What is an Alternative?

Alternatives can be practical activities, policies, processes, technologies, and concepts/frameworks, practiced or proposed/propagated by any collective or individual. They can be continuations from the past, re-asserted in or modified for current times, or new ones; it is important to note that the term does not imply these are always ‘marginal’ or new, but rather that they stand in contrast to the mainstream or dominant system.

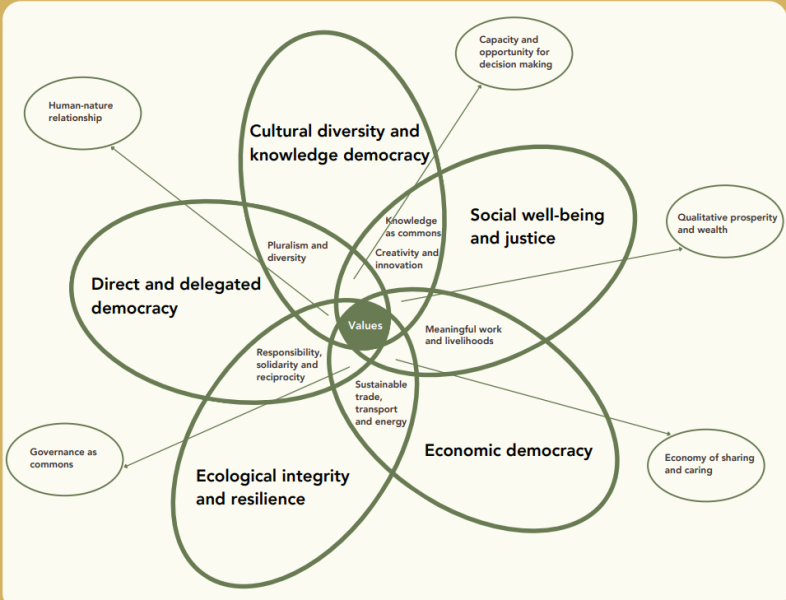

It is proposed that alternatives are built on the following inter-related, interlocking spheres, seen as an integrated whole:

- Ecological integrity and resilience, which includes maintaining the eco-regenerative processes that conserve ecosystems, species, functions, cycles, respect for ecological limits at various levels (local to global), and an ecological ethic in all human endeavour.

- Social well-being and justice, including lives that are fulfilling and satisfactory from physical, social, cultural, and spiritual perspectives; where there is equity between communities and individuals in socio-economic and political entitlements, benefits, rights and responsibilities; where there is communal and ethnic harmony; where hierarchies and divisions based on faith, gender, caste, class, ethnicity, ability, and other attributes are replaced by non-exploitative, non-oppressive, non-hierarchical, and non-discriminatory relations.

- Direct and delegated democracy, where decision-making starts at the smallest unit of human settlement, in which every human has the right, capacity and opportunity to take part, and builds up from this unit to larger levels of governance by delegates that are downwardly accountable to the units of direct democracy; and where decision-making is not simply on a ‘one-person one-vote’ basis but rather is consensual, while being respectful and supportive of the needs and rights of those currently marginalised (e.g. some minority groups).

- Economic democracy, in which local communities and individuals (including producers and consumers, wherever possible combined into one as ‘prosumers’) have control over the means of production, distribution, and exchange (including markets); where localization is a key principle, and larger trade and exchange is built on it on the principle of equal exchange; where private property gives way to the commons, removing the distinction between owner and worker.

- Cultural diversity and knowledge democracy, in which pluralism of ways of living, ideas and ideologies is respected, where creativity and innovation are encouraged, and where the generation, transmission and use of knowledge (traditional/modern, including science and technology) are accessible to all.

A crucial outcome of such an approach is that the centre of human activity is neither the state nor the corporation, but the community: a self-defined collection of people with some strong common and cohesive social interest. The community could be of various forms, from the ancient village to the urban neighbourhood to the student body of an institution to even the more ‘virtual’ networks of common interest. It is acknowledged here that the ‘community’ as traditionally conceived is not homogenous, and may contain levels of hierarchy, exploitation, and marginalisation; it would therefore be important to consider the sphere of social justice as being crucial in such situations.

Many or most current initiatives may not fulfil all the five spheres discussed above. Perhaps we can consider something an alternative if it addresses at least two of the above spheres (i.e. is actually helping to achieve them, or is explicitly or implicitly oriented towards them), and is not violative of other spheres but rather is open to them and their possible adoption. This means, for instance, that a producer company that achieves economic democracy but is ecologically unsustainable (and does not care about this), and is inequitable in governance and distribution of benefits (and does not care about this), may not be considered as an alternative. Similarly a brilliant technology that cuts down power consumption, but is affordable only by the ultra-rich, would not qualify (though it may still be worth considering if it has potential to be transformed into a technology for the poor as well).

What are the Alternatives in Various Sectors?

The Framework provides indicators of the kinds of initiatives that could be called alternatives, in 12 sectors or fields. To these are added actual examples of initiatives, mostly taken from the Vikalp Sangam website

Society, Culture and Peace

This includes initiatives to enhance social and cultural aspects of human life, such as sustaining India’s enormous language, art and crafts diversity, removing inequalities of caste, class, gender, ethnicity, literacy, race, religion, and location (rural-urban, near-remote), creating harmony amongst communities of different ethnicities, faiths and cultures, providing dignity in living for those currently oppressed, exploited, or marginalised, including the ‘disabled’ or differently abled and sexual minorities, promoting ethical living and thinking, and providing avenues for spiritual enlightenment.

Several examples come to mind. The work of Bhasha in documenting and sustaining language diversity across India while including related economic, political, cultural and social aspects, includes the People’s Linguistic Survey of India which documented 780 languages. The initiative of Landesa, a Seattle based non-profit, helps educate young women in West Bengal about their right to inherit property along with their brothers and teach them the hands-on skill necessary to be food secure.

To promote preservation of local/ traditional food, Kalpavriksh facilitates women’s self-help groups to organise ‘Wild Food Festivals’ in Bhimashankar (Maharashtra) to help the local adivasis revive traditional knowledge of their food and imbibe a sense of respect for local cuisine in an atmosphere of junk food invasion. Other examples mentioned below also deal with sustaining crafts as a livelihood and tackling gender and caste inequities through sustainable agriculture.

The Framework points to a caution that is important in the current context of an increasingly rightwing agenda supported by the state: that initiatives which appear to be alternative in one dimension, e.g. conservation, or sustaining appropriate traditions against the onslaught of wholesale modernity, would not be considered so if they have casteist, communal, sexist, or other motives and biases related to social injustice and inequity, or those appealing to a parochial nationalism intolerant of other cultures and peoples.

Alternative Economies and Technologies

Initiatives that help to create alternatives to the dominant neoliberal or state-dominated economy and the ‘logic’ of growth, such as localisation and decentralisation of basic needs towards self-reliance, respect for and support of diverse livelihoods, producer and consumer collectives, local currencies and trade, non-monetised and equal exchange and the gif economy, production based on ecological principles, innovative technologies that respect ecological and cultural integrity, and moving away from GDP-like indicators of well-being to more qualitative, human-scale ones.

Several examples highlight the above, such as the localised manufacture and the ideas of regional self-reliant economy initiated by the village Kuthambakkam’s ex-sarpanch Elango Ramaswamy. Women in Chennai have moved to replace plastics with environment friendly products as palm plates, bags made of cloth, paper, and jute recycled products. Their venture Nammaboomi manufactures products to combat the throw away culture.

There are several dozen producer companies of farmers, fishers, pastoralists, crafts persons, like the one set up by Timbaktu Collective, Dharani, with an aim to empower villagers especially women and young adults, encourage organic farming, sustainable ways of living and promote environmental conservation and development.

Another example is Goonj’s attempt to create a parallel cashless economy around cloth. Its ‘Cloth for Work and ‘Not Just a Piece of Cloth’ initiative has elevated cloth from its status as disaster relief material to a valuable resource that can generate earning. The initiative works with exchange of two currencies, material and labour, welcoming the old practice of barter and reducing the dependence on monetary resources.

Here too, the Framework cautions against certain type of alternatives: “What may not constitute alternatives, and are superficial and false solutions, such as predominantly market and technological fixes for problems that are deeply social and political, or more generally, ‘green growth’/ ‘green capitalism’ kind of approaches that only tinker around with the existing system.”

Livelihoods

Linked to the search for alternative, localised economies, this includes initiatives for satisfying, dignified, ecologically sustainable livelihoods and jobs. These could be a continuation and enhancement of fulfilling traditional occupations that communities choose to continue if enabling conditions exist, including in agriculture, pastoralism, nomadism, forestry, fisheries, crafts, and others in the primary economy; or they could be jobs in manufacturing and service sectors that are ecologically sustainable and dignified.

Examples of such livelihoods include: the revival of sustainable, organic agriculture by dalit women members of the Deccan Development Society in Telangana who are practicing highly bio-diverse farming methods, treasuring traditional seeds, and initiating the Africa- India Millet Network, which is getting both national as well as international recognition; small farmers associated with Timbaktu Collective in Andhra Pradesh; pastoral initiatives supported by Sahjeevan in Kachchh; and Anthra, a team of women veterinarians in Maharashtra that address the problems faced by small farmers, adivasis, peasants, pastoralists, dalits and women by building a strong base of evidence based practices which are enduring, sustainable, equitable, and respectful of people’s knowledge.

The Timbaktu Collective, Anantapur Dt, Andhra Pradesh

The Food Sovereignty Alliance, a common platform for Adivasis, Dalits, Pastoralists, small and marginal farmers, and social movements to build solidarity in defence of sovereign rights to food and rights of mother earth; the state-run Jharcraft in Jharkhand which has enhanced livelihoods of over 300,000 craft skilled families by creating employment opportunities for the locals and changing the way they perceive art; innovations in Malkha cloth to empower weavers and artisans through stable livelihoods; and unionising waste picker women for more secure, dignified ways of doing their work by recognising waste picking as legitimate work through SWaCH in Pune.

What would not fit are livelihoods, traditional or modern, where non-workers are in control and profiting (monetarily or politically) from the exploitation of workers; this is especially relevant in the current context where many capitalist or state-run corporations are claiming to be eco-friendly, but in the way they treat workers or deal with profits, they remain essentially exploitative.

Settlements and Transportation

This includes the search to make human settlements (rural, urban, rurban) sustainable, equitable, and fulfilling places to live and work in, through sustainable architecture and accessible housing, localized generation of means of satisfying basic needs as far as possible, ecological regeneration, minimisation of waste and its full upcycling or resource use, replacement of toxic products with ecologically sustainable ones, sustaining and reviving the urban commons, decentralised, participatory budgeting and planning of settlements, and promotion of sustainable, equitable means of transport (especially mass, public, and non-motorised).

Examples of such initiatives include: ‘Homes in the City’ in Bhuj programme by several NGOs that aim to empower poor citizens to either self-provision or get access to decent housing, water self-sufficiency, waste management, open spaces and other services; the revival of urban wetlands in Bengaluru and Salem; urban farming such as widespread rooftop gardening in many cities; the waste picker cooperative KKPKP and union SWaCH in Pune and participatory budgeting in Pune, where citizens have a say on how to spend a part of the public budget.

The Framework points out those elitist, costly models that appear to be ecologically sustainable but are not relevant for or affordable by most people, may not fit into alternatives.

Alternative politics

Initiatives and approaches included here are those that aim towards people-centred governance and decision-making, including forms of direct democracy or swaraj in urban and rural areas, linkages of these to each other in larger landscapes, re-imagining current political boundaries to make them more compatible with ecological and cultural contiguities, promotion of the non-party political process, methods of increasing accountability and transparency of the government and of political parties, and progressive policy frameworks.

Some examples reflect the above. The 30-year old story of Mendhalekha, a village that has taken control over its commons and declared that for itself, it is the government, is iconic. It has successfully enforced the long forgotten Maharashtra Gramdan Act of 1965. Through this act the villagers have donated their entire agricultural land to the village Gram Sabha to strengthen it and also secure their land rights (Pathak and Gour-Broome 2001). A decade-long experiment at ecoregional decision making through a people’s parliament ran in the Arvari basin in Rajasthan (Hasnat 2005). There have been movements aimed at gaining citizens’ right to information, independent oversight of governance through lokpals, and public audits (e.g. of the National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme), and others.

Knowledge and media

This includes initiatives using knowledge and media as tools for transformation, including processes using modern and traditional, formal and informal, and urban and rural spheres of knowledge equitably, attempts to make knowledge part of the commons and freely accessible, and alternative and innovative use of media forms for communication.

Examples include the following. The urban SETU programme (Urban Bridge) is a civil society initiative in Bhuj town, Gujarat started in 2007 by workers and activists to equip city dwellers (including those in slums) with knowledge and capacities to understand their rights, various government schemes and policies available for them. CGNetSwara is using mobile and radio technologies to make governance more accessible to far-fung villages of Chhattisgarh.

Environment and Ecology

Initiatives included here promote ecological sustainability, including community-led conservation of land, water and biodiversity, eliminating or minimising pollution and waste, reviving degraded ecosystems, creating awareness leading to greater respect for the sanctity of life and biodiversity of which humans are a part, and promoting ecological ethics.

There are thousands of examples of community conserved areas (CCAs) across India. CCAs are areas where humans and wildlife co-exist. In these times when biological diversity is under grave threat, conservation efforts of the local communities gain immense significance. Even in urban areas, there have been attempts to revive ecosystems in Bengaluru, Udaipur, and Salem. Jheel Sanrakshan Samiti, a people’s organisation formed by concerned citizens of Udaipur in regard to water management and pollution crises has worked tirelessly to ensure lake rejuvenation and combat water issues in the city.

There have been efforts at making tourism more ecologically sensitive as well. Kanchendzonga Conservation Committee (KCC), an organisation that was set up by the local youth of Yuksom village, west Sikkim in 1997, works to balance resource and conservation to make the mountain and tourism development sustainable. The committee promotes village home stays, zero waste trekking, and has formed Ecotourism Service Providers Association of Yuksom (ESPAY). There have also been many initiatives at creating localised curricula and extracurricular material on biodiversity for children and young adults. Superficial solutions to ecological problems, such as planting trees to offset pollution and carbon emissions rather than reducing the emissions, may not be considered alternatives.

Energy

This includes initiatives that encourage alternatives to the current centralized, environmentally damaging and unsustainable sources of energy, as also equitable access to the power grid, including decentralized, community-run renewable sources and micro-grids, equitable access to energy, promoting non-electric energy options such as passive heating and cooling, reducing wastage in transmission and use, putting caps on demand, and advocating energy-saving and efficient materials.

Examples include a large number of decentralised renewable energy projects such as Dharnai micro-grid in Bihar, which was started by Greenpeace India along with Centre for Environment and Energy Development. Another example is of BASIX that launched a project for electrifying a village in Bihar using a solar-powered microgrid. The project aimed to challenge the centralised model of electricity and create a community run and owned system. SELCO, a social enterprise based mostly in southern India works extensively to provide sustainable energy solutions and services to underserved households and small business. It works to create awareness and provide pivotal financial schemes in many remote regions of the country.

What may not count are expensive, elitist technologies and processes that have no relevance to the majority of people; or perhaps even large-scale centralised renewable energy projects with the same problems of access for the poor that fossil-fuel based grid systems have and with significant ecological costs. This latter issue is a major concern with the current government’s large-scale solar energy initiatives.

Learning and Education

This includes initiatives that enable children and others to learn holistically, rooted in local ecologies and cultures but also open to those from elsewhere, focusing not only on the mind but also the hands and the heart, enabling curiosity and questioning along with collective thinking and doing, nurturing a fuller range of collective and individual potentials and relationships, and synergising the formal and the informal, the traditional and modern, the local and global. Examples are aplenty in India, though still marginal compared to the soul-deadening and status quo reinforcing mainstream education.

Examples include: the Ladakhi learning centre SECMOL, which runs an energy self-sufficient campus; Adharshila, a residential school for adivasi children based in Badwani, Madhya Pradesh, that believes in a learning environment that enhances the traditional and cultural knowledge of student’s community; Imlee Mahuaa School for Adivasi communities in and around Balenga Para in the Bastar region of Chhattisgarh, which fosters independent learning environment where children decide what they wish to learn at school; and Karigarshala of Hunnarshala foundation based in Kachchh, Gujarat, started with an objective to capacitate people for reconstruction of their habitat by initiating activities on community empowerment, knowledge networks, and research and development.

Health and Hygiene

Initiatives in this are those that ensure universal good health and healthcare, through the prevention of ill-health in the first place by improving access to nutritious food, water, sanitation, and other determinants of health, ensuring access to curative/ symptomatic facilities to those who have conventionally not had such access, integration of various health systems, traditional and modern, bringing back into popular use the diverse systems from India and outside including indigenous/folk medicine, nature cure, Ayurvedic, Unani and other holistic or integrative approaches, and community based management and control of healthcare and hygiene.

Examples of such initiatives are growing in India. For example, Swasthya Swara based in Chhattisgarh aims to address rural community’s health issues by reviving the traditional herbal/medicinal knowledge of Vaids and Ayurvedic doctors. Similarly, Tribal Health Initiative based in Tamil Nadu works to provide decent health care services to tribal communities living in the Sittilingi valley by initiating a variety of community health care programmes.

Wild Food Festival at Palgarh, Maharashtra,

Food and Water

This includes initiatives towards security and sovereignty over food and water, by producing and making accessible safe and nutritious food, sustaining the diversity of Indian cuisine, ensuring community control over processes of food production and distribution, and commons from where uncultivated foods are obtained, promoting uncultivated and ‘wild’ foods, making water storage, use and distribution decentralised, ecologically sustainable, efficient and equitable, producer-consumer links, advocating the continuation of water as part of the commons, and promoting democratic governance of water and wetlands.

There are several examples of the above in India. Deccan Development Society and Timbaktu Collective are mentioned above. Apart from these, Gorus Organic Farming Association around Pune is working on the model of Community Supported Agriculture by training small farmers in organic and natural farming practices and providing a market with a year-round guarantee of purchase at an assured price. Another example is of Arid Communities and Technologies (ACT) based in Kachchh, Gujarat, that works to strengthen the livelihoods of communities in arid and semiarid areas by resolving ecological constraints through facilitation and access to technologies or institutional solutions. The focus is on groundwater management and urban watershed management. Many more examples are available on India Water Portal (http://www.indiawaterportal. org/)

Purely elitist food fads even if they pertain to healthy or organic food, and expensive technological water solutions that have no relevance for the majority of people, are unlikely to be considered as alternatives.

Global Relations

These encompass state or civil society initiatives that, in the words of the Framework, “offer an alternative to the prevalent state of dog-eat-dog, belligerent and hyper-competitive international relations fuelled by geopolitical rivalries”. These include cross-national dialogues among citizens and diplomats, moratoriums on increases and gradual decrease in military, surveillance and police spending, bans on ‘harms’ trading (e.g. arms, toxic chemicals, waste), and even re-examining notions of ‘nation state’ and emphasising relations amongst ‘peoples’ of the world.

Examples include several people-to people dialogues between citizens of India and Pakistan, and the positive (mostly in the past) advocacy of disarmament, non-alignment, environmental sustainability and other such global policies by India and Indian civil society.

What would not count as an alternative, is the attempt by India and other emerging powerful economies (the BRICS nations) to provide a counter to the power of the USA and Europe, for even as it does so, it follows the same neoliberal, state, corporate dominated policies that the industrialised countries have done so far (Bond 2015).

References:

Bond 2015, Patrick and Garcia, Ana (eds). 2015. BRICS: An anti-capitalist critique. Jacana Media, Johannesburg.

Pathak, N. and Gour-Broome, V. 2001. Tribal Self-Rule and Natural Resource Management: Community based conservation at Mendha-Lekha, Maharashtra, India. Kalpavriksh, Pune and International Institute of Environment and Development, London.