Abstract

India’s public health care system is considered as broken. This paper analyses the reasons thereof, and suggests policy options, governance mechanisms and development measures to set things right.

Evolution of Health as Right In October 1943, the Government of (British) India constituted a Committee to make a broad survey of health conditions and health organisations and to make recommendations for future developments. After an exhaustive three-year survey, the Bhore Committee (as it came to be popularly known) submitted its report that called for (a) integration of preventive and curative services at all administrative levels, (b) development of primary health centres (PHCs) in two stages, and (c) major changes in medical education which includes three-month training in preventive and social medicine to prepare “social physicians”. Almost without exception, experts in public health care underscore the continuing significance of Bhore committee report (Duggal 1991; Bajpai & Saraya 2011).

But it was the Declaration of Alma-Ata which was adopted at the International Conference on Primary Health Care (PHC), at Almaty, Kazakhstan in September 1978 that underlined the importance of primary health care. The primary health care approach has since then been accepted by member countries of the World Health Organisation (WHO) as the key to achieving the goal of “Health for All”.

Last year, member countries gathered in Astana, Kazakhstan to mark the 40th anniversary of the Alma-Ata Declaration and to affirm that strong primary health care is essential to achieve universal health coverage. Interestingly, while WHO had defined health as “a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”, Alma Ata extended WHO definition to include social and economic sectors within the scope of attaining health and reaffirmed health as a human right.

In India, the right to health is outlined in the Directive Principles of State Policy (Article 42 and 47 outlined in Chapter IV) and the Fundamental Right to Life as stated in Article 21.

The Contextual Reality

Just recently (July 30), The Times of India carried a front-page news of a poor tribal from a village – “which has never seen electricity, while nearest hospitals and schools are miles away and literacy is low” – in Rajasthan’s Banswara district selling his 12-year son for Rs. 30,000 to work as child labourer. This is not surprising and is in line with India’s ranking in 2018 Global Hunger Index where India was ranked 103rd out of 119 qualifying countries. The Global Hunger Index 2018 report was prepared jointly by global NGOs namely, Concern Worldwide (Ireland) and Welthungerhilfe (Germany). (Pruthi 2018)

The state of public health (PH) in India therefore cannot be appreciated unless pitted against the canvas of governance and development under the overall rubric of social justice. For the rich and powerful, issues of governance and development are not of concern; crony capitalism fashions them as per their needs. It is the poor and the marginalised sections of society who need governance and development to ensure their survival. And it is in this triad of poverty, governance and development that policies and practices in public health system in our country need to be fashioned.

Status of Public Health in India

While this is quite a complex field, for reasons of space we will restrict ourselves to a few parameters that give a fair idea of the state of public health. First, we focus on infant mortality rate (IMR) and maternal mortality rate (MMR). While India has made significant progress over the past few decades, the current IMR of 34 per 1,000 live births is still worrisome especially compared with our poorer neighbours like Sri Lanka (7.45), Bangladesh (26.9) and Myanmar (7.88). In the field of MMR, according to National Health Profile 2018 released by NITI Aayog in June 2019, India’s MMR is 167 per 100,000 live births. Here too, we compare poorly with Sri Lanka’s figure of 30 and China’s score of 19.6.

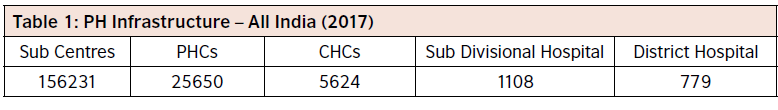

Second, we focus on infrastructure available for primary health care delivery system. Primary Health Care, or PHC, refers to “essential health care” that is based on scientifically sound and socially acceptable methods and technology, which make universal health care accessible to all individuals and families in a community. In India, we have a three-tier system that forms the core of National Health Mission which is derived from the Bhore Committee recommendations mentioned earlier. At the base, we have the sub centres (SC) covering 3,000 to 5,000 people, and primary health centres (PHCs) covering 20,000 to 30,000 people which are the first points of contact for the patients with the government health system meant to provide basic set of services, which includes conducting normal deliveries. If specialist requirements are needed, patients are then referred to the next tier: the Community Health Centre (CHC) which is supposed to have a physician, a gynaecologist, a surgeon and a paediatrician. If needs are beyond the capacity of a CHC, the patient is referred to the district hospital (called the tertiary centres). Table 1 provides a snapshot of PH infrastructure available in our country:

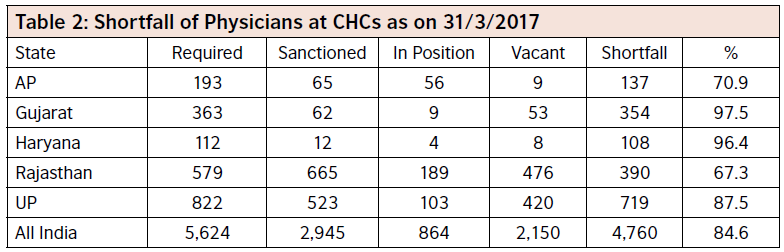

Third, we consider the availability of medical professionals. At the very basic level, the efficacy of structural arrangement is as good as the number of doctors available at these places. While the WHO has mandated 1 doctor for every 1,000 persons, the situation is quite alarming in our country, with just 1 doctor for 11,000 people. In Table 2, we have presented the data pertaining to some of the states in India:

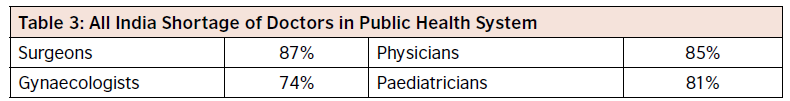

The figures for shortage of the four specialties mentioned above are given in Table 3:

Fourth is the question of poor quality of services. The recent deaths at BRD Medical College Hospital, Gorakhpur being one – when in August 2017, sixty-three children died at the hospital after the hospital’s piped oxygen supply ran out.

Dimensions 2 to 4 mentioned above severely impact the poor’s capacity to access healthcare services. According to Lancet study, while India has improved its ranking on a global healthcare access and quality (HAQ) index from 153 in 1990 to 145 in 2016, yet it ranks lower than neighbouring Bangladesh and even sub-Saharan Sudan (136), Equatorial Guinea (129), Botswana (122) and Namibia (137). Even conflict-ridden Yemen (140) performs better than India.

Fifth is the dumbing down of surveillance as a result of shift in focus from preventive to curative. As a result, we see incidents of chikungunya and AES resulting in many preventable deaths, as in the case of recent outbreak of AES in June 2019 that occurred in 222 blocks of Muzaffarpur and the adjoining districts in Bihar as a result of which 85 children died at the Sri Krishna Medical College and Hospital (SKMCH), one of the largest state-operated hospitals in Bihar. This is however a continuing trend. In India, preventive services take a back seat to curative care. Writing in The Telegraph (15 October 2006), TV Jayan points out that chikungunya and dengue are after all the outcomes of the shift in focus from surveillance and prevention (of vector borne diseases) to treatment and cure (when actually there isn’t any cure):

“…the first chikungunya case in Karnataka was accidentally spotted in November last year by researchers from the National Institute of Virology, Pune. The scientists alerted the state health department last year; but the state government took six months to act. The result was a whopping 7.5 lakh cases”.

Then again, he quotes an insect control expert who also heads a national laboratory:

“In the old days… insect surveillance was part and parcel (of program). Today, there is not a single entomologist worth the name. Even if somebody happens to be still employed they are (sic) either manning stores or are in charge of distribution of insecticides.”

Sixth is the related issue of absence of public health orientation in the planning, design and delivery of primary health care. For example, most states – more so the larger ones – experience significant regional variations in health outcomes. But rarely does the health plan of the Directorate of Medical Health of any state reflect this reality in terms of taking cognisance through monitoring, review and analysis, much less working out action strategies.

Impact on the Poor

In context of poverty, access to public health systems is critical. Yet we have simply not learnt although since 1990s, the public health system has been collapsing and the private health sector has flourished at the cost of the public health sector. According to Nobel Laureate Amartya Sen,

“in some ways we have gone particularly wrong here. I think public sector resources have to provide basic medical care for all, basic medicine, basic diagnosis, blood and urine tests, x-rays and so on, which go with the normal practice of medicine, and providing treatment for well known ailments and doing the best that the doctors can to help the patient, without going into an extremely expensive system of medical care… Rather than the public sector providing basic coverage to all Indian residents, you end up in a situation where a large proportion of the population remains underprotected by the public health sector.

We need a radical change in the way health delivery in the public sector occurs. India spends a lower percentage of GDP on public health than almost any other country, including those of similar income levels. The neglect here is massive, particularly because this has led to both the substandard delivery of public health and the development of an immensely exploitative private enterprise in healthcare that survives on the deficiencies — and sometimes absence — of public health attention.”

What does this mean in a country where as per government figures (IHP 2018; p. 50) 21.9% of the population is below the poverty line? Poverty and ill-health go hand-inhand, and limited income means a limited capacity for health spending. For the poor, therefore, health care is often the last priority, affordable only if there is money left over after paying for more immediate needs such as food. For rural poor households, illness represents a permanent threat to their income earning capacity. Research shows the enormous importance of health and health-related debt on the likelihood of slipping into poverty. Since the public health care system is so inadequate, patients end up with what’s known as out-of-pocket (OOP) expenses. OOP health expenses drove 55 million Indians – more than the population of South Korea, Spain or Kenya – into poverty in 2017, and of these, 38 million (69%) were impoverished by expenditure on medicines alone. These calculations by the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), an advocacy, were released on June 6, 2018, (Business Standard, July 19, 2018)

Besides, cost of medicines being so high, there is tendency on the part of the poor not to take the prescribed dosage, leading to recurrence of ailment and the disease becoming drug resistant. Absence from work leads to loss of income, and with OOP, the poor often fall in poverty trap. If we consider that 21.9% of Indians fall below poverty line (BPL), the tragedy that plays out due to poor primary health care becomes evident. It is in this context that India’s commitment to reduce inequality assumes significance. UK based Oxfam International’s “Commitment to Reducing Inequality (CRI) Index” ranks India 147th among 157 countries analysed, describing the country’s commitment to reducing inequality as a “very worrisome situation”:

“Oxfam has calculated that if India were to reduce inequality by a third, more than 170 million people would no longer be poor. Government spending on health, education and social protection is woefully low and often subsidises the private sector. Civil society has consistently campaigned for increased spending. The index finds that while the tax structure in India looks reasonably progressive on paper, in practice much of the progressive taxation, like that of the income of the richest, is not collected.” (The Economic Times, October 10, 2018)

Policy Implications

Given the above, we may cull out the following policy implications:

- Increase public spending on health: While studies have shown a direct linkage of health spending with health outcomes, India spends little on healthcare. As per official data released by NITI Aayog, India spend a low of 1.15 per cent of GDP in 2016. This is nothing short of a scandal considering the country sends mission to the moon. Consider also that WHO recommends that countries spend 4-5% of their GDP on health to achieve universal healthcare. Further, in most countries, the government takes the lead in social sector expenditure. For instance, in China, of the total expenditure on healthcare, 55 per cent is spent by the government. In the UK and Europe, government expenditure on healthcare is even higher at 75-80 per cent, whereas in India it is at a low of 31 per cent. This has resulted in poor state of India’s healthcare sector.

- Abolish User charges in government hospitals: For some years now, the government has been advocating user charges in public hospitals, arguing that while it is committed to basic health care (family planning, immunisation and selected disease programmes) people should pay for other services. This has been opposed by many health activists on the grounds that user charges actually reduce poor people’s access to essential services.

- Financial protection: A few years ago, this aspect has been well considered by a team of competent subject experts in a paper published by Lancet (Shiva Kumar, et. al: p. 675). According to them, the financial protection offered by (various government medical insurance) schemes remains insufficient. First, many schemes target only poor families; they are not universal coverage. Second, most schemes cover treatment costs of hospital admission or serious illnesses, and not outpatient care. Third, many of the schemes do not reimburse costs of drugs – a major out of pocket expenditure. So, among other things, they suggest universal financial protection based on single-payer system wherein the government would collect and pool revenues to purchase health care services for the entire population from the public and private sectors; establish uniform national standards for payment, and regulate quality and cost by use of appropriate information technologies. But from where would the money come from? They suggest increased taxation, especially on products that harm public health such as all tobacco products, alcohol, high calorie foods that have little or no low nutritional value, and energy inefficient and polluting vehicles.

- Replace CHC with satellite hospitals: The purpose of creation of CHC as the middle tier of public health care system was to relieve pressure from district hospitals. As early as twenty years ago, at the instance of the erstwhile Planning Commission, the Programme Evaluation Organisation (PEO) undertook a study to evaluate the functioning of the CHCs and their effectiveness in bringing specialised health care services within the reach of rural people. On the basis of data that PEO gathered, it concluded that the shortage of specialised personnel and equipment had made the CHCs as good as non-functional. If we compare PEOs findings with current data, we find the situation has only deteriorated: the shortage of health specialists and lack of equipment has only worsened, concomitantly increasing overcrowding and burden on district hospitals. So, as a policy measure it would make sense to replace a clutch of 4-5 CHCs in a region, free up the personnel and equipment and position them in a 300-bedded satellite hospital.

- Budgetary support for civil society working in health sector: The private sector won’t go to an area or sector where it can’t earn sufficient ROI, and the government’s outreach is limited by paucity of human and technical resources padded with the reluctance to serve in difficult terrain. In the process, the most disadvantaged are more excluded. In these inhospitable condition, NGOs and other civil society organisations have stepped in to render yeoman service. For example, Jana Swasthya Sahyog, an NGO, operates a hospital located 20 km away from Bilaspur town in the village of Ganiyari at the site of an abandoned irrigation colony that is leased to them by the Government of Chattisgarh. It has an operating theatre complex, diagnostic laboratory, and a low cost pharmacy, apart from a crèche. Since opening in 2000, over 100,000 patients have come for over 230,000 consultations. In 2008, there were 33,752 consultations at the Ganiyari OPD, and 40,155 total consultations, including the outreach clinics. There were 1286 inpatient admissions, and 1385 surgical procedures. A total of 49,007 investigations were conducted, 44,650 of which were at the Ganiyari laboratory. Since it is rendering a service which should have been rightfully done by the state, there is no reason not to extend them financial support and leave them to their own devices to raise resources. Since Jana Swasthya Sahyog is but one example, the policy implication is clear: make budgetary provision for civil society functioning, just as the government does for some of its own organisations, projects or schemes.

Governance

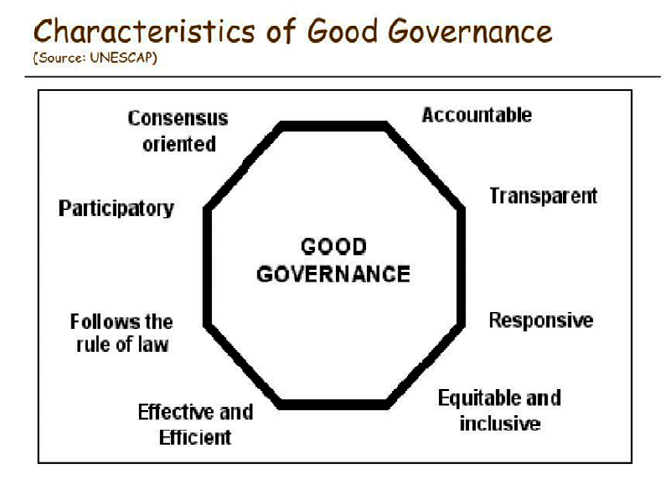

UNESCAP’s (2009) take on good governance is a useful guide for us to draw up an action

agenda to fix the broken public health care system of our country. While UNESCAP lists eight characteristics of good governance, from our perspective we can draw on some of those which have greater relevance. First, we may consider “accountability”. The starting point here is to strengthen the regulatory provisions. In a scathing op-ed in The Hindu, “No sweetening this bitter pill”, K. Sujatha Rao, former health secretary to the government of India makes a telling statement: “The absence of a well thought out policy framework for strengthening the health system is the most important issue facing the health sector in India”, and “unless the government regulates the growth of the private sector and makes it accountable, the worn down public health infrastructure cannot be revitalised”. She takes the example of government sponsored insurance scheme under which the government buys the insurance on behalf of the people for providing cashless service for inpatient care, the providers charge on a DRG basis, the insurance companies have assured incomes and the entire risk is borne by the government. While access has been increased, the scheme has generated fraudulent and corrupt practices, “with negligible impact on reducing catastrophic expenditure, impoverishing millions in the process”. The need therefore is to control provider behaviour through well laid down protocols and SOPs, penalties and incentive structures.

The next characteristic of governance in the context of our PHC system would be to make it equitable and inclusive. One way to achieve these is to ensure that it is participative, which is but another characteristic of good governance. These could be achieved by involving the participation of civil society in decision making and implementation process. Here, the participation of NGOs like Jana Swasthya Sahyog could play an effective role.

We would also need to consider two other characteristics of good governance. Our PHC system needs to be responsive as well effective and efficient. These could be achieved by “intensive use of technology that enables electronic transmission of samples for diagnosis at centralised laboratories, pricing of services, use of IT systems to closely monitor not qualitative but qualitative outcomes as well, put in place grievance redress systems, tightening and insulating the enforcement system at all levels”.

Capacity Building

Lastly, to augment the availability as well the quality of human resources in PH domain, it would be necessary to design and implement specific capacity building programmes in at least the following areas. Since AYUSH is already an integral part of PHC system, the Ayurveda specialists who are in any case Bachelor of Ayurveda, Medicine and Surgery (BAMS) can be trained in surgical procedures that are more appropriate at PHC level. Next, ANMs can be trained to become GNMs, and GNMs Nurse Practitioners. A very important agenda should be to mainstream public health discipline in the working ethos of general health practitioners if the space of preventive cure has to be reclaimed for effective delivery of universal health care. To ensure this, it should be made mandatory for every mid-level doctor to undertake courses – albeit short-duration – in any of the streams of PH that are more relevant for the design and delivery of universal health care.

Concluding Remarks

What have been mentioned in the foregoing sections have been well known, though this knowledge has been scattered across the spectrum. It would make sense not to scatter our energy and resources in mindlessly responding in knee jerk fashion but develop a cohesive strategic action frame, to be implemented in a realistic time-frame.

References

Bajpai, Vikas, and Saraya, Anoop (2011): “For a Realistic Assessment: A Social, Political and Public Health Analysis of Bhore Committee”, Social Change, 4(2): 215-231. www.indiaenvironmentportal. org.in/files/file/Bhore%20Committee.pdf

Business Standard, “Out of pocket health expenses plunge 55 mn Indians into poverty in 2017”, July 19, 2018. https://www.business-standard.com › Current Affairs › News

Central Bureau of Health Intelligence (2019): “National Health Profile 2018”, www.cbhidghs.nic.in/…/ National%20Health%20Profile-2018%20(e…/NHP%202018.pdf

Duggal, Ravi (1991): “Bhore Committee (1946) and its Relevance Today”, Indian Journal of Pediatrics, Vol. 58, No. 4, pp. 395-406

Lancet (2018): “Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016”, Articles| Volume 391, ISSUE 10136, P2236-2271, June 02, 2018, Published: May 23, 2018DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30994-2

National Health Portal of India, “Bhore committee, 1946”, nhp.gov.in/bhore-committee-1946_pg

National Rural Health Mission (2017): “District-wise Health Care Infrastructure”, https://nrhm-mis.nic. in/RURAL%20HEALTH%20STATISTICS/…/District-wise%20Healt…

Programme Evaluation Organisation (1999): Functioning of Community Health Centres (CHCs). planningcommission.nic.in/reports/peoreport/peo/peo_chc.pdf

Pruthi, Rupali (2018): “Global Hunger Index 2018: India ranks 103rd out of 119 countries”, https:// www.jagranjosh.com/…/global-hunger-index-2018-india-ranks-103rd-out-of-119…

Rao, K. Sujatha (2013/2016): “No sweetening this bitter pill”, The Hindu, Jan 29, 2013, Updated June 28, 2016, http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/no-sweetening-this-bitter-pill/article4354414. ece?css=print

Reddy, K Srinath, et al. (2011): “Progress towards Right to Health in India”, mimeo (part of it based on The Lancet India Group for Universal Healthcare, Lancet, January 2011.

Shiva Kumar, A.K., et.al. (2011), “Financing health care for all: challenges and opportunities”, under the series India: Towards Universal Health Coverage, Lancet, February 19, Vol. 377: 668-79. www. thelancet.com

The Economic Times, “India ranks among the bottom 15 of Oxfam inequality index”, October 10, 2018 https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/politics-and-nation/india-ran…

The Times of India, “Sold by dad for Rs 2.5k per month, child labourer says ‘that was going rate’”, Jul 30, 2019 UNESCAP (2009): “What is Good Governance?”, https://www.unescap.org/resources/what-goodgovernance

Varadarajan, Siddharth (2005): “India’s poor need a radical package: Interview with Amartya Sen”,

The Hindu, 9th January, http://www.thehindu.com/2005/01/09/stories/2005010900161400.htm