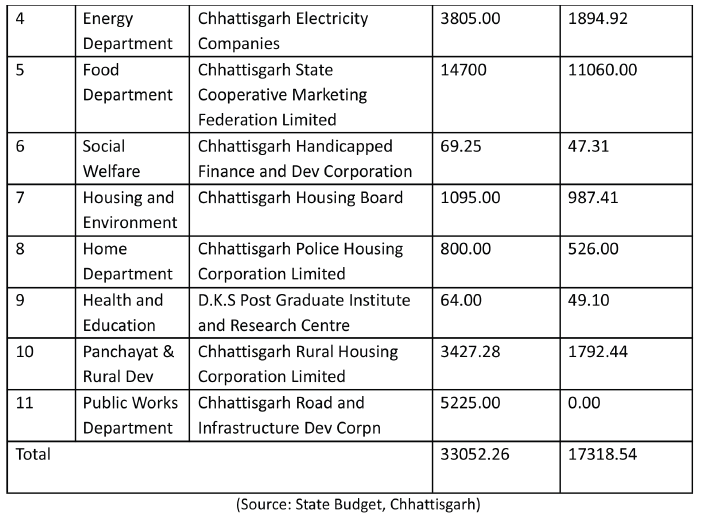

Guarantees issued by Chhattisgarh State Government

In addition to direct borrowing by the GoCG, it has also provided guarantees to various state government bodies and corporations to borrow from other financial institutions. If any of the primary borrowers are not able to service their loans, the guarantee will devolve to the GoCG and cause additional demands on its fiscal resources.

Suggestions for Improving the Fiscal Health of the State

Revenue receipts have gone down as a percentage of the GSDP and this trend needs to be reversed. The state needs to adopt various measures to mobilise additional resources to improve its fiscal parameters in line with the targets specified by the Finance Commission and Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management (FRBM) Act projections.

Farm loan waivers and paddy procurement at a bonus price above the MSP were the two major reasons for the fiscal deficit. However, given the income and welfare enhancing effect on farmers of paddy procurement at a remunerative price, the measures may have to be continued. However, the GoCG should get an impact assessment study done of this measure to see if the benefits are commensurate with or higher than the fiscal cost.

Further, the procured paddy may be disposed on a national e-marketing platform, so that buyers from all over India, including exporters, can bid for the paddy and the State Government agencies then get a remunerative price. Further, the unsold paddy can be used to establish a paddy value chain all the way up to ethanol, so that more employment is generated along with GSDP growth.

The next important reason was free or concessional electricity supply. As the 15th Finance Commission has already stated, if the state does away with this, the state will have an opportunity borrow 0.5 per cent more of its GSDP.

The State government should review and analyse the reasons for delays in capital projects and take efforts to complete them quickly. Last milestone projects should be taken care of to reap the benefits of the investments already made in those projects. An institutional mechanism should be established, on the lines of the Union government’s PRAGATI, to monitor the progress on these capital projects. Such a forum should be chaired by Hon’ble Chief Minster and the Chief Secretary and all the key departmental Secretaries should attend this meeting on a quarterly basis.

Using borrowed funds for meeting current consumption and repayment of interest on outstanding loans was not sustainable in the long run. Borrowed funds should be utilised to create assets to stimulate growth. Interest payment has drastically increased as compared to the previous year due to addition of the market loans of Rs 10,980 crore during the year 2019-20. Using borrowed funds for meeting current consumption and repayment of interest on outstanding loans is not sustainable in the long run and would impact creation of assets. If indeed the state needs to borrow, it should first tap funds from concessional sources such as the RIDF of NABARD.

There are a number of funds available from the Government of India, over and above the normal grants in aid. These include funds like the allocation of mining royalties to the District Mining Foundations (DMF), funds from the Compensatory Afforestation Fund Management and Planning Authority (CAMPA), the Universal Services Obligation Fund (USOF) for providing telecom services to underserved areas. The amounts under these are significant and the GoCG should establish a cell in the Finance Department to draw the maximum amount that the state is eligible to get under these funds.

Measures for Mobilization of Investment for GSDP Growth

While the Government’s financial resources are seen as a major policy and developmental instrumentality, the fact is that the Government’s share of the GSDP (Rs 1,02,483 crore) is just about one quarter (26.7 per cent) of the GSDP (Rs 3,83,098 crore). Thus the rest of the GSDP comprises of the cumulative expenditure of the household and the corporate sector, and savings, which are almost entirely by the household sector. The ability of the government to spend or invest more is constrained by the fiscal deficit. Thus we have to look at financial resources from the household sector and the corporate sector.

A vast majority of the savings come from the household sector and are used for individual investments in consumer durables, livestock, land, house property, equipment and vehicles. Thus these “savings” do not appear in the numbers of the banking or financial sector, since it is done mostly by households on their own account. Instead some of this appears as consumption expenditure (except land and house property).

The second source of investment is corporate investment, mobilised by the corporate in the form of equity or debt from the capital market, almost always from outside the State. For this the source is financial savings instruments like insurance and pension linked savings, shares, mutual funds, etc. which are funded by household financial savings.

Enhancing Household Savings

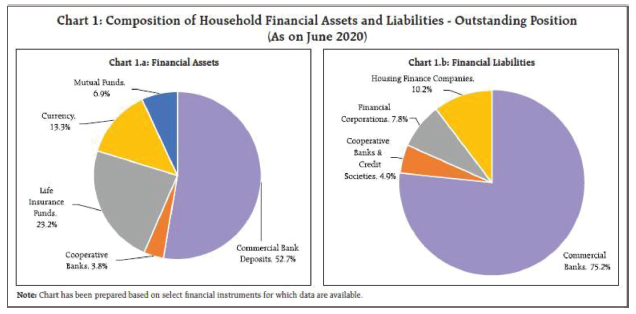

As per the RBI, household financial savings in India are significantly affected by their deposits with and borrowing from the banking sector2. Bank deposits and bank loans constitute dominant shares of around 56 per cent and 80 per cent of household financial assets and liabilities, respectively. See Chart below:

Domestic savings rate, particularly that of households, is critical as it determines the quantum of funds available for governments and corporates to borrow from. Indian households account for about 60 per cent of the country’s savings, but this is falling gradually. Lower domestic savings exposes borrowers to overseas markets, weakening India’s external position and raising external debt.

India’s savings rate had touched a 15-year-low as gross domestic savings stood at 30.9 per cent of GDP in FY20, down from a peak of 34.6 per cent in FY12. Household savings fell from 23 per cent of GDP in 2012 to 18 per cent in 2019. In Q2 of FY21, increased household consumption, particularly its discretionary component, could be attributed to a resumption in economic activity following the easing of the lockdowns. The reversal in household financial savings is corroborated by the lower surplus in the current account balance. Household debt to GDP ratio rose sharply to 37.1 per cent in Q2, from 35.4 per cent in Q1.3

To the extent household savings are deposited in banks, bank credit becomes a source for investment, both for individuals as well as for corporates. But this is a small fraction of the overall household savings. This is because the financialization of household savings is still quite modest in the state, with households preferring to save in the form of jewelers, land, livestock, house property, durables, vehicles, etc.

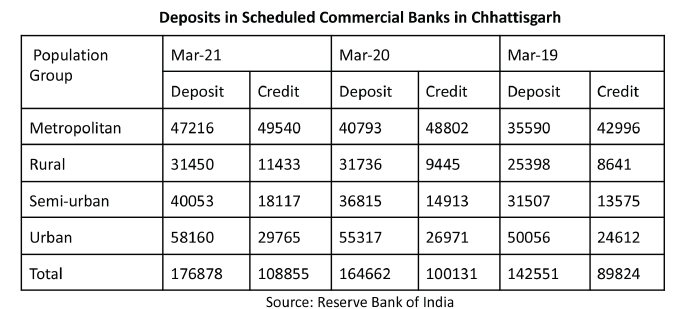

Deposits grew by about Rs 12,216 crore to Rs 1,76,878 crore, from Mar 2020 to Mar 2021. What is interesting is that even out of this meagre financial savings of Rs 12,216 crore in the year, only about Rs 8725 crore or about 71 per cent of the savings were deployed as incremental credit in that year, the rest going out of the state economy. So there is a vast gap between what is needed and what is available for deployment through the banking sector.

Increasing Bank Credit and Institutional Finance

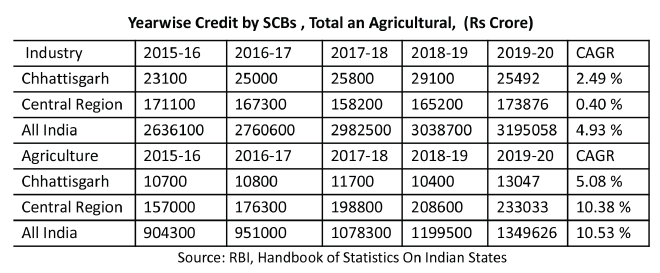

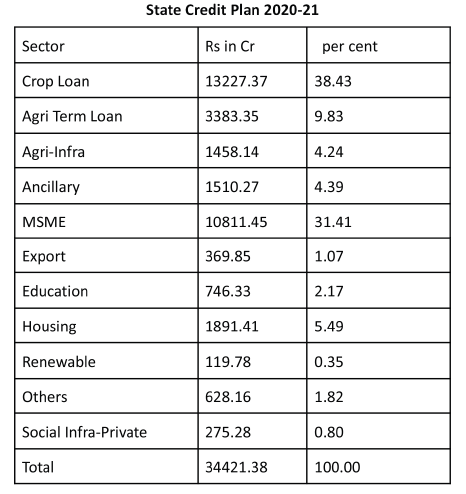

The State Focus Paper produced by NABARD4 puts the credit potential of the state at a modest Rs 36,260 crore, which though higher than the State Credit plan target by about 10 per cent, is nowhere near what it should be.

As per the state credit plan for 2020-21, the total credit deployment target was Rs 34,421 crore. As per the SLBC5 , the target for 2021-22 is Rs 41,914 crore. However, credit deployment figures can be misleading, since they do not talk about the amount recovered during the year and thus do not represent the net increase in credit outstanding. As per the RBI data above, the incremental credit outstanding for the year was only Rs 8725 crore. On the whole, the bank credit outstanding of Rs 108,855 crore represents only 30 per cent of the GSDP and is a low Credit/GSDP ratio.

If the credit/GSDP ratio were to be taken even to the all India average of about 50 per cent from the current 30 per cent in five years, it would mean an additional deployment of 20 per cent of the GSDP in 2020-21, or Rs 72,000 crore and the GSDP will go up in the meanwhile. Assuming it goes up by about 50 per cent in five years, the additional credit deployment would be about Rs 108,000 crore, doubling credit outstanding in five years.

The Credit Deposit (CD) Ratio of banks in 2019 was 63.3 per cent, a good 15 per cent below the national average of 78.3 per cent. The flow of investment credit to agriculture and other sectors is particularly inadequate. The recent changes in PSL Norms incentivizing SCBs/ RRBs to lend in credit starved districts by assigning 125 per cent weightage in such districts (Chhattisgarh has 15 such districts) needs to be highlighted.

The below table indicates the below average growth of credit for both agriculture as well as industry in the State. The CAGR is almost half that of the national average.

Financing Growth at the Base of the Pyramid – SHGs and MFIs

There is ample scope for financing of Women SHG Groups in Chhattisgarh in the Micro Enterprises sector. There is a felt need for bankers and the GoCG should work with themto enhance the SHG culture among tribal women of Chhattisgarh and extend liberal finance to enable them to take a foothold in income generating activities. The GoCG should take up an SHG-Bank linkage program on a war footing through the SRLM and other agencies which work with SHGs, such as PRADAN, MYRADA & APMAS.

There is ample scope for financing of Women SHG Groups in Chhattisgarh in the Micro Enterprises sector. There is a felt need for bankers and the GoCG should work with them to enhance the SHG culture among tribal women of Chhattisgarh and extend liberal finance to enable them to take a foothold in income generating activities. The GoCG should take up an SHG-Bank linkage program on a war footing through the SRLM and other agencies which work with SHGs, such as PRADAN, MYRADA and APMAS.

From the point of view of the lower income groups, microfinance institutions (MFIs) are an important source of funds. As per MFIN data6 , as on 30th Sep 2020, there were 14 MFIs active in the state, with loan outstanding of Rs 1811 crore. This was rather low compared to Rs 6005 crore in neighbouring Odisha and Rs 4774 in Madhya Pradesh. Thus it calls for a concerted strategy for the state government to attract more MFIs to come and work in the state. The GoCG should approach the MFI industry associations, namely MFIN and Sa-Dhan for this purpose.

The GoCG should encourage households to invest in those activities which help them diversify their income sources and generate a good rate of return. There are a number of sub-sectors such as diversified crop cultivation, animal husbandry, micro food-processing, handloom and pparel making and other household industries, repairs, local transport, hotels and restaurants, business and personal services, including homestay tourism, in which households could invest their savings and get a good income as well as a return on their investments. This will also enable them to protect their savings from getting eroded by inflation, which discourages people from making bank deposits.

From the point of view of the lower income groups, microfinance institutions (MFIs) are an important source of funds. As per MFIN data7 , as on 30th Sep 2020, there were 14 MFIs active in the state, with loan outstanding of Rs 1811 crore. This was rather low compared to Rs 6005 crore in neighbouring Odisha and Rs 4774 in Madhya Pradesh. Thus it calls for a concerted strategy for the state government to attract more MFIs to come and work in the state.

Increasing Corporate investments

Chhattisgarh as an investment destination has many plus points. A cursory glance at them suggest the following

- Pro-active administration with efficient law and order situation; no Labour unrests

- Attractive Industrial and Sector specific policies

- Excellent Infrastructure- Uninterrupted power supply with zero power cut situation

- Highly skilled industrious human resources with presence of premier institutes

- Enabling ecosystem- (Hospitals, Schools, Shopping Malls, Hotels and Real Estate)

- Cost Advantages: Cost of Living and Rent index low as compared to other States

As per the IBEF, Chhattisgarh is making significant investment in industrial infrastructure. Chhattisgarh State Industrial Development Corporation (CSIDC) has set up industrial growth centres, seven industrial parks and three integrated infrastructure development centres (IIDC). The state has a notified special economic zone (SEZ) in Rajnandgaon District. As of February 2020, the state had two formally approved SEZs. Total merchandise exports from Chhattisgarh were US$ 2,320.29 million in FY21. Combined export of aluminium and products, iron ore, and iron and steel products reached US$ 1,037.19 million in FY21. Nonbasmati rice, iron & steel and aluminium products are the main exports, contributing 20.46%, 14.92% and 13.93%, respectively, to the state’s merchandise exports.

The Chief Minister has made trips to USA and north East India to talk to investors and explore possibilities of bringing investments to the state, in sectors spanning – information technology, agro and food processing, biofuels, textile, pharmaceutical, Ayurveda and service industries. On a multi-city visit to US in early 2020, the chief minister talked of the new industrial policy 2019-24 of the state during a business meet with US India Strategic Partnership Forum at New York. He also met select investors at San Francisco apprising them the state’s strong focus on technology-based enterprises.

Thanks to such efforts, in 2020-21, Chhattisgarh managed to be in the top 10 list of states with more private investment in the manufacturing sector in the third quarter of 2020-21. Chhattisgarh received Rs 10,228 crore investment projects between October and December 2020 as per a report by Projects Today. In the last two and a half years, the Chhattisgarh government has signed a total of 104 MoUs for setting up industries in the state with a proposed capital investment of more than Rs 42,000 crore. These industries will generate 64,000 new employment opportunities for the youths.

According to Projecx Survey data, across the states during July-September 2020 period (Q2FY21) among major states, Chhattisgarh and Tamil Nadu have topped the table when it comes to attracting new investments overtaking Maharashtra, Gujarat, Karnataka and others. Chhattisgarh topped the table by attracting fresh investment of Rs 35,771.3 crore in the form of 114 projects. The Rs 22,653 crore Bodhghat Irrigation project and a couple of mining projects worth Rs 8,197 crore by South Eastern Coalfields helped Chhattisgarh top the investment table in Q2 of 2021. This trend needs to be continued with good footwork.

Recommendations for Enhancing Investment in Chhattisgarh

The budget for 2021-22 indicates a capital outlay, that is, expenditure which is to be made by the government to create assets such as roads, bridges, airports, etc., of Rs 13,839 crore, which is a welcome 27 per cent rise over the amount of Rs 10,681 crore of capital outlay in the previous year.

However, as the state government has an overall budget constraint, GoCG should try to access other sources for capital outlay including the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank, bilateral lenders like JICA and specialized Indian term lending institutions such as NABARD, SIDBI, REC, IREDA and the India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited.

- The state government needs to work with the banking system to massively increase credit deployment in the state. The credit deposit ratio of the state needs to be steadily increased, from the current 70 per cent to 90 per cent or even higher than 100 per cent, like many of the states in southern and western India, as per RBI data. 8 The GoCG should work with banks to take the State CD (credit deposit) ratio on a year by year basis.

- The GoCG should ask banks to draw upon refinance from NABARD, which is available at 3 per cent for the PACS as MSC Scheme, Watershed and Wadi Schemes, and at 6 per cent for the Micro Food Processing schemes.

- The GoCG should build up the SHG-Bank linkage program through coordination with among the SRLM and the banks and MFIs in the state.

- For enhancing credit flow to micro-entrepreneurs who are shunned by banks, the GoCG should approach the MFI industry associations, namely MFIN and Sa-Dhan for this purpose.

- As not all households with financial surplus can invest in income-generating activities of the above kind, the GoCG as well as private players should encourage households to invest their savings in financial investments such equity mutual funds, which tends to fetch them higher returns and enables them to protect their savings from getting eroded by inflation, as happens to bank deposits.

In any case, as we know, the growth in the economy comes from investment, and a relatively small portion of that comes from the government. Thus for growth in the GSDP, we need to look at investments from the household sector directly and indirectly through their savings in banks which are leant to the private corporate sector, to supplement its own equity resources.

The role of the corporate sector in bringing in large investments is critical. Corporate investments require friendly policies and incentives. The GoCG should examine its policies and incentives from time to time to remain an attractive destination for corporate investors.

Footnotes:

1 We have cited extensively from the Chhattisgarh Budget Analysis 2021-22 by PRS India.

2 https://www.rbi.org.in/Scripts/BS_ViewBulletin.aspx?Id=19895

3 https://www.newindianexpress.com/business/2021/may/29/post-lockdown-boost-in-spending-pushes-q3-household-financial-savings-to-81-per-centof-gdp-2309287.html

4 https://www.nabard.org/plp-guide.aspx?id=699&cid=698

5 http://slbcchhattisgarh.com/pages/views/leadbankscheme_acp_targets

6 http://slbcchhattisgarh.com/pages/views/leadbankscheme_acp_targets

7 http://slbcchhattisgarh.com/pages/views/leadbankscheme_acp_targets

8 https://m.rbi.org.in/scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=18230