In January 2019, RGICS began a research study to reconceptualise how planning and 1 development takes place as to address increasingly complex challenges in the country . The gravity of these challenges is highlighted by large scale long term migration from rural areas to 2 urban areas, against which the infrastructure in urban areas seems to be crumbling ; rising 3 unemployment ; breakdown of livelihood linkages and stark class inequality with wicked 4 regional patterns ; and drastically changing climate patterns with natural events having long return periods occurring rather frequently. The study, called Samarth Zillas, aimed to provide a regional approach to development (which is an old concept) and create a new framework keeping contemporary realities in focus. While the research report is forthcoming, this article aims to apprise readers of scope of the research study with a few pointers on major findings.

Samarth Zilla translates as ‘Capable District’. The capability of the district is to support and sustain its inhabitants with meaningful livelihoods and a decent quality of life. Although meaningful and decent may seem rather vague terms, assuming the least it could mean would deliver a livelihood that supports the person and his family well above the official poverty line; and with basic needs as defined by the person/ community including access to potable water, electricity, affordable housing, etc.

The Samarth Zillas framework uses a regional approach to development which recognises the continuum of rural and urban areas. Though the unit of planning could be larger such as a cluster of neighbouring districts, or a river basin, the Samarth Zillas framework makes a district as the unit of development because of data availability at district level as well as the existence of all implementation mechanisms. The framework deals with the whole district, instead of a town or a village, which enables larger, integrated planning and implementation. It borrows substantially from Sustainability Livelihoods Framework (SLF) so far as to include five types of capital (i.e. Natural, Human, Social, Physical, and Financial) and that these capitals are bound by certain constraints.

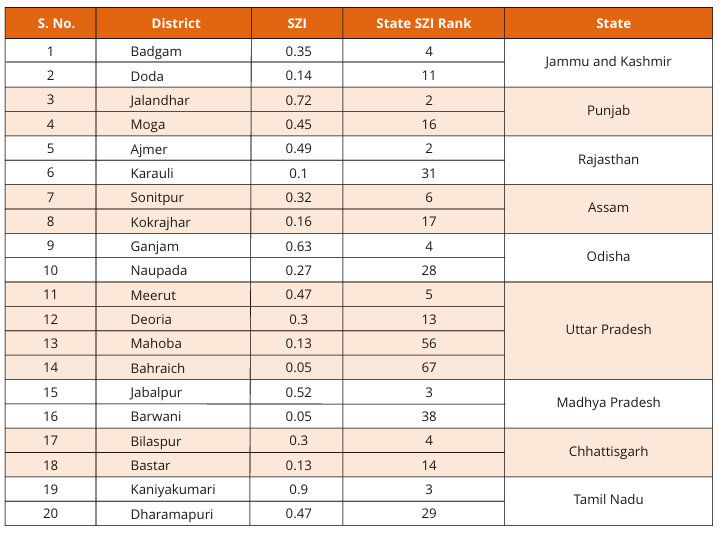

To guide the study, the Samarth Zilla Index (SZI) has been created using eight variables under six categories. These categories are institutional capability plus the five types of capitals. The usage of variables was restricted by availability of district level data, and the formats and timeframes in which it is collected. Based on the Index, a total of 20 districts were selected from 9 states across India (See Table 1).Within a state, the districts were chosen to represent agro climatic and economic variability, and both top and bottom performers. The selection of states was largely driven by operational convenience and networks available to carry out the research. During the study, one state, Madhya Pradesh, had to be dropped due to operational issues. Effectively, the study has been carried out in 8 states and 18 districts. More details on the Index and its construction in forthcoming final report.

Table 1 Districts selected for Samarth Zilla Study and their SZI scores.

Keeping in view the diversity of contexts offered by district under this study, the methodology adopted was simple and flexible, starting with assessment of status and potential of each district under each type of capital under SLF. Along with this, three dimensions of constraints over these five types of capital viz. political economy of the district, institutional capability, and financial feasibility, presented a reasonable picture of the nature of development or underdevelopment of the district along with the requirements to reach the assessed potential. Clearly, the research is largely qualitative with quantitative data used to support qualitative findings.

The study, in its final phase now, has thrown some interesting insights into the process of development, critical requirements to enable that process, and the path to Samarth-ness. Without delving into much detail, major findings can be summarised as follows:

- There is a process to capital formation. Only availability of abundant natural capital does not ensure that there will be growth of other types of capital in the region. Neither is it the case that availability of physical or financial capital leads to growth in any type of capital. There is necessity of ‘high quality’ human capital to come together, create social capital of a particular variety and act on natural or physical and/or financial capital.

- The process of capital formation is extensively guided by norms, values and belief systems of a given society or group of people. These norms vary spatially and among communities within an area too. Under such scenario, it becomes impossible to drive the process of capital formation with interventions guided by a normative system that does not align with the norms of the society. For smooth functioning of this process with a long-term view, it is imperative that developmental efforts align with the reigning norms. These norms, beliefs and values of the society are the institutions of the society or “Rules of the Game” with which the development takes place.

- When these norms, beliefs and values become divergent from that of the community/ society, it requires action on behalf of the community execute a course correction. This collective action becomes the soul of change process which keeps people’s requirement at the forefront, drives institutional development and change, and brings about acceptance to a certain set of norms and values across multiple stakeholders and actors. This collective action is a challenge, as often the boundaries of norms, belief and values are not definite. Within a community, there might be different sets of norms held closely while overall existing norms align with none of them.

- The institutions are the crucial link in driving the process of the capital formation and growth. Institutions ensure that the process takes place in an effective manner as per the needs of the people. When institutions are formalised and diversified, they carry out specified functions as organisations forming a network, which is guided by the institutions and also effect the institutions. This way, institutions of an area or region are in fact dynamic, although the change is visible over long periods of time.

- Although the government systems are uniform across the country, particularly within states, the intra and interstate variations in how these systems are operationalised to carry out governance of resources are huge. Given that agro-climatic and economic contexts, populations and nature of resources also differ greatly, adds to the challenge of governance.

- The governance challenge is further enhanced if we understand the responsibilities placed on the government structure, which certainly has deep limitations. The civil society organisations and market institutions work in different mutually exclusive domains altogether. The past efforts in creating mechanisms of engagement within these three sectors, such as the Public-Private-Partnership with government and market institutions as stakeholders, have seen limited success, raising questions on pattern of associations.

The Samarth Zillas research study, with few of the findings mentioned above, creates a framework synthesising all the learnings. The framework engages multiple stakeholders to create acceptance of a set of norms, values and beliefs which then guide formal/ informal and governmental/ non-governmental institutions to drive the process of capital formation and growth. The framework places emphasis on tri-sector engagements and partnership to create vehicle of delivering on felt needs of the people of a district/ area. This becomes necessary as the complex challenges call for complex solutions and partnerships. This article may raise more questions than it answers, please refer to forthcoming research report on Samarth Zillas framework for details.

Footnotes:

1 Vijay Mahajan and Yuvraj Kalia (2019) Samarth Zillas : A Regional approach to holistic spatial development http://www.rgics.org/wp-content/uploads/Policy_Watch_8.1.pdf

2 Yuvraj Kalia (2018) Understanding Urbanisation: A consultation at RGICS http://www.rgics.org/wp-content/uploads/Understanding_Urbanisation_Oct-18.pdf

3 Prasanth Regy (2019) Employment in India: Structural Problems http://www.rgics.org/wp-content/uploads/Employment-in-India-Structural-Problems.pdf

4 Livemint (2018) Where India’s affluent classes livehttps://www.livemint.com/Politics/DymS22taK4EyAbSYRx0rSO/Where-Indias-affluent-classes-live.html