Introduction

Beginning with the May 2024 issue of Policy Watch, we had embarked on a three-part series on India’s Relations with Neighbours. While the May 24 issue took a geostrategic perspective delineating India’s relations with China, the November 24 issue covered four other neighbours: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Maldives and Bangladesh. The next issue in December 24 covered the remaining four neighbours, viz. Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Bhutan and Nepal.

Overall, we had identified four critical aspects that determined our relationship with neighbours. While not all the factors were evident across the board, the pattern was still unmistakable.

First, the various political parties’ route to capture and retain power often came in the way of building sound bilateral relations, and the negative impacts could be severe. Developments in India, Pakistan, Nepal, Maldives and Bangladesh were ample proof.

Second, the domestic power-play needed great skill and statecraft to shed the negative baggage of above and build bilateral relations. Muizzu and Dissanayake were two different but apt practitioners of this art, while Oli of Nepal and Yunus of Bangladesh were not.

Third, the anger and sense of alienation that citizens of the country on the receiving end feel may undo the leaders’ words and actions. We had said that it would take Maldives a long time to see the earlier level of tourist influx from India, or for the wounds of Bangladeshis to heal for being called termites.

Fourth, China casts its long shadow on our relations with neighbours. China has demonstrated to the world that India must pay a price for China to be seen as the emerging superpower. Our smaller neighbours now have a choice. Gone are the days when India could play the big brother role; now it will be seen more as intervention. And almost as a corollary, smaller neighbours may be inclined to play China-India card to gain concessions.

In this paper, we are primarily focussing on recent developments that have significantly shifted the narrative in our relations with our neighbours. Our primary focus is on Bangladesh and Pakistan, with secondary references to Myanmar, China and Afghanistan.

India’s responses to developments in and with Bangladesh and Pakistan have been very different, but together, display a reset in India’s framework in dealing with neighbours. To what extent these can (or should) be sustained in the long run, it is too early to say; but a broader critique can be made.

The constraints posed by Myanmar and China are expectedly on different planes. As against this, the way we are engaging with the current Taliban administration in Afghanistan or the junta in Myanmar presents a different story and offers alternative possibilities in engaging with neighbours and building relations with them.

Bangladesh

After what may be called a roller-coaster ride during Sheikh Hasina’s fifteen-year reign, India-Bangladesh relations have suddenly entered a turbulent phase. Her furtive flight to India on 5 August 2024 was a watershed moment, both for her as well as for Bangladesh. Her political reign was increasingly viewed as authoritarian, backsliding of democracy with a clampdown on dissent, and a questionable election. India was seen to have propped her up. So, it was inevitable that the collapse of Hasina’s reign and seeking refuge in India would also have significant impact on India.

Hasina apart, given the volatile socio-political fabric of Bangladesh, the rabid othering of Bangladeshi (Muslims) in India – most tellingly described as termites, the love-hate relationship embedded in a “once liberator, now a meddlesome big brother”, the rapid deterioration in India’s ties with Bangladesh should have taken no one by surprise. Yet, the causal relationship does raise an inverse question: if the influencing factors had been moderated, if not altogether jettisoned, would outcomes have been different for India? In the following sub-sections, we have attempted to examine this aspect.

On 5 August 2024, Sheikh Hasina, Prime Minister of Bangladesh fled to India because her regime had collapsed after being in power for three consecutive terms. What ostensibly started as a student protest when they took to the streets demanding the scrapping of quotas for government jobs – culminating in 67 deaths on July 19, 2024 – soon spiralled out of control. Hasina calling the student protesters Razakars – those who sided with the West Pakistan army during Bangladesh’s liberation struggle – only fuelled angst against her.

On 5 August 2024, Sheikh Hasina, Prime Minister of Bangladesh fled to India because her regime had collapsed after being in power for three consecutive terms. What ostensibly started as a student protest when they took to the streets demanding the scrapping of quotas for government jobs – culminating in 67 deaths on July 19, 2024 – soon spiralled out of control. Hasina calling the student protesters Razakars – those who sided with the West Pakistan army during Bangladesh’s liberation struggle – only fuelled angst against her.6

In a national address, Bangladesh’s army chief, Gen. Waker-uz-Zaman confirmed Hasina had resigned and said the military would form an interim government. Addressing protesters, largely young Bangladeshis and students, he said: “Whatever demands you have we will fulfil and bring back peace to the nation, please help us in this, stay away from violence.” And “the military will not fire at anyone, the police will not fire at anyone, I have given orders,” he added.

Scenes of jubilation erupted on the streets as protesters celebrated the end of her 15 years in power by climbing on tanks and scaling a statue of Hasina’s father and independence leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in Dhaka, attacking the head with an axe.7

With Hasina at the helm, India had very cordial relations with Bangladesh – reflected in trade, commerce, infrastructure development, but specially in security matters. But all that changed swiftly as the interim government headed by Chief Adviser, Muhammad Yunus took charge. In the following sub-sections, we highlight some of the issues that have strained relations between the two countries.

The first substantive sign came in early November 2024, when Bangladesh, the world’s second-largest garment producer, opted to bypass India and ship its textiles to global markets through the Maldives, hurting the cargo revenue prospects of India’s airports and ports amid strained bilateral ties. Bangladesh was rerouting its textile exports to the Maldives by sea and then dispatching cargoes by air to its global customers, including H&M and Zara.

Quoting from Indian newspapers The Morning Star of Bangladesh said, “This shift means India’s airports and ports lose revenue previously earned from handling these cargoes”. The redirection of textile exports could weaken trade relations between India and Bangladesh and reduce the collaborative opportunities in logistics and infrastructure projects.8

But others added a different perspective. People associated with the industry dismissed suggestions that the move was linked to the ouster in August of former Bangladesh prime minister Sheikh Hasina, who was currently said to be staying in India.

According to Anil Buchasia, executive member, eastern region, Apparel Export Promotion Council, “There’s nothing to read into this. Indian airports are already congested, and we had also requested the government to restrict Bangladeshi textiles from passing through Indian airports.”

Besides, industry experts suggested that Bangladesh took this step to gain greater control over its supply chain and meet its shipment deadlines by avoiding delays caused at India’s airports. “This new route offers Bangladesh a strategic advantage along with improved reliability, which is crucial for meeting tight deadlines in the international clothing market,” said Arun Kumar, president of the Association of Multimodal Transport Operators of India.9

Kumar explained that textiles were also treated as perishable goods and that failure to deliver them on time results in the rejection of consignments. Garments meant for a specific season lose their value if they are delivered late.

On 2 December 2024, the Office of the Assistant High Commission of Bangladesh in Agartala was vandalised by Hindu Sangharsh Samity, a right-wing organisation, who were protesting the oppression of minorities in Bangladesh, calling for the release of ISKCON member Chinmoy Krishna Das and cessation of religious persecution.10

Bangladesh’s response – both public and official – was swift. Anti-India protests broke out. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Bangladesh not only said it “deeply resents the violent demonstration and attack” on its mission at Agartala, but it also castigated India. “Accounts received conclusively attest that the protesters were allowed to aggress into the premises,” the MFA statement said, stressing that the attack was carried out in a “pre-planned manner.”

The spat continued. While Bangladesh’s interim government summoned the Indian high commissioner in Dhaka, in India, politicians of India’s ruling Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) threatened to impose an “indefinite export embargo If the attacks on Hindus and their religious establishments do not stop by next week”.

BJP’s Suvendu Adhikari, leader of the opposition in the West Bengal assembly, said. “After the beginning of next year, we will stop trade for an indefinite period. We will see how the people there live without our potatoes and onions,” he warned.

A more nuanced picture is provided by Dr. Sudha Ramachandran, independent researcher and journalist. Writing for The Diplomat,11she says, days before the incident at Agartala, India and Bangladesh were locked in a war of words following the arrest of Bangladeshi Hindu monk Chinmoy Krishna Das in Chittagong on charges of sedition for allegedly disrespecting the Bangladeshi national flag. His arrest set off clashes and tensions in Bangladesh, and protests in several Indian cities by activists from Hindu organizations and the BJP.

Following his arrest, India’s Ministry of External Affairs called on Bangladesh’s interim government “to take all steps for the protection of minorities.” “We are concerned at the surge of extremist rhetoric, increasing incidents of violence and provocation [in Bangladesh],” MEA spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal said at a news conference.

Awami League was in power in Bangladesh. Hasina was perceived as a “trusted friend and ally” of India, especially since she was seen to be “sensitive to India’s security concerns.” However, with her exit from power, Delhi-Dhaka ties have come under strain.

Ramachandran quotes a Dhaka University professor: “As far as Bangladesh is concerned, Hasina’s continued presence in India is the main irritant in bilateral relations”. Although the Muhammad Yunus-led interim government has called for her extradition to face trial in Bangladesh for alleged war crimes, India has not heeded the request.

For India, the resurgence of Islamist forces in post-Hasina Bangladesh is an important concern. Ramachandran also quotes Smruti S. Pattanaik, a research fellow at the New Delhi-based Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, who was in Bangladesh recently: “While the politics of Islamism has always been a part of Bangladesh’s political journey, the Jamaat-e-Islami [JI] appears to be more dominant now. In terms of political discourse, Islamism appears to be dominant in defining post-Hasina politics.”

The JI, which is Bangladesh’s largest Islamist party, collaborated with Pakistan during the 1971 liberation war and is perceived in New Delhi to be pro-Pakistan. While it was put on a tight leash during Hasina’s rule — several JI leaders were convicted, even executed for war crimes, and the party was banned and hundreds of its members jailed — there is a visible assertion and consolidation of the JI and other Islamists in post-Hasina Bangladesh. Within days of taking charge, Yunus lifted the ban on the JI.

It’s not just what researchers and security analysts who point out the Islamist angle. Ramachandran says that MEA officials also see such steps have provided a “boost to Islamists.” India’s experience in Bangladesh has made it wary of the rise of Islamists, pointing to the significant weakening of India’s security interests when Islamists were operating freely in Bangladesh.

Anti-India insurgent groups operated freely in Bangladesh in this period, Pattanaik said, recalling the landing of ten truck-loads of weapons and ammunitions meant for the United Liberation Front of Asom, a banned Indian secessionist organization, at Chittagong. “These are facts that remain deeply etched in India’s memories” of Bangladesh when Islamists had a free run in that country.

In post-Hasina Bangladesh, Islamists have stepped up their anti-India propaganda. They were “behind the propaganda that India caused the floods that hit Bangladesh soon after Hasina’s ouster,” Pattanaik said. While India’s “unwavering support” for Hasina’s autocratic rule is mainly responsible for the widespread anti- India feeling in Bangladesh today, stoking of such sentiment by the Islamists has undoubtedly fuelled the fire. India, the Awami League, and Hindus have become synonymous in the narrative in Bangladesh today, Pattanaik said.

For India the choice could not be clearer. Considering Hasina had consistently stood by India, in times good and bad, the question of giving up on her did not arise. And India had to live with the consequences, just as many countries in similar positions have. But how India manages the situation is also important.

It was after four months of seeking refuge in India, that Bangladesh sent a diplomatic note asking New Delhi to send her back. India confirmed receipt of the extradition request. “We confirm that we have received a note verbale from the Bangladesh High Commission today in connection with an extradition request. At this time, we have no comment to offer on this matter,” MEA spokesperson Randhir Jaiswal said.

But by that time Sheikh Hasina had already made multiple public statements condemning the interim government headed by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus. The Indian Express reported that on August 13, in her first statement since fleeing Bangladesh, Hasina issued a clarion call for justice. “I demand punishment for those responsible for the killings and sabotage, through investigation… I sympathise with those like me who continue to live with the pain of losing near and dear ones. I demand a proper investigation to identify those involved in these killings and terror acts, and appropriate punishment for them.” 12

Then in November-end, she condemned the monk’s arrest and the murder of a lawyer in Chittagong. “A top leader of the Sanatan religious community has been unjustly arrested. He must be released immediately. A temple has been burnt in Chittagong. Previously, mosques, shrines, churches, monasteries and homes of the Ahmadiyya community were attacked, vandalised and looted and set on fire. Religious freedom and security of life and property of people of all communities should be ensured,” she said in a statement released by her party1.3 Hasina also issued statements, either through her US-based son Sajeeb Wazed or through the Awami League’s social media accounts.

Finally, in early December 2024, in her first public address (online) after fleeing Bangladesh, Hasina accused Yunus of perpetrating “genocide” and failing to protect Hindus and other minorities: “Today, I am being accused of genocide. In reality, Yunus has been involved in genocide in a meticulously designed manner. The masterminds — the student coordinators and Yunus — are behind this genocide.” She had also alleged that police personnel, members of minority communities and Awami League leaders were killed during the protests, and “mosques, shrines, dargahs, churches and Buddhist places of worship” were attacked. While Hasina was delivering the speech, irked protesters in Dhaka vandalised and set on fire her father’s and Bangladesh founder Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s residence1.4As expected, Dhaka protested and asked New Delhi to stop her from making “fabricated” statements.

Given the above, it is not difficult to see that Hasina’s presence in India and her public statements have strained India-Bangladesh ties since her seeking refuge in India. It is reported that Bangladesh interim government’s Chief Advisor Prof Muhammad Yunus had flagged this concern during his meeting with Foreign Secretary Vikram Misri in Dhaka on December 9.

While describing the India-Bangladesh relationship as “very solid” and “close”, Yunus had asked India to help clear the “clouds” that had cast a shadow over the relationship in recent times, according to his office. Yunus’s office had said he also raised the issue of Hasina1.5“Our people are concerned because she is making many statements from there. It creates tensions,” he had told Misri.

If New Delhi did the right thing in giving shelter to Hasina with all the security arrangements, it wasn’t appropriate for her to issue such statements that would make her hosts’ position difficult, and further impact bilateral ties.

While an India-Bangladesh extradition treaty does exist, it has provisions for refusing requests, including if the offence is of “political nature”, or an accusation has not been “made in good faith in the interests of justice”, or military offences which are not “an offence under the general criminal law”. As of now, India is exercising the first principle of deft diplomacy that is expected in this regard: it had offered no further response to the note verbale.

Adding to the strain, Bangladesh has been rolling out a series of curbs on Indian exports since late 2024, including a ban on Indian yarn through five major land ports, restrictions on rice shipments, and import bans on a wide range of Indian products, from paper and fish to powdered milk. Dhaka also imposed a new transit fee on Indian goods, set at 1.8 taka per tonne per kilometre.16

Almost a year later, in the third week of April 2025, India reportedly halted about Rs. 5,000 crore of funding and construction work on key railway connectivity projects in Bangladesh citing concerns over ongoing “political turmoil” and “safety of labour”. These projects were part of an initiative aimed at enhancing connectivity between India’s mainland and its seven northeastern states through Bangladesh.17

A month later, on 18 May 2025, India imposed sweeping restrictions on imports from Bangladesh via land ports, a move that could disrupt goods worth $770 million, nearly 42 per cent of total bilateral imports, according to a report by Global Trade Research Initiative, a trade focused think tank1.8Under the new measure, major Bangladeshi exports such as garments, processed foods, and plastic goods will be channelled through ports of Kolkata or Nhava Sheva in Mumbai, effectively cutting off long-established land based trade routes. One outcome of the above was that as many as 36 garment-laden trucks were stranded between Bangladesh’s Benapole and India’s Petrapole borders. The incident is significant. Quoting the Chair of the national textile committee at the Indian Chamber of Commerce, Times of India reports that “around 93% of the garments from Bangladesh arrive via land route. Of this 80% enter through the Bengal border”.19

Elsewhere at the Akhaura Integrated Check Post (ICP) near Agartala, hundreds of trucks carrying goods bound for Tripura have been forced to return after being denied movement clearance. The Akhaura landport serves as a key commercial gateway for Bangladeshi exporters into Indian states such as Tripura, Mizoram, Manipur, Nagaland, and parts of Assam. In the last financial year, Bangladesh’s exports through Akhaura touched Rs 453 crore, up from Rs 427 crore the year before—a testament to the port’s growing trade relevance. RFL Plastic, one of Bangladesh’s largest plastic manufacturers, has been among the hardest hit. “The Northeast market is now cut off. Shifting to seaports will escalate logistics costs and render trade unviable.”

Even trade in essential items has seen disruption. No trucks carrying fish crossed the border after Bangladeshi exporters reportedly failed to secure the necessary permits. According to estimates, fish and dry fish worth $90,000 to $95,000 are exported daily to India via Akhaura. With mounting trade losses and rising frustration on both sides of the border, traders have called for urgent diplomatic intervention to find a middle ground that can sustain the vital economic corridor between Bangladesh and India’s Northeast.20

While India took a few months to impose non-tariff barriers, Bangladesh’s response to India’s May 18 restrictions has been swift. Days later, Bangladesh cancelled the $21-Million order given to Garden Reach Shipbuilders & Engineers Ltd, a government owned entity. The construction and delivery of one advanced ocean-going tug was to be designed, built and delivered in 24 months. The order was from the Directorate General Defence Purchase, Ministry of Defence, Bangladesh.21

This may essentially be viewed from the Islamist perspectives. Indian analysts are warning of the implications of the rise of Islamist and anti-India politics in Bangladesh for India’s security interests. Violence and instability in its neighbouhood are concerning for India as it has cross-border implications. It is anybody’s guess that Instability in Bangladesh could spill over into India through the porous borders.

In a Seminar on “India-Bangladesh Relations: Past, Present & Future”22 organised by the Centre for Economic

and Social Progress (CESP), on January 16, 2025, featuring four stalwarts from India’s diplomatic world – Deb Mukharji, Shivshankar Menon, Shyam Saran and Jaimini Bhagwati – Mukharji shed light on the religious and cultural divide in Bangladesh and the role of Islamists. He said there are two distinct streams in Bangladesh that had never been reconciled; and it was called the spirit of 1947 versus the spirit of 1971.

“That dichotomy continues, and a lot of people had hoped that the spirit of 71 would prevail permanently, but that has not happened and today the spirit of 47 is certainly striking back. That is the issue today. In fact, one of the major student leaders who attended a Jamaat rally in Dhaka admitted publicly and clearly that Jamaat helped them in their movement against the government; that they advised them, and they guided them. So, what is happening today (and) what people are worried about is a complete takeover by the spirit of 47. Now we have to see how this unfolds because it is still very open, and nobody really knows where this is going.”

Mukharji also added “Jamaat-e-Islami is a very powerful Islamist organization with a huge cadre, and they are the ones who provided the storm troopers for the agitation in the latter part of the agitation and violence; and they also died in that process.

Jamaat-e-Islami today is busy capturing institutions, and they are the force behind the Yunus government. Yet, they can never win an election. Even in Pakistan, with so much of Islamization, while the Jamaat can win a few seats they can never win an election. So Jamaat in Bangladesh is opposing early elections because they know that early elections were not going to help them. They want these things to continue so that they can capture institutions. And they are doing exactly what they have blamed Hasina for capturing institutions. And the Army is apparently now divided or polarized into three groups: one is pro Awami League, another is pro BNP, and the third one is Islamist.

Brahma Chellaney, Professor Emeritus of Strategic Studies at the New Delhi-based Centre for Policy Research and Fellow at the Robert Bosch Academy in Berlin, provides a more contextual 23 update as well explanation of the rise of Islamism in Bangladesh and what it could mean for India.

According to him, an unstable Bangladesh mired in radical Islamism and political violence has long been India’s geopolitical nightmare. Hasina may have forsaken her democratic credentials once in power but the “iron lady” also kept both the powerful military and Islamist movements in check.

He says, “To be sure, the interim regime is led by Muhammad Yunus, who was selected with the support of the student-led, Islamist-backed protest movement. But the 84-year-old Yunus has become little more than the civilian face of what is effectively military-mullah rule.

Hindus are under attack in Bangladesh. They have been the victims of jihadist mobs, which have also targeted other minorities, including Buddhists, Christians, indigenous people, and members of Islamic sects that Islamists consider heretical. At one anti-Hindu protest, Islamist marchers chanted, “Catch them and slaughter them.”

According to Chellaney, it is not difficult to see why Islamist violence is gaining ground. The interim regime has lifted bans on jihadist groups with links to terrorism and freed violence-glorifying Islamist leaders, including one who was convicted for the murder of a secularist blogger. Yunus’s administration also seeks to remove the reference to secularism in the constitution. All this appeasement has emboldened the Islamists, who have, at times, sought to enforce their own extreme vision of morality by hounding “immodestly” dressed women.

In the four months since Hasina’s ouster, hundreds of Bangladeshis have died because of violence. The situation has become so dire that even the secretary general of the Islamist-leaning Bangladesh Nationalist Party – the arch-rival of Hasina’s secular Awami League – has criticized the regime, lamenting that “people are shedding each other’s blood” on the streets and “newspaper offices are being set on fire.”

Chellaney points out that neighbouring India is watching events in Bangladesh with considerable apprehension (and, when it comes to attacks on Hindus, with significant anger). Fears are rising that Bangladesh will go the way of the dysfunctional Pakistan, a terrorist hub and key source of regional insecurity. If nothing else, India would face an influx of refugees. With millions of illegally settled Bangladeshis already living within India’s borders, this would present the country with an unpalatable choice between taking on more than it can handle and turning away people fleeing religious or political persecution.

India is also apprehensive that an Islamist ecosystem in Bangladesh could pave the way for a rise in Pakistan’s influence in Dhaka. In this regard, consider the recent docking of a Pakistani cargo ship at Chittagong port, the first in over 50 years. It is expected to pave the way for greater maritime contact and trade between the two countries. Will security cooperation follow? The possibility cannot be ruled out.

Worryingly also for India, Bangladeshi Islamists seem to have a good relationship with China. On the day of Das’ arrest, even as Chittagong’s streets were roiled with protests, Chinese Ambassador Yao Wen hosted a reception for leaders of Islamist parties, including the Jamaat-e-Islami and the Hefazat-e-Islam Bangladesh at the Chinese Embassy in Dhaka. India, whose contacts with non-Awami League parties are minimal, would have noted the engagement with concern.

We may now examine whether the “doctrine” followed by India in dealing with neighbouring countries has contributed to the upheaval in Bangladesh. According to Prashant Jha, there’s a new playbook that guides India’s relations with neighbours – what he calls “The Modi-Doval-Jaishankar playbook for the neighbourhood”.24According to him, “the core of this strategy — call it Plan A — rests on having a friendly regime in power in the vicinity, shaping politics in subtle, and sometimes not-so-subtle, ways to influence a favourable outcome, and using this proximity to limiting China’s ingress, and deepen economic, connectivity, commercial and people-to-people linkages.”

Another South Asia specialist, Partha Ghosh, however had pointed out serious limitations to this strategy. Writing just after the fall of Hasina government,25he says that even a great power like United States couldn’t ensure a friendly regime in China. He writes: “Dean Acheson, U.S. Secretary of State during the Harry Truman presidency, confessed about the limited efficacy of a foreign intervention.” And then tongue in cheek adds, “Obviously, his Indian counterpart, S. Jaishankar, must not have contemplated anything similar to that in Bangladesh. But what was expected of him was to alert his political bosses not to keep all the eggs in the Hasina basket.”

We can now return to Jha to get a glimpse of Plan B. He says that “If, largely due to domestic considerations and the rise of nationalism that often assumes an anti-Delhi tone, or Beijing’s direct intervention, an elected regime in the region adopts either a not-so-friendly or even a hostile attitude to India, Plan B sets in, which rests on maintaining a working relationship with whatever regime is in power, incentivising the regime with the lure of cooperation, showing very clearly the power of the Indian market and economic costs for that country if political or security redlines are crossed, and waiting for the opportune time to nudge domestic political processes in a more friendly direction.” 26

Very clearly, the various non-tariff barriers imposed by India on Bangladesh would fall in the Plan B category. Evidently, it is too early to figure out the efficacy.

In response to the recent terror attack on tourists in Pahalgam, Kashmir, India has decided to suspend the Indus Waters Treaty with Pakistan, heightening tensions between the two countries. This development has also raised concerns in Bangladesh, where there are growing fears that India might use water-sharing as a tool of political leverage. These concerns are particularly significant as the Indo-Bangladesh Ganga Water Treaty is set for renewal in 2026.

In an article in The Sunday Guardian, Tikam Sharma quotes noted water expert Nutan Manmohan saying “[W]ith the Ganga Treaty up for renewal next year, India’s suspension of the Indus Waters Treaty could cast doubts on its commitment to water-sharing with Bangladesh,”. Sharma then goes on to quote Uttam Sinha of the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA): “While India has traditionally respected water-sharing arrangements with its lower riparian neighbours including through the Ganga Treaty the success of future negotiations will largely depend on the prevailing political climate.” 27

Before we proceed further, we may refer to two things: the UN Convention on the Law of the Non- Navigational Uses of International Watercourses (Watercourses Convention) and Turkey’s practice.

The Watercourses Convention is a global framework for water sharing among riparian states. While it emphasizes equitable and reasonable use of water for all states, it doesn’t specifically differentiate between upper and lower riparian states. The Convention aims to facilitate cooperation and management of shared waters, requiring states to consult and cooperate on water management. But India is not a party to the UN Watercourses Convention. India abstained from voting on the convention at the UN General Assembly in 1997. While the convention aims to provide a global legal framework for cooperation on international water resources, neither China nor India have ratified it. So, whatever obligations India may have would be through specific treaties and agreements.

Now a little reference to Turkey’s practice. The Tigris and Euphrates rivers originate in the mountains of eastern Turkey. Together, they account for over 90% of Iraq’s freshwater and around 88% of Syria’s. Yet Turkey, sitting upstream, now controls the tap. At the core of this strategic control is the Southeastern Anatolia Project (GAP) — one of the world’s most ambitious hydropower and irrigation projects.

Launched in the 1970s, GAP includes 22 dams and 19 hydroelectric plants, most notably the Atatürk Dam on the Euphrates and the Ilısu Dam on the Tigris. While Turkey asserts that the project is essential for development in its southeastern provinces, the implications for its neighbours have been dire. Iraq, once known as Mesopotamia—the “land between rivers”—is now facing an existential water crisis. According to Iraq’s Ministry of Water Resources, water flow from Turkey has declined by more than 50% over the last four decades.28

President Erdogan has dismissed any let-up saying, Iraq and Suria do not have any claim to the waters of Tigris and Euphrates just as Turkey doesn’t claim their oil; though water and oil could be traded, clearly indicating the weaponisation of water as a geopolitical tool. It is another matter that he has called for India to lift the suspension of IWT.

Our intention in referring to the Watercourses Convention and Turkey’s practice is to suggest the possibility of India using the renewal of the Indo-Bangladesh Ganga Water Treaty as a geopolitical tool. However as of now, technical teams from both nations convened in Kolkata under the Joint Rivers Commission to specifically discuss the treaty’s renewal.

The Indo-Bangladesh Ganga Water Treaty, originally signed on December 12, 1996, by Indian Prime Minister

H.D. Deve Gowda and Hasina during her first tenure, guarantees a minimum flow of water to Bangladesh during the lean season. Spanning three decades, the treaty is set for renewal in 2026, subject to “mutual consent.”

Importantly, the renewal is not automatic. Mutual consent requires an agreement or understanding between both parties. Either side may choose not to renew the treaty if they deem it unnecessary.29

Myanmar

Since our coverage of Myanmar in the December 2024 issue of Policy Watch, the status of the Kaladan Multi Modal Transit Transport Project in Myanmar has assumed greater significance. The idea behind the project was straightforward. To create a transit corridor from the port of Sittwe in the Rakhine State in Myanmar to Mizoram, and eventually the rest of Northeast India. This would allow goods to be shipped from India’s eastern ports — primarily Kolkata — to Sittwe and then taken to Mizoram and beyond.30

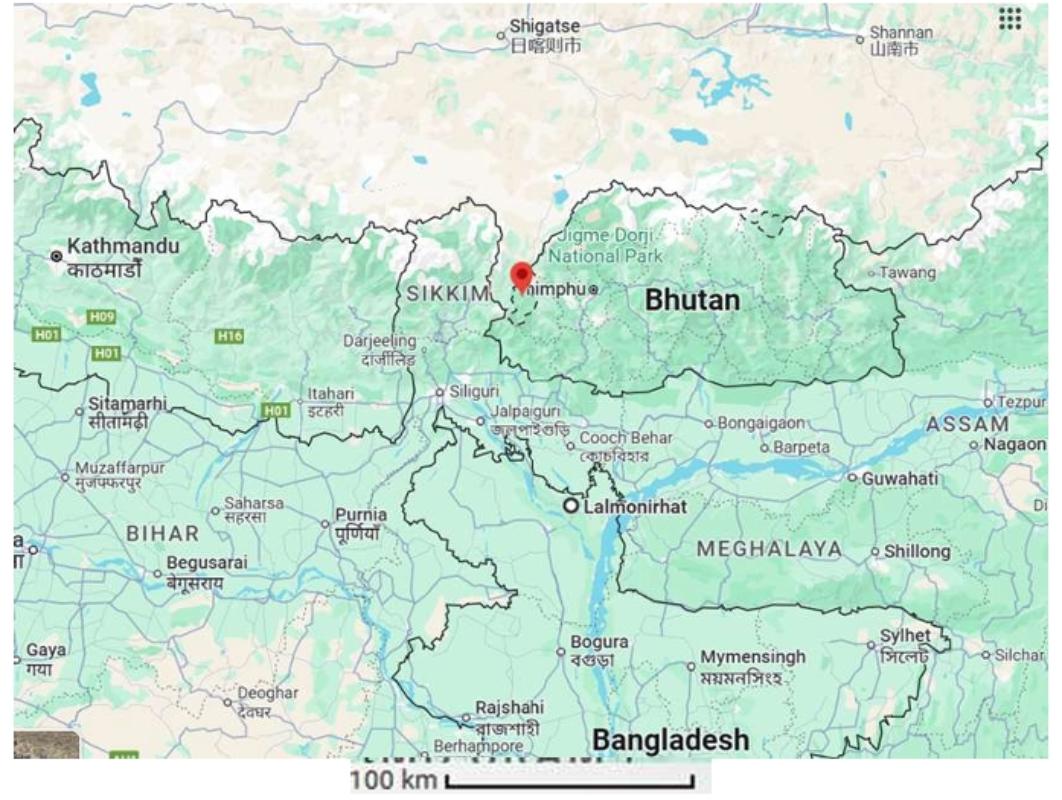

Much before Bangladesh interim government chief adviser Muhammad Yunus’s remarked in Beijing on 28th March 2025 that North-East India is “landlocked” and Dhaka is the “only guardian of the ocean for all this region, India had already rolled out the Kaladan Multi Modal Transit Transport Project (KMTTP) in Myanmar which is being funded by the Ministry of External Affairs. It connects the Kolkata seaport to the Sittwe port in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. In turn, the Sittwe port connects to Paletwa in Myanmar through an inland waterway and to Zorinpui in Mizoram through a road section.

Kolkata to Sittwe: This 539 km stretch between the two seaports will be covered by ship via the Bay of Bengal. Although this route has technically been operational for decades, India has invested significant resources to upgrade the Sittwe port to increase its capacity. This part of the project has been completed.

Sittwe to Paletwa: This 158 km stretch on the Kaladan river in Myanmar will be covered by boat. The MEA has invested in dredging the river, and constructing requisite jetty facilities at Paletwa to handle 300-tonne barges. The river is navigable and all work has been completed on this part of the project.

Paletwa to Zorinpui: This 108 km four-lane road will be the last leg of the corridor in Myanmar. Myanmar has granted all approvals for this part of the project, and the Integrated Customs & Immigration Checkpost at Zochawchhuah-Zorinpui has been operational since 2017. But the last 50-odd-km of this highway (from Kaletwa, Myanmar to Zorinpui) is yet to be completed. 31

Thereafter, the proposed Shillong-Silchar highway will act as a continuation of a key multi-modal transport project in Myanmar, offering a new sea-based route between the North-East and Kolkata, bypassing Bangladesh. The Central government had last month approved the first high-speed highway project in the North-East, a 166.8-km four-lane expressway from Mawlyngkhung near Shillong to Panchgram near Silchar along NH-6.

“With the help of the Kaladan project, cargo will reach from Vizag and Kolkata to the North-East, without being dependent on Bangladesh. The high speed-corridor will ensure transportation of goods via road after that, which will spur economic activity in the region,” the official said. By developing this alternative sea route via the Sittwe Port in Myanmar, India aims to reduce dependency on Bangladesh for access to the Northeaster region, countering the idea that Dhaka controls regional maritime access.

The problem is while the Indian government has official ties with the military junta, much of the territory that the Kaladan Multi Modal Transit Transport Project (KMMTTP) will cover has now fallen in rebel hands. While the Sittwe port is under the military junta, even the outskirts of Paletwas town have fallen to the Arakan Army in Rakhine (former name Arakan) state of Myanmar which is inhabited largely by the ethnic minority Rohingyas who are Muslim. However, the dominant group in the Arakan Army operating in Rakhine state is of Tibeto-Burman ethnicity practising Buddhism.

The Indian government has started backchannel talks with the rebel groups, but the ethic rivalry amongst various Chin rebel groups is unlikely to make it easy for the construction of 108 km four-lane road from Paletwa to Zorinpui in Aizwal. In other words, the fate of Kaladan Multi Modal Transit Transport Project hangs in the balance.

Partially to counter the anxiety related to this, the Government of India organised the Rising Northeast Investors Summit, 2025 in New Delhi on 22nd May 2025. In that Summit, MoUs for investments worth Rs 4.18 trillion were signed, including Rs 0.5 trillion by the Adani group and Rs 0.75 trillion by the Ambani group and Rs 0.3 trillion by the Vedanta group.32

China

China has long been a crucial actor in Myanmar, with bilateral relations greatly influenced by economic interconnectivity projects and a 2,185-kilometer shared border. The military junta took power in February 2021. They formed the State Administration Council (SAC), Myanmar. Since then, resistance to the SAC has grown. The Arakan Army based in Rakhine state of southwestern Myanmar on the border with Bangladesh, the National Democratic Alliance Army, and the Ta’ang National Liberation Army, in the Shan state of northeastern Myanmar, on the border with China, came together with some 15,000 fighters, to form The Three Brotherhood Alliance (3BTA). 33

They launched Operation 1027 on October 27, 2023 as an anti-SAC offensive in the Shan State. The offensive captured significant territory bordering China. In the wake of resistance offensive Operation 1027, China has played a role in the course of Myanmar’s future, by brokering a ceasefire across these warring groups.34

After the devastating earthquake in Myanmar on 28th Mar 2025, China provided immediate medical supplies and relief supplies. Then on April 10, China’s embassy in Yangon announced a pledge of 1 billion RMB ($137 million) in earthquake relief, stating “a friend in need is a friend indeed, and love knows no boundaries.” This pledge included 50,000 tons of fuel.35

On April 27, 2025, a delegation of the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami party proposed the establishment of an independent Muslim state in Rohingya-majority areas of the Rakhine State in a meeting with a three-member Chinese delegation led by Peng Xiubin of the South and Southeast Asian Affairs Bureau.

The Jamaat delegation head believes China can play a significant role given its strong relations with Myanmar, and reported the Chinese delegation assured the proposal would be conveyed to the Chinese authorities. Jamaat later retracted the statement, emphasizing they sought safe repatriation for Rohingya refugees3.6So China certainly appears to be fishing in the troubled waters of the Bay of Bengal.

The other development with respect to China has to do with the strategic significance of the access to the northeast states. During his four-day visit to China, from March 26-29, the Chief Adviser of Bangladesh’s interim government, Prof Muhammad Yunus, had remarked that “The seven states of [north] eastern India, known as the Seven Sisters, are a landlocked region. They have no direct access to the ocean,” Yunus had said. “We are the only guardian of the ocean for this entire region. This opens up a huge opportunity. It could become an extension of the Chinese economy — build things, produce things, market things, bring goods to China and export them to the rest of the world.”

The statement was understandably received with anxiety by India and invited adverse reaction. New Delhi terminated the transshipment facility for Bangladesh’s export cargo — a move that could potentially disrupt Bangladesh’s trade with several countries.

China’s involvement in reviving Bangladesh’s Lalmonirhat airbase of World War II era, near India’s ‘Chicken’s Neck’ corridor only 22 km wide, linking Indian mainland with the northeastern states, raises strategic concerns3.7 The airbase, near the vital corridor could increase vulnerability if used for military purposes. This development ties into China’s broader expansion of advanced airbases along the Himalayan frontier, including upgraded facilities near Doklam. The air distance from Doklam to Lalmonirhat is barely 150 km. the Chicken’s Neck would be vulnerable in case of any Chinese intrusion into Indian territory.

The Indian Army’s Trishakti Corps, headquartered at Sukna near the corridor, plays a key role in securing the region. This corps is equipped with state-of-the-art weaponry, including Rafale fighter jets, BrahMos missiles, and advanced air defence systems.38

Turning now to the western front, in the recent conflagration with Pakistan, both diplomatic and military equipment support by China stood out.

On the diplomatic front, the first report of the attack by Chinese state-run Xinhua on 22 April did not refer to it as a terrorist attack but as “tourists killed”, and an “ambush” in “Indian-controlled Kashmir”. The report was largely matter-of-fact and concluded noting that “A guerilla war has been going on between militants and Indian troops stationed in the region since 1989.” 39

It was only after the UN Security Council condemned the “terror attack in Indian-controlled Kashmir” that the headlines and text changed, and Chinese Ambassador Xu Feihong said, “Shocked by the attack in Pahalgam and condemn (it). Deep condolences for the victims and sincere sympathies to the injured and the bereaved families. Oppose terrorism of all forms.” 40

But China was also quick to add that it “hopes India and Pakistan will exercise restraint, work in the same direction, handle relevant differences properly through dialogue and consultation, and jointly uphold peace and stability in the region.”

According to Jabin T Jacob, Associate Professor in the Department of International Relations and Governance Studies, Shiv Nader University,

“This ‘neutrality’, however, does two things with respect to India. One, it hyphenates India and Pakistan in status as the Chinese – and Pakistanis – have always wished the rest of the world would. China does not see India as its equal or a competing power. New Delhi’s own difference in responses to provocations by China and Pakistan, in fact, tends to reinforce this perception. India had a rather weak-kneed military response following the Galwan incident in 2020. By contrast, it has been relatively more ready for kinetic responses to go with its rhetoric when Pakistan has been the aggressor.

“Two, Beijing is also shifting responsibility to India by urging “restraint” and asking both countries to “jointly uphold peace and stability in the region”. By calling for an “impartial investigation”, China is making clear that it does not buy India’s version of events. And nor can it do so, given that its rivalry with India is structural. Once again, Indian rhetoric and domestic politics involving Pakistan offer opportunities to China to exploit the India-Pakistan divide and to keep India off balance.”41

The second development with respect to China has been the first time ever use in active combat of China manufactured aircraft, missiles and air defence systems during the recent four-day military conflagration between India and Pakistan. A BBC report said while “[A] definitive account of what really happened in the aerial battle is yet to emerge… a Reuters report quoting American officials said Pakistan possibly had used the Chinese-made J-10 aircraft to launch air-to-air missiles against Indian fighter jets.”

While Pakistan rejoiced at their “achievement”, the BBC report went on to say that “some of the experts have called this a “DeepSeek moment” for the Chinese weapons industry” pointing out that “previously the Chinese weapon systems were criticised for their poor quality and technical problems” and referred to reports “when the Burmese military grounded several of its JF-17 fighter jets – jointly manufactured by China and Pakistan in 2022 – due to technical malfunctions, (and) the Nigerian military reported several technical problems with the Chinese made F-7 fighter jets.” 42

Pakistan

Here our focus is on the impact of Pahalgam tourist massacre and the ensuing four-day military exchanges on India-Pakistan relations, without going into the technical aspects, or who lost or did not lose what sort of military assets4.3 Instead we have limited our discussion to three key aspects: (a) shift in India’s response to terror attacks; (b) the messaging that India tried to convey; and (c) how the world perceives us and Pakistan.

The closure of Atari border affecting movement of trucks laden with goods and supplies, suspension of trade and travel and revocation of visas, including SAARC Visa Exemption, expelling military advisers in Pak embassy were all usual responses. The one unusual response of Indian government was the suspension of Indus Water Treaty – something that had survived three wars for over 50 years. That means India need not adhere to the allocation of the waters of the western rivers (Indus, Jhelum, and Chenab) to Pakistan as envisaged in the treaty. Although India does not have the infrastructure facility to store the waters as all the water projects are run-of-the river, even temporary stoppage or diversion can cause major water scarcity to the farmers of Pakistan side of Punjab.

Next, Operation Sindoor has redefined India’s approach. Harsh V Pant and Yogesh Joshi of Observer Research Foundation, New Delhi hold that, henceforth, India will treat Pakistan-sponsored terror as an act of war. And it will respond. Instead of mere threats, New Delhi has embraced a strategy of military escalation to impose consequences on Pakistan while maintaining dominance over the conflict. India believed that precision strikes and calculated escalation provided exit strategies for Pakistan’s military, allowing it to step back without losing face. Pant and Joshi also hold that, as a safeguard against prolonged resistance, India’s escalate-to-deescalate approach aims to pressure the international community, particularly the United States, into persuading Pakistan that continued retaliation is futile. If the international community fears nuclear escalation, New Delhi will use the strategic risk to its advantage.44

In June 2024, there was the Reasi terrorist attack in which several Islamist militants opened fire on a passenger bus transporting Hindu pilgrims from the Shiv Khori cave at Katra causing it to lose control and plummet into a deep gorge. The terrorists kept firing at the crashed bus. 9 people were killed and 41 injured. The Resistance Front (TRF) – an offshoot of Lashkar-e-Taiba – claimed responsibility but later denied involvement. The response of the government, including military establishment, was search and cordon operation.45

So, compared to the Reasi event, the messaging of Operation Sindoor was unmistakable: that terrorist activity will entail multiple military attacks deep inside Pakistani territory which while not targeting military or civil infrastructure will demolish known hideouts of militants. PM Modi in his televised speech made clear that acts of terror will be considered act of war; India will no longer distinguish between state actors and non-state actors; restrained but significant military action will be taken to destroy terrorists and terrorist infrastructure deep in Pakistan; blood and water cannot flow together; terror and talks can’t go together, and finally any discussion on Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) will only be on return of POK to India.

External Affairs Minister, S Jaishankar, echoed the PM’s stand. On May 15 he said: “Sometimes, the Kashmir issue is brought up. The only thing that remains to be discussed on Kashmir is the vacation of illegally occupied Indian territory in Pakistan-Occupied Kashmir. We are open to discussing that with Pakistan. I want to spell out our position very clearly… the government’s position is very, very clear.” 46

Finally, with reference to how the world perceives us and Pakistan, we could look at this from two angles: first the perception of where we stood in the world’s eyes and second what other nations said and did. About where we stand in the world of the perception vis-à-vis Pakistan in the context of recent military conflagration, we cite excerpts from an article47by Nirupama Rao, former foreign secretary and ambassador to the US:

“…In international crises, perception often becomes policy. In the recent flare-up with Pakistan, India demonstrated strategic restraint and military preparedness. But it struggled where it increasingly matters most: Narrative control. In the aftermath, Pakistan managed to reposition itself diplomatically, secure an IMF bailout and recast the conflict as one of two equals requiring mediation. India, despite moral authority and strategic strength, failed to convert these into a sustained global message. India ceded partial narrative control in this crisis and created space for Pakistan to punch above its weight in the information domain…

India’s media environment, particularly TV news, contributed to this slippage. Hyper-nationalistic coverage, marked by exaggeration and triumphalism, created a parallel reality that overwhelmed official channels…The global media, witnessing this, turned to other sources — primarily Pakistan’s well-coordinated messaging — for clarity. This created a perception gap: While India knew what it was doing, much of the world did not really know.

Despite India’s geopolitical heft, global media and diplomacy defaulted to old patterns: Calling for “restraint on both sides” and treating Pakistan as a co-equal party rather than a state sponsor of terrorism. That framing will not shift unless India takes ownership of its narrative. In the final analysis, India did not lose the moral argument, it lost the microphone…”

The Government of India has tried to correct this perception deficit, by putting together teams of political leaders from across Party lines and retired diplomats and sending them to selected countries. How much this will change the perception, time will tell but at least a step has been taken in the right direction.

The next point is what the nations of the world said or did. First, almost all nations condemned the terrorist attack at Pahalgam and expressed their sympathy and condolences. But except for Taiwan and Afghanistan, no country expressly endorsed India’s case that the terrorists were Pak based and trained and supported by its military, and India was legitimately placed to undertake military action. On the other hand, Turkey and Azerbaijan, both expressed support for Pakistan.48

Second, nations called both India and Pakistan for peace and cessation of hostilities, many invoking the horror of possible nuclear escalation. The hyphenation of India and Pakistan was back.

Third, even before ceasefire was announced by India and/or Pakistan, United States announced that it had mediated the ceasefire. Marco Rubio 49, US Secretary of State, made a press statement on May 10, 2025: “Over the past 48 hours, Vice President Vance and I have engaged with senior Indian and Pakistani officials, including Prime Ministers Narendra Modi and Shehbaz Sharif, External Affairs Minister Subrahmanyam Jaishankar, Chief of Army Staff Asim Munir, and National Security Advisors Ajit Doval and Asim Malik. I am pleased the Governments of India and Pakistan have agreed to an immediate ceasefire and to start talks on a broad set of issues at a neutral site. We commend Prime Ministers Modi and Sharif on their wisdom, prudence, and statesmanship in choosing the path of peace.”

India insisted that the ceasefire was a bilateral decision of India and Pakistan as an outcome of DGMO level talks. The statement of EAM S Jaishankar puts the issue in right perspective. During an interview with TV2 channel Denmark, he clarified that the ceasefire was brokered directly by Indian and Pakistani militaries, not external actors. Still, he welcomed any genuine global effort toward conflict resolution. “If you have a world leader who advocates settlement… that is to be welcomed.” 50

As Joshua White wrote in a commentary titled “Lessons for the Next India-Pakistan War”51 for the Brookings

Institution on 14 May 2025:

“It is too early to comprehensively assess what this means for India, Pakistan, and the region. But I think there are at least four dynamics coming into view that will shape the nature of future crises.

First, the global debate on “attribution” has tilted decisively in India’s favour, but in ways that may exacerbate political pressures to react hastily following future terrorist attacks.

Second, the two militaries have set troubling new precedents about target selection that will influence military planning and could raise the stakes for a future war.

Third, information operations appear to be moving from the periphery to the center of wartime planning, particularly within the Pakistani defense establishment.

And fourth, the widespread use of drones and loitering munitions has complicated how both militaries interpret the escalation ladder. Each of these developments could make the next crisis more unpredictable than the one we just experienced.”

Afghanistan

Just as India’s relations with Myanmar played a secondary role in the recasting of India-Bangladesh relations, the same was true for Afghanistan in the conflagration with Pakistan.

The relationship between Afghanistan and Pakistan has been problematic since ever. For a historical overview of this, readers should listen to Christine Fair, a US scholar on South Asian affairs in her talk to World Affairs Council in 2015 52. The Taliban returned to power in Afghanistan on August 15, 2021. Immediately thereafter, India pulled out all its diplomats and officials from the country. By June 2022, New Delhi had re- established diplomatic presence in the country by deploying a `technical’ team at the Indian mission in capital Kabul. And by January 2024, India was among 10 countries that participated in a Regional Cooperation Initiative meeting of diplomatic representatives convened by the Taliban administration in Kabul, reflecting the growing engagement between the two sides.53

On 17 May 2025, Kamaldeep Singh Brar reported from Wagah border that five trucks from Afghanistan, among more than 160 stranded between Lahore and Wagah border since April 24 and carrying perishable goods, crossed into India from the Attari integrated check post (ICP) in Amritsar Friday, 16th May — a first since the de-escalation of military tension between India and Pakistan after the May 10 ceasefire. A day earlier, External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar held his first-ever conversation with Taliban-ruled Afghanistan’s Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi and underlined India’s traditional friendship with the Afghan people and continuing support for their development needs…

Nearly 90 per cent of India’s trade with Afghanistan is routed through the Attari-Wagah border, which is also the only land link allowed for trade between India and Pakistan…Pakistan had suspended trade with India, including to and from any third country through its territory, on April 24 in response to the restrictions imposed by India following the April 22 Pahalgam terror attack that killed 26 people, most of them tourists.54

Afghanistan has been repeatedly bombed by Pakistan in the latter’s bid to destroy the strongholds of Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) which aims to overthrow Pakistan’s elected government to create an emirate governed by its interpretation of Islamic law. To achieve this goal, the TTP has attacked the Pakistani military and assassinated political figures. The first Pakistani airstrikes on Afghan soil came in 2022 and the second Pakistani airstrikes occurred in March 2024. The third and latest round of Pakistani air strikes on Afghan soil came in December 2024. Afghanistan had also responded with mortar fire, resulting in death and injuries to soldiers and civilians on Pakistani side.

However, Afghanistan’s adroitness in “sleeping with the enemy” is possibly a lesson for more mature nations. Soon after castigating Pakistan over the Pahalgam terror attack and supporting India in no uncertain terms, Afghanistan agreed to extend the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) to Afghanistan, marking a significant trilateral development amid ongoing regional tensions. This development was an outcome of a meeting in Beijing between Pakistan’s Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Ishaq Dar, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi, and Afghanistan’s Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi.55

For India, the trilateral meeting has come at a sensitive time, following India’s Operation Sindoor, which targeted terror infrastructure across Pakistan and Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. India has consistently opposed the $60 billion CPEC project due to its construction through Pakistan-occupied Kashmir.

Epilogue

The recent conflagration with Pakistan, though brief and quickly de-escalated, has changed not just the strategic doctrine of India’s response to terrorist violence but also unleashed a new set of military responses which involve use of new types of weapons and equipment such as deep-strike missiles and loitering munition drones. At the same time, the domestic political compulsions will make it necessary to match or exceed such responses. Coupled with tensions with Bangladesh and the menacing presence of China, in the entire arc from Myanmar in the East to Afghanistan in the West, we are entering an era of fragile peace in our neighbourhood.

China’s military and nuclear capabilities, already well above India’s, are also rapidly catching up with western state-of-the art technology. This coupled with its open support to Pakistan’s military programs, and Pakistan’s continued support to terrorist groups, and keeping the nuclear deterrence option open, shows that the India’s defence will remain a major concern for the foreseeable future.

6 Isaac Yee and Tanbirul Miraj, “Bangladesh prime minister flees to India as anti-government protesters storm her residence”, CNN, August 6, 2024 https://edition.cnn.com/2024/08/05/asia/bangladesh-prime-minister-residence-stormed-intl

7 Ibid.

8 Bangladesh skips India, reroutes global textile exports through Maldives”, The Daily Star, Nov 3, 2024 https://www.thedailystar.net/business/economy/news/bangladesh-skips-india-reroutes-global-textile-exports-through-maldives- 3743021

9 Ibid.

10 Biswendu Bhattacharjee, “Bangladesh assist commission office in Agartala vandalised”, The Times of India, December 3, 2024 https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/agartala/vandalism-at-bangladesh-assistant-high-commission-in-agartala-sparks-diplomatic- tensions/articleshow/115913076.cms

11 Sudha Ramachandran, “Bangladesh-India Relations Caught in a Downward Spiral”, The Diplomat, Dec 04, 2024 https://thediplomat.com/2024/12/bangladesh-india-relations-caught-in-a-downward-spiral/

12 Shubhajit Roy, “Bangladesh tells India to send back Sheikh Hasina for ‘judicial process’”, The Indian Express, December 24, 2024 https://indianexpress.com/article/india/cash-at-residence-supreme-court-justice-yashwant-varma-10019674/

13 Ibid

14 “Bangladesh to India: Stop Sheikh Hasina from making false, fabricated and incendiary statements”, Livemint, 6 Feb 2025 https://www.livemint.com/news/world/bangladesh-to-india-stop-sheikh-hasina-from-making-false-fabricated-and-incendiary- statements-11738851549041.html

15 Ibid

16 “India clamps down on Bangladesh imports as Dhaka tilts towards China: GTRI”, TOI Business Desk, May 18, 2025 https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/business/india-business/india-clamps-down-on-bangladesh-imports-as-dhaka-tilts-towards- china/articleshow/121246285.cms

17 “India reportedly halts Rs. 5,000 crore rail projects in Bangladesh, eyes Bhutan and Nepal alternatives”, MoneyControl, Apr 21, 2025 https://www.moneycontrol.com/news/india/india-reportedly-halts-rs-5-000-crore-rail-projects-in-bangladesh-eyes-nepal-and-bhutan- alternatives-12999196.html

18 Ibid

19 Ibid

20 “Bangladesh exports to Northeast hit roadblock as Centre closes key Tripura landports”, The Assam Tribune, 21 May 2025 https://assamtribune.com/north-east/bangladesh-exports-to-northeast-hit-roadblock-as-centre-closes-key-tripura-landports-1578210

21 Ann Jacob, “Bangladesh Cancels $21-Million Order From Garden Reach Shipbuilders”, NDTV Profit, 21 May 2025 https://www.ndtvprofit.com/business/bangladesh-cancels-21-million-order-from-garden-reach-shipbuilders

22 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pb0boQhPKBE

23 Brahma Chellaney, “Bangladesh’s Descent into Islamist Violence”, Project Syndicate, Dec 5, 2024 https://www.project- syndicate.org/commentary/trump-should-press-bangladesh-government-to-stop-islamist-violence-by-brahma-chellaney-2024-12

24 Prashant Jha, “The Modi-Doval-Jaishankar playbook for the neighbourhood”, Hindustan Times, Jan 9, 2024 https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/the-modi-doval-jaishankar-playbook-for-the-neighbourhood-101704791895308.html

25 Partha S. Ghosh, “Bangladesh: Beyond the Immediate”, The Wire, 12 Aug 2024 https://thewire.in/south-asia/bangladesh-beyond-the-immediate

26 Jha, op. cit.

27 Tikam Sharma, “Bangladesh concerned over water-sharing with India”, The Sunday Guardian, May 4, 2025 https://sundayguardianlive.com/news/bangladesh-concerned-over-water-sharing-with-india

28 Amit Singh, “Turkey’s weaponisation of water: A geopolitical tool in the Tigris-Euphrates basin”, Times of India, May 15, 2025 https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/blogs/mindfly/turkeys-weaponisation-of-water-a-geopolitical-tool-in-the-tigris-euphrates-basin/

29 Sharma, op. cit.

30 Arjun Sengupta, “Why Northeast-Kolkata link via Myanmar — not Bangladesh — is significant”, The Indian Express, May 19, 2025 https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/tasmac-case-as-supreme-court-frowns-at-ed-allegations-against-tamil-nadus-liquor- retailer-10022962/

31 Ibid

32 https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=2131072

33 https://www.brookings.edu/articles/operation-1027-changing-the-tides-of-the-myanmar-civil-war/

34 ibid

35 https://www.stimson.org/2024/major-events-in-china-myanmar-relations/

36 Ibid.

37 Dragon’s shadow near Siliguri? China aids revival of WW2-era Bangladeshi airbase near India’s ‘Chicken’s Neck’”, The Economic Times, May 18, 2025 https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/dragons-shadow-near-siliguri-china-aiding-revival-of-ww2- era-bangladeshi-airbase-near-indias-chickens-neck/articleshow/121246761.cms?from=mdr

38 Shivani Sharma, “India fortifies ‘Chicken’s Neck’ as Bangladesh, China eye strategic corridor”, India Today, April 4, 2025 https://www.indiatoday.in/india/story/india-fortifies-chicken-neck-as-bangladesh-china-eye-strategic-corridor-2703661-2025-04-04

39 Jabin T. Jacob, “Reading China’s Position on the Pahalgam Attack”, in Commentary, Centre of Excellence for Himalayan Studies, Shiv Nader University, 5 May 2025 https://snu.edu.in/centres/centre-of-excellence-for-himalayan-studies/research/reading-chinas- positions-on-the-pahalgam-attack/

40 Divya A, “Oppose terror in all forms: China; neighbours condemn Pahalgam attack, bat for regional peace”, The Indian Express, April 24, 2025 https://indianexpress.com/article/india/oppose-terror-in-all-forms-china-neighbours-condemn-pahalgam-attack-bat-for- regional-peace-9962009/

41 Jabin T. Jacob, op. cit.

42 Anbarasan Ethirajan, “Is China the winner in the India-Pakistan conflict?”, BBC, 20 May, 2025 https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c1w3dln352vo

43 There has been an outpouring of opinion pieces on the Pahalgam terror attack and the four-day military skirmishes between India and Pakistan. These include serving and retired generals, security analysts, political pundits, and foreign policy experts.

44 Harsh V Pant and Yogesh Joshi, “Post-Sindoor, A New Reality for India and Pakistan”, Observer Research Foundation, May 17, 2025 https://www.orfonline.org/research/post-sindoor-a-new-reality-for-india-and-pakistan

45 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2024_Reasi_attack

46 “Only thing which remains to be discussed on Kashmir is vacating of illegally occupied PoK”: Jaishankar”, The Tribune, May 15, 2025 https://www.tribuneindia.com/news/world/only-thing-which-remains-to-be-discussed-on-kashmir-is-vacating-of-illegally-occupied-pok- jaishankar/

47 https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/pakistan-india-military-preparedness-10021582/

48 https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/new-updates/will-continue-to-support-pakistan-in-good-times-and-bad-says-turkish- president-erdogan-amid-boycott-calls-in-india/articleshow/121177482.cms?from=mdr

49 https://www.state.gov/releases/office-of-the-spokesperson/2025/05/announcing-a-u-s-brokered-ceasefire-between-india-and- pakistan/

50 https://www.businesstoday.in/india/story/we-have-long-fended-for-ourselves-jaishankar-says-without-alliance-shackles-india-reads- global-chaos-with-clarity-477634-2025-05-24

51 https://www.brookings.edu/articles/lessons-for-the-next-india-pakistan-war/

52 https://youtu.be/WZLU6HsksU8?si=GmU9_b9V28Q_V5wz

53 Ranjit Bhushan, “India-Taliban thaw on Afghanistan: What really is happening?”, Hindustan Times, Feb 05, 2024 https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/indiataliban-thaw-on-afghanistan-what-really-is-happening-101707110103889.html

54 Kamaldeep Singh Brar, “Attari-Wagah border opens for Afghan trucks stranded in Pakistan; 5 cross over”, The Indian Express, May 17, 2025 https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/chandigarh/attari-wagah-border-opens-afghan-traders-huge-relief-10010252/

55 “China, Pakistan agree with Kabul to expand CPEC to Afghanistan”, Business Today Desk, May 21, 2025 https://www.businesstoday.in/india/story/china-pakistan-agree-with-kabul-to-expand-cpec-to-afghanistan-477199-2025-05-21