Wake Up Call on Health Care

The COVID pandemic starkly highlighted the inadequacy of government health care capacities and hospital beds in the country as well as the wide disparity among states.

Private health care facilities and hospitals have been growing rapidly and are getting better. But these are expensive and unaffordable for most Indians.

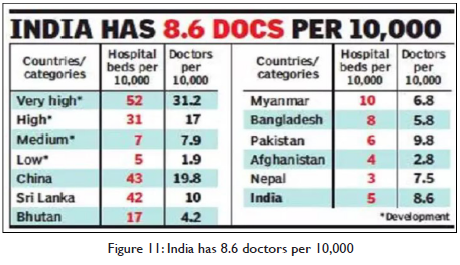

Bangladesh now has better health parameters of life expectancy and infant mortality than India. China is near the level of developed countries.

Way Forward

- Hospital Development. National Program for increasing hospital bed capacity to 1.5 per thousand in each district in five years may be launched. The Central government should fully fund the building and equipment costs of individual district projects with the condition that the state governments commit themselves to bearing the operating costs of staff and maintenance. Central government would need to provide about 5 lakh crores for this over five years. This is feasible.

- Full Holistic Free Public Health Care. Health Care is a fundamental right. India needs to move from the Insurance for procedures to full free lifetime holistic public health care for all. This would enable greater focus on preventive health care which is the key to better outcomes at lower costs. The CGHS model for central government servants in India and the NHS (National Health Service) model of the UK are good successful examples. For this government expenditure on health needs to be raised to 3% of GDP at the earliest. Health care should have the highest claim on the resources of the state. Resources may be augmented through a new health cess on Income and Corporate Taxes.

- Modernization. The use of digital technology offers great promise. It would increase efficiency and productivity. Quality of service especially in rural areas would be transformed. A Digital Health Technology Mission may be launched to facilitate a rapid transformation. The cost saving potential is also huge.

- Reform Private Health Care and Insurance. A competitive industry structure where service providers compete both on quality as well as costs has evolved. It needs to be nurtured to get a share of the global market. Private health insurers jointly with health care providers need to offer lifetime health care covering all costs. This needs to be introduced as a new health insurance product and should be mandated by the Regulator. This would be in addition to the present system of insurance for coverage of the cost of treatment and procedures subject to caps.

Introduction

The National Health Policy 2017 has as its goal “the attainment of the highest possible level of health and well-being for all at all ages through a preventive and promotive health care orientation in all developmental policies, and universal access to good quality health care services without anyone having to face financial hardship as a consequence” (Singh, 2017). The Covid pandemic, especially the vicious second wave this year, has starkly brought into focus the shortcomings on the provision of healthcare and the need to overcome these at the earliest.

In this paper we look at the existing state of health care in the country. Taking the current situation and capacities into account we suggest a feasible road map for achieving the goals of the National Health Policy, fully within this decade and substantially within five years.

State of Healthcare

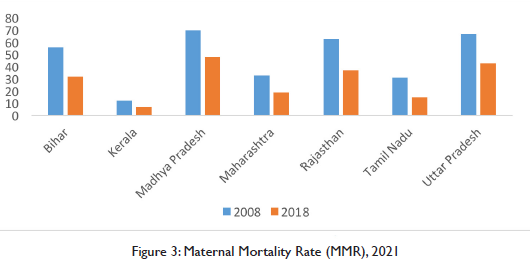

Health care has been a priority since independence. There have been major achievements in the key parameters of life expectancy, infant mortality, and maternal mortality. But there is still a significant gap between us and the developed countries. India’s immediate neighbour Bangladesh has done better. Sri Lanka and China have done far better.

| Table 1: Life Expectancy in years across countries2 | ||

| Country Name | 2000 | 2019-20 |

| Bangladesh | 65 | 73 |

| China | 71 | 77 |

| Sri Lanka | 71 | 77 |

| India | 62 | 70 |

| Japan | 81 | 84 |

| United Kingdom | 78 | 81 |

| United States | 77 | 79 |

| Table 2: Infant Mortality Rate3 across countries | ||

| Country Name | 1999 | 2019 |

| Bangladesh | 67 | 26 |

| China | 32 | 7 |

| Sri Lanka | 15 | 6 |

| India | 69 | 28 |

| Japan | 3 | 2 |

| United Kingdom | 6 | 4 |

| United States | 7 | 6 |

| Table 3: Maternal Mortality Rate4 across countries | ||

| Country Name | 2000 | 2017 |

| Bangladesh | 434 | 173 |

| China | 59 | 29 |

| Sri Lanka | 56 | 36 |

| India | 370 | 145 |

| Japan | 9 | 5 |

| United Kingdom | 10 | 7 |

| United States | 12 | 19 |

Healthcare across States

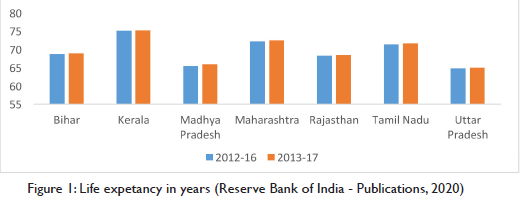

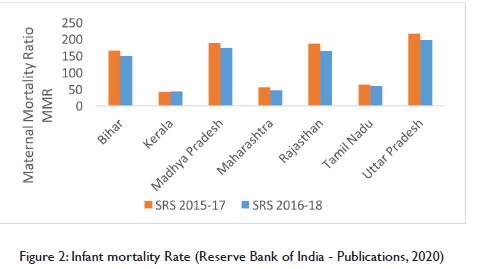

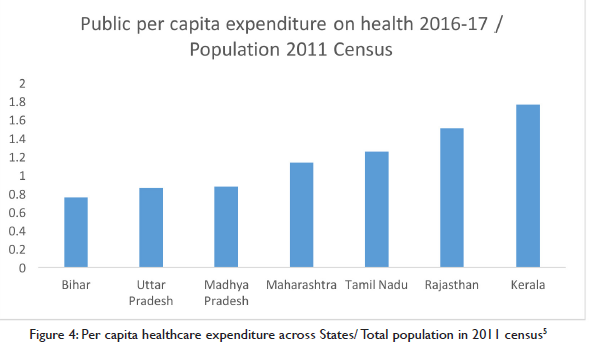

Health is a state subject under the Constitution. There is wide variation in key health parameters across states with Kerala at one end, being almost at par with developed economies, and UP at the other end having a lot of catching up to do.

Public Healthcare

The state, in keeping with the spirit of the Directive Principles in the Constitution and in response to the expectations of the people, has from the outset been endeavouring to provide medical treatment to all. In rural areas a network of Primary Health Care Centres (PHCs), one for each Block, were created. Now there is one community health worker, ASHA, in each village. There are district hospitals for treatment of most categories of ailments. Government run medical colleges have attached hospitals which provide the full range of specialised diagnosis and treatment. This network aimed at providing free treatment. As resources became an increasing constraint, the patient has to now buy more specialised medicines on his own though testing, diagnosis and surgical procedures remain practically free.

The quality of free public medical care varies sharply across states. At one end there is Kerala where health parameters have been comparable with those of the developed countries. At the other end are the large states of UP and Bihar where there is still a huge shortfall in public health care capacities. In some states, the confidence of ordinary people in the availability and quality of service from government facilities has been declining. They have, in increasing numbers, been choosing to opt for private treatment even though high private health care costs impose a strain and in cases needing major treatment the burden is unaffordable leading to impoverishment.

To address this problem and alleviate the distress among ordinary people in case of major illnesses, the central government has launched the ambitious national public health insurance program – Ayushman Bharat Pradhan Mantri Jan Arogya Yojana (AB PM-JAY) in 2018. It provides free access to health insurance coverage for low-income earners, the bottom 50%, in the country. It is a centrally sponsored scheme, jointly funded by both the union government and the states. The program is in its initial phase and would need to be scaled up rapidly with substantial increase in funding. The key features of the PM-JAY are the following:

- Providing health coverage for 10 crore households or 50 crore Indians.

- Providing a cover of Rs. 5 lakh per family per year for medical treatment in empanelled hospitals, both public and private (Sharma, 2019). All public facilities, from Community Health Centres to medical college hospitals would be automatically empanelled and private hospitals would be linked to specific service packages.

- It covers 3 days of pre-hospitalisation and 15 days of post-hospitalisation, including diagnostic care and expenses on medicines.

- The beneficiary can avail medical treatment at any PM-JAY empanelled hospital anywhere in the country (Sharma, 2019).

- The beneficiary gets free treatment. The hospital gets direct payment from the Insurance Fund

The central government allocation to Ayushman Bharat is Rs. 6400 crores for FY2020-21. The revised estimates for FY2019-20 were half (Rs. 3200 crore) of this (Kaur, 2020).

National Programs

India has successfully run national programs. These have been designed and financed by the central government and implemented by the states. These successes demonstrate state capacity to implement and deliver positive outcomes. The following are some examples.

The National Immunization programme was launched in 1978 which was renamed as Universal Immunization Programme (UIP). It is designed to cover all expecting mothers and infants in the country.. Under UIP, immunization is provided free of cost against 12 vaccine preventable diseases6. The two major milestones of UIP have been the elimination of polio in 2014 and maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination in 2015.

With Multi Drug Therapy (MDT), the National Leprosy Eradication Programme was introduced in 1983. India achieved the goal of elimination of leprosy as a public health problem, defined as less than 1 case per 10,000 population, at the national level in December 2005.

The Revised National TB Control Programme (RNTCP) (MoHFW, 2021) was launched in 1997 and full nation-wide coverage was achieved in March 2006. Under the programme, diagnosis and treatment facilities are provided free of cost to all TB patients. Treatment success rates tripled from 25% in pre-RNTCP era to 87% by 2014 and TB death rates have been reduced from 29% to 4% during the same period.

The Jeevan Suraksha Yojana (JSY) was started in 2005 to promote institutional deliveries. Communication and tracking of each pregnancy along with cash incentives for the expecting mothers from poor families and the ASHA worker have made a material difference. This is seen in the sharp decline in maternal mortality rates in recent years.

Full Healthcare for Employees

Health Care for Central Government Employees (Nagarajan, 2017)

The Armed Forces and the Railways had from the outset put in place an efficient full and free life-time medical treatment system for their employees with in-house doctors and hospitals.

The CGHS (Central Government Health Scheme) provides full life-time health care for Central Government employees. Approximately 38.5 lakh beneficiaries are covered by CGHS in 74 cities all over India. The government’s expenditure on CGHS was Rs. 2,300 crore which is approximately Rs.6,300 per beneficiary (2015 Data).

The CGHS has for some time been using the private sector through outsourcing to supplement in house capacity of CGHS doctors and government hospitals. It has settled rates for private consultation with specialists, testing and for treatments in empanelled diagnostic centres and hospitals. The patient does not have to pay to the service provider for consultation, tests, or treatment. She is also free to choose from among those authorised to provide services on getting a referral from the CGHS.

Health Care for Organised Sector Workers

India adopted the international practice of a contributory system of social security, including health care, for industrial workers. A network of health care facilities came up to provide medical treatment to workers covered under contributory health insurance. The growth of the organised industrial sector and its workers has been modest in India. Around 10% of workers are in the organised sector and have the benefit of free medical treatment. This system is also not seen by its beneficiaries very positively.

The practice in large firms and public sector undertakings on health care for their employees from private doctors and hospitals varies. It ranges from full cost reimbursement at one end to the other where the employee is paid well and is expected to meet his healthcare costs on his own and by taking health insurance.

Private Health Care

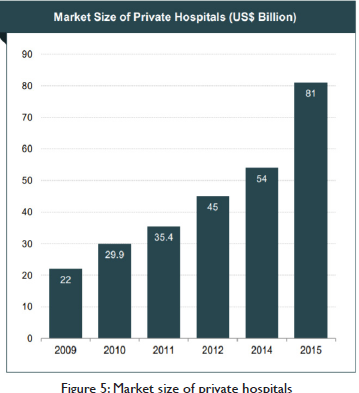

Market based private medical services have been growing rapidly, especially in the last few decades. The industry leaders are globally competitive in terms of the latest technologies of diagnosis and treatment and at costs far lower than that of their peers in the US. The phrase “medical tourism” has gained currency. This service industry has the potential of having a significant presence in the global market.

Nearly 58% of the hospitals in the country with 29% of beds and 81% of doctors are now in the private sector. According to National Family Health Survey-3, the private medical sector is the primary basis of health care for 70% of families in urban areas and 63% of families in rural areas (AIHMS Blog, 2020).

Large investments by private sector players are driving the growth of India’s hospital industry. During 2009–15, the market size of private hospitals is estimated to have had a CAGR of 24.2 per cent. Increase in number of hospitals in Tier-II and Tier-III cities has further fuelled growth. (IBEF, 2018).

Health Insurance

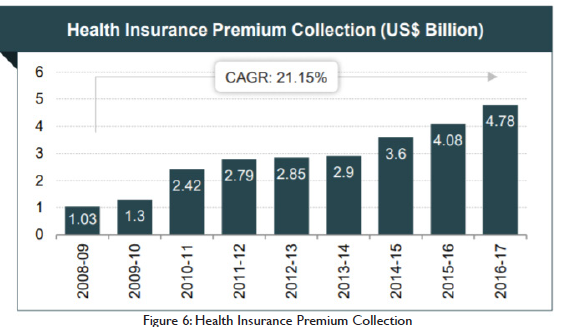

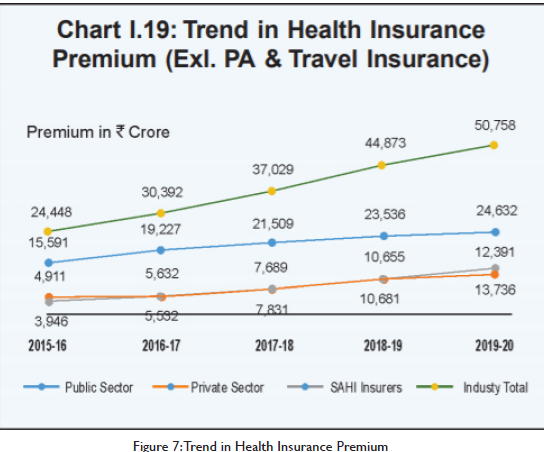

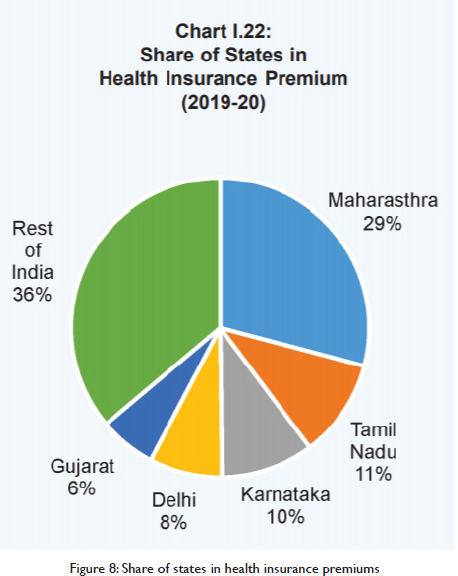

Health Insurance has grown to take care of the growing market need for insurance for expensive treatments. Health insurance premiums increased at a CAGR of 21.15 per cent between 2008–09 and 2016-17 (IBEF, 2018).

A competitive industry structure has emerged. Currently, there are 30 insurance companies in India that offer health insurance products. Out of these, 25 are general insurance companies and 5 are standalone health insurance companies. The Health Insurance industry is regulated by the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI).

A health insurance policy provides for reimbursement of cost of treatment for ailments covered under the policy subject to a maximum in a year. With higher insurance premia, the ceiling on reimbursement becomes higher. In the present system of full reimbursement, the hospital providing treatment has no incentives to control or lower the cost of treatment. There are higher returns for the health care provider if costs rise. These in turn result in insurance premia going up with higher returns for the insurer. Both gain by being on an escalating cost curve.

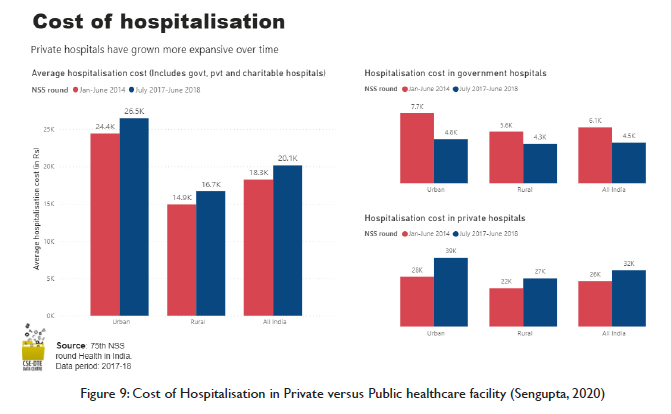

While private health care is improving in quality, it is also becoming more expensive. The following illustrates this:

- Hospitalisation for any ailment in a private hospital costs nearly 7 times more than in a government hospital. A one day stay in ICU (Intensive Care Unit) in Bangalore at government facility costs Rs. 1,500 while in a private hospital it is around Rs. 30,000 (Times of India).

- The cost of Covid care in a private hospital is about Rs 2 lakh for a mild to moderate case for one week and up to Rs 5-6 lakh for a severe infection (Punj, 2021).

Major Challenges

- Shortage of government hospitals and treatment facilities, acute in less developed states and districts.

- Declining faith in public health care among the people of many states.

- Weak preventive health care.

- Slow Modernisation.

- Rising and unaffordable private health care costs.

We need action on all these immediately through a comprehensive and holistic set of policies and programmes.

Hospital Capacity Development

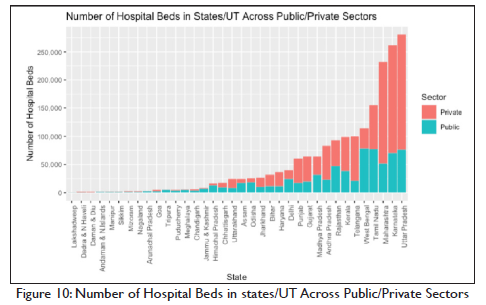

The COVID-19 crisis has driven home sharply the inadequacy of hospital bed and care capacity in the country. India has only 0.53 beds available per 1,000 people. There is also huge disparity among states and districts. Only the metros are well provided.

The shortage of hospital beds and related facilities in less developed districts is acute. So is the shortage of doctors, para medical staff and equipment in these districts.

A national program to raise health care infrastructure in the country to a minimum level is an immediate necessity. This needs to be funded by the central as well as state governments. A major pillar of this should be the provision of the minimum number of hospital beds in each district.

The Central government should provide full funding for construction and equipment for district wise projects and the State government should accept the responsibility of providing staff and meeting operational costs of these district wise projects. The state governments should have flexibility in managing these by themselves fully as well as with varying degrees of private partnerships.

India currently has about 5 beds available per 10,000 people which is total 6,76,300 beds. To achieve at least 1 bed per 1000, the country needs to fulfil the unmet demand of around 6,76,300 beds. This would require an investment of Rs. 2,47,977 crores. To achieve a level of 1.5 beds per 1000, the country needs to fulfil the unmet demand of around 13,52,600 beds requiring an investment of Rs. 4,95,953 crores over a period of 5 years. Commitment of this level of expenditure is feasible. This should get the highest priority in the Infrastructure Pipeline investment.

Augmenting Human Resources

A crash program for recruiting and training para medical personnel needs to be started now to see that as hospital beds get created, they are not understaffed. In our view an altogether different approach should be tried. Direct recruitment for para medical positions in individual hospitals at specific locations may be undertaken on contract. Training for skill and certification may be undertaken after recruitment and the employee may be given a modest student stipend for personnel expenses. He may be provided board and lodging in the training facility.

The educational qualification needed for admission to a para medical training institution should be the eligibility criterion for such recruitment. The contract should be for, say, seven years after training with the condition that if the employee leaves earlier she would pay the government the full cost of her training and a penalty. After successful completion of training and certification, the para medic would get her full salary. This would be somewhat similar to what the Armed Forces do. To the extent local youth get recruited and trained there would be greater probability of their staying and serving for longer periods. Recruitment on contract for a particular hospital or a rural health care facility would insulate the system from political and other kinds of mobilisation for a shift from a backward district to a better place.

Getting doctors would need a slight variation in this approach, Campus visits and recruitment may be undertaken among students in, say, the second or third year, on similar conditions of their educational expenses including board and lodging being fully funded on recruitment. They may be given the added incentive that if their performance during the contractual period is good, they would join the state medical cadre at an appropriate level and seniority. This would be a reward for serving in a remote place.

The central government while financing the construction of hospital beds and related equipment can get the commitment of the state governments on milestones for creation of posts and recruitment to ensure that when the hospital beds are ready, and equipment has been installed the staff is also in position.

Preventive Health Care

It is now axiomatic that preventive health care should get the highest priority. It costs the least and the returns are very high. But surprisingly preventive health care gets emphasised in policy documents but does not get the requisite priority when it comes to programs and outlays.

There are many low hanging fruits in preventive health care. Part of the problem lies in the absence of a holistic system of analysis of the different dimensions of preventive health care, their costs and benefits, and pathways to desired outcomes. The canvas of preventive health care in India is quite wide. Many are what economists call “public goods” and only government action can be effective.

There are public goods which effect health and impose huge and avoidable costs on large sections of the population. The most critical in North India is air pollution. Air pollution levels are estimated to be shortening lives in Delhi by 9.4 years. Air can be made clean in five years. This is affordable. This needs to get priority and coordinated action with adequate resources.

Malaria, dengue, and encephalitis are endemic. Better management of drainage and wastewater could free us of these. The health benefits would far outweigh the costs. Malaria has been eliminated from Sri Lanka.

Putting industrial waste with toxic chemicals as municipal waste is another health hazard. They evaporate and pollute the air in the below 2.5PM range and many are carcinogenic. The public cost of collecting and treating this waste separately is far lower than the health care costs this imposes on society.

Then there are free preventive health care practices which only need communication and changes in lifestyles and where the health benefits and cost savings are huge. Mass communication in all our regional languages and dialects through the enhanced power of social media and the internet is a low-cost powerful instrument.

To illustrate, the diabetes epidemic could be arrested and reversed with changes in diet by reducing sugar, and Maida based processed food consumption and returning to regional traditional foods. Then there are regional affordable foods which can be popularised to reduce the widespread prevalence of anaemia in women.

Modernisation and Cost Reduction

The new digital age offers enormous possibilities of increasing the efficiency of delivery of total health care as well as its costs. India can leapfrog. It has taken a pioneering initiative with E-Sanjeevani7. A full-fledged Digital Health Technology Mission is needed. Some possibilities are indicated below.

Creation of guidelines in all our regional languages which, say, adapt the National Health Service (NHS) guidelines of UK. These are comprehensive, user friendly and cover the entire spectrum. These would be of great value to all. There would need to be a system of continuous updating.

SOPs (Standard Operating Procedures) for doctors modelled on the NHS pattern would help. A system of seeking guidance digitally in more difficult cases from specialists higher up in the hierarchy would obviate the need in many cases for the patient travelling to the state capital for diagnosis.

Surgery and other medical procedures can be more efficiently scheduled. Reference to super speciality hospitals would come down to very difficult and complicated cases.

SOP effectiveness and compliance can be audited with digital record keeping. Human audit would evolve into appropriate data analytics. Audit should reduce inappropriate but widespread prescription of antibiotics. This would need to be supported by mass communication so that patients do not needlessly expect and demand antibiotics.

Tele consulting and prescription has emerged during the Covid lockdown. E-Sanjeevni has been a good beginning. The states could introduce this and scale it up. It would be a great boon for rural and remote areas.

Digital health record keeping is emerging. It can be extended to cover all. It’s benefits in better and speedy diagnosis are well recognised. Privacy should be adequately safeguarded

Para medical and nursing staff can be guided remotely through digital communication in giving patients better care. They can also be given greater responsibilities.

The need for stay in hospitals can be minimised with the development of homecare capacities with the guidance of doctors, visits by paramedical staff and training of family members. Out of necessity a good beginning was made for Covid patients recently. In terminal cases supervised homecare is psychologically better both for the patient and the family. This would reduce the requirements of hospital bed capacity as well as costs.

Universal Free Public Health Care

The fundamental transition that is now needed is provision by the state governments of free and full lifetime public health care including the cost of medicines.

The NHS is a good model to emulate. It provides free lifetime health care to all. It is cost effective. UK’s expenditure on health care as a percentage of GDP is among the lowest. It is only 9.5% of GDP for health outcomes which are comparable to those of the US which spends 17.5% of GDP on health care.

The full free care system of the central government for its employees through the CGHS provides a useful template for use by the state governments.

Those with higher incomes may continue to use private health care. They have the freedom to choose in the market for supply of private health care.

From the present 1.26% of GDP expenditure on public health care, an additional 1% of GDP, may be provided in the next two years. This may be raised to 3% of GDP at the earliest. Only such a quantum increase would lead to a qualitative transformation and a time bound movement to full free health care for all. Going forward expenditures would need to rise further.

The right to health is a fundamental right. Budgetary resources would have to be found for it and should get the highest priority. A health care cess on personal and corporate incomes to generate additional resources should be imposed. It would be amply justified. . On the other hand, it is neither reasonable nor fair to ask the poor to pay for health care.

The cost implications of full free care can be seen by extrapolating the cost of about Rs 6,000 being incurred per year for each CGHS beneficiary to 80% of the population of the country. The total would be approximately 6 lakh crore per year. It is likely that in implementation actual costs would be lower if at the same time preventive health care and other cost reduction ideas being suggested are implemented.

Over the medium term, full care with timely preventive measures through lifestyle changes, early detection and treatment should result in lowering overall costs compared to a system which provides only insurance-based cover for treatment of specified diseases and procedures.

The national ambition should be to achieve effective universal free public health care in the next 5 to 7 years. The Indian state must deliver on this fundamental human right within this decade to comply with the SDG (Sustainable Development Goals). The economic returns from higher productivity of a healthy population would also be very high. This would naturally facilitate the achievement of higher growth rates.

Private Health Care Reform

Private provision of health care has been growing rapidly. A competitive industry structure has emerged in response to market demand. At one end the metropolitan centres have world class super speciality hospitals which are globally competitive in quality and price. Private hospitals, diagnostic centres, and maternity nursing homes are all increasing in numbers in other cities. The inadequacy of government facilities combined with the public perception about the indifferent quality of service has fuelled increase in demand for private facilities.

This is a free and competitive market with service providers at different price and quality points. But once the initial choice is made, the patient (consumer) begins to face a virtual monopoly situation as he would usually stay with his hospital and doctors (the service provider) and his demand becomes inelastic. Even in terminal cases the patient usually continues in hospital, in its ICU and a ventilator, at great cost. This characteristic was highlighted starkly during the recent Corona pandemic where so many relatively better off families have not only lost some one dear to them but have also been considerably impoverished.

Taking a broader perspective, health care costs in a society decline as preventive health care improves. At the same time people live longer and health care costs rise for the elderly.

One reasonable view would be to let market forces alone. India could evolve into a global hub for medical treatment. To the extent India succeeds in becoming a cost-effective attractive destination for high quality treatment, we would be creating jobs and incomes. With an ageing population in the advanced countries the demand potential is enormous. This sector could grow as a sun rise services sector, as software was a generation earlier. For this to be facilitated, the industry on its own as well as at the behest of the Regulator needs to move towards creating greater transparency in its fees structure along with an Ombudsman system for consumer grievance redressal. Going forward the emergence of a credible star rating system which consumers could trust would be a good development for the industry.

There is also the need for reorientation towards cost control, getting desirable outcomes at lower costs. This is something that regulatory and policy instruments should attempt. Such a shift would not be easy as the present incentives do not favour controlling costs. The more the number of tests and surgical interventions with full reimbursement by insurance companies, the greater the returns for the service providers. In turn the insurance companies can charge higher premiums with higher reimbursement caps. This becomes a mutually reinforcing trajectory of higher costs. The turnover and profits for both, the health care service providers and the insurance companies grow in tandem.

Weaning away the system from prevailing high costs to lower costs without any negative impact on outcomes is something easy to prescribe but bound to be challenging when specifics are being worked out. The transition is not going to be easy. Competition amongst multiple insurers and service providers would be desirable.

Cost control would be a management concern only if the insurance cover was for full health care, including consultations, tests, medicines, and treatment for life, rather than for reimbursement for treatments with a cap. Once full insurance is provided,, competing insurers would tie up with competing health care providers encompassing the full-service delivery chain; the primary GP (General Physician) who with timely advice on lifestyle and dietary changes and early detection of problems would reduce the numbers who would need specialised diagnosis and treatment, to the specialists and hospitals to whom patients would go for treatment and surgical interventions.

With medicines being fully covered under insurance, the needless prescription of antibiotics and expensive drugs would hopefully come down. The use of cheaper generics would increase. The percentage of Caesarean births and hysterectomies among better off families would decline. These are far too high in India at present. At the other end of the spectrum the

practice of routinely putting terminally ill patients in their last days in the ICU with ventilators for many days would decline. In a competitive market, reputations would emerge regarding quality and price. Consumers should get a choice in the market of both, insurance with caps as well as a new market for insurance for full coverage.

The regulator and government after stakeholder consultations could fine tune the incentives for such a transition. The instruments used elsewhere suggest themselves. A higher tax break for a customer who buys comprehensive insurance could be one way of nurturing the emergence of this market. The Regulator may mandate that the Insurance Companies must begin providing this new product of comprehensive full health care, say, within three years.

Conclusion

India needs to give the highest priority to taking public health provision for its people to the next level and achieve health outcome parameters comparable to those of the developed countries by the end of this decade. Public expenditure on health care needs to rise to approximately 3.5% of GDP per year. This is essential and should get the highest priority.

Holistic health care with emphasis on prevention and cost-effective treatment would result in lower per capita costs with better outcomes. Preventive health care including lifestyle and dietary changes need greater priority. The use of digital technology offers great promise in improving efficiency as well as in reducing costs.

The emerging silos between primary and preventive care on the one hand and insurance-based reimbursement for treatments in hospitals needs to be reversed. Every citizen should get free life-time health care as a right. Those whose incomes are large enough to pay Income Tax, should pay a cess for health care. Similarly, firms should also pay a cess for health care over and above the taxes on their profits.

Those who have the resources to use private health care should continue to have the full freedom to choose in the market from competing suppliers of health care. The health care industry has been growing rapidly and is globally competitive. It should be supported in getting a rising share in the global market.

The health care industry and its related insurance industry need to be incentivised to jointly provide full lifetime health care, without any linkage to procedures or caps on treatment for an ailment or for a procedure. The emergence of a competitive industry structure for full free lifetime health care to be provided through insurance policies with monthly payments is a desirable and necessary transition. The present full reimbursement system with caps incentivises higher costs and not cost control.

References

AIHMS Blog | Explore Public Health. 2020. The Growth of Healthcare and Hospital System in India | AIHMS Blog. [online] Available at: https://aihms.in/blog/the-growth-of-healthcare-and-hospital-system-in-india/ [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Dghs.gov.in. 2021. NATIONAL LEPROSY ERADICATION PROGRAMME – DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF HEALTH SERVICES, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. [online] Available at: https://dghs.gov.in/content/1349_3_NationalLeprosyEradicationProgramme.aspx [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Dghs.gov.in. 2021. Revised National Tuberculosis Control Programme – DIRECTORATE GENERAL OF HEALTH SERVICES, Ministry of Health & Family Welfare, Government of India. [online] Available at: https://dghs.gov.in/content/1358_3_RevisedNationalTuberculosisControlProgramme.aspx [Accessed 14 September 2021].

IBEF.org. 2018. Healthcare – India Brand Equity Foundation (IBEF). [online] Available at: https://www.ibef.org/download/Healthcare-February-2018.pdf [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Kaur, B., 2020. Union Budget 2020-21: No increase in Ayushman Bharat allocations. [online] DowntoEarth. Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/health/union-budget-2020-21-no-increase-in-ayushman-bharat-allocations-69092 [Accessed 14 September 2021].

M.rbi.org.in. 2020. Reserve Bank of India – Publications. [online] Available at: https://m.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=20000 [Accessed 14 September 2021].

M.rbi.org.in. 2020. Reserve Bank of India – Publications. [online] Available at: https://m.rbi.org.in/Scripts/PublicationsView.aspx?id=19999 [Accessed 14 September 2021].

N.A., 2018. PM unveils Ayushman Bharat; 50 cr to get health cover of Rs. 5 lakh – The Hindu BusinessLine. [online] www.thehindubusinessline.com . Available at: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/news/national/pm-unveils-ayushman-bharat-50-cr-to-get-health-cover-of-5-lakh/article25022030.ece [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Pib.gov.in. 2021. Maternal Mortality Rate (MMR). [online] Available at: https://www.pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1697441 [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Punj, S., 2021. The financial burden of Covid care. [online] India Today. Available at: https://www.indiatoday.in/india-today-insight/story/the-financial-burden-of-covid-care-1817504-2021-06-21 [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Rao, S., 2020. Hospitalisation is 6 times more expensive in private sector: Study. [online] Time of India. Available at: http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/73052991.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Sengupta, R., 2020. Private hospitals grow more expensive even as insurance coverage remain low: NSSO. [online] DowntoEarth. Available at: https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/health/private-hospitals-grow-more-expensive-even-as-insurance-coverage-remain-low-nsso-72434 [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Shankar, A. & Tiwari, C., 2020. A Plan to Accelerate Recovery. [online] Centre for Policy Studies, JKLU. Available at: https://www.jklu.edu.in/wp-content/themes/jklu/images/centre-policy-studies.pdf [Accessed 14 September 2021].

Footnotes:

1 Ajay Shankar, Distinguished Fellow and Chairman, Centre for Policy Studies at JK Lakshmipat University (JKLU) and Chitranjali Tiwari, Policy Researcher Centre for Policy Studies at JK Lakshmipat University (JKLU) is an independent think-tank established with the vision of providing thought leadership and excellence to inform policymaking in India. The Centre aims to promote dialogue, conduct research, develop, and publish actionable ideas on critical policy issues. It hosts scholars, researchers and thought leaders round the year in addition to organising roundtables and events. The Centre is led by Mr. Ajay Shankar, former Secretary to Government of India, who serves as Chairman and Distinguished Fellow. For information, contact policycentre@jklu.edu.in

2 The World Bank Data – https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/

3. The infant mortality rate is the number of infant deaths for every 1,000 live births.

4. MMR is the number of maternal deaths per live birth. Defined by the WHO as the death of a woman from pregnancy-related causes during pregnancy or within 42 days of pregnancy, as a ratio to 100,000 live births

5. Calculated using Public Expenditure in Health 2016-17 (Rs. in 000) and 2011 census (population)

6. Nationally against 9 diseases – Diphtheria, Pertussis, Tetanus, Polio, Measles, Rubella, severe form of Childhood Tuberculosis, Hepatitis B and Meningitis & Pneumonia caused by Hemophilus Influenza type B. Sub-nationally against 3 diseases – Rotavirus diarrhoea, Pneumococcal Pneumonia and Japanese Encephalitis; of which Rotavirus vaccine and Pneumococcal Conjugate vaccine are in process of expansion while JE vaccine is provided only in endemic districts.

7. National TeleConsultation Services – https://esanjeevaniopd.in/