Mani Shankar Aiyer’s “The Rajiv I knew” is a labour of love to set the record straight on India’s “most misunderstood Prime Minister”.

A close aide of Rajiv Gandhi who oversaw his domestic tours and his principal speech writer, Mani clarifies that, apart from Panchayat Raj and Apna Utsavs, he played no role in policy.

Mani, however, brings to bear a wealth of personal experience to shine a light on Rajiv Gandhi’s Prime Ministership, backing it with wide and solid research, a keen intelligence, persuasive arguments and occasional flashes of the wit for which he is known.

This is a serious book which makes a convincing case for a reassessment of Rajiv’s leadership. His term began with the largest electoral victory in independent India but, later, became mired in controversies which drowned out and obscured his many forward-looking initiatives.

These sought to heal political schisms, find solutions to violent conflicts, deepen grassroots democracy and propel India into the modern technological age.

Accords at home

Thrust into Prime Ministership in tragic circumstances and with little political experience, Rajiv brought a fresh perspective to bear on India’s problems of national integration. With the confidence of youth he believed that, given reason, goodwill and political accommodation, solutions could be found to democratically and peacefully end violent internal conflicts in Punjab, Assam, Mizoram and J&K.

The various Accords that he signed were a serious effort to address issues which had alienated sections of opinion within these states. Some of the Accords unravelled during implementation and could not be sustained.

In Punjab, for instance, the provisions of the Rajiv-Longowal Accord signed in 1985 remained a dead letter and, eventually, peace was restored by the crackdown by KPS Gill and the Punjab Police.

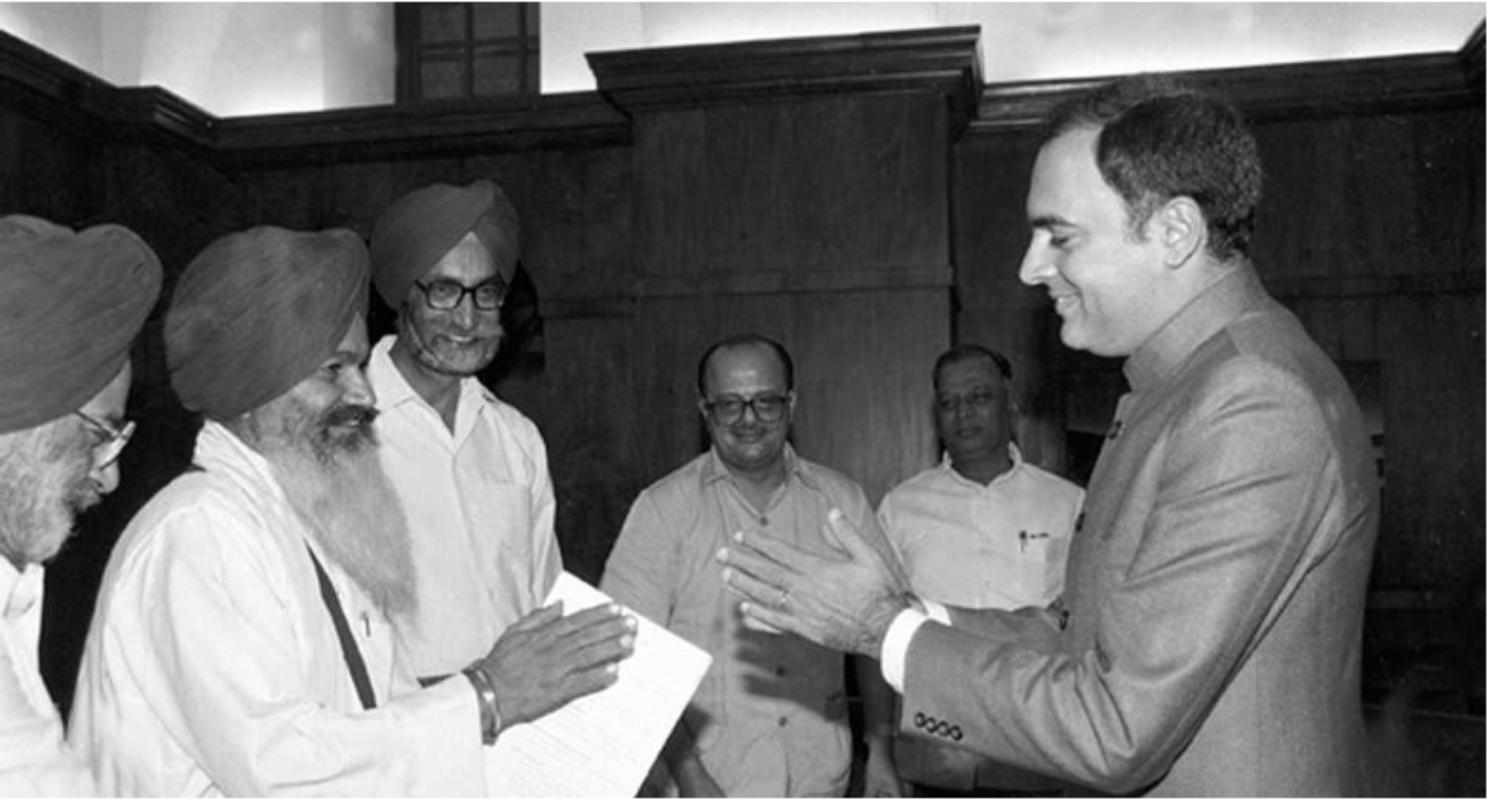

Despite the difficulties in implementing the Punjab Accord, Mani points out that Rajiv’s consistent actions, including the release of Sant Harchand Singh Longowal in January 1985, the signing of the Punjab Accord in July 1985, the holding of elections in September 1985, conceiving and executing Operation Black Thunder II which flushed out terrorists from the Golden Temple without casualties and his many fearless tours of the State changed the political atmosphere, helped restore government authority and set the stage for gradual restoration of normalcy.

A month later in 1985 the Assam Accord was concluded. Rajiv charged Home Secretary, RD Pradhan, to bring the All Assam Student Union to the negotiating table with the assurance that any agreement reached would be put to the test in free and fair elections, even if that resulted in a premature end of the Congress government. This brought about a sea change.

As Prafulla Mohanta and other student leaders of the AASU “took charge of the State Government, the violence that they had engendered petered out. The North East returned to the national fold…”

The Mizoram Accord, much of which had been negotiated earlier by G Parthasarthi under Indira Gandhi, was clinched under Rajiv and was, perhaps, his most successful Accord. Mizoram had seen one of the longest insurgencies in India, beginning in 1966.

The situation was complicated by Mizoram being a border state which shared borders with East Pakistan (later Bangladesh) and Myanmar, enabling the insurgents to slip in and out and to avail of ready support from the Pakistan Army.

As part of the political settlement in Mizoram, Laldenga’s Mizo National Front was persuaded to lay down arms in return for the Centre handing over the post of Chief Minister to Laldenga and getting the Congress’ duly elected leader, Lalthanhawla to step down and become Deputy Chief Minister.

Since then, the MNF and Congress have alternated in power in Mizoram. The former insurgents have embraced the democratic process and, today, Mizoram is the most peaceful state in the North East.

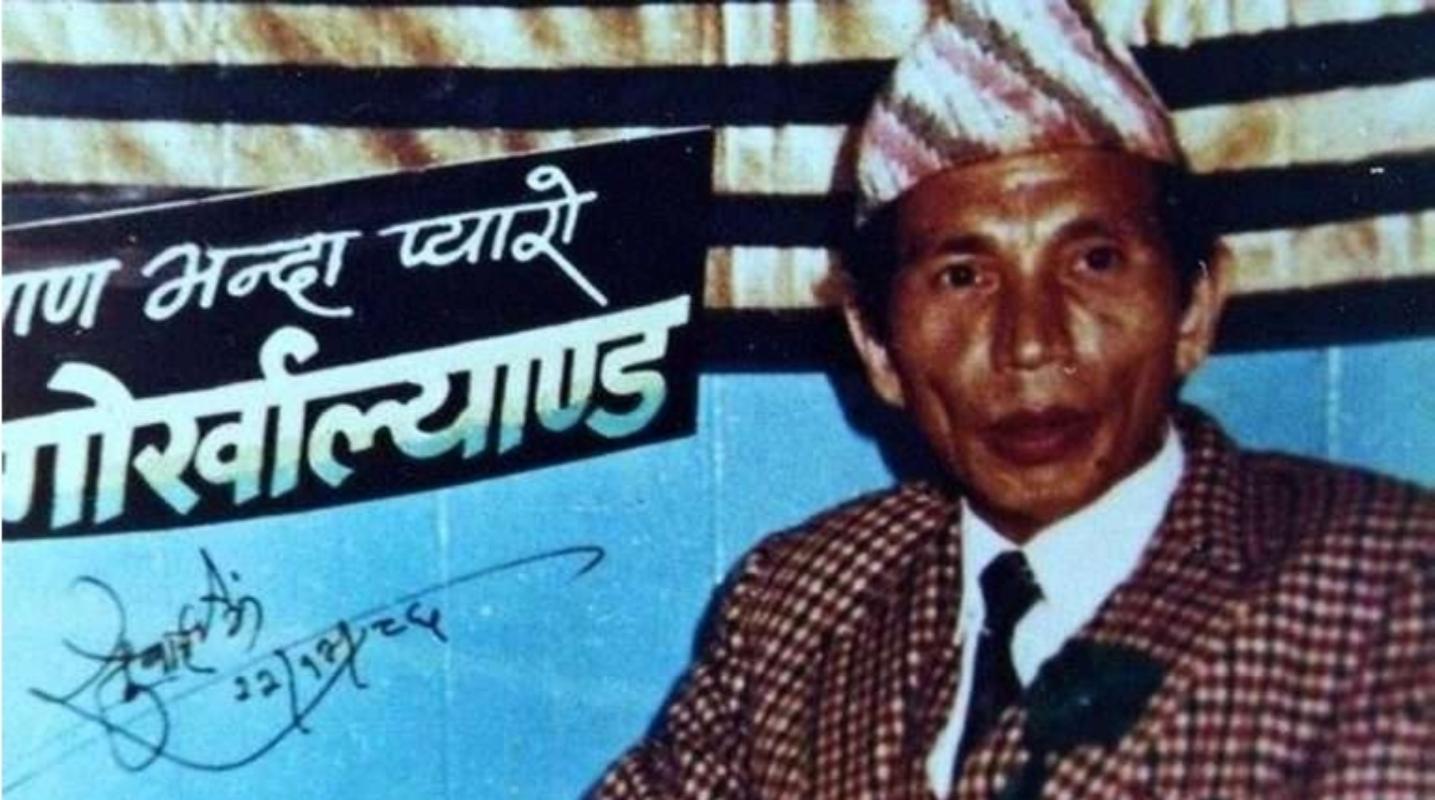

In Darjeeling, the agitation for a separate Gorkhaland was successfully brought to an end in 1988 with the setting up of a semi-autonomous Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council with Subhash Ghising of the Gorkha Liberation Front as its head.

In all these Accords it was Rajiv’s statesmanship in putting national interest ahead of the Congress party’s interest that enabled their successful conclusion. This was not popular within the Congress Party and probably contributed to the split in the Party in 1989 with the defection of Arun Nehru, Arif Mohammed Khan and some other Congressmen to the VP Singh camp.

Mani wonders whether Rajiv was being politically naïve in his approach but answers that Rajiv did not believe that the purpose of leadership must be to cling on to power at any cost. Rather, he saw his role as being above narrow, partisan interests and acting in the larger interest of the nation. Nor did Rajiv view dissidents as enemies, but as potential partners in nation building.

In J&K, the picture was more complex as the winding down of the conflict in Afghanistan with the easy availability of well trained and armed jehadis who could be diverted to Kashmir by Pakistan and missteps by Governor Jagmohan presaged turbulent times.

It had begun well with the conclusion of an alliance between Farooq Abdullah’s National Conference and the Rajiv Gandhi led Indian National Congress in November 1986. This was underpinned by a huge thrust to economic and infrastructure development in the State. The alliance won 64 seats in the Assembly in March 1987, while the opposition Muslim United Front won only 4 seats.

The election was, however, dogged by rumours of rigging. Mani cites Wajahat Habibullah, who was posted in J&K at that time, who has assessed that rigging may indeed have occurred in some 10 seats that were won by the National Conference, but this did not change the overall alliance victory. While there may have been discontent simmering in the Kashmir Valley, on the surface the situation was normal with the government firmly in control. Indeed, a record number of tourists visited J&K in the autumn of 1989.

The mishandling of the kidnapping, by Kashmiri extremists, of the Home Minister’s daughter under the VP Singh government and the reappointment of Jagmohan as Governor, despite his known prejudices, caused the situation to unravel. Farooq Abdullah resigned as Chief Minister over Jagmohan’s appointment. Jagmohan dissolved the State Assembly, possibly without even consulting the Central Government. The State plunged into a period of dark turmoil with Jagmohan’s efforts to delegitimise the National Conference and the Congress Party and promote the separatist JKLF.

The panic induced exodus of the Kashmiri Pandits, encouraged by Jagmohan, the strife torn years of terrorism which targeted people of all faiths followed. (Mani quotes a reply to an RTI query by the Deputy Superintendent of Police of Srinagar that “ since the inception of militancy in the 1990s “ the total number of Kashmiri Pandits killed is 89, compared to the killing of people of other faiths, mainly Muslim, which stands at 1,635). The communal colour sought to be given to the conflict is, as Mani puts it “ahistorical”. Mani, perhaps, underestimates the impact of Pakistan’s efforts to communalise the situation.

Panchayat Raj

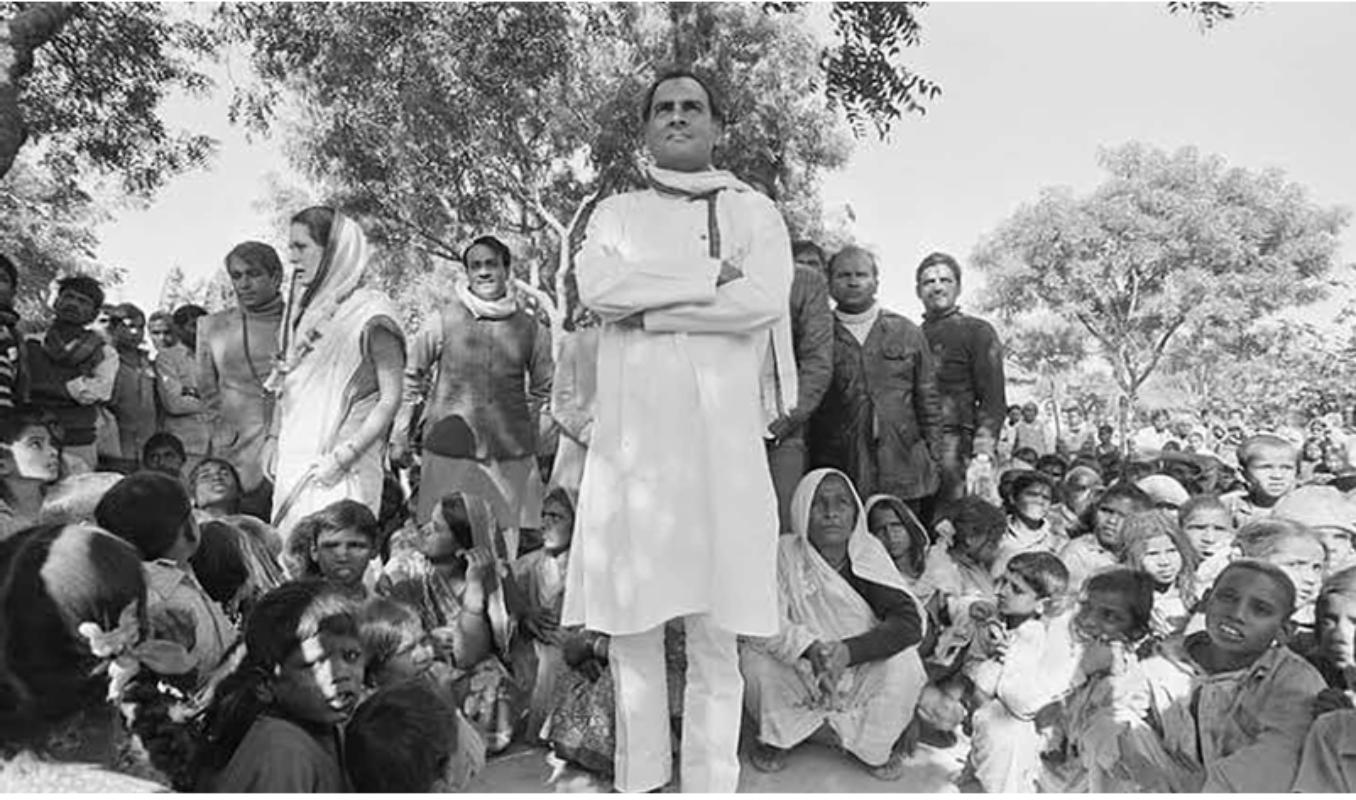

One of Rajiv’s signal achievements (and for Mani a personal crusade) and his most transformative contribution was the evolution of Panchayat Raj. Democracy to be meaningful has to be, essentially, local. However, our Constitution left a huge gap at the local level after the two tiers of governance at the Centre and the States.

Panchayat Raj was brought into the State List in November 1948 and included only in the non-binding Directive Principles of the Constitution. While Nehru eventually realised that without a democratic administration at the grass roots implementation of government plans would falter and prepared a model law to be passed by state legislatures in 1959, the initiative petered out after his death. In 1986 Rajiv introduced the idea of moving amendments to the Constitution and thereby giving Panchayat Raj Constitutional status.

Initially, Rajiv believed that better delivery of government programmes was a question of better management practices. Later, however, he was convinced that democratic empowerment at the grass roots was key to more responsible governance.

Mani details the exhaustive process of debate and consultation initiated by Rajiv Gandhi leading up to the 73rd amendments to the Constitution. To address concerns of “elite capture” of local bodies, novel provisions were incorporated for broad basing representation through reserving 33% of seats in the Panchayats and Municipal bodies for women.

This was a truly revolutionary move which empowered 1.4 million women to play a role in the democratic process. Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes would also be represented in proportion to their population. Tribal majority states, such as Nagaland, were exempted so that their own systems of tribal governance could continue.

The legislation provided for regular, timely elections to Panchayats through State Election Commissions, with devolved powers in respect of planning, economic development and social justice. Law and order would continue to vest in the District Magistrate. Similar provisions were made in respect of Municipal bodies, with some modifications.

The draft Bill was introduced by Rajiv Gandhi in the Lok Sabha on 15th May 1989, but the debate was clouded by the leakage of the CAG report on the acquisition of the Bofors gun with the opposition walking out. This made for easy passage in the Lok Sabha, but in the Rajya Sabha it fell short by a few votes.

Rajiv decided to make Panchayat Raj a key plank of his election platform. For Mani, personally, his passionate involvement with the evolution of Panchayat Raj was the trigger which prompted his resignation from the Indian Foreign Service and his embrace of a career in politics.

After Rajiv’s death, Mani continued his personal championing of Panchayat Raj till the passage of the Panchayat Raj Bill in 1992, a year after Rajiv’s assassination.

How successful has Panchayati Raj been? Mani underlines that we now have 260,000 democratically elected units of local self-government with some 3.2 million representatives. Almost 1.4 million of these are women, some 100,000 of whom are Chairpersons or Vice Chairpersons. About 650,000 lakhs are from the Scheduled Castes or Scheduled Tribes.

The Amendments have, therefore, truly revolutionised the broadening of democratic participation at the grass roots and ensured the unprecedented inclusion of marginalised groups. They have, however, been hobbled by the reluctance of State Governments to devolve financial resources and powers.

Safeguards to address concerns that Panchayat Raj does not become Sarpanch raj have also proved inadequate. Hopefully these weaknesses will be addressed by future governments so that inclusive, responsible and accountable democracy comes to inform local governance.

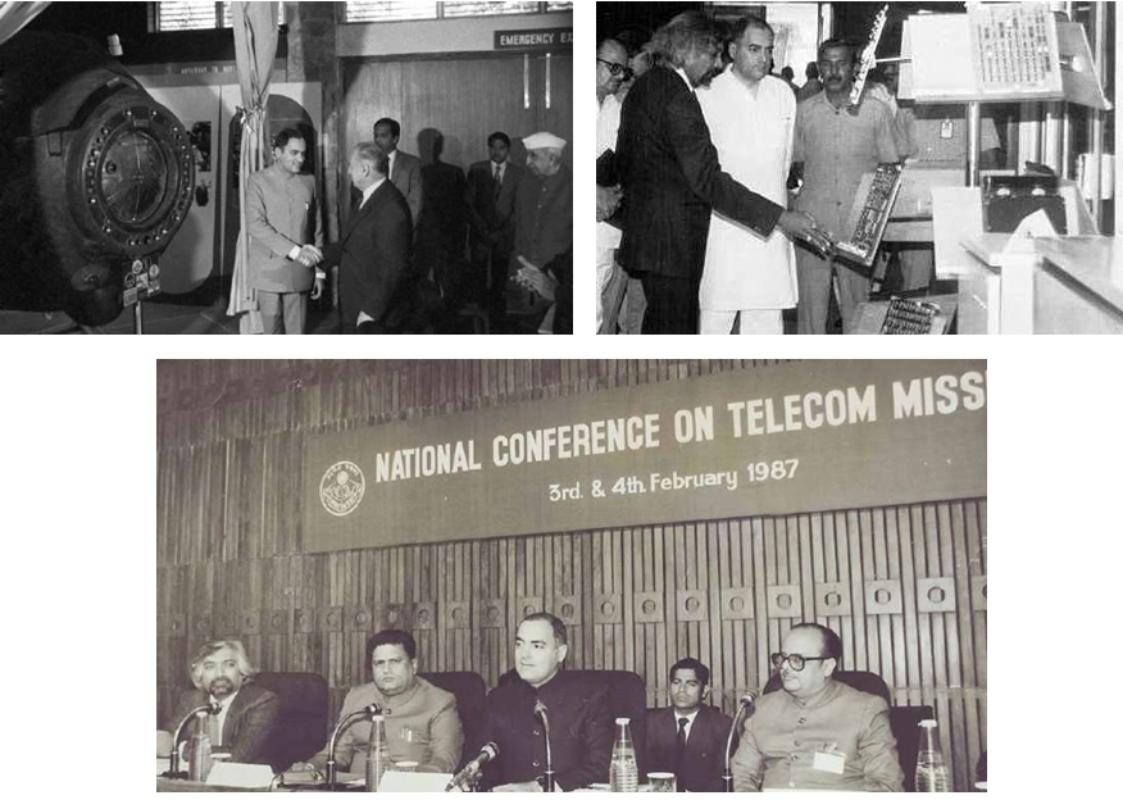

Technology Missions

Rajiv understood the importance of technology in the modern age. He believed that the focussed application of technology could help address many issues of India’s economic and social development.

His Technology Missions which sought to harness the power of technology for solving everyday problems of health, communication, safe drinking water and nutrition, were innovations at that time. Drinking water, immunisation, edible oils, the telecom network and dairy development were the focus of the Technology Missions, leading to major advances in some of these sectors, such as dairy development, immunisation and telecom. Others, such as the oil seeds Mission did not make the progress expected.

There were also S&T projects in Mission mode on a range of issues, including adult literacy, goitre control, weather forecasting, development of amorphous silicon solar cell technology, integrated vector control of vector borne diseases and rehabilitation of the handicapped. Rajiv’s emphasis on computerisation drew some media derision and I recall a cartoon showing a bullock cart which lampooned Rajiv for promoting “computers in the age of bullock carts!” It is Rajiv who has had the last laugh here, as information technology and software services have come to be key drivers of growth in the Indian economy. Of course, bullock carts have not vanished, though they have become much fewer. And this highlights the challenges which still remain for India’s development.

Foreign policy

In the field of Foreign Policy, two major initiatives stand out, breaking new ground with China and Pakistan. At the start of his term, Rajiv Gandhi had tasked Additional Secretary Gopi Arora and Parliamentary Secretary Arun Singh to take a fresh look at India’s relations with China. These efforts had been in the offing since Indira Gandhi’s re-election in 1980. In 1983, she had received an invitation from Deng Xiaoping to visit China.

The preparations for this visit were reset when Rajiv became Prime Minister. The thaw in the Soviet Union’s relations with China and the joint demarcation of the disputed boundary between the two countries added fresh impetus to our efforts. But the discovery of permanent structures built by China in the Sumdorong Chu Valley in 1986 brought fresh tensions. Rajiv approved a military riposte by our troops outflanking the Chinese and occupying the Hathungla Ridge.

He also conferred full statehood on Arunachal Pradesh in December 1986. The State was formally inaugurated in February 1987. A heavy build up of troops took place on both sides of the border as the snow thawed. However tensions eased with the visit of the Raksha Mantri and External Affairs Ministers in quick succession in April/ May 1987 to Beijing. By mid-1987 preparations for Rajiv’s visit were back on track.

With Pakistan, Rajiv made a concerted effort to improve ties, meeting with Zia-ul-Haq six times in his first year. While Mani maintains that Zia was sincere in seeking better ties with India, he underestimates that Pakistan’s transformation into a front-line state in the jehad against the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, its support to militancy in Punjab and J&K, and its clandestine efforts to acquire nuclear weapons adversely impacted Zia’s credibility and injected a note of caution in our dealings with Pakistan.

Rajiv visited Pakistan again the following year in July 1989. In the meanwhile back-channel discussions on Siachin had made progress but fell through as Rajiv was out of office within four months and Benazir was removed from office by the Army within two years.

Later, PM Narsimha Rao called off a potential agreement for mapping of ground positions, a mutual pull back of forces and establishment of a demilitarised zone, because of the political shadow of the Babri Masjid dispute.

Mani argues passionately for insulating India-Pakistan relations from domestic and electoral compulsions. But this is easier said than done. The most formidable obstacle remains Pakistan’s Army and Security establishment which would have to give up their policy of strategic overreach for stable ties with India.

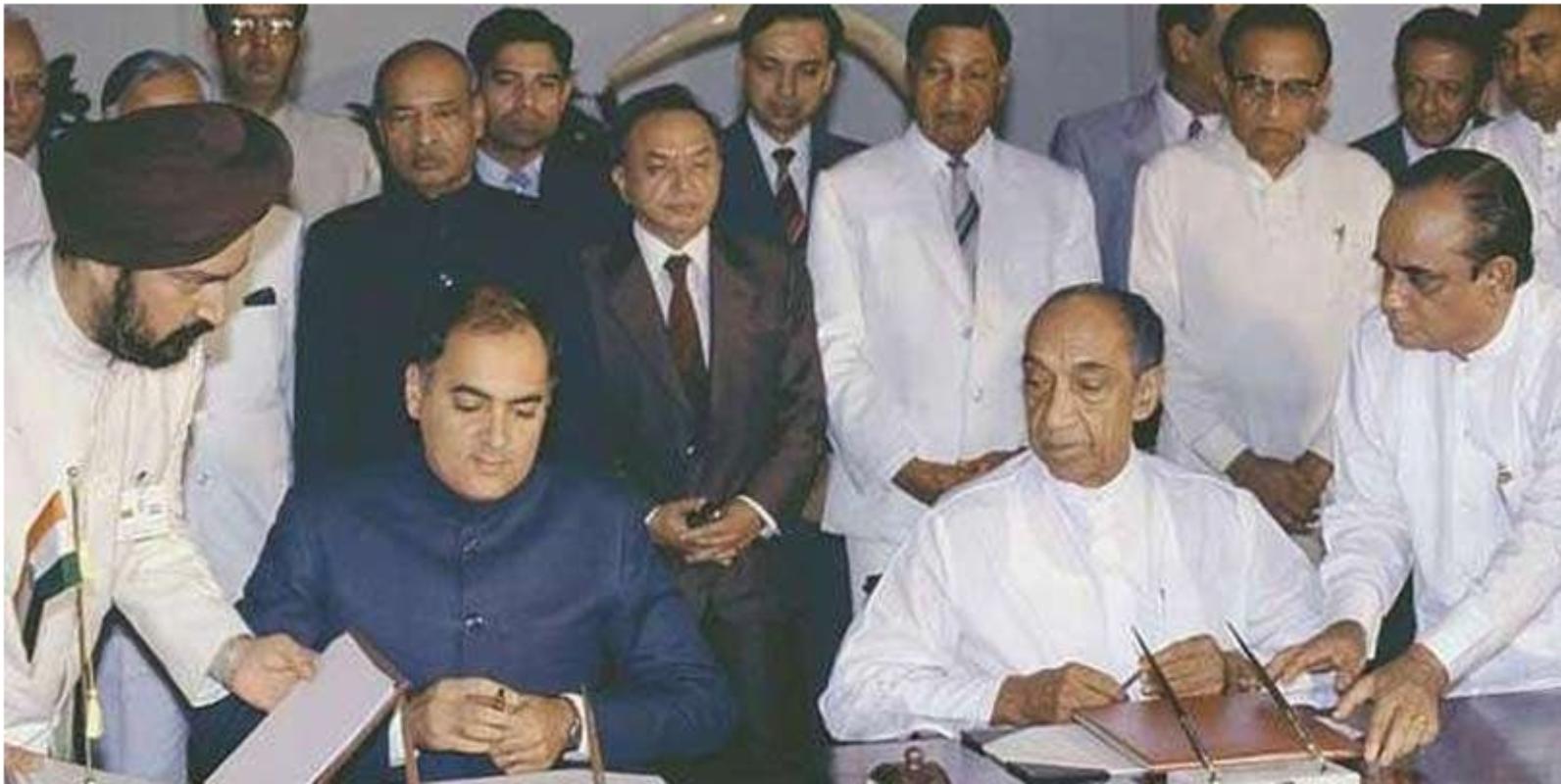

The Indo-Sri Lanka Accord of July 1987 was a sincere effort to find a political solution fair to both the Tamil and Sinhala communities in Sri Lanka.

However, the Accord soon unravelled on the intransigence of Prabhakaran and the LTTE on the one side, and Sinhala chauvinism on the other side which undermined the implementation of the agreement.

An Indian Peace Keeping Force was sent to Sri Lanka at the request of President Jayawardene, but it soon got sucked in to an active fighting role against the LTTE.

Rajiv paid with his life for listening to his advisors who,in my view, did not appreciate that military intervention in an open-ended situation, which did not lend itself to surgical action, would end in failure.

Unlike in Sri Lanka, the military intervention authorised by Rajiv in support of the Maldives government, which was facing a coup by disgruntled expatriate Maldivians, in November 1988 was swift, surgical and successful. Two IAF aircraft were despatched on 4th November 1988 with 300 paratroopers and completed their mission without any casualties.

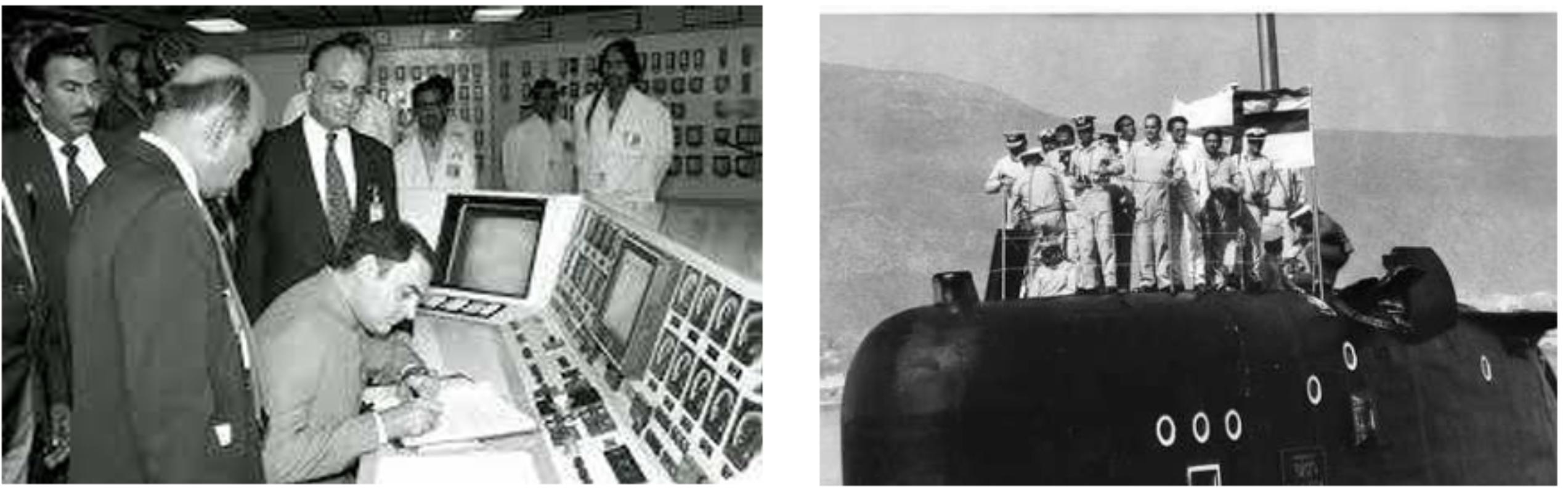

Going Nuclear

Rajiv was a staunch advocate of nuclear disarmament. When he was briefed on the infirmities of the Non-Proliferation Treaty which had divided the world into nuclear haves and have nots, and had allowed the nuclear weapon states to proliferate their nuclear arsenals manifold, he sought to know what a fair and acceptable Treaty might look like from our point of view.

This was the genesis of the Rajiv Gandhi Action Plan for a Nuclear Weapons Free and Non-Violent World. This provided for a phased and time bound elimination of nuclear weapons by the nuclear weapon states by 2010, with an equal and reciprocal commitment by the threshold and non-nuclear weapon states not to cross the nuclear threshold. The plan failed to find traction when it was presented to the Third UN Conference on Disarmament in June,1988.

Meanwhile advances by Pakistan towards nuclear weapons were forcing Rajiv’s hand. A Q Khan told Kuldip Nayyar in January 1987 in an interview in the midst of the Brasstacks crisis that Pakistan had the bomb. In March 1987 in an interview to Time magazine Zia said that” Pakistan has the capability to build the bomb whenever it wishes”.

After getting a detailed intelligence assessment Rajiv took the difficult decision for Department of Atomic Energy to secretly begin developing nuclear weapons. He did not take the decision to test. Perhaps, we were not fully ready for this at that time.

Economic policy

Mani does not touch at any length on Rajiv’s economic policy. He points out that Rajiv held to the socialist values of a more just and humane society but recognised the need for India to adapt in response to the changing situation. The gradual liberalisation during his term delivered the highest industrial growth rates since independence.

Rajiv was poised to pursue a more determined economic liberalisation had he won. Indeed, it is an irony that Narsimha Rao, the Prime Minister who ushered in economic reforms, was included in the Expert Group on economic policy set up by Rajiv in preparation for the 1991 General Elections, as a representative of the ‘old guard’ who had to be carried along. This spade work made it easier for Narsimha Rao to undertake the 1991 economic reforms.

Controversies

Rajiv’s term as Prime Minister was dogged by controversies. It began with a blood bath against the Sikh community in retaliation for the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi by her Sikh bodyguards.

The Home Ministry, headed by Narsimha Rao, and the Delhi Administration did little to stop the rioting. This will, forever, remain a stain on our record as a nation. After his mother’s funeral Rajiv took charge and the riots were brought under control.

Some, like Bofors, eventually petered out with no evidence emerging of any payoffs to Rajiv Gandhi or Defence Secretary Bhatnagar despite years of investigating. The Supreme Court finally put an end to the controversy with its judgement of 4 February,2004 in which Justice Kapoor held that no case had been made out despite thirteen years of investigation.

Mani makes a plausible argument, through circumstantial evidence, that the powerful Arun Nehru (MoS Home) had probably orchestrated the Bofors pay-offs behind Rajiv’s back and that is why subsequent opposition governments did not pursue the investigations seriously. The ultimate vindication of the purchase of the Bofors gun came in the Kargil conflict when its shoot and scoot capability was critical to India’s success.

Others, like the decision on Shah Bano and the subsequent decision to unlock the gates of the Babri Masjid have cast a long shadow on Indian politics, sharpening religious cleavages and pushing politics towards a majoritarian turn.

Mani, quoting Wajahat Habibullah, believes that Rajiv was not consulted when the decision to unlock the gates was taken and that it was, in all likelihood, engineered by Arun Nehru and led to his being dropped from the Cabinet in October 1986.

The subsequent efforts by Rajiv to find a negotiated settlement were soon overshadowed by the General Elections. While the original decision to unlock the Babri Masjid may or may not have been taken with Rajiv’s cognisance, he did agree to the subsequent Shilanyas. This alienated the Muslim community and was instrumental in Rajiv’s defeat at the hustings. Today, the Congress is still struggling to rebuild itself in the Hindi heartland.

As Prime Minister, Rajiv had little prior experience in the intrigues of Indian politics. Straight forward and confident by nature, Rajiv trusted his advisors to a fault. He did not understand how proximity to or the desire for power changes people and that leadership at the top is, essentially, a lonely place.

What he did strive for with the energy and impatience of youth, was to address India’s political cleavages, empower democracy at the grassroots and bring the force of technology to bear on solving problems of India’s economic and social development. His was a truly modernising impulse, preparing India for the twenty first century. Mani’s book is a must read for anyone seeking a fair assessment of someone who could have become one of India’s transformative leaders ,after a stint in the opposition, had he survived.