India has long striven to give itself a labour code that is good for labour and good for growth. By many accounts, historically, the labour code and the inspector raj it has spawned in implementation has had the effect of disguising employment/ driving employment into the informal unorganized/sector and some say even in driving large employment industries like textiles out of India. Less than 10 percent of employment is in the organized sector. For the balance 90 percent workers, working conditions are nowhere near what the country’s labour laws require them to be. E-commerce and platform workers, sometimes called gig workers, like those working with large and small companies delivering your daily or monthly requirements home or through taxi platforms, or food delivery (from restaurants) platforms etc. are similarly situated.

A new national employment policy is expected soon and is expected to go some way to include unorganized and gig workers. This policy may or may not set out a framework and rules for inter alia wage parity protection, working conditions, hours of work and leave etc. On the other hand, with increased longevity, massive migration and nuclear families, the need for social security and safety nets has increased manifold. The Government has come up with a whole slew of schemes to provide some social security for unorganized sector and gig workers on self-help basis supported by limited guarantees by the central Government (please see appendix for a description). The uptake has been patchy even as we don’t appear to have good quality data in this regard. Some platform players have been trying to think through this issue and a few have made some beginnings particularly in buying accident insurance and piloting life and medical insurance coverage paid for by the platform players. A petition has recently been filed in the Supreme Court asking the Court to direct the Central Government to extend social security benefits to platform/ gig workers.

The larger question of whether a broadening of the labour code in its current form to include platform/ gig/ unorganized sector workers at this time will be good for labour and business or should the Government nuance the new employment policy to push for graded mandates to have a better chance at improving formalization is very important and we should get a real conversation going on it among labour, contractors, platform workers and businesses that ultimately need this labour. Here we are limiting ourselves to focus on how e-commerce jobtech/platform companies might start to provide social security benefits to gig workers including leveraging Government schemes and the newly launched e-Shram portal (launched on Aug 26, 2021).

The overall cost of retirals (ESI/Medical, EPF/NPS, gratuity) works out to over 20% (some estimate this at up to 28%) of salary for blue collar workers in manufacturing industry and frontline workers in other industries in the organized sector. This does not include the cost of holidays, leave and days not worked whereas a gig-worker is often paid for actual days worked. At a high level, perhaps we need to explore two areas to make gig work equivalent in social security benefits to full time employment even as we preserve flexibility for workers and industry:

- Can gig workers be mandatorily enrolled into Government schemes without negatively affecting the growing employment opportunity through digital/platform play?

- Can we develop social security in sachets (or drops perhaps) and apply it to each unit of gig work.

-

Government Schemes

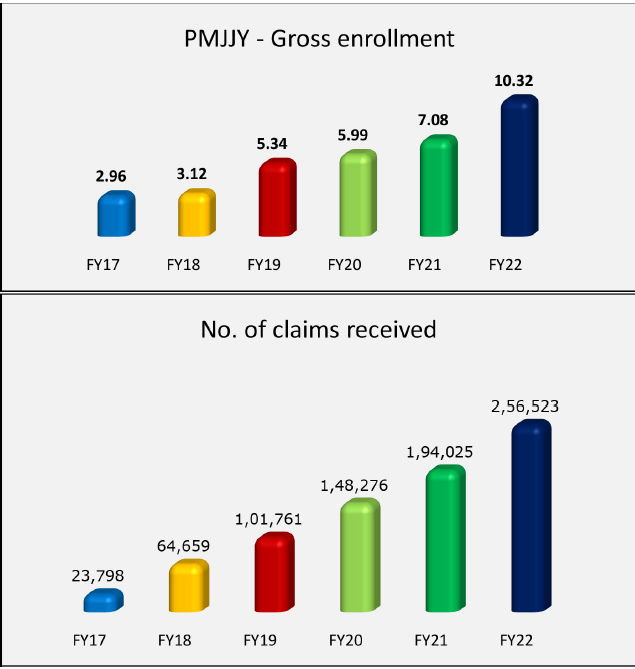

Life and Disability cover is available through PMJJBY. The data on the numbers enrolled is different on Department of Financial Services and IRDA site .

Source: Department of Financial Services. (https://dfs.dashboard.nic.in/). Data is cumulative.

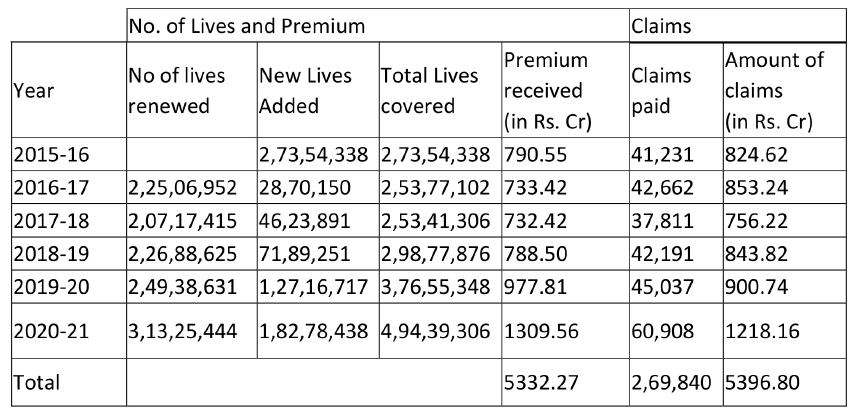

Source; IRDA (Response to RTI question in Parliament). Year means policy year ie June 1 to May 31. For 20-21, Claims are likely to be understated as the policy year is different and there is normally some delay in lodging claims.

IRDA numbers appear to reflect year on year data so based on this it would seem that about 5 Crore workers were covered as on March 31, 2021 under PMJJBY. The scheme is implemented by LIC and 9 private insurers for workers with bank accounts with 1200 banks (most of the coverage is through 28 large PSU banks and a few large private sector banks) that the insurer has a tied up with. The banks keep Rs 41 of the Rs 330 charged to the insured for a renewable life cover of Rs 2 lakhs. The insurance company pays for stamping etc (approx. Rs 40 one time) but otherwise has minimal operational expenses. Most insurers are likely losing money because as we can see collections are marginally less than pay outs, even without any margin for operational expenses.

Banks also apparently do not find the proposition remunerative perhaps because the unit cost of onboarding and operations are not covered by Rs 41 per person per annum. If we are to try to universalize this coverage, we will have to figure out how to reduce the operational costs of banks and insurance companies and perhaps also to raise premia to some extent (one estimate puts the requirement at 25% higher so a premium of Rs about 400 instead of 330). There is also the matter of the adequacy of the life cover at Rs 2 lakhs. There does not appear to be any explicit or implicit Government guarantee involved and apart from some losses being borne by banks and insurance companies, the worker is paying for this herself.

Even as these matters are sorted out, can we try to get all and any gig worker being onboarded by a platform player enrolled into PMJJBY? We are talking of Rs 330-400 per annum here as against a gig-worker’s wages for a month of work of Rs 8000-10000 at the lower end. Further, if she has such an account, can any pending payment be paid as soon as money starts to flow into her bank account to keep this insurance active year on year? I imagine, this may not be too difficult as e-commerce/platform/ jobtech companies already have a link with the payroll bank, each gig-worker has a bank account and e-kyc. So why is this not happening?

My conversations with bankers, insurance companies and some platform players suggest that aside from the poor economics for banks and insurers, the primary reason appears to be a lack of awareness about the scheme. There is practically no marketing about the scheme and its benefits (the Government does periodically put our some messaging but banks / insurance companies have no budget/ incentive to market. Further, we all know that financial products have to be ‘sold’. Typical insurance and mutual fund markets have grown because of systematic selling with hefty commissions for the selling organization/ agent.

The current PMJJBY has no provision for selling expenses. Finally, companies do not see any no imperative (the gig-worker wants money in hand, employer does not think its worthwhile bothering because of the churn which is anywhere from 50% – 150 % per annum), no compulsory mandate (as the gig-worker has to pay, even employers who wish to enable this scheme have provided this as an opt-in option). If there was a mandate, or even a focus by platform players, this could perhaps be provided as an opt-out option and then we may see much higher enrolment?

There does not appear to be any Government scheme for insurance against loss of wages in the event of an ill ness that does not lead to disability or unemployment. Micro insurer, Sewa Insurance has a scheme which provides up to 15 days of wage loss coverage with a payout of 200 rupees a day for a small premium and is a great start in this direction. Yet for such efforts to be universalized, a lot more work will need to be done and will likely require contribution/ backstopping by Government leading to further budgetary questions.

A Health and Maternity Cover is perhaps best addressed through ESIC which has a robust network of hospitals and clinics in the larger industrial areas where gig workers typical work. However, the 4% of wage contribution required to be paid by the employer under the ESIC Act is a dampener in a situation where a gig-worker does not have regular employment. It is worth considering if this residual (contribution for days not worked) cost can be borne by the Government. The Government is already bearing the cost of the Ayushman Bharat-Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB-PMJAY) which is administrated by the National Health Authority. A number of states have expanded coverage of their own accord. However, AB-PMJAY appears to be provided to a predetermined list and while many eligible people are not covered, there are also a large number of people who are not proposed to be covered. Does it make sense for the Government to extend this scheme to all unorganized sector / gig workers, with some contribution coming from employers to the extent of days worked.

For Pensions, the Government has launched Atal Pension Yojana(APY) and Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maan-DhanYojana (PM-SYM). APY was launched in 2015 for every Indian Citizen. Under this scheme, any Indian in the age group of 18-40 can enroll in this scheme and opt for a pension of Rs 1000-5000 per month. Based on the amount of pension so opted for and age at the time of entry into the scheme, a monthly / quarterly or annual premium is determined. Under PM_SYM beneficiaries are entitled to receive minimum monthly assured pension of Rs.3000/- after attaining the age of 60 years. The workers in the age group of 18-40 years whose monthly income is below Rs.15000/- can join the PM-SYM scheme. This is also a voluntary and contributory pension schemes and monthly contribution ranges from Rs.55 to Rs.200 depending upon the entry age of the beneficiary. Under this scheme, in the initial year(s) 50% monthly contribution is payable by the beneficiary and equal matching contribution is paid by the Central Government.

In both APY and PM-SYM, the Government of India guarantees the pension amount. APY is administered by PFRDA and operated by LIC, UTI and SBI while PM-SYM is administered by Ministry of Labour. It would seem to be a no- brainer for a gig-worker to enroll in one of these schemes but the enrolments are similarly low as for PMJJBY. The reasons also seem to be similar. A value for money in hand for the gig-worker over any future pension, lack of marketing and selling to help her understand the need because of a lack of marketing/selling budgets and the lack of a compulsory mandate. With inflation, there is perhaps a need to raise the monthly income bar to about Rs 25000 and age bar to 50 years to cover those who have worked the last 30 years without any safety nets. The Government’s contribution/guarantee can be limited to an upper limit in order to manage budgets. There may also be widows, old age pension schemes which will not be required if an APY, PM-SYM like scheme is adopted in wholesome measure.

2.Social Security top-ups in Drops / Sachets

Life and Disability Cover Top-Up

Can insurance companies design and administer an additional cover depending on the occupational hazard of the work (eg for riders/ drivers) which can be paid for by the employers on a daily/ weekly basis as a tiny drop and provides a top up on PMJJBY payouts in case of death/ disability. For example, a basic protection cover that may be a premium of Rs 10-20 a day and a graded pay out up to 10 lakhs based on typical days worked, age, occupation etc.

This may be targeted to give the family which has lost a bread winner earning Rs 8000- 20000 a month equivalent to two thirds of such monthly income. The costing here will have to take into account marketing and selling costs for such top ups to be bought. This may be seen as ‘good for business’ by ecommerce/ platform companies and/ or perhaps could be funded out of CSR budgets of corporates up to a limit. As the gig-worker acquires more responsibility she may wish to add her mite to this cover.

Pension/ Annuity

NPS is already designed to take periodic contributions. So all we need is a ‘drop’ that can be contributed by employers based on number of days of work. The aim would be to provide a top up to the gig-worker based on actual days worked and can be designed for equal or step up contribution by gig-worker and employer. The tech platforms already run the payrolls; unique, portable Aadhar/ e-shram IDs are available so the investments can be portable across regions and employers.

In conclusion, we feel that products would be reasonably simple to design and tech infrastructure exists to keep operational cost low. The real task perhaps is to get employers to acknowledge and embrace their role in building social security for their gig-workers. There is a need initially for marketing/ selling budgets and some operational budgets in terms of assisting employees in onboarding on e-Shram and enrolling for the Government benefits. Eventually, employers may find it worth their while to contribute to the top-up together with the gig-worker.

(The author would like to acknowledge inputs from the many colleagues who have kindly and thoughtfully provided inputs. The views expressed are her own)

Bharti Gupta Ramola was a partner at PricewaterhouseCoopers. She now serves on the Boards of a number of companies, social enterprises and works with some development NGOs.