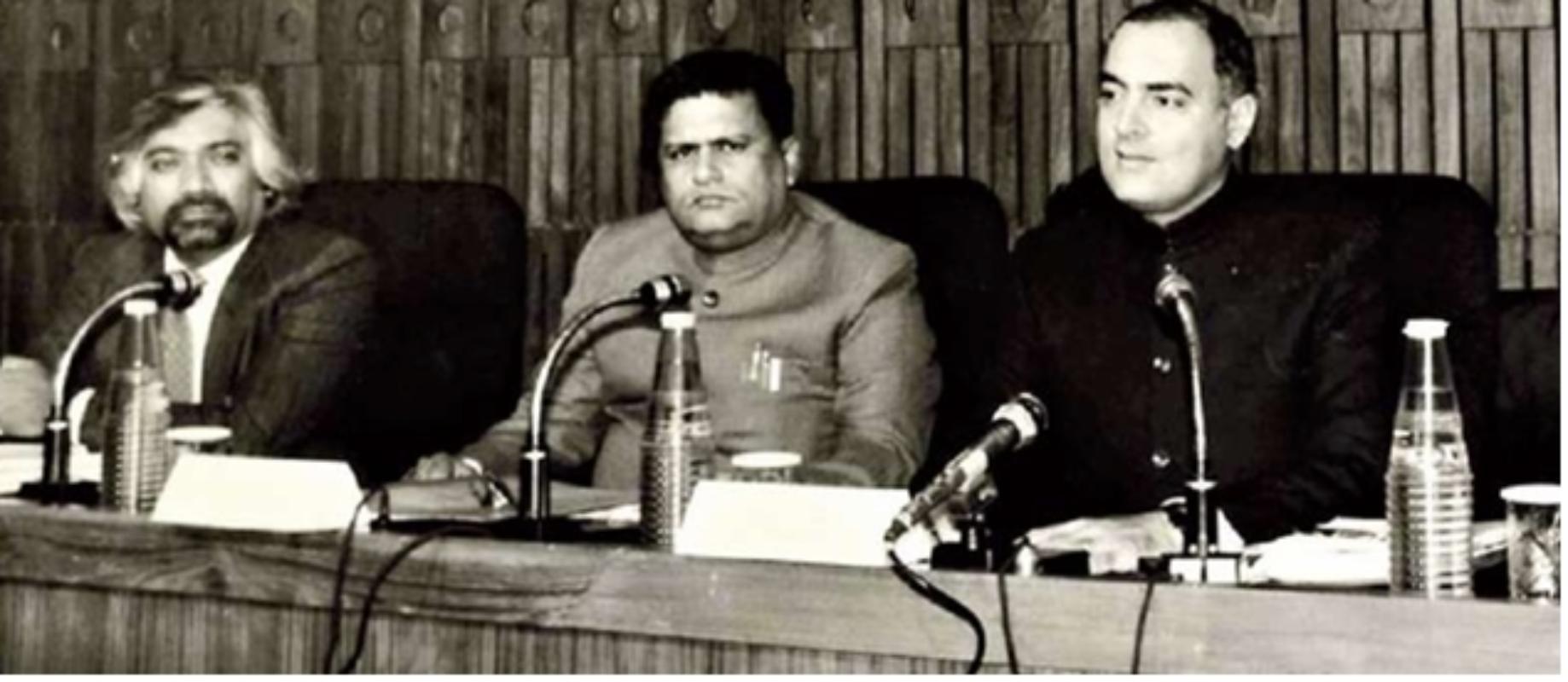

In the August of 1987, the initial three-year period for C-DOT was up. To mark the anniversary, we decided to present a report to the nation at Delhi’s big Vigyan Bhawan and give a live demonstration of our telephone exchange to the prime minister and others. We invited 1200 people from all over the country-businessmen, manufacturers, scientists, academics, government ministers, students and all the major media, in addition to Rajiv himself. The C-DOT teams from Delhi and Bangalore provided a live demo and displayed the exchange components and associated hardware we had developed.

I gave a little introduction at the podium. It was outlined in the ‘Report to the Nation’, as follows:

Mr Prime Minister, distinguished guests, and friends from C-COT, it is a pleasure to present a report to the nation on C-DOT’s accomplishments in the last three years. Perhaps someone might be curious to know why, when C-DOT has been an open book right through.

The answer is that this great nation of ours had reposed in us ‘super trust’ of developing a sophisticated digital telephone switching technology and products on our own from scratch for Rs 36 crores in thirty-six months. Now the question is, how far have we been able to come up to her expectations. Did we size up to it?

The questions posed are as difficult as the answers themselves. But our endeavour would be to answer these queries frankly and honestly for you to judge. According to us, the task was not, and has not been, a simple one, by any yardstick. In fact, for quite some time it was considered to be a great gamble by many.

However, we believe it has proven to be a great initiative on the part of the Indian system to challenge the genius and the drive of our young people.

The Centre for Development of Telematics was established on August 25, 1984 by the government with the following objectives:

To develop sophisticated telematics technology and products indigenously To digitize India’s telephone network to improve overall service

To be prepared for the integrated service digital network of the future

C-DOT is à scientific society funded jointly by the Department of Electronics and the Department of Telecom. The main goal of C-DOT has been to develop accessibility and rural communication with a focus on self-reliance, labour-intensive and capital-sensitive programmes.

At present, C-DOT has 425 people with an average age of 25 years. In Delhi, there are 215 working on software, systems and administration. In Bangalore, there are 210 people working on hardware and production. C-DOT has now developed small, medium and large rural exchanges, private automatic exchanges, and other exchanges for the digital networks.

In spite of all our accomplishments, we still have miles to go. We are conscious of the fact that designing a family of digital switching systems will not solve the telecom problems of India. We need to manufacture, install, maintain and service these systems for a long time to come. We recognize that qualified and dedicated people coupled with management skills to mobilize and motivate their capabilities are the ultimate limitations of development and not capital or technology.

Finally, we would like to thank our families for allowing each one of us to spend long hours at work, the media for fair coverage of our ongoing activities, and all those individuals, organizations and government agencies who have supported us.

Mr Prime Minister, please allow us to say publicly that without your personal involvement from 1981, our dream to build self-reliance in this vital technology of tomorrow as part of the ultimate goal outlined by our founding fathers of an independent India would have remained only a cherished reverie never to be achieved-but only to be deferred, delayed, distracted and dead.

Through your concern, commitment and continuing encouragement, it has been possible to deliver this development to the nation. Mr Prime Minister, thank you for your vision, support and presence.

Then one of the young engineers stood up and made a direct call to a colleague in Bangalore, the two describing and explaining the designs, the products, what they were and how they worked, all in clear layman’s terms, for the benefit of everyone in the hall. Then Rajiv spoke for fifteen minutes. He was impressed. Judging from the media accounts the next day, the entire country was impressed. I was proud of my team and very happy.

That was my concluding report on C-DOT, my way of saying: C-DOT is working well and it is on autopilot. This is the product and the process. Everything is on track and being implemented. Our engineers and administrators have the work in hand. Now it was time for me to move on.

It is an understatement to say that I was acutely aware of what my relationship with Rajiv Gandhi meant, not just in terms of the opportunities it gave me but also personally. I treasured that bond. His thoughtfulness towards me and, equally, towards Anu, was something that touched both of us deeply.

I started commuting to India in 1981, but decided to move my family there in 1985. Of course, doing that meant uprooting them, which gave me a deep feeling of anxiety. Salil was ten, Rajal seven. They had been born in Chicago, they were enjoying their schools, their family and friends. Chicago was their home. A big move was going to create a major disruption in their lives.

Anu herself hadn’t lived in India for about twenty years. How would she feel about moving? I thought that at the very least I had to introduce her to Rajiv, so she could see for herself why I wanted to do this, and could begin getting comfortable with the idea of this transition.

My chance came when Rajiv went to Washington to see President Reagan in June 1985. I didn’t have an appointment with him, but I called the Indian ambassador. ‘Please tell the PM that I’m going to be in Washington with my wife. We would very much like to meet him.’

The ambassador said, ‘There is no way you could do that. His schedule is solidly booked.’

‘I understand,’ I said. ‘But if you would please ask him. Just say that Sam Pitroda would like to see him.’ ‘Certainly,’ said the ambassador. ‘I’ll tell him.’

Anu and I went to Washington, not having any idea if Rajiv would be able to make the time. Three friends came along with us, Dr Prakash Desai, Rajiv Desai and Dr Divyesh Mehta. We were being tourists and seeing some of the sights, when I heard from the ambassador that Rajiv was free for half an hour- between Caspar Weinberger, the then defence secretary, and George P. Schultz, the then secretary of state. All of us were free to come.

The meeting was at the Indian Embassy. It took us a while to get through the heavy security, and as we walked in I saw Weinberger leaving. When we got to the meeting room, I said, ‘Mr Prime Minister, this is Anu.’

‘Anu,’ he said. ‘Welcome. Come, sit here next to me.’

I knew Anu’s heart must be racing. This was the prime minister talking to her, charming, good-looking, in such a warm and welcoming manner.

‘Anu, I know Sam wants to come to India. I want you to make sure the children’s admission to school is taken care of. It’s very important, and Sam may not understand these things in Delhi. Let me know. It’s essential to get them into the right school.’

He was speaking to Anu in exactly the sort of language she wanted to hear. I couldn’t help thinking what a truly exceptional person he was–what an effort he made and how relatable he could be.

Now, as I was finishing up with C-DOT, my relationship with Rajiv had only deepened. He would call me at night sometimes, at ten or ten-thirty. ‘Sam, come.’ So I would go with Anu to his home and we would talk, just the three of us.

But my personal feelings aside, I knew that my relationship with’ the prime minister had more or less given me carte blanche to take on whatever role I thought would make most sense post-C-DOT. I was thinking hard about how to bring technology to bear on India’s most pressing problems and what I might do to further that. We had talked about it. I was now beginning to get some clarity on what I wanted to do.

Additionally, I was part of the Scientific Advisory Council to the Prime Minister, chaired by Professor

C.N.R. Rao, a world-renowned scientist in the field of super conductivity and materials science.

Other members of the council were Dr Ganguly, Dr Tandon, Dr Mashelkar, Dr Narsimha, Dr Raha and Dr Lavakare-India’s most distinguished scientific minds.

These were the people who had spent their lives in research. As a scientist, I wasn’t anywhere near as accomplished as them, but I interacted with them regularly, so I was able to learn valuable lessons in agriculture, health, biotechnology, vaccines and other areas from them.

This group was always pushing for more research funds. But they also understood the need to use science and technology for the improvement of society. That was one of the main items on their agenda. What do you do with all this knowledge if not help the common man?

Being part of these discussions had helped me refine my ideas on the best ways to use technology to address specific problems. I was just about ready to make a proposal to Rajiv, when one evening I got a call from his principal secretary, Mrs Sarla Grewal. ‘Mr Pitroda,’ she said, ‘can you come over right away? We have an emergency on our hands.’

I was alarmed. ‘What’s happened?” ‘Please,’ she said, ‘just come.”

When I got to her office, she told me. “The PM is so angry, he just fired the secretaries of water and agriculture. He exploded at them.’

‘What do you mean “exploded” at them? Why? What exactly happened?’

“They were reporting to the PM on what they were doing about water and agriculture. He was so furious at their presentation that he fired them both on the spot. This hasn’t ever happened that the PM would fire two senior people like this. It will cause huge problems, big disruptions in those departments. I’m sure you can convince him otherwise. Please help.’

That same night I talked with the two department secretaries, effectively, the COOS of their ministries. But they didn’t have much to add to what Rajiv’s secretary told me. ‘We were making the presentation. The PM thought it was really bad quality. He just fired us.’

I called Rajiv’s office and told them we’d like forty-eight hours. Would his office please ask him to put the decision on hold for that time? Then I told the secretaries I wanted to meet with them the next day to better understand exactly what the problem was.

We decided to tackle the issue of water. ‘We’ve been asked to ensure adequate water supply for rural India,’ the secretary said.

‘All right. How much water is needed?’

‘Enough. Many places don’t have adequate water resources.

What kind of water are you talking about?” ‘Water.’

‘Let me ask you some questions. Do you know how much water a dog drinks?’ ‘What? What do you mean?’

‘I want to know. How much water does a dog drink, a buffalo, a camel, a cow, a cat, a donkey, a goat? How much do people need for bathing, how much for cooking, washing, drinking? Please get this information-then we’ll talk.’

The water secretary had simply not looked at the problem this way. He hadn’t broken the issue down into its component parts, which one would imagine would have been the first thing on his agenda. But he and the agriculture secretary were bureaucrats, not specialists.

They didn’t get into the details. They were responsible for planning, but they didn’t feel that a technical understanding was essential for the planning function, or at least for their function. In their presentation to Rajiv they had shown a kind of feel-good, advertisement-type video on India’s water and food production- pretty generalities with little substance.

Rajiv was a nuts-and-bolts kind of guy. I understood how those presentations must have infuriated him. No wonder he had stopped them midway and fired them.

I said, ‘Look, if you don’t break the problem down, how can you understand how much you need, and for what purposes? You’d require 20 litres per day, 50 litres, how much? And for whom?

There are almost exactly the same number of animals per village as people. You need to know how much water they use, how much the people use. You can’t plan without knowing these things. You certainly can’t report to the PM without specifics.’

Before long they came back with studies showing hard numbers on water requirement and use in the villages. They needed 30 litres per day per person, 40 litres for cattle.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘What are the problems? What do you need?’

They ticked off the challenges: Excess iron in the water supplies, excess fluoride, and occurrence of guinea worms coupled with high bacteria counts. They needed water-testing labs, geohydrological surveys, satellite imagery and education programmes.

It wasn’t that I knew much, if anything, about any of these issues. I was simply asking questions they hadn’t asked themselves before they put together their presentations. A whole new horizon had appeared in front of the officials. There was a lot of technology in water and, of course, in agriculture as well.

So we restructured the presentations together. Forty-eight hours later we sat down with the prime minister. They gave their presentations again, and this time he was happier with them. He took back their dismissals.

Thinking about all this, I concluded that now was really the time to look at not just telecom, but at some of the other areas I had identified in the paper I had done earlier, specifically in terms of where and how technology could most effectively impact development. Which of India’s problems were most amenable to generational change, and what kind of organization would it take to accomplish the transformations that might be achieved?

In fact, I was not the first to think along these lines. Several years earlier the national five-year plan had identified more than a dozen areas where science and technology could and should be fruitfully applied to national development. Moreover, the plan had discussed the efficacy of the ‘mission’ approach to addressing problems, i.e., utilizing special task-driven teams or organizations to accomplish specific goals.

The mission approach would bring management, coordination and motivation to the efforts, which, by their nature, crossed over bureaucratic boundaries.

Providing clean, adequate water, for example, involved the health, agriculture and education departments and others at the national, state and local levels. It required bringing scientists and technologists to focus their attention on specific problems.

The fact that there was no guiding, unifying force behind attempts to address these kinds of large problems meant that they typically got bogged down in a haze of territorial confusion and a multiplicity of priorities.

This resulted in a psychology of impotence and somnolence, with little or nothing actually getting accomplished. The mission approach was a potential cure for this malaise.

Even though the five-year plan had established a number of projects to cut through the bureaucratic tangle, they had gone nowhere.

Nobody understood them. Nobody was invested in them or wanted to take responsibility for them. They were, as one commentator said, ‘black boxes’. No one knew exactly what was inside them or how they were supposed to work.

But the five-year plan had suggested what the needs were and how they should be addressed. With this as a base, together with Rajiv, I decided that the missions should concentrate on five sectors: Rural drinking water, literacy, immunization, edible oils and telecommunications. Later, we added a sixth: Dairy production.

The National Technology Missions were launched to give new focus to development, where we shift from directing people to empowering them. These were launched in 1986-87, at the initiative of the then Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi.

The mission approach was required to create a sense of urgency, missionary zeal and infrastructure for technological self-reliance and improved delivery systems. It was also required to provide management focus, improved communication, improved centre-state coordination and organized information to substantially increase people’s participation.

The delivery of these basic needs required a unique integrated approach to make use of modern technology and tools to understand grass-root realities and the talent of our young intellectuals, professionals and technocrats.

It also required cooperation between the various agencies, the active participation of women as well as strong political commitment at the state and district level.

To succeed in these missions we needed to rejuvenate our existing institutions, simplify antiquated procedures, decentralize planning, mobilize available national resources, eliminate the duplication of efforts, provide modern management for motivation, mobilization and monitoring, and focus on quality and continuity; there was also a need to bring social auditing by people outside the system, and bring traditional community participation back into our mainstream.

I would come on as adviser to the prime minister for the Technology Missions with a ministerial rank. My overall objective would be to mobilize technology to benefit the people, especially the rural population and those in the sectors we had identified.

In addressing these six areas, I would attempt to integrate technological interventions with government efforts, private industry and volunteer resources. My job would be to coordinate the ministries and galvanize the work already being done.

I would keep everyone involved and focused on goals and timelines. I’d operate independently and bring in new methods of management. All these functions were right up my alley. I wasn’t a specialist in any of the mission areas other than telecom, but I could be the catalyst for all of them.

The first requirement was the staff, i.e., a secretary, someone I could rely on as a kind of ‘chief of staff. This was going to be a vast job. I had more or less created it for myself and I was ready to tackle it, but I knew I’d need someone with exceptional talents alongside me.

I found that person in Jairam Ramesh, a brilliant young man educated in India and then in the United States at Carnegie Mellon and MIT, specializing in engineering, economics, management and technology policy. Ramesh had been working as an adviser to Abid Husain at the Planning Commission, which had devised the five-year plan. Husain and I were close friends.

He was a colourful man with an open mind, a generous heart and a deep understanding of government institutions. He was a strong supporter of the Technology Missions concept, and generously offered me his advisership. Ramesh personified exactly what I needed he wasn’t just broadly knowledgeable, but full of ideas, energy, enthusiasm and drive.

Next, I hand-picked the mission directors. The team comprised Gauri Ghosh, Dr Misra, Dr Shenoy, Dr Rao, Dr Randhawa, Mr Narayan, Dr Kurien, secretary of health, Jairam, Dr N. Ravi and myself.

We now had in hand an interesting organizational structure. Each of the mission directors reported to their respective ministers: the immunization director to the health minister, the literacy director to the education minister, the edible oils director to the agriculture minister, and so on.

At the same time, however, their objectives were defined by the Technology Missions, and they were accountable to me as adviser. In this structure one of my jobs was to resolve conflicts. I met regularly with the various national Cabinet ministers and also with the ministers and chief ministers of each state.

My approach was to make sure the ministries got appropriate credit for our accomplishments, which had a beneficial effect all around.

In each of our mission sectors, my sermon was always that technology is an entry point to bring about generational change. Bringing the right technologies to the forefront would allow for radical new approaches to fundamentally transform existing conditions.

In the realm of water, for example, perhaps our most formidable problem was that there were over 100,000 villages without adequate sources of drinking water. Water had traditionally been located in these places mainly by dowsers and water diviners using age-old methods.

Instead, we called in space research experts to provide us with geohydrological mapping so we knew exactly where to drill wells. Our success at finding water sources went up exponentially. At the same time, we had to use technology and build plants to remove excess iron desalination many and fluoride from the water. We also had to build plants to get drinking water from salty seawater.

A large percentage of Indian villages had water sources, but not clean water. We identified 100,000 of these villages and set up testing laboratories in each district. We instituted standards and established treatment facilities. We had over 30,000 villages with guinea worm affecting people’s health, and education, training and safe wells were needed to avoid contracting infection through feet in water.

A major challenge was posed by the Mark 4 model water- pump that was used all over India. When these pumps broke down, they often stayed broken because the villages didn’t have people with the skills to fix them. Our response to this issue was to print and distribute many thousands of easy-to-understand repair manuals. We knew that when these got the right hands, a huge number of these Mark 4s would stay operational, significantly increasing village

water supplies across rural India.

We printed the manuals in each of India’s fifteen languages, Gujarati, Bengali, Oriya, Malayali, and the rest. But we had a major problem with distribution. When we shipped the leaflets, we feared the state minister’s office might keep 200 of the copies, the secretary might keep 100 and somebody else would keep fifty.

By the time manuals finally reached the right local officials, their number was vastly diminished-only a couple of hundred out of a thousand, not nearly enough. And then we’d face logistical errors such as the Kerala officials being saddled with the Gujarati-language manuals, and the Bengali officials getting the Malayali manuals. It was all simply a mess.

The first challenge for the Mission on Immunization wasn’t technological per se, it was infrastructure-, supplies- and decision- making-related. India’s record of childhood immunization was abominable. A large percentage of the children had never been immunized against measles/mumps/rubella. But polio was then a much graver problem. In 1987.

India had the largest number of polio patients in the world. Polio vaccines had been around for over thirty years, and we had still not been able to accomplish anything close to universal immunization. It was a national disgrace.

There was one simple bottleneck with regard to the polio issue-an ongoing conflict between those who wanted to use the Sabin oral vaccine and those who favoured the Salk injected vaccine. The two camps of physicians and medical scientists were fighting it out in public. The citizens, of course, had no idea what to think. Everyone was confused, and meanwhile parents lived in fear over their children’s health.

When we understood what was going on I called a meeting of seventy of India’s top immunization people. Jairam and I met with the assembled experts in Delhi. I told them, ‘We have three days. We won’t be leaving this place until we can tell the nation what our stand on the polio vaccine is. Are we going to go with oral vaccines, or the injected variety? But we need one voice. I’m not qualified, you are qualified. Now you have to decide.’

Dr Jacob Jones was an expert on vaccines, and he provided the necessary leadership during these difficult discussions. Everyone decided, finally, that oral immunization was preferable. The problem here was that the oral vaccine is a lower-virulence live-virus vaccine, which means it needs to be kept cold during transportation and storage.

It requires what is called ‘cold chain’ handling, which mandates the use of cold-chain equipment. But how do you get refrigeration into every part of India? So I called a meeting of industrialists at CII (Confederation of Indian Industries). The whole logistics of the cold chain had to be worked out.

And they did work it out. It took time to get everything in place and start immunizing, but the process worked its way through until almost Indian child had been immunized. And in 2013, twenty- five years after our intervention, India was finally declared polio-free.

The immunization intervention had other consequences as well. In 1987, when the Technology Missions were launched, India had zero polio-vaccination production capability. I wondered then: How is it that India has the world’s largest number of polio patients and perhaps the world’s largest population of children with polio, and we don’t produce a polio vaccine?

No one had an answer to that, so we did the research and I went to the prime minister. I told him it would cost us up to 300 million dollars to establish proper polio-vaccine production. When he approved the initiative, we sent teams to France and the USSR to study their methods. After that we drew up plans and the government made the investment. In a few years the company that had been established under the science and technology ministry was blending and producing all of India’s polio vaccine indigenously.

In fact, some of the problems addressed by the Technology Missions were as much societal as they were specifically technological- immunization, for example, and literacy. These areas often required a driving hand with strong political backing to break logjams and create new procedures.

In a broad sense, creating new processes to solve problems was itself a kind of technology, at least according to my definition. In my view, ‘technology’ encompassed the design of new production systems as well as breakthroughs or advances in hardware. Technology is not merely a device or a gadget. It is, at its heart, a way to solve a problem, whether it involves software or hardware.

The Mission on Literacy illustrated that. New devices were helpful here. We developed and put into production a solar-powered lantern, so that people in areas without electricity would be able to read and perform all their other functions at night with ease. We designed and produced plastic blackboards that performed much better than the traditional models and didn’t use up wood resources. But improving literacy was not primarily technological in that sense. Instead, it had to do with motivating people and providing training and materials-but most especially, it was about motivating people.

Vastly improved literacy (and numeracy) was crucial to India’s socio-economic development. But it was also a prodigious challenge. When the Technology Missions got under way the country’s literacy rate was at just about 50 per cent. Several hundred million adults were illiterate, the majority of them women.

The question was-What is the best way to attack this? Children were being taught to read in schools, but adult education depended on, first, motivating people to learn and, second, providing teachers and study materials.

With such vast numbers, it was clear to me that some kind of mass mobilization was necessary, which was not something the education department was set up to do.

The plan of action now included launching literacy campaigns throughout the countryside. We set up organizing committees and created a massive volunteer effort. We sent street theatre, acting, circus and music troupes into villages, endeavouring to teach whole populations about the importance of literacy in an entertaining, appealing manner. We wanted them to know what being able to read could mean for people’s economic lives and well-being.

With over 2 million committed volunteers, we flooded rural India with information. We set up continuing- education programmes in hundreds of districts. We made tremendous progress. In our initial years we began cutting substantially into the illiteracy rate.

In 1989, two years after we established our campaigns, the Technology Mission on Literacy was awarded UNESCO’s coveted Noma Literacy Prize. After the first year we understood a good deal about how to communicate to people the importance of literacy, and also how to teach reading to adults. At that point we began exploring how to grow and sustain these efforts.

The Edible Oils Mission was one programme where the primary motivation was economic. India had paid 1 billion dollars for imported cooking oils over the previous five years, even though there were significant areas of arable land suited for the domestic production of oil crops-soybeans, rapeseed, mustard seed and others.

But Indian farmers weren’t growing them. Instead, they were planting wheat, rice and other crops that gave them higher monetary returns. This situation, characterized by unfavourable economics for farmers, was partly due to the fact that the oil industry was controlled by a small number of powerful families and by the exploitative activities of multinational oil interests.

To reverse this situation I called on Dr Verghese Kurien, a legendary figure in the Indian dairy industry. Kurien had done his graduate studies in the United States, then had returned to India and become involved, by chance, in the field of milk production. When he started out, India was importing large volumes of milk and milk powder.

By the time I talked to him about the Technology Missions, he had turned the domestic dairy industry around to the point where India was exporting instead of importing milk. He had created a revolution. Under his guidance, some years later, India became the world’s largest milk producer, surpassing the United States.

Kurien was known globally as the ‘Father of the White Revolution’. He had created this near-miraculous turnaround by organizing farmers into large co-ops that could exert significant leverage on costs and prices, making milk production profitable for the small farmer.

Kurien was a straight-talking, take-no-prisoners kind of individual, capable of running roughshod over political and industry obstruction. He simply would not sit still and watch while large interests exploited the Indian farmer. Over time he had become an ally and a good friend. When I asked if he would join in on our effort on edible oils, he agreed.

Our challenge in this sector was to create an environment where small Indian farmers would see the advantages of planting oilseed crops. That meant restructuring the marketing system and making improvements in crop technologies. Kurien brought in some of the same methods he used to revolutionize the dairy industry: cooperative production and marketing, adherence to standards, support for individual farmers and protection against unethical competition.

Kurien was head of the National Dairy Development Board, which was sitting on large cash reserves. When it was announced that the board was going to throw its weight behind the intervention on oil, the market panicked. Kurien, the Cabinet secretary and I would meet regularly to decide how much oil we would buy and at what price. When that was announced, the market would adjust to our figure, to the benefit of the small farmers.

By 1990, instead of importing oil, India was exporting oilcakes at the rate of 600 million dollars a year. The turnaround was all due to applying appropriate management methods, understanding and information, and giving small farmers a little bit of support. ‘We move into areas where there is gross exploitation,’ Kurien told one interviewer, ‘and try to restructure the marketing system so that the small producer is not fleeced by middlemen or oil kings.’

When we started working on the oilseed mission, Kurien suggested that it would be a good idea to have a mission on milk as well. He had turned the dairy market around through the massive reorganization of producers, but milk production itself had plateaued.

A mission on dairy could mobilize the application of technologies to improve breeding, animal health and fodder production.

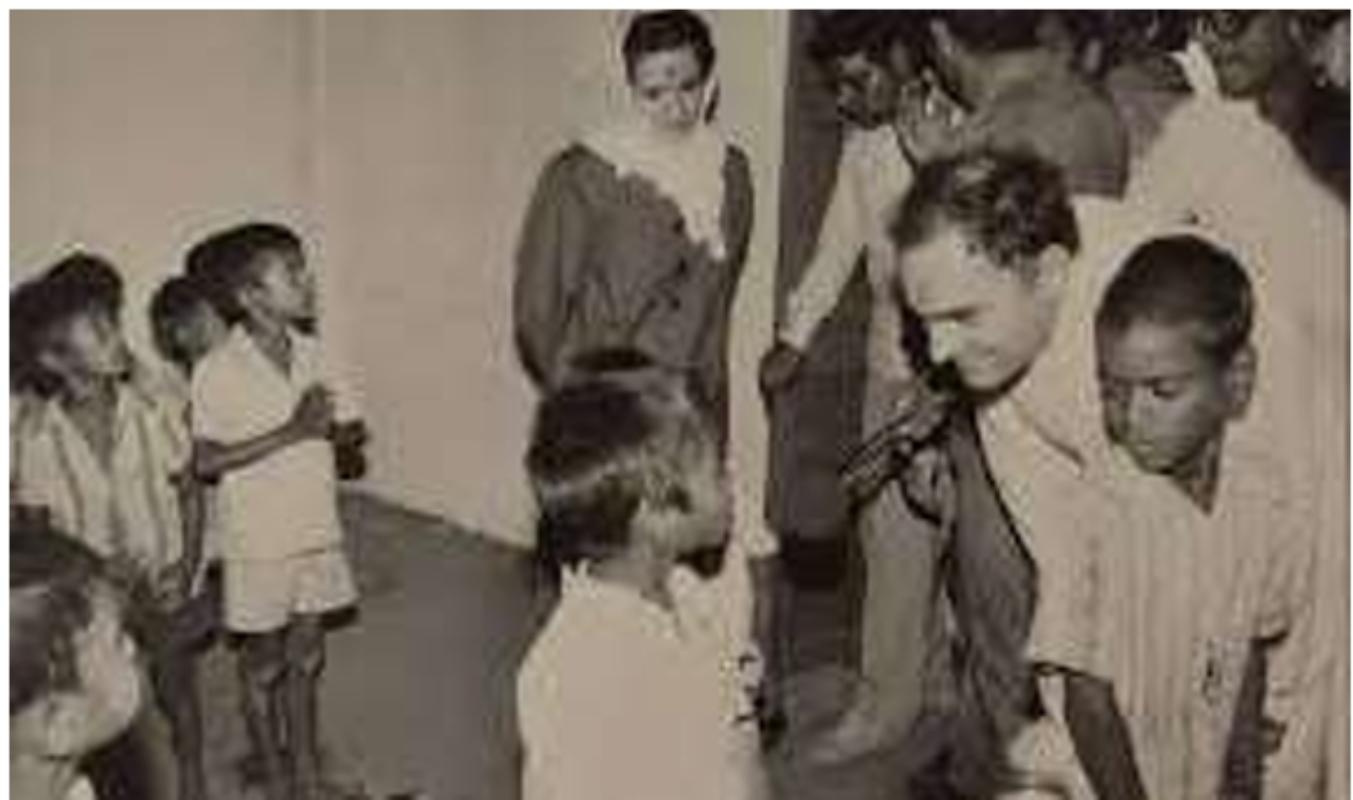

We could significantly enhance milk production. When we launched this mission Kurien invited me to his centre, where I met with 4000 dairy farmers. This was a man who operated on a scale that others could hardly dream of, but which was necessary if you wanted to fundamentally change Indian conditions.

So now we had six missions supported fully by the prime minister. As the missions got under way, all six mission directors-Jairam, myself and a couple of staff-started our crazy, hectic travels as a group. Jairam was my biggest asset. We went to a different state every week. The state’s chief minister would be waiting.

We’d meet with him and the heads of his departments to go through the missions one by one: What was happening in this state on drinking water, literacy, immunization, telecom, oils and dairy? Then we’d hold a press conference. With the chief minister sitting next to me, I’d announce where we were and what we were going to do.

Going public like this meant that everyone was aware of the projects we were undertaking and of our timelines for accomplishing them. This meant operating under scrutiny, with complete transparency and accountability. It meant that the state ministers were publicly associated with these projects and, along with us, would be seen as accountable.

This was a new thing for the local governments-somebody from the prime minister’s office coming in to review the situation and making press announcements. The media, of course, loved it and lapped it all up. And nobody could say no, because the prime minister was fully committed to the cause. All the chief ministers and other political bosses were very supportive of the Technology Missions and other initiatives of the Rajiv Gandhi government.

As the Technology Missions work advanced, the UN became aware of what we were doing. The concept of the missions seemed something that might be beneficial to development in other nations as well, and the UN convened a meeting on the subject in Poland.

I travelled to Warsaw for this and gave a series of talks, emphasizing on technology as the entry point for widespread development. The upshot of this was a UN report recommending every developing country to consider implementing the Technology Mission concept.

However, not all of our Technology Missions work was successful. We made an important impact in our six established areas-water, immunization, oilseeds, literacy, telecommunications and dairy. But my attempts to expand the missions to include environment, housing, floods and droughts failed to get off the ground.

Prime Minister Gandhi was in favour of the plans, but I found that political problems and conceptual differences among the relevant experts were too knotty to resolve easily. I was simply unable to negotiate the problems within a reasonable time frame. I didn’t give up on these, but I put off pursuing them until the point where we might be able to marshal more resources.

The Missions also generated substantial political and media controversy. Of the many projects we undertook, some simply did not work out. Critics would say that they succeeded only 60 or 70 per cent of the time-which they deemed a failure and the proof of a mistaken, poorly conceived diversion of government resources.

People take great pride in identifying problems. I always say that you do not need talent to identify problems in India. All you have to do is stand on a street corner and watch the scenes for ten minutes. You will perhaps be able to identify many of the challenges facing India merely in that space.

At times, even the solutions are staring right at you, however, we lack men and women with the domain expertise, leadership, ethics and courage to address these challenges against a potentially hostile bureaucratic environment and multiple odds.

People tend to shift the blame and believe that the problem lies somewhere or with somebody else, as opposed to looking within themselves to introspect and critique. At times, I found that what people think of as important is really not very important, and that what people think of as unimportant is extremely important.

During one of my trips as part of the Technology Missions, we went to a small village in Uttar Pradesh after visiting a local health facility, a school and a biogas plant. We were escorted to a big meeting organized by the head of the village, with almost 300 people in the audience.

In his speech, the village leader started complaining that the village doesn’t have a teacher, the doctor doesn’t come regularly, electricity is not available, and on and on. When it was my turn to speak, he was basically expecting me to say that I would go back to Delhi and promptly solve all their problems.

As opposed to this, I told them that these were their problems and that in a democracy one need to take charge themselves and begin to solve local problems with local resources. I told them to not await the central government’s help to solve every local problem. I expect my speech was not too well-received.

I continually tried hard to explain why I thought this kind of criticism was unjustified. My job, as I saw it, was not to ensure a 100 per cent success-rate. We were in the process of building a nation, not a company that needed to maximize its productivity and returns in order to survive and stay competitive.

Consequently, I wasn’t overly concerned if some of our initiatives didn’t work out. I could take responsibility when that happened, but ensuring success was not my goal. I was, if anything, more interested in the process than the product. My goal was to set up processes that were more effective than those currently in practice (which so often moved at a glacial pace, or all too often, not at all).

I was more affected and startled by the criticism of some of my friends, Rajni Kothari, for example. Kothari was the founder of the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, the person I had consulted when I was first developing the idea for C-DOT.

Kothari, a pre-eminent political theorist, was not happy with technologists who lacked what he thought of as cultural and philosophical depth. He also believed that working in partnership with the government was a waste of time that would, as he said in public, ‘tie you [Sam] in knots from which you will find it difficult to liberate yourself. Working in this way would be, he thought, a ‘kiss of death’. It was far better, in his opinion, to work from the grass-roots up rather than from the top down.

I thought Kothari was simply mistaken. He and many other leading thinkers were, at heart, anti- government people, which is why they made their intellectual homes in the think tanks and institutes. In that regard I had separated myself from them philosophically. I felt with absolute certainty that partnering with the government was the only way to make any real impact on a meaningful scale in a nation the size of India.

I felt very strongly that I had found the right niche for myself. I had certain specific skills in technology, in designing systems, in certain forms of management. I was highly driven and wanted to get things done, and I had developed a thick skin and the ability to project confidence, which helped me bring people along with me on the journey.

And through some luck, I had struck up a friendship with Rajiv Gandhi, which allowed me the backing and political will I needed. I also received a great deal of love, affection and support from the media and the public. People were very generous with their praise and appreciated my sincere efforts to help modernize India.

Doing all these things at once-travelling constantly around the country, meeting not just with India’s own top leaders but with international personalities as well-was a head rush. I was charged up-there were so many areas where I thought I could make a dent. I knew, too, that time was going to run out at some point, which injected extra urgency into our projects.

I could push this button, push that one-and every push could affect a million people, 5 million people. What a romantic thing to do, what a fulfilling thing to do-to make a difference in the fields of education, health, telecom, water and immunization for so many. I didn’t know what the future might hold, but for the moment, at least, I had found the right outlet for whatever compulsions were driving me-my need to fix things, my intolerance for political and bureaucratic dysfunction, and my dreams for a more progressive, more humane India.

3 From: Pitroda, Sam with David Chanoff (2015) Dremaing Big – My Journey to Connect India. Penguin, New Delhi