The recently concluded G20 summit in Delhi has put the spotlight on this grouping. Apart from tracing the historical antecedents that led to the formation of G20 and its subsequent evolution, this paper examines its structural dimensions that shape the agenda, decision making process and quality of outcomes. The paper also highlights the geopolitical considerations, including relations between and among states that determine member inclusion and quality of participation. In the course of this discussion, the paper also sheds light on India’s Presidency and the effectiveness of G-20 as a forum so far, and in future.

Historical antecedents

Well before the G-20, the origins of the G7

As the world reeled from the first oil shock in 1973 and the subsequent financial crisis, the heads of state and government of the six leading industrial countries – France, West Germany, the USA, Japan, the United Kingdom and Italy – met in 1975 to discuss the global economy. This meeting was the initiative of French President Valéry Giscard d’Estaing and Chancellor Helmut Schmidt. The first summit meeting was held at the Chateau de Rambouillet, 50 kilometres south-west of Paris.

At this first G6 summit, the leaders adopted a 15-point communiqué, the Declaration of Rambouillet, and agreed to meet in future once a year, under a rotating Presidency. In 1976 Canada joined the group, which henceforth became known as the G7. Very next year, in 1977, the President of the European Commission was invited to attend the G7 summit. Today the President of the European Council also attends the summit meetings.

Then, in the 1980s the G7 extended its interests to embrace foreign and security policy issues. International challenges at that time included the long-standing conflict between Iran and Iraq and the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. But on 18th May 1988, the Soviets began their final withdrawal from Afghanistan. Soon thereafter, Soviet Russia was formally admitted to the group, making it the G8.

Ironically this got reversed 25 years later due to another military action by Russia. In February-March 2014, Russia invaded the Crimean Peninsula, part of Ukraine, and then annexed it. The United States and the European Union responded by enacting sanctions against Russia for its role in the crisis, and urged Russia to withdraw. Further, as a result of Russia’s violation of the sovereignty and territorial integrity of Ukraine with the annexation of Crimea, the heads of state and government of the G7 decided not to attend the planned G8 summit in Sochi under the Russian Presidency. So, rather than meeting in Sochi, the other member states met on 4 and 5 June 2014 in Brussels, again as G-7.[1] But let us go back to how the G-7 incubated the G-20.

G7 and the global financial crises of 1998-1999

A series of substantial debt crises swept through emerging markets in the late 1990s. These crises included the Mexican peso crisis and extending to the 1997 Asian financial crisis, the 1998 Russian financial crisis, and the notable collapse of the hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management in the autumn of 1998. A forum was needed to discuss the response to these crises. Apart from the World Bank and the IMF, there were no other bodies at the international level where the developed and developing countries could come together and exchange ideas on global financial and economic issues. The World Bank and the IMF annual meetings were large and unwieldy where finance ministers delivered written speeches. The need for a more compact deliberative body was sorely felt.

Paul Martin who is often times described as “the crucial architect of the formation of the G20” and his American counterpart the then Treasury Secretary Larry Summers, realized that the existing structures like the G7, G8, and the World Bank and the IMF were inadequate for ensuring financial stability in an increasingly globalized world. In recognition of this limitation, they conceptualized a new, more inclusive and permanent group consisting of major world economies. This envisioned group aimed to provide both a voice to emerging economies and share with them the responsibilities for addressing global financial stability challenges.[2] The initiative to form such a group was taken by the G7 during the 1999 autumn meeting of the IMF and the World Bank in Washington.

From G7 to G20 – India among the first to join G20 in 1999

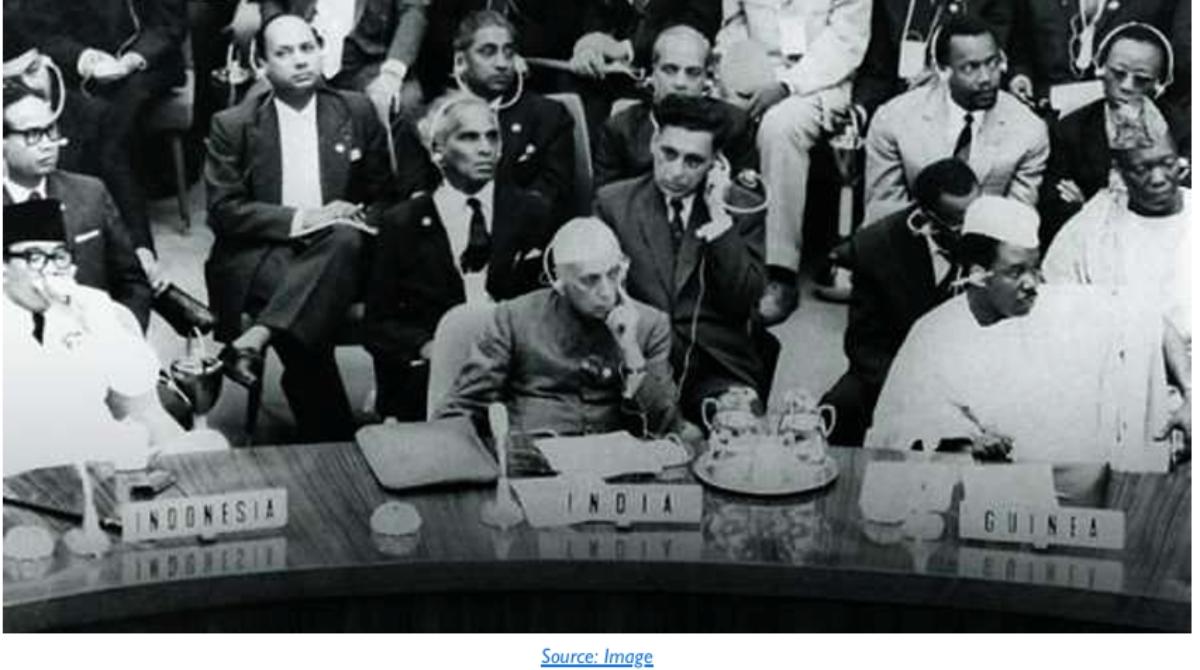

When the G-20 was being conceived, India was one of the first developing countries to be asked to join. Yashwant Sinha, then Finance Minister of India recalls the events:

“Paul Martin, the finance minister of Canada acting on behalf of the G7, invited me to a meeting in which he mentioned the idea that had already been discussed in the G7 to constitute a bigger and more representative group of finance ministers and central bank governors consisting of the G8 and some important emerging market countries to deliberate in depth upon the developing financial and economic global situation. He told me that India was naturally the first country in the group of emerging market countries he felt he should talk to.

“Will India agree to become a member of the group?” he asked me. I replied in the affirmative and then we went on to discuss the names of the other countries to be included in the group and its mandate. Discussions with the others followed and the G20 came into existence in September 1999. Martin became its first chairman and the first meeting of the group was held in Berlin in the renovated Bundestag building in December 1999. I was elected the second chairman of the group a little later. My chairmanship of the G20 was a small piece of news in the financial papers in India as was my chairmanship of the development committee of the World Bank. In the Vajpayee government, we believed in doing our work quietly without much fanfare.”[3]

Although the next meeting was scheduled to be held in Delhi in the autumn of 2001, it was shifted to New York to show the world’s solidarity with the US following the terrorist 9/11 attack. The G20 finance ministers and central bank governors finally met in New Delhi in autumn 2002 under the chairmanship of Jaswant Singh, who had by then succeeded Yashwant Sinha as finance minister.

Evolution Since 2009

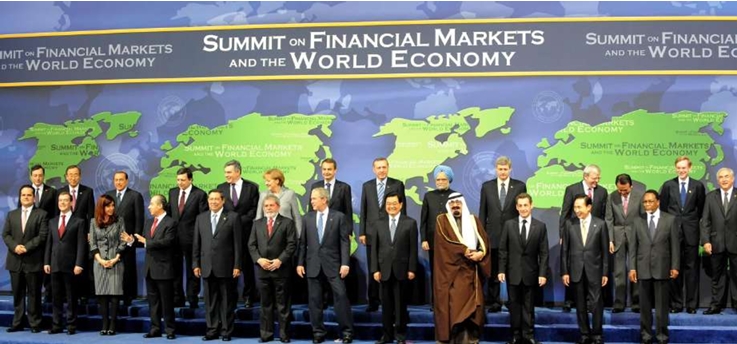

Recognizing the inclusion of diverse political systems, former CFR fellow Stewart Patrick highlighted the G20’s 2008 elevation as a pivotal moment in global governance. He argued that this group is the most appropriate platform for addressing the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic.[4]

The G20 was widely credited for its swift response during the 2008 financial crisis, with experts acknowledging its pivotal role in rescuing a faltering global financial system. In 2008 and 2009, G20 nations collaborated on a $4 trillion spending initiative to stimulate their economies, rejected trade barriers, and implemented extensive financial system reforms.[5]

During its 2009 summit, the G20 proclaimed itself as the central forum for international economic and financial collaboration.[6] Over the following decade, the group has gained increased prominence and is acknowledged by analysts for wielding significant global influence.

Different Presidencies of the G-20 and expanding its scope

An important issue is which member nation gets to chair the G20 leaders’ meeting for a given year. All countries within a group are eligible to take over the G20 Presidency when it is their group’s turn. Therefore, the states within the relevant group need to negotiate among themselves to select the next G20 President. Each year, a different G20 member country assumes the presidency starting from 1 December until 30 November. This system has been in place since 2010, when South Korea, which is in Group 5, held the G20 chair. [7]

An important decision taken was to divide the member countries into five groups to make it easier to select an annual chairman. Group one consists of Australia, Canada, Saudi Arabia and the US; group two of India, Russia, South Africa and Turkey; group three of Argentina, Brazil and Mexico; group four of France, Germany, Italy and the UK and group five of China, Indonesia, Japan and South Korea. The countries within the group decide which from amongst them will take over as chairman when it is the group’s turn.

It is the presidency’s prerogative to define a set of priorities, in consultation with other members, for the year ahead and that country is responsible for hosting and organizing the annual Leaders’ Summit. Leaders traditionally release a final statement or communiqué summarizing agreed initiatives and policy advancements.

In June 2010, Singapore’s representative at the United Nations cautioned the G20 that its decisions would impact nations of all sizes. Emphasizing the need for inclusive financial reform discussions, Singapore played a pivotal role in establishing the Global Governance Group (3G), an informal coalition of 30 non-G20 countries, which included microstates and several Third World nations. The purpose was to collectively articulate their perspectives within the G20 framework more effectively. Singapore’s leadership of the 3G [8] was acknowledged as a justification for its invitation to the G20 summits and its related processes from 2010 to 2011 and from 2013 to 2023.[9]

A 2011 report released by the Asian Development Bank (ADB) argued that large Asian economies such as China and India would play a more important role in global economic governance in the future. The report claimed that the rise of emerging market economies heralded a new world order, in which the G20 would become the global economic steering committee. The ADB furthermore noted that Asian countries had led the global recovery following the late-2000s recession. It predicted that the region would have a greater presence on the global stage, shaping the G20’s agenda for balanced and sustainable growth through strengthening intraregional trade and stimulating domestic demand.[10]

On 1 December 2016, Germany became the host and President of the G20 and began to work within the so-called G20 Troika, which in addition to itself consists of the previous 2016 G20 President (China) and the subsequent 2018 President (Argentina). [11]

Today the G20, composed of the finance ministries of the world’s major economies, encompasses both developed and developing nations, and represents approximately 80% of the global gross world product (GWP), 75% of international trade, two-thirds of the world’s population, and 60% of the Earth’s land area.[12]

Economic and financial coordination remains the centrepiece of each summit’s agenda, but issues such as the future of work, climate change, and global health are recurring focuses as well. Broader agendas became more common in the decade following the global financial crisis, when the G20 was able to turn its attention beyond acute economic crisis management. However, at recent summits, countries have struggled to reach a unified consensus—the hallmark of previous iterations of the conference—as the interests of high- and low-income economies continue to diverge.

Issues addressed beyond the economy

The COVID-19 pandemic posed a major test for the group, which Patrick has criticized for largely failing to move beyond “uncoordinated national policies.”[13] However, G20 countries did agree to suspend debt payments owed to them by some of the world’s poorest countries, providing billions of dollars in relief.

Although climate change has been a focus of recent summits, meetings have yielded few concrete commitments on the issue. At the 2021 Rome summit, countries agreed to curb emissions of methane and end public financing for most new coal power plants overseas, but they said nothing about limiting coal use domestically. (China, the world’s largest emitter, permitted more domestic coal power plants in 2022 than any year since 2015). At the 2022 gathering, Indonesia agreed to close coal power plants in exchange for $20 billion in financing from high-income countries, including the United States. But as of 2023, it is still building coal-fired plants.[14]

The following year, Indonesia held the G20 presidency from 1 December 2021 to 30 November 2022. During its presidency, Indonesia focused on the global COVID-19 pandemic and how to collectively overcome the challenges related to it. The three priorities of Indonesia’s G20 presidency were global health architecture, digital transformations, and sustainable energy transitions.[15]

Structure as a facilitator and inhibitor

Policy and international relations experts argue that the G20’s composition is superior to that of G7. The G20 including emerging democracies like Brazil, India, and Indonesia, along with influential autocratic nations such as China, Russia, and Saudi Arabia, better reflects the current distribution of international power compared to earlier groups like the G7.[16] (Russia’s G7 membership was indefinitely suspended in 2014 due to its annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region).

Interestingly, the expansion of G7 into G20 has not extinguished the existence of G7. While G7 members are members of G20 as well, G7 has retained its separate identity. In a sense the relationship of G7 with G20 is similar to that of Security Council with General Assembly of the United Nations; but without the element of veto power. The G7 with smaller number of members with similar economic and political configurations was a much tighter and cohesive grouping. In contrast, the G20 is diverse and less compact, if not unwieldy .

In addition to these 21 members, the chief executive officers of several other international forums and institutions participate in meetings of the G20. These include the managing director and Chairman of the International Monetary Fund, the President of the World Bank, the International Monetary and Financial Committee and the Chairman of the Development Assistance Committee.

An issue that has occasionally surfaced relates to the establishment of a permanent secretariat. It has been argued that the G20 has been using the OECD as a secretariat. In 2010, President of France Nicolas Sarkozy proposed the establishment of a permanent G20 secretariat, similar to the United Nations. Seoul and Paris were suggested as possible locations for its headquarters. Brazil and China supported the establishment of a secretariat, while Italy and Japan expressed opposition to the proposal. South Korea proposed a “cyber secretariat” as an alternative.

Like the G7, the G20 is not based on a treaty and has no permanent secretariat. In 2008, in the wake of another global financial crisis, it was decided to raise the G20 to the summit level. Two tracks were created: One of the finance ministers and the central bank governors and the other of Sherpa to tackle other issues like climate change.

Who gets to join, and who cannot

Although the G20 has stated that the group’s “economic weight and broad membership gives it a high degree of legitimacy and influence over the management of the global economy and financial system”, its legitimacy has been challenged. [17] A 2011 report for the Danish Institute for International Studies criticised the G20’s exclusivity, particularly highlighting its under-representation of African countries and its practice of inviting observers from non-member states as a mere “concession at the margins”, which does not grant the organisation representational legitimacy.

Concerning the membership issue, US President Barack Obama noted the difficulty of pleasing everyone: “Everybody wants the smallest possible group that includes them. So, if they’re the 21st largest nation in the world, they want the G-21, and think it’s highly unfair if they have been cut out.” Others stated in 2011 that the exclusivity is not an insurmountable problem and proposed mechanisms by which it could become more inclusive.[18]

Moreover, Norwegian Prime Minister, Støre believes that the G20, a group of influential countries making global decisions, “isn’t fair because it leaves out many important nations, including Norway” He has stated that decisions affecting the whole world should involve everyone, not just a select few. This exclusion, according to him, undermines the importance of international organizations formed after World War II, and he advocates for a more inclusive approach in global decision-making.

In addition, before the 2009 G20 London summit, the Polish government expressed an interest in joining with Spain and the Netherlands and condemned an “organisational mess” in which a few European leaders spoke in the name of the collective EU without legitimate authorisation in cases which belong to the European Commission. During a 2010 meeting with foreign diplomats, Polish president Lech Kaczyński said:

“The Polish economy is according to our data the 18th world economy. The place of my country is among the members of the G20. This is a very simple postulate: firstly – it results from the size of the Polish economy, secondly – it results from the fact that Poland is the biggest country in its region and the biggest country that has experienced a certain story. That story is a political and economic transformation.” [19]

Poland’s GDP in 2021 (over $655 billion according to IMF estimates) was significantly larger than those of South Africa ($415 billion) and Argentina ($455 billion), which have the smallest economies among G20 countries. Poland has been campaigning to replace Russia in G20[20] .

During a visit to Washington in March 2022, Poland’s development minister, Piotr Nowak, told US Trade Representative Katherine Tai that there should be “no place for Russia in the G20” after it “violated the rules of international cooperation by attacking Ukraine”. Nowak further argued that Poland’s admission to the group would be a mark of success for Western institutions, showing how they had effectively supported Poland’s post-communist transition over the last three decades[21].

Independent of the Polish minister’s plea, that very month U.S. President Joe Biden called for the removal of Russia from the group. Alternatively, he suggested that Ukraine be allowed to attend the G20 2022 summit, despite its lack of membership.[22] Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau also said the group should “re-evaluate” Russia’s participation.[23]

Russia claims it would not be a significant issue, as most G20 members are already fighting Russia economically due to the war.[24] China suggested that expelling Russia would be counterproductive.[25] In November 2022, Indonesia and Russia stated that Vladimir Putin would not attend the G20 summit in person, but may attend virtually[26].

Interestingly, during the 2022 summit, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy delivered a video statement where he repeatedly referred to the assembly as the ‘G19,’ expressing his stance on the exclusion of Russia from the group.

That the Global South must be paid greater heed to is an obvious fact, one to which the upholders of the order established after the Second World War have remained deaf for too long. However, the worst thing would be for the countries that make it up to emerge as new agents of inertia, at a time when the world is threatened with fragmentation.[27]

So, when New Delhi presided over the admittance of the African Union (AU) – also the first inclusion since 1999 – expanding representation to fifty-five countries, this allowed Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi to “showcase his status as the leader of a rising India,” according to CFR’s Manjari Chatterjee Miller and Clare Harris.

India’s Presidency

India took over the Presidency from Indonesia. As the 2023 host, India sought to cast itself as a voice for the so-called Global South, framing the agenda around issues facing lower-income countries. These included rising debt levels, persistently high inflation, depreciating local currencies, food insecurity, and increasing severe weather events associated with climate change.

The fanfare and razzmatazz surrounding India’s 2023 G20 presidency was such that most Indians would be forgiven if they thought that this was the first time that the Summit was being held and it was India that was hosting it. The Delhi meet in 2002 was after all so low key and it was in such a distant past.

Summit theme

The New Delhi summit was held on September 9 and 10. The summit was essentially the culmination of all the G20 processes and meetings held throughout the year among ministers, senior officials, and civil societies. The theme of the summit Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam or “वसुधैव कुटुम्बकम्” in Sanskrit or translated as “One Earth, One Family, One Future'” in English.

In an interview on 26 August 2023, Prime Minister Narendra Modi expressed optimism about the G20 countries’ evolving agenda under India’s presidency, shifting toward a human-centric development approach that aligns with the concerns of the Global South, including addressing climate change, debt restructuring through the G20’s Common Framework for debt, and a strategy for regulation of global crypto-currencies.

India’s G20 priorities

India’s G20 priorities encompassed financing sustainable urbanization, leading in the energy transition, and enhancing global health systems. The focus on upgrading city infrastructure and services acknowledged the challenges of rapid urbanization, but critics questioned the feasibility of mobilizing $5.5 trillion annually and stress the importance of addressing existing urban issues. In the realm of energy transition, India’s commitment to renewable/s has been commendable, yet sceptics raised concerns about the ambitious targets and the actual implementation of programs like the National Hydrogen Mission. The call for G20 collaboration on critical minerals and supply chains faced scepticism regarding the practicality of such coordination.[28]

On healthcare, the emphasis on global cooperation post-COVID-19 is vital, but critics argued that more concrete steps were needed for equitable vaccine distribution and healthcare access. Additionally, while the mention of the Digital Health Mission was promising, there were concerns about data privacy and the potential exclusion of marginalized populations.

While the Asian Development Bank’s (ADB) support was acknowledged, critics have questioned the feasibility and impact of initiatives like creating “Investable Cities” and the Climate and Health Hub. Scepticism was also there regarding the effectiveness of ADB’s support in achieving tangible outcomes, particularly in the context of addressing complex challenges like climate change and health crises.

While India’s G20 agenda was ambitious and commendable, a critical lens revealed potential challenges in implementation, financing, and the actual impact on the ground. Addressing these concerns and ensuring transparency and accountability was crucial for the success and lasting legacy of India’s G20 Presidency.

Challenges to Consensus

A rough edge to the summit was the absence of three leaders: Chinese President Xi Jinping, Russian President Vladimir Putin and Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador. No previous G20 summit has had so many absentees among leaders. Of the missing leaders, Xi’s absence was perhaps the most telling – he leads the world’s second-largest economy – and has never skipped a G20 summit in the past.

Commenting on this, Ashok Kantha, former Indian ambassador to Beijing and also former secretary in India’s foreign ministry where he oversaw relations with 65 countries, observed: “This will be seen as a negative signal from China – both in bilateral and global relations. It sends a signal that relations are still in a downward spiral and shows China’s lack of commitment to G20”.

During the 2023 Delhi Summit, any labeling of Russia as a war-monger, along with any explicit condemnation of its actions, was muted. The broad invitation for all nations to respect “territorial integrity and sovereignty” left Moscow unimpressed, considering its historical actions that contradict such principles. Notably, Vladimir Putin’s absence in India prevented a potentially embarrassing image for the G20, avoiding a situation where the Moscow leader would be present at a memorial dedicated to Mahatma Gandhi, an advocate of non-violence and the father of Indian independence.

Despite denouncing the use of force for territorial gain, the G20 statement refrained from directly criticizing Russia by name, stating that there were “different views and assessments of the situation.” This approach drew criticism from Ukraine’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesman Oleg Nikolenko, who remarked that the G20 had “nothing to be proud of.”

Moreover, the deteriorating relationship between India and Canada, marked by Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s explosive accusations of Indian involvement in the assassination of a Sikh leader, cast a shadow over the recent G20 summit held in India. Trudeau’s claims led to a tit-for-tat expulsion of diplomats and a frosty reception for the Canadian leader at the summit, underlining the severity of the tensions.

The suspension of trade talks between the two nations further underscored the economic impact of political differences. The dispute’s global implications were evident as other G20 nations, including the United States, expressed concern and emphasized the need for a thorough investigation. Additionally, Trudeau’s domestic political struggles and the perceived insensitivity to India’s concerns about rising extremism within the Sikh diaspora in Canada pose challenges to Canada’s Indo-Pacific strategy. [29]

The Declaration, a result of intense negotiations among G20 member nations, also lacks a comprehensive reassessment of neoliberal market-driven economies and GDP-centric growth paradigms. It raised concerns over the Declaration’s omission of critical issues such as the erosion of civic space and the global decline in democracy. “This alarming trend is especially pertinent in several G20 countries, including China, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Türkiye, Mexico, and India, as highlighted by CIVICUS’s Civic Space Monitor,” it said.[30]

An assessment of G-20

The obvious advantage of a forum like G20 is that it gets together some of the most powerful leaders of the world. For example, the 2016 summit in China also showed the power of bringing leaders together when President Barack Obama and the Chinese leader, Xi Jinping, announced that their countries would sign on to the Paris Agreement on climate.

More recently, in 2021, the G20 supported a major tax overhaul that included a global minimum tax of at least 15 percent for each country. It also backed new rules that would require large global businesses like Amazon to pay taxes in countries where their products are sold, even if they lack offices there. The plan promised to add billions in government revenue and make tax havens less of a driving force for corporations. But, as with a lot of G20 statements, follow-through has been weak. According to the International Monetary Fund “The global tax agreement is an important step in the right direction, but it is not yet operational.”[31]

Effectiveness

So, what accounts for this lack of effectiveness? There seems to be five major reasons.

The first is the non-binding nature of G20 Declarations, even when unanimous. For example, despite the G20 introducing a unified framework for debt treatment before its 2020 summit, only four countries—Chad, Ethiopia, Ghana, and Zambia—have sought debt relief under this arrangement. Experts attribute this low uptake to divisions among lending countries.[32] “No framework for coordination among official creditors can work if official creditors don’t have enough in common to work together,” CFR senior fellow Brad W. Setser wrote in March 2023. “The ‘Common Framework’ exists in name only.” [33] International lenders are now considering ways to reform the framework. There are numerous such examples about G-20 intentional declarations not getting implemented for years.

Second, economic and strategic compulsions trump intent, with the latter pushed back to near future at best. For example, on the climate-energy nexus, it is noteworthy that the G20 countries account for almost 75% of global carbon emissions. Despite these promises G20 members have subsidised fossil fuel companies over $3.3 trillion between 2015 and 2021, with several states increasing subsidies; Australia (+48.2%), the US (+36.7%), Indonesia (+26.6%), France (+23.8%), China (+4.1%), Brazil (+3.0%), Mexico (+2.6%).China alone generates over half of the coal-generated electricity in the world.[34]

Third is structural-systemic inadequacies. For example, apart from the contentious handling of climate change issues, G20 nations have been grappling with internal disagreements on how to address the economic repercussions that disproportionately affected emerging economies. The conflict-related energy crisis stemming from the war in Ukraine has resulted in shortages of food, surging energy prices, and inflationary pressures. These factors have contributed to a strengthening U.S. dollar, negatively impacting the currencies of emerging economies. Consequently, more nations are seeking financial assistance from international lenders, with over a hundred countries requesting urgent aid from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) since the start of the pandemic. In 2022, IMF lending to struggling economies reached a record high of $140 billion.

Fourth is the very composition of G20. In a recent article in The New York Times[35] (Sept 6, 2023) Why the G20 Keeps Failing, and Still Matters, Damien Cave says that “summits like the one in India have produced many ambitious statements — and, often, disappointing results. Most of the grouping’s joint statements since it formed in 1999 have been dominated by resolutions as solid as gas fumes, with no clear consequences when nations underperform.” This is because the G20 was flawed from the start, with a membership roster based on the whims of Western finance officials and central bankers.

Robert Wade, a political economy professor at the London School of Economics, said “[German and American officials] went down the list of countries saying, Canada in, Portugal out, South Africa in, Nigeria and Egypt out, and so on.”

An apocryphal story lies behind Argentina’s membership of G-20. Argentina is neither an emerging economy nor among the 20 largest. It is a G20 member because one of its former economy ministers, Domingo Cavallo, was a Harvard roommate of Larry Summers, the U.S. Treasury secretary from 1999 to 2001; and the organization still suffered from a “lack of representational procedures,” without a well-defined process for inclusion. “A given state is in or out, permanently”.

Fifth, dissatisfaction with globalization and free trade has made it harder for G20 members to agree on a consensus about how to hold the world together. Conflicts have supplanted G20 team efforts. Nationalism has surged as networked economies have come to look far riskier after the Covid-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine, which has pushed up food and energy prices for countries far from the front lines.

Stewart Patrick, director of the Global Order and Institutions Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace said: “There’s a lot more dissatisfaction with hyper-globalization, open trade and free capital. In a situation where the global economy is fracturing and countries are pursuing their own thing, the question is, what do you do when you still have rules and institutions that were created for a very different environment?”[36]

Finally, the cost and extent of summit-related security is often a contentious issue in the hosting country, and G20 summits have attracted protesters from a variety of backgrounds, including information activists, opponents of fractional-reserve banking and anti-capitalists. In 2010, the Toronto G20 summit sparked mass protests and rioting, leading to the largest mass arrest in Canada’s history.[37]

Looking ahead

Many foreign policy experts argue that the G20’s failures simply point to the need for modernization in international institutions. Dani Rodrik and Stephen M. Walt’s in Foreign Affairs said: “It is increasingly clear that the existing, Western-oriented approach is no longer adequate to address the many forces governing international power relations.” And they see a future with less agreement, in which “Western policy preferences will prevail less and each country will have to be granted greater leeway in managing its economy, society and political system.”[38] Some have called for a reformulated G20, by discussing how to separate the benefits of trade from the risks of overindulging the free-market system that the organization was built to protect. “The G20 would be a natural place to begin hammering out what rules of peaceful coexistence permit countries to share in a more tempered globalization (and) that would be a positive agenda.”[39]

[1] https://www.bundesregierung.de/breg-en/service/the-history-of-the-g7

[2] https://risingkashmir.com/one-earth-one-family-one-future–india-at-the-helm-of-g20-de6ca70b-274f-49c4-95df-79fa7723f1ab

[3] https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/g20-presidency-in-the-vajpayee-era-when-india-did-not-strut-8345539/

[4]ibid

[5] https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/internatio nal-business/g20-countries-account-for-85-of-global-gdp-75-of-world-trade/articleshow/47670497.cms

[6] Officials: G-20 to supplant G-8 as international economic council”. CNN. 25 September 2009. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

[7] The Rotating G20 Presidency: How do member countries take turns?”. boell.de. 30 November 2016. Retrieved 3 March, 2019

[8] “Press Statement by the Global Governance Group (3G) on its Ninth Ministerial Meeting in New York on 22 September 2016”. mfa. 22 September 2016. Retrieved 23 July, 2017.

[9] “Singapore among five non-G20 nations to attend Seoul Summit” Archived 22 July 2012 at archive today. International Business Times. 25 September 2010. Retrieved 12 February 2013.

[10] https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/28608/asia2050-executive-summary.pdf

[11]https://www.boell.de/en/2016/11/30/rotating-g20-presidency-how-do-member-countries-take-turns

[12] https://www.oecd.org/g20/about/

[13] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/what-is-the-g20-whos-in-it-and-what-happens-at-its-summits

[14] https://www.reuters.com/business/environment/g20-leaders-try-cap-global-warming-15-degrees-draft-2021-10-30/

[15] https://www.icwa.in/show_content.php?lang=1&level=3&ls_id=9051&lid=5884

[16]https://www.reuters.com/world/what-is-g20-what-are-key-issues-2023-summit-2023-09-04/

[17] https://www.cgdev.org/article/overhaul-g-20-sake-g-172-financial-times

[18] https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/epdf/10.1080/13600826.2020.1739630?needAccess=true

[19] Kamila Wronowska (2 March 2010). “Polska w G-20 – warto się bić?” [Poland in the G-20 – is it worth the fight?]. dziennik.pl (in Polish).

[20] https://notesfrompoland.com/2022/03/23/poland-campaigns-to-replace-russia-in-g20/

[21] Ibid.

[22] Canberra considers barring Vladimir Putin from G20 in Brisbane over Crimea crisis”. The Australian. 20 March 2014. Retrieved 7 October 2015.

[23]Boisvert, Nick (31 March 2022). “Trudeau calls on G20 to reconsider Russia’s seat at the table”. CBC News. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

[24] Pettypiece, Shannon (24 March 2022). “Biden says allies must stay united against Russia, expel it from the G-20”. NBC News. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

[25]Sommerlad, Joe (25 March 2022). “What is the G20 and could Russia be expelled?”. The Independent. Retrieved 25 March 2022.

[26]Teresia, Ananda (10 November 2022). “Russia’s Putin will not attend G20 summit in Bali in person”. Reuters. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

[27]https://www.lemonde.fr/en/opinion/article/2023/09/11/the-g20-in-new-delhi-a-summit-without-major-results_6132551_23.html

[28] https://www.adb.org/news/features/indias-g20-presidency-opportunity

[29] https://www.orfonline.org/research/trudeau-has-lost-the-plot-on-india/

[30]https://thewire.in/rights/civil-society-calls-out-g20-declarations-omission-of-civic-space-erosion-democracy-decline

[31] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/06/world/asia/g20-summit-india.html

[32]https://www.cfr.org/backgrounder/what-does-g20-do

[33]Ibid.

[34]Ibid.

[35] https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/06/world/asia/g20-summit-india.html#:~:text=Many%20foreign%20policy%20experts%20argue,for%20modernization%20in%20international%20institutions.

[36] Ibid

[37]https://www.g20.org/en/workstreams/engagement-groups/

[38] Cave, op. cit.

[39] ibid