Abstract

“The law of nations was not concocted by ‘bookworms’, ‘ jurists’ or ‘professors’ , but was created and elaborated by the deeds of statesmen diplomats , generals , and admirals .”This statement of the celebrated English jurist, Professor Holland, appears very much true, when attention given to the achievements of the first Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru. Being a world statesman, he projected India’s constitutional vision of international order, which reflects in the doctrine of Panchsheel, as five principles of peace. The aim of this paper is to study, in general, Nehru’s contribution the maintenance of peace, good neighbourliness and the idea of moral conduct in international relations.

To keep this paper within limits, it addresses two objectives: First, a survey of the Constituent Assembly debates in order to provide an account of the thoughts of the framers the Indian Constitution and to find out how far Nehru’s ideas influence the drafting of articles relating to India’s international relations; and Second, an evaluation of the concept of Panchsheel that characterizes the development of International Law in Asia.

It is also felt useful to take this opportunity to note Nehru’s idea of peace and the Asian phase of his political thought. It will be concluded that Nehru’s Panchsheel message reflected India’s constitutional vision of world order, and it will be further submitted in respect of the doctrine that the contribution has, at least, the normative level, strengthened the regime of the principles of International Law and peace. The paper is divided into four parts. The first part deals with Nehru’s constitutional vision; the second discuss his idea of peace and the third analyses the doctrine. Finally, the fourth part is the conclusion.

Nehru’s Constitutional Vision of International Order

Though the end of World War II is seen as a turning point in the history International Law because of a shift of emphasis from war to peace, the ‘pioneering enterprise’ of substituting constitutional commitments for the use of force in the conduct of international relations began during the inter-war period. After the devastation of the world holocaust of 1939-45, peace and security became security became the chief concerns of international law and organization. The phrase “maintenance of international peace and security’ appeared as the first and the most important purpose of the United Nations Charter, while the development of friendly relations, international cooperation and harmonization of the actions of nations were the other purposes.

India’s constitutional vision of international order is traced in Article 51 of its Constitution, where it is stated that the “State shall endeavour to

(a) promote international peace and security;

(b) maintain just and honourable relations between nations;

(c) foster respect for International Law and treaty obligations in the dealings of organized peoples with one another; and

(d) encourage settlement of international disputes by arbitration.”

Article 51, in the present form, was adopted by the Constituent Assembly on 25 November 1948. When the Constitutional Adviser, Sir Benegal Rao had issued on 2 September 1946, two notes on the subject of fundamental rights for the use of the members of the Assembly, Part A of the note contained seven clauses – the first clause having been taken from the Declaration of Havana (1939) that:

The state shall promote international peace and security by the elimination of war as an instrument of national policy, by the prescription of open, just and honourable relations between nations , by firm establishment of the understandings of international law as the actual rule of conduct among governments and by the maintenance of justice and the scrupulous respect for treaty obligations in the dealings of organized people with one another.

The draft clause was discussed by the Sub-Committee on Fundamental Rights, and the Advisory Committee on Minorities and Fundamental Rights, etc., during April-August 1947. The words ‘by the elimination of war as an instrument of national policy’ were deleted from the draft clause and the draft article 40 of the draft constitution was tabled in October 1947 for consideration.

By a simple amendment to the draft, B.R Ambedkar divided the original text into three parts separating each from the other so that the article could give a complete idea of what consensus appears to have prevailed in the Constituent Assembly that India’s international relations be based on peace. However, some Assembly members approached the same idea but from different perspectives. Firstly, it was held by K.T. Shah that international peace cannot be established unless an open and frank declaration of policy – pledging a nation unreservedly to peace, to the maintenance of International Law and friendship – was given. According to him, international peace was a first step towards progress in an all-round disarmament.

Secondly, Mahavir Tyagi who had, in fact, argued for a militarily strong India, supported Shah. He was of the opinion that no one would care nor would any one listen to India unless it was strong. To fight for a cause of peace, a road to disarmament was required. Tyagi advocated that the future government of India be given directive in that regard, if the laudable objective of international peace was to be achieved.

Thirdly , B.H. Khardekar said, while discussing the positivist-naturalist controversy on the nature of International Law, that the law of nations was neither a panacea nor a chimera but an evolutionary process. From this perspective, there were, he observed, great expectations from India to develop International Law.

Fourthly , another member, Damodar Swarup Seth critically evaluated the draft article and found that it had ignored some fundamental issues like political and economic emancipation of the oppressed and backward peoples. He was the only member who moved a substantive amendment to Ambedkar’s text on draft article 40. “It shall also promote the advancement of the oppressed and backward peoples and the international regulation of the legal status of workers with a view to ensuring a universal minimum of social rights to the entire working people.” But the proposed amendment was not accepted. The Ambedkar division of draft article 40 was accepted with a few minor modifications in certain words.

Lastly, the suggestion of Ananthsayanam Ayyangar was agreed upon by the members and a new clause on encouragement “of the settlement of international disputes by arbitration” was added to the text. The sentiments expressed in the Assembly also reflected the country’s traditional culture concerned with peace. It was expressed that it was only India in the world, which can with ancient culture, spiritual heritage and centuries old tradition of non-aggression lay the foundations of international morality. To support, the reference was made to the mission of peace right from the thoughts of Ram Tirth Paramhansa and Swami Vivekananda down to Rabindranath Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi.

This exercise of looking back into the history of the drafting of Article 51 of the Indian Constitution, clearly reveals that Nehru had not participated in the Assembly debate on India’s constitutional vision of international order. It was only the speech on the Resolution Regarding Aims and Objects of the Assembly , 13 December 1946, where we find him moving a resolution, including therein paragraph 8 that: “This ancient land attains the rightful and honoured place in the world and makes its full and willing contribution to the promotion of world peace and the welfare of mankind.” He had asked the framers of the Constitution to bear that larger international aspect in mind as India had, on the verge of independence, begun to play an important role in international affairs. Perhaps for this reason, it has been observed that Nehru’s world perspective and vision of the future role of India in world affairs must have exercised on the minds of the framers. It was natural for these directives, therefore, to find a place in the Constitution.

There is no gainsaying the fact that Article 51 is a pledge that India will work for the promotion of world peace and security, enhancement of International Law and treaty obligations and settlement of its differences with other countries by peaceful means. Paranjpe writes that it was only Article 51 in Chapter IV of the Constitution of India that has been implemented to the fullest expression through the foreign policy of India. It does not only lay down what India is expected to do, it also states the limitations within which this country has to play an important role in international relations. To quote BishwanathDas: The role is honest; the role is upright; the role is open. There is nothing hidden in our ways.

Nehru’s Idea of Peace

In an attempt to evaluate India’s crusade for Panchsheel in the world, and particularly in Asia, it would not be correct to overlook the significance of Nehru’s ideas of peace and the Asian phase of his political thought. Nehru had begun taking interest in international relations since his participation in the Conference of the League Against Imperialism held at Brussels in February 1927. Earlier, he was so much in Indian politics that he could not show much interest in international problems. According to Michael Brecher, the Brussels Conference proved to be a turning point in the development of his political thought and gave him a broad international outlook.

After his return from the Conference, he observed on 13 September 1927, that it was difficult for India, during foreign domination, to develop an independent external policy. But the League Against Imperialism had offered a general line of future policy of which India should take full advantage of. Nevertheless, he was cautious that India should not confine to the framework provided by the League. He had no intention to dance to the tune of the League; his final break with it came in April 1936.

Nehru wrote in an article that an independent India would address its future role in international affairs to “world against Imperialism and its offshoots.” According to him, the foundation of peace meant the elimination of Imperialism, Colonialism and Racialism and the dominance of one country or people or another. Nehru was “an arch rebel and an angel of peace.” If, on the one hand, he was of the opinion that the colonized countries should revolt (if possible, by non-violent means) against their colonial masters, he also held that international peace and order could only be maintained by the principles and practice of mutual tolerance and non-aggression.

He knew that a fixed pattern of international behaviour, if pursued in the light of pre-colonial experience, would be totally different from what was relevant in the contemporary international order. Therefore his message to the Constituent Assembly was that of international peace and friendly relations and not the message of anti- Colonialism and anti- Imperialism. At a state banquet, in his honour by the Chinese Premier at Peking, Nehru said that peace was a way of life, thinking and action. It was a state of mind.

On another occasion, he expressed that whenever one desired peace, “one must think of peace and prepare for peace, instead of thinking of war and preparing for war” To him peace was not an absence of war; it could only be preserved by the methods of peace. The goal cannot be achieved by condemnation or mutual recrimination’ but rather by creating an environment of peace. He expressed his concern about the complex and overwhelming problem of the day, that the language of war was being used to promote peace. Therefore, he insisted on developing the temper of peace.

This approach was not new to India. It came into being with the teachings of Lord Buddha as early as the sixth century B.C., when a common heritage was provided to Asian countries and they were linked by Buddhist civilization. In a speech in the United States’ House of Representatives and the Senate on 13 October 1949, Nehru had commented that India had stood for peace throughout its long history and that “every prayer that an Indian raises, ends with an invocation to peace.” The basis of India’s foreign policy was, according to him, “to plead for and endeavour to practice. . . a binding faith in peace and an unfailing endeavour of thought and action to ensure it.” India in fact, has always been, since the ancient times, a peace loving country and has never desired aggression and expansion in its relation with other countries.

There is, no doubt, a great measure of truth in the fact that a country’s external policy reflects its cultural traditions and has domestic roots; the role of Indian cultural traditions of peace and non-aggression in India’s foreign policy can be emphasised more and more, but we should not forget that our philosophical and religious thoughts also bear evidence that India has produced a political thinker like Kautilya. Though certain principles of International Law were applied in inter- state relations, it is also true at the same time that the “racial expansion, religious differences and personal ambitions” had brought wars of aggression resulting in the rise and fall of many empires in different states in India. Nonetheless, it cannot be denied that mutual tolerance and non-aggression were preached from time to time in this country, and in the post-independent days’ Indian history, traditions and philosophy were extended into the external relations of India.

Being a world statesman and man of cosmopolitan outlook, Nehru was not a pacifist like Mahatma Gandhi and his views on international peace and affairs exercised more influence than any other politician. His views were twenty years ahead of many leaders of the world. Though an idealist, Nehru could visualize as to what was possible in international relations and what was not. Vincent Sheean has characteristically defined his policy as “The pursuit of peace – when possible”, which had appreciable result of such a nature that India came on better terms at that time with China, the Soviet Union, the United States and other big powers, than they were with each other. All that he tried to do was to be of some service in the preservation of peace, the idea inherited from India’s past.

Nehru’s Intellectual Make-up

Since Nehru was so much responsible for shaping the foreign policy of India it becomes important to keep in mind the realm of his thought to arrive at a correct understanding of India’s international relations. It is no exaggeration to say that all credit for formulating external policy of independent India be given exclusively to Nehru. He had assumed the role of “the philosopher, the architect, the engineer and the voice of his country’s policy towards the outside world.” But this should not mean that his personality and thoughts had so much influence that the foreign policy could be termed his “private monopoly.”

There were a number of different cross-currents in Nehru’s intellectual make-up. Almost all the ideological currents- Classical Liberalism, Fabian Socialism, Gandhian message for non-violence, Marxist theory of classless society, ethical norms of western humanism, the precepts of Vedanta, and the ancient system of the Hindu philosophy “appealed at various stages in his growth of intellectual maturity.” Brecher submits that none of these dominated his outlook nor could they be systematically integrated by Nehru into a consistent personal and political philosophy, as he was “an eclectic in intellectual matters.”

Nehru has been generally portrayed to be an idealist, because he was, according to some writers, “not adequately aware of security and power factors” and many weaknesses of his external policy were attributed to it. But some other writers have found him a realist. However, Misra correctly submits that it was unfair to place Nehru either in an idealist or realist category. To quote him: “In a sense, he was both, and yet in another sense, he was neither of the two. … It would lead to better understanding if it is realized that he constituted a category for himself, in which he combined the finer elements of both.” Nehru had tried “to harmonize and balance beneficial elements of idealism with his basic realist approach” because idealism to him was the realism of tomorrow. Nehru’s idealistic realism can be found in his deviation from a substitute for an alternative to the traditional power-oriented approach which did not ignore the realities of power but rejected power politics.

Being a realist, Nehru recognised power and security factors of India for the purpose of national defence and not for developing armaments as an instrument of power against other countries. As an idealist, Nehru made efforts to shape the international events with a view to ease the cold war tension without resorting to power politics. It can be said that India under Nehru’s leadership has tried to adapt the theory to reality in so far as she could and at the same time it brought a touch of her idealism. Nehru was not a pure idealist. He used to refer that India’s national interest was an important determinant of his foreign policy. He was very much critical of the pure realist view of international politics based on military and economic power. He supported “the idealist political tradition of modern India and the Gandhian insistence on non-violent and right means in particular, as an important element of India’s foreign policy.

Asian Phase of Nehru’s Political Thought

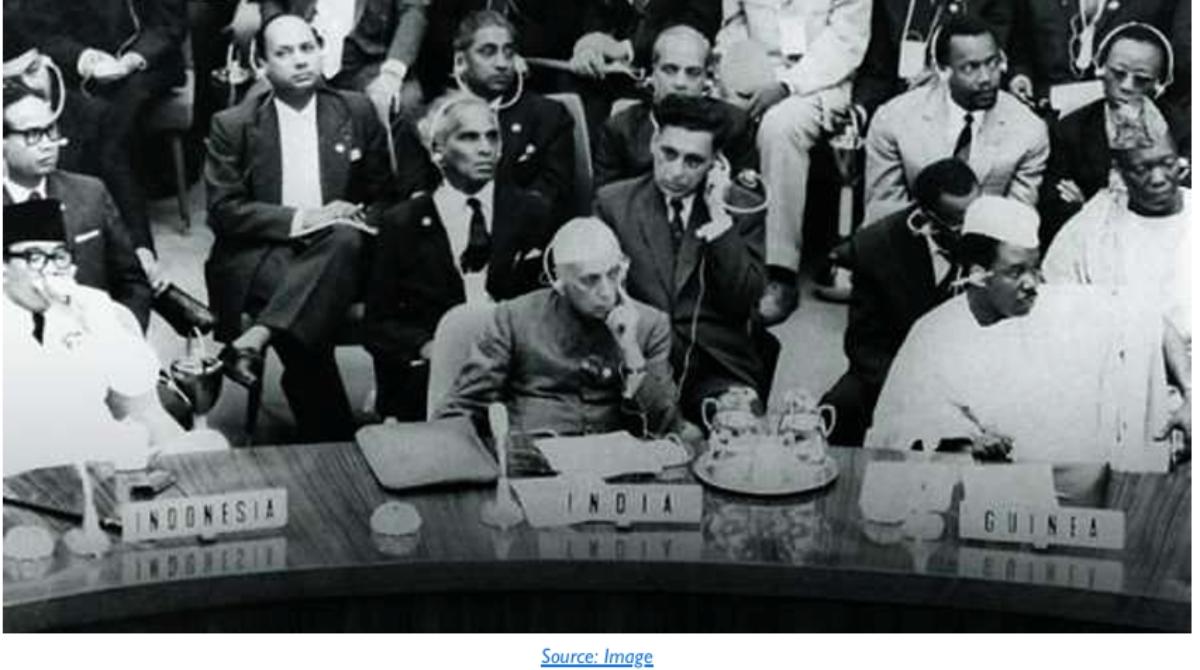

Pan-Asianism was an article of faith in Nehru’s policy. An origin of this phase of his political thought is traced from his idea of peace and his participation in the Conference Against Imperialism in 1927. In a Report on the Conference dated 19 February 1927, he had mentioned a strong desire of delegations from Asian countries right from the beginning of the Conference that some sort of Asiatic Federation was needed. A feeling of togetherness among the Asian countries was due to a recognition of a common bond of unity among them. Ten years after the League Against Imperialism, he addressed the Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi on 27 Mar 1937 and said that Pan-Asianism was not directed against Europe or America. He made it clear that the Pan-Asian Movement was a design to promote peace all over the world. However, the Bandung meet of 1955 was the high point in Pan-Asianism.

Keeping in view that the geography of international law had radically changed, and it was no logger the exclusive preserve of European blood, Nehru strongly believed that the unity of Asian countries was very essential for a new world order. The Asian countries had gained their right place on the world stage after a too long subordination under the European Powers, and this incident agitated Nehru’s mind that he began to think of a permanent peace in Asia which would alone be capable of banning war altogether from the world. In a burst of enthusiasm, he addressed the concluding session of the Asian-African Conference at Bandung that Asia had been passive enough in the past, when it had tolerated submissiveness for a long period. Asia was now no longer passive and submissive; it was dynamic and full of life. He interpreted others to Asia and Africa, and interpreted Asia and Africa to others. Therefore, President Nasser of the United Arab Republic had commented that Nehru was “the finest example of mutual interpretation.”

Throughout the 1950’s and 1960’s, a number of collective self-defence alliances had been concluded on ideological basis. International Law was, at that time, more concerned with the rivalry between the Communist and the non-Communist countries. Against this background, the main problem of the day, Nehru felt, was how to avoid war, relax international tension and lessen the grip of cold war, when the two hostile blocs were out to destroy each other. Since fear was the basic cause of war, the chief question was ultimately to end that fear. Establishment of the “right psychological climate” to remove that fear was the only means that Nehru wished.

Many Western international lawyers held a pessimistic view about International Law after World War II. Most of them had predicted a crisis in International Law, due to the emergence of the newly-independent countries in Asia and Africa. The new states were, according to them, not going to accept the law in the formation of which they had not participated, and the anti-colonialist rebellion was likely to shake the foundations of traditional International Law. A doubt was expressed that the states would consider the law as an alien system imposed on them by the European states. While expecting such a crisis, H.A. Smith asserted in 1947 that the very roots of International Law – the Eurocentric culture, legal traditions and common convictions – were being threatened. However, Chou Geng-Sheng observed that the pessimistic views “had warrant neither in theory nor in fact.”

Nehru was very much opposed to the oppressive, imperialistic, colonialistic and exploitative principles, but he did not reject traditional International Law. He always emphasized that there must be intercourse between nations and no nation had a choice except to subscribe to the principles and rules of international peace which were necessary for its regulation. India explicitly acknowledged, perhaps for this reason, the effectiveness of International Law in its Constitution, and it was mentioned in Article 51(c) that the State shall foster respect for International Law. It was, undoubtedly, an unquestionable acceptance of the validity of and respect for International Law. But the Constituent Assembly did not discuss which of the four positions with regard to traditional International Law – total rejection, total acceptance, partial acceptance and eclectic selection – would be accepted by an independent India. The question still remains unanswered whether they were aware that rejection of International Law could imply a denial of rights accorded under the Law, or a replacement of traditional International Law was impossible to be achieved at that time.

However, Nehru knew quite well that the Asian states were not prepared to reject traditional International Law in its entirety. The Asian countries would need a system of norms which would help in establishing an orderly and just society in Asia at various levels of growing intensity of their communications. It was easier for the Asian countries, in this background, to accept without any objection, the ideas of territorial integrity, non-intervention, non-aggression, sovereign equality, reciprocity and peaceful settlement of disputes. Thus Nehru created a climate of dedicated endeavour and moral aspiration and which he had thought would become an enduring feature of India’s international relations. He regarded that Panchsheel was India’s special contribution towards creating that climate which in the words of Burke, “demanded nothing from its converts beyond a verbal affirmation of five well-worn cliches.”

The Concept of Panchsheel: Formulation and Reaffirmation

The principal taking off point of the Nehru era of Indian f policy has been the concept of Panchsheel, the five foundations of peace. The doctrine represented a catalogue of “cardinal general principles in abstracto whose ultimate source was believed to be found in Indian history and philosophy. There were three objects behind the concept: first being the positive objective, to establish a peaceful climate where international tension be relaxed; the second , a negative objective to the futility of the recourse to violence and hatred; and finally, the objective that a power-vacuum, created in the Asian states by the withdrawal of imperialist powers, may not induce the other big military powers to extend spheres of influence in that area.

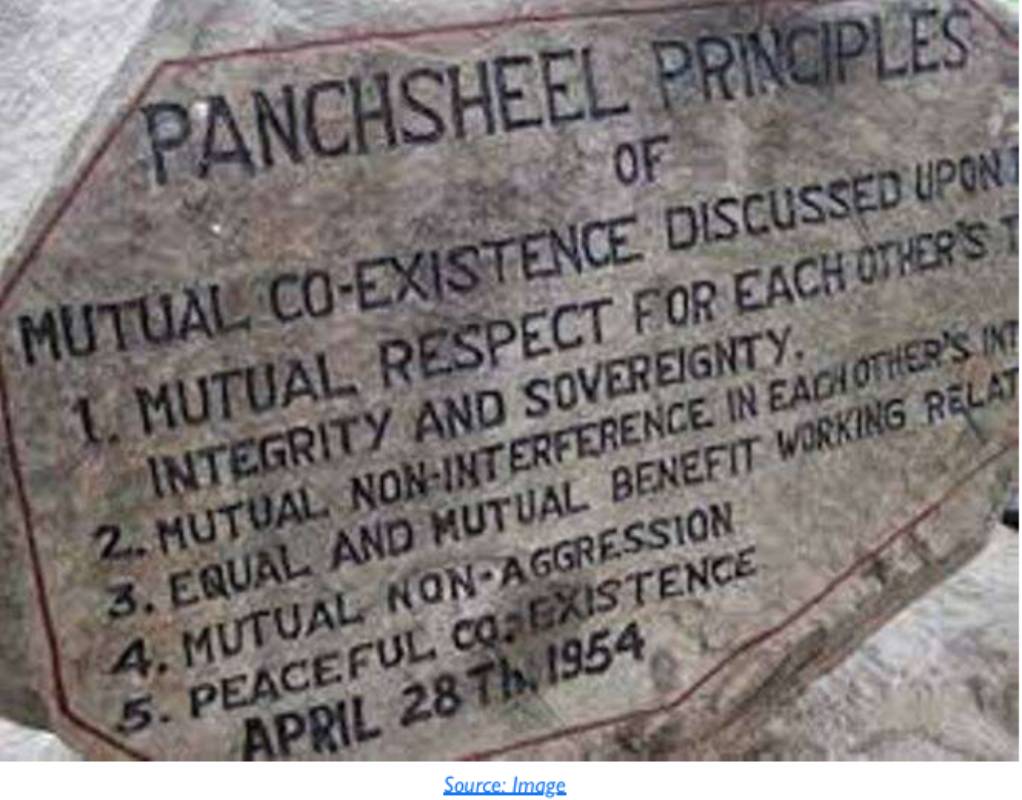

The idea of Panchsheel was given precision and formal seal of recognition on 29 April 1954, when the Five Principles were first given expression in a five-point preamble to an agreement between India and {he People’s Republic of China – “On Trade and Intercourse Betwęen Tibet Region of China and India.” Though the agreement concerned with the establishment of trade agencies in India by China and in Tibet by India and recognition of pilgrims’ travels in and other matters, the agreement included in its preamble principles, which are known as Panchsheel :

- Mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty ;

- Mutual non-aggression

- Mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs’

- Equality and mutual benefit , and

- Peaceful co-existence

Speaking in Parliament on the pact with China, Nehru called the preamble “the major thing about the Agreement”, and further added that many problems of the contemporary world might disappear “if these principles were adopted in the relations of various countries with one another.” An adherence to these principles created an “area of peace” between India and China, and Nehru wished that the area of peace was “spread over the rest of Asia and over the rest of the world.”

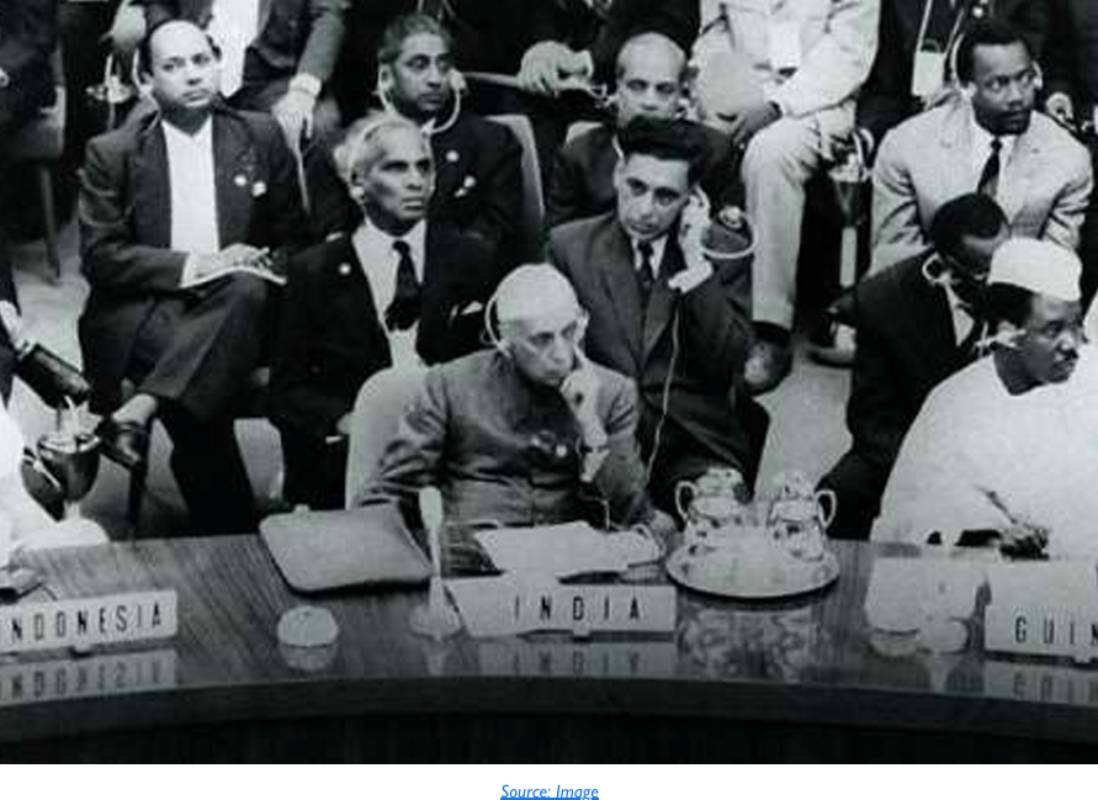

During 1954-56, Nehru visited twenty-six countries and hosted forty-one Heads of State, Heads of Governments and foreign ministers with the message of Panchsheel. As a result, the principles were adhered to, by the end of 1956, by a number of countries like Afghanistan, Burma, Cambodia, Egypt, Indonesia, Laos, People’s Republic of Mongolia, Nepal, Poland, Saudi Arabia, the Soviet Union, Democratic Republic of Vietnam and Yugoslavia; the term Panchsheel became an ‘international coin’. The principles were reaffirmed in the Asian-African Conference held in the West Java city of Bandung in Indonesia on 18-24 April 1955. Having been sponsored by “the Colombo Powers” – India, Burma, Ceylon, Indonesia, and Pakistan – the Conference was attended by twenty-nine countries of Asia and Africa.

Despite “strenuous pleading”, Nehru could not make the leaders of twenty-eight countries to agree to limit themselves to Panchsheel. The final communique of the Conference included a most significant document “Declaration on the Promotion of World Peace and Cooperation”, in which ten specified principles were listed with an expectation that they would regulate the relations of the nations of the world with each other. It must be noted that a reference to peaceful co-existence was completely omitted, while the right of collective defence was included. However, Nehru welcomed the clause relating to collective defence in the Bandung Declaration and did not express any objection to it. The reason stated was that the Declaration had referred to self-defence in terms of Article 51 of UN Charter where the inherent right of individual or collective self-defence against a member of the UN until the Security Council had taken measures for the maintenance of international peace and security.

Nehru claimed that the Bandung Declaration had embodied the Five Principles and an addition to the ten specified principles had reinforced Panchsheel. The principles were not, according to him ‘divine commandments’ nor was there any sanctity about their number or particular formulation. He considered the achievement of the Conference as epoch making. He had observed that it was a misreading of history to treat Bandung as an isolated occurrence. A more correct view he said was to see it as “a part of a great movement of human history”. Ever since its inception, Panchsheel has been endorsed by world statesmen and it has been regarded in the West as a central creed of India’s foreign policy.

Since Panchsheel had emerged from the Sino-Indian Pact over the Tibet Region of China, the names of Nehru and Chou En-lai are associated with it. The Chinese Communist sources associate the name of Prime Minister U Nu of Burma along with the names of the Indian and Chinese Premiers. It is interesting, however, to note that in an interview with Brecher, Krishna Menon mentioned the name of T.N. Kaul, the then Indian Ambassador in Peking, who was responsible for the mooting of the concept of the Five Principles. The principles were, for the first time, termed as Panch Shila by K.M. Pannikar in a broadcast talk over the All India Radio on 28 July 1954. But the word Panchsheel found its first expression by Nehru in his speech in Indonesia on 23 September 1954.

While in Indonesia, Nehru had in fact, heard the words ‘ Panch Shila ‘ used but in a different context. Its Indonesian interpretation – meaning thereby nationalism, internationalism or humanism, consent of democracy, social prosperity and faith in God – fired in him an imagination that it might be “a suitable description of the five principles of international behaviour” to which India can subscribe. According to him, these words having been derived from Sanskrit, were easily received in India. He preferred the spelling Panchsheel, as the expression has been in use from the ancient times to describe the five moral precepts of Buddhism relating to personal behaviour, which were “enshrined in the rock edicts of Emperor Ashoka and echoed more than two thousand years later in (Mahatma) Gandhi’s teachings.”

Significance of Panchsheel

The formulation of Panchsheel was a great contribution to International Law. Not only it conforms to the obligations and aims of the United Nations Charter, it has over the years been enlarged by bilateral statements and agreements by many countries. None of the five principles were new to the law of nations, each principle existed as an independent and recognized part of International Law. The great significance of the concept lies in the fact that it has collected all the principles in “a single rubric and in this embodiment has become established as the foundation of contemporary International Law.” While speaking before the Lok Sabha, Nehru had stated that there was nothing new about this concept except that the old idea had gained a new application to a “particular context”, in which it had begun to acquire a specific meaning and significance in world affairs.

To this, Karanjia adds that, Panchsheel was not “the most historical legacy from the past but also. . . a most useful historical imperative in the context of contemporary problems.” Each of the five principles of Panchsheel can be found in the UN Charter. The first principle, namely mutual respect for each other’s territorial integrity and sovereignty , is similar to Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the Charter which states that, “All members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state. …” The second principle, mutual non-aggression, can be found identical to Article 2, Para 3 of the Charter, that international disputes shall be settled by peaceful means in such a manner that “international peace and security and justice are not endangered.” The third principle, mutual non-interference in each other’s internal affairs, resembles Article 2(7) of the Charter, which carries a provision on non-intervention “in matters which are essentially within the domestic jurisdiction of any State. . . .” The fourth principle about equality and mutual benefit resembles Paras 1 and 2 of Article 2 of the UN Charter, where it is provided that the United Nations is “based on the principle of sovereign equality of all its members”, and that “all members, in order to ensure to all of them the rights and benefits resulting from membership shall fulfil in good faith the obligations assumed by them. . . .” Lastly, the fifth principle, dealing with peaceful co-existence, has similar expression in the preamble to the Charter in the following words: “To practice tolerance and live together in peace with one another as good neighbours. …” Thus, the five principles of Panchsheel and the UN Charter can well be compared to reveal identical ideas.

It was a novelty of India’s contribution that these principles were made the foundations of practical state policy and conduct in international relations. If these principles are of ancient lineage in Buddhist literature and have similarity with the purposes and principles of the United Nations Charter, a need for reaffirming those principles in Panchsheel cannot be questioned. Rajan argues that when similar principles were incorporated in the UN Charter, most of the Asian countries were not members of the United Nations. A subscription to Panchsheel by those countries “both reinforced the United Nations and provided those states the basic norms of international behaviour.”

It can be said without any exaggeration that India has played a significant role in that regard. While the American leaders were persuading the countries to join western systems of collective defence in the name of peace, Nehru asked them to join “the alternative method of winning peace by mounting the Panchsheel bandwagon.” He saw in the five principles a challenge to the World. The principles were designed to be a proper structure for building a new international order and to be instrumental in maintaining international peace and security. In fact, Panchsheel can be seen as “a fairly good example of a normative balance of power policy.” Nehru’s major contribution of lasting value to India and its international relations has been the formulation of this doctrine as an alternative political ideal.

Various ideologies were struggling for support in the Afro-Asian region, but Nehru was able to select from the various positions the idea of promotion of peace which he thought was the most suitable. He had proceeded on this approach on the assumption that peace could not be promoted by creating positions of strength- for they were a threat to peace, and there was more possibility of war as a result of military alliances. Nehru knew quite well that a peaceful approach was not a guarantee for peace, but he insisted that it be tried as there was no alternative. Late Judge Nagendra Singh mentioned that the significance of the concept can also be assessed from the fact that it has taken deep roots in the hands of the UN General Assembly.

During the twenty-fifth anniversary of the United Nations in 1970, the General Assembly adopted without vote, a significant Resolution 2625 (XXV), entitled “Declaration on Principles of International Law concerning Friendly Relations and Cooperation among States in Accordance with the Charter of the United Nations.” Having embodied the formulation of the seven principles of International Law referred to in operative Paragraph 1 of General Assembly Resolution 1815 (XVII), the Friendly Relations Declaration bears important evidence to show how the principles underlying Panchsheel have found expression of close resemblance after intensive efforts of the international organization with regard to the promotion of peace in the world community,

Criticism of Panchsheel

Criticisms have been made against Panchsheel right from its inception.

First, Friedmann has argued that there was nothing more than a verbal identity between the doctrine and Panch Shila of Buddhism. The argument is advanced on the ground that Lord Buddha had given the Ten Precepts or Laws of Priesthood, where the first five precepts – abstinence from destroying life, from theft, from fornication and all uncleanliness, from lying, and from liquor, spirits and strong drinks which were a hindrance to merit – had formed a central theme of the Buddhist moral code. This code of morality was meant for personal conduct and it was wrong to state that Panchsheel has been derived from Buddhist literature.

Second, Bozeman commented that a reference to Buddhist morality in the context of Indian external policy was spurious. Buddhist ethics, as originally constituted, was not meant for political ideologies, rather was designed for the “development of non-political morality”, as a result of which, an attempt by Emperor Ashoka to translate Buddhist morality in international relations had proved to be a dismal failure.

Third , Panchsheel was criticised on the ground that the Five Principles had put a seal of approval upon the destruction of Tibet, an ancient country, which was spiritually and culturally associated with India. Tibet had a distinct culture, language and geography and had been independent since 1911 when the Chinese revolution had ended the Manchu Dynasty. Later, the Tibetan Government broke off diplomatic relations with China in 1949 and did not maintain foreign relations with that government since then. Thus, according to the critics, Panchsheel was born out of the surrender in Tibet, and the debacle of Tibet was a debacle of the Five Principles. Tibet wanted to live its own life. Non-intervention, the very fundamental principle of Panchsheel , was broken, as Tibet was not allowed to live its own life and Nehru endorsed the Chinese claim that Tibet was an integral part of China.

Fourth, the Chinese attack on Indian territory and the Soviet invasion of Hungary made “mockery of the high-sounding phrases.” It was stated that Panchsheel , as a code of international morality, was not effective in new situations. A violation of the Five Principles by China, a principal subscriber, proved that there was no respect for the concept. And the critics argued that the concept of Panchsheel had met with a serious setback in the context of Sino-Indian relations. Fifth, there was always a danger, it was added, that principles of coexistence may lead to status quo in international relations, where Imperialism, Colonialism, exploitation and inequality could be allowed to co-exist.

Though Nehru was compelled to admit that people’s faith in Panchsheel or the Bandung spirit had suffered considerably, despite all the criticisms, he defended the principles and expressed that he would not think of a change in the Five Principles of Peace. Panchsheel was the only alternate way to peace. If China had not remained faithful to the concept, “India must adhere to”, said Nehru, “what she had always preached and remained steadfast in the faith.” To Nehru, it was not a matter of faith on one party, it was rather a question of creating an environment, a condition, in which the other party could not break its words. He regarded Panchsheel a “practical idealism.”

Whenever any principle takes birth or is strengthened in international relations, there is always a possibility that the parties subscribing to it may depart from it because of weaker sanction in International Law. Nehru was aware of such a possibility and wrote that there was never anything certain in international relations. A friend may turn enemy tomorrow, but India should not go the way of enmity and suspicion nor should it give a chance to other approaches. Though one should be prepared for any eventuality, it was always better, according to him, to have an honest and sincere faith for the best.

Conclusions

Knowing Nehru from his numerous speeches and writings, and having followed his efforts towards the maintenance of peace, good neighbourliness and moral conduct in international relations, it can be concluded that he could very successfully give not only shape to the constitutional vision of international order for which India has stood, he contributed as well a concept, a doctrine, which has strengthened the regime of the principles of International Law. Though his contribution has been largely at the level of fundamental principles, it can be seen as a development of International Law in Asia. The greatest contribution of Nehru was the doctrine of Panchsheel. The Five Principles were not merely desirable in themselves, they were also unavoidable. It is difficult to ignore completely the idea and its importance; we cannot underestimate it.

Given the polarization of the world into two power blocs on ideological basis, given the fact that an abstract formulation of the doctrine would not be liked by the militarily powerful countries of the West, particularly during the Cold War situation, and given the conflicting interest of many states, the fact that it was accepted by the newly independent states of Asia and Africa, is indeed a great achievement of Nehru. It did set, in fact, certain standards of inter- national conduct. The perspective of Panchsheel determines it is the extent to which the doctrine be studied. It tends to concentrate much on the normative aspects of international peace.

Those who see the concept as one which had gone wrong in international relations, it appears to them sadly incomplete and lacking in balance. To some critics, the ambiguities or inconsistences in the wordings of the doctrine may appear attributable to the fact that its text was not well drafted nor carefully thought of. However, there should be little doubt that Nehru made strenuous efforts, through the idea of the Five Principles, to find the best possible common ground on which the Asian countries and the rest of the world could live in peace with each other. No doubt, the common ground is limited and it conceals many pitfalls, but it cannot be denied that some progress has taken place in strengthening and developing International Law in Asia. There is always a possibility that some subscriber to such principles would never hesitate in violating them for short-term political objectives. A sacrifice of these moral conducts may profit one and hurt others, but the message of Panchsheel will never go in vain; it is bound to work, it will work.