India, accounting for around 17% of the world population has been endowed with just four percent[1] of the world’s fresh water resources, which clearly highlights the need for its judicious use. Following the Falkenmark Index, more than half of the twenty river basins have water scarcity conditions with availability of less than 1000 m3 per capita per annum. According to a report of the Union Water Resources Ministry, total water demand in the country is estimated to increase by 34 percent by 2025 and over 78 percent by 2050, indicating a major gap of around 30 percent with respect to the replenishment rate capacity signaling a serious water crisis in the nation.

Water has been identified as a critical resource in India’s public policy more than three decades ago. It brought the first national water policy in 1987 and revised in 2002. However, the water crisis continues to augment. In 2012, the government of India adopted a fresh National Water Policy, which provided for significant change in our approach and action. This policy draws principles of water resource management from globally recognized sustainable systems such as Integrated River Basin Management, Conjunctive water management and aquifer as unit of ground water management. However, even after six years of the adoption the policy, there has been no progress on implementation of this policy. On the other hand, the water crisis continues to loom. This article is an attempt to understand the gravity of current water crisis, its future risks and policy solutions.

An Overview of the Status of Water Resources in India

Water Resource Potential of India

The main source of water in India consists of precipitation including snowfall which is estimated to be 4000 km3 and trans-boundary flows received in its rivers and aquifers from the upper riparian countries,[2] which is approximately 500 km3. The average annual natural flow in rivers and aquifers is approximated to be 1869.3 billion cubic meters (BCM) considering the loss due to evapotranspiration. Further, due to various topographical, technological and resource constraints[3], only about 1123 cubic km3 can be accessed yearly by India. (See table-1).

Table-1: Water Resources of India

| Estimated annual precipitation (including snowfall) | 4000 km3 |

| Run-off received from upper riparian countries (approx) | 500 km3 |

| Average annual natural flow in rivers and aquifers | 2301 km3 |

| Estimated utilizable water | 1123 km3 |

| (i) Surface | 690 km3 |

| (ii) Ground | 433 km3 |

Source: Water Mission, NAPCC

While the precipitation is major source of water, it is distributed highly uneven across the country and over the year. For a large part of the country, it is concentrated in the Monsoon season during June to September or October. Precipitation also varies from region to region.The annual rainfall varies from 100 mm in western part of India (Rajasthan) to 11000 mm in Cherrapunji in Meghalaya[4]. This flows into nearly 2 lakh km of rivers and 7.5 million hectares of lakes, pond, underground aquifers and reservoirs/tanks constructed by people and governments (see table-2).

Table-2: Inland Water Resources of India

| Length of Rivers and Canals (in Km.) | 1,95,095 Km |

| Other Water Bodies (Area in Million Hectare) | |

| – Reservoirs | 2.93 M.Ha |

| – Tanks and Ponds | 2.43 M.Ha |

| – Flood Plain Lakes & Derelict Water bodies | 0.80 M.Ha |

| – Brackish Water | 1.15 M. Ha. |

Source: EnviStatsIndia- 2018

Water resources in India is limited and geographical distribution ranges from highly wet areas to extreme dry regions. However, it has been observed that even in traditionally wet regions, people are now struggling for drinking and irrigation water due to many reasons. Therefore, the management of water resources is crucial to use this resource in more sustainable manner.

To meet water demand there has been a high focus on creating water reservoirs and water storage structures. According to River Basin Atlas published by WRIS in 2010, there were 4728 operational dams and 397 under constructed dams in India. These dams had capacity of storing about 304 BCM water. An additional live storage capacity of six BCM had been created through medium storage projects[5]. However, despite the huge live storage capacity created over the decades, the large population remained deprived of drinking and irrigation water.

The latest NFHS survey (NFHS-4, 2015-16) reveals that more than 10% people do not have access to clean drinking water and more than 50% people do have access to improved sanitation facilities. In terms of irrigation, only about 90 million-hectare land is irrigated. The Maharashtra has 40% of country’s large dams but nearly 82% of agriculture land of the state is rain fed[6].

Demand- Supply Gap

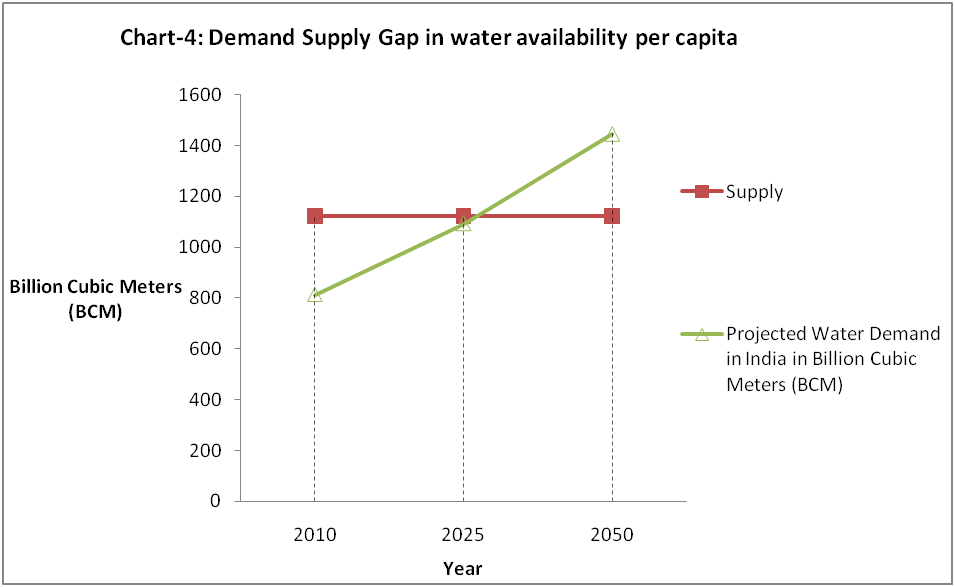

According to the Ministry of Water Resources, the total demand of water in India was 813 BCM in 2010, which is estimated to increase to 1093 BCM by 2025 and 1447 BCM by 2050. This clearly indicates the gap in demand and supply, and in the near future, with growing population and thus the demand, the total demand for the country as a whole would be higher than the total replenishable water capacity of India (1123 BCM).

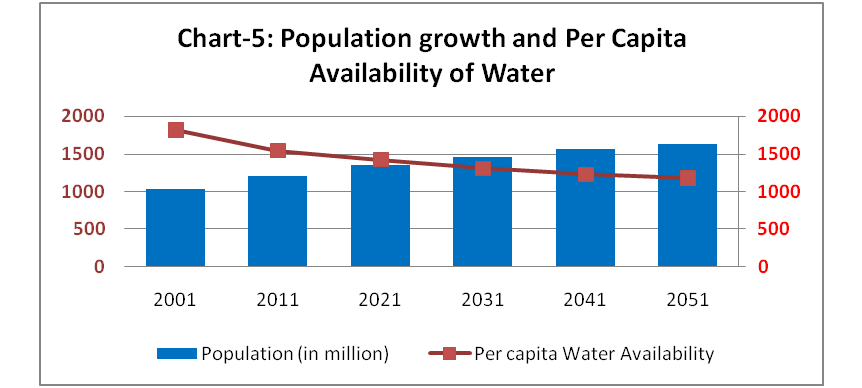

Further, the crisis is compounded by an increasing population, which results in a mounting pressure on the water resources of the country. According to the Water and Related Statistics published by the Central Water Commission, per capita annual availability of water in the country has decreased from 1816 cubic meters in 2001 to 1545 cubic meters in 2011[7], and is likely to further fall to 1421 by 2021 and 1174 by 2051[8].As per the Falkenmark Index, one of the most commonly used index of water scarcity, if per capita water availability decreases below 1700 M3 per year the condition is termed as water stress. If it further decreases and goes below 1000M3 per annum the condition is termed at water scarcity.

While at the aggregate level, the utilizable potential stands at 1123 BCM, the water availability at the disaggregate level depends on several other factors and it varies both, temporally and spatially. The major source of water for India i.e. precipitation is highly uneven in its distribution. Owing to the large spatial and temporal variability in the rainfall, water resources distribution is highly skewed in space and time.[9]Therefore even while the overall picture shows a demand supply gap which will begin to worsen only in the near future, many regions in the country have already started to witness water scarcity conditions due to shrinking water resources in their close vicinity, including depleting level of groundwater.

Reducing the Gap: Solutions to water management

Source: Envistats- India- 2018: Environmental Accounts[10]

The supply of the water is constant and in fact, decreasing but the demand is on rise. Some estimate shows that between 2025 and 2030 the total water demand of India will surpass the total available water. Moreover, the increasing rate of evapotranspiration is major concern, which is resulting into decline in total water available for various human uses. Scientist have observed that decline in the rate of water recharge due to erratic whether, melting glaciers due to global warming and rapid spread of water pollution due to untreated discharge of sewage & industrial waste and use of excessive chemical in agriculture. All these problems are manifestations of unsustainable and consumerist world order, which has now pose serious related to water risks. There are chances to reduce these risks by changing our behaviour and re-working on designing and implementation of sustainable policies. Within the policy space there is a need to adopt integrated approach and address both the issue of supply and demand of water. This section briefly describes possible policy recommendations to address current water crisis in India.

Supply Side Solutions

India has a strong history of policy driven management of water resources. The First national water policy adopted by the country in 1987 prioritized water uses. The drinking water was given first priority in this policy. We revised our water policy in 2002. The latest national water policy was adopted by the country in 2012 and it emphasizes on adopting integrated river basin management approach to manage water resources in more sustainable manner.

A river basin approach comprises the entire catchment area and therefore acknowledges and strives to maintain all ecological services available in the catchment area. According to WWF the integrated river basin management approach rests on the principle that naturally functioning river basin ecosystem, including accompanying wet land and groundwater system[11].

River Basin and Aquifer as Unit of Water Management

To manage supply of water resources in more sustainable manner, the river basin approach is much needed policy intervention. The high powered committee constituted by the government in 2015 led by Dr. Mihir Shah has also strongly advocated for adopting integrated approach to deal with the issue of water crisis. The committee took the idea of the National Water Policy 2012 further and recommended for structural changes in the system of water governance. Now these recommendations need to be converted into policy without any further delay.

Within the integrated approach of water resource management, there is need to change the way we manages ground water. Acclaimed ground water expert Dr. Himanshu Kulkarni, argues that aquifer is unit of ground water with limit defined by physical and hydraulic boundaries. Major ground water policies/schemes in India looks at the supply and augmentation side of ground water resource without any consideration of aquifer. The Easement Act, 1882 freely entitles the owners of land to collect and dispose the water under their land. This leads to an unregulated proliferation of wells and borewells. There is virtually no legal liability for them to cause any damage to water resources including over extraction of ground water. Dr. Kulkarni advocates for recognizing ground water as public good by removing provisions of the Easement Act, 1882 allowing land owner to extract ground water without any regulations.

Demand Side Solutions

Agriculture and Irrigation

Out of total available water 813 BCM in India, agriculture demands nearly 84% (688 BCM) for production in the form of irrigation. The coverage of irrigation has significantly increased in India after independence and currently it has potential to provide irrigation facility to nearly 113 million hectare land across the country. However only 89 million hectare land actually utilizes irrigation facility provided through various means. This demand will further increase to 910BCM in 2025 and 1072BCM in 2050[12]. With this estimate in next 30 years, the water demand for irrigation will overshoot the total fresh water available in the country. According to a recent study by NABARD, the three water guzzler crops namely rice, sugarcane and wheat consumes more than 50% of total water for irrigation in India[13].

Table-3: Production and Water Consumption by Water Guzzler Crops in India

| Crop | Total Cropped Area (million hectare) | % of Gross Cropped Area | Total Production (million tons) | Total Consumptive Water Use

TCWU (Km3) |

Irrigation coverage (%) |

| Rice | 43 | 22 | 110 | 206.2 | 59.6 |

| Wheat | 30 | 16 | 98 | 82.7 | 93.6 |

| Sugarcane | 4 | 3 | 306 | 57.4 | 95.3 |

Source: Agricultural Statistics, 2017 and NABARD, 2018

The three water guzzler crops namely rice, wheat and sugarcane cultivation together consume around 346 BCM water. It accounts more than 50% of total water demand for agriculture in India. Surprisingly larger producers of these crops are state which are water stressed such as Punjab, Andhra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Haryana and Gujarat. The ground water meets nearly two third of irrigation water in India and the groundwater data shows that states leading in cultivation of wheat, rice and sugarcane such as Punjab, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, Haryana and Tamil Nadu have over extracted their ground water reserve.

Suggested Policy Solutions

Re-alignment of Cropping Pattern: the high production of water intensive crops like sugarcane and rice in water stressed states such as Punjab, Haryana, Maharashtra, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu is because of system of procurement through government at assured price especially for rice and establishment of sugar mills to process sugarcane developed in these states over a period. Surprisingly production of these water intensive crops in wet part of the country such as eastern Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Odisha and Assam is less. In order to make our agriculture more sustainable there is need to re-align cropping pattern in the country. Incentivising water intensive crops in the wet part and less water intensive crops in water stressed areas will help in this re-alignment.

Irrigation Infrastructure Improvement: India has spent huge amount to create large, medium and small project for irrigation after independence. However, of the total 113 million hectare irrigation potential, the country is able to utilize only 89 million hectare land. This gap is further increasing as we have paid little attention on distribution of water. While it is necessary to strengthen irrigation water distribution system by involving people and decentralizing them, it is also necessary to promote new and efficient irrigation technologies such as micro irrigation.

Conjunctive Water Management: The ground water meets nearly two-third of our water demand for irrigation. After green revolution, the share of ground water for irrigation has tremendously increased due to various policy and technological reasons. This has resulted in rapid decline in water table in many states. The conjunctive use of water to meet our various demands is way out. The conjunctive management approach in this sector attempts to use surface water, ground water and other water bodies in unified and comprehensive manner.The conjunctive use must also incorporate new ideas of water harvesting, storage and distribution. Bhungroo technology innovated by social entrepreneurs Biplab Paul and Trupti Jain of Naireet Services[14], based in Gujarat is one such idea. The Bhungroo technology tries to store accumulated rainwater in s specific cavity identified underground through a drilled hollow pipe. This hollow pipe is called Bhungroo in Gujarati, which also can be used to lift water from the cavity for irrigation, when needed.

Climate Resilient Agriculture:with rapid change in climatic conditions and higher risk to crop production, there is need to innovate, promote and adopt climate resilient agriculture. Apart from new technologies on climate resilience, traditional agriculture also teaches us to grow climate resilient crops. There are thousands of indigenous seed varieties for all major crops in India and these variations in seeds used to diversified our agriculture production and sustain us against any drastic climatic change.

Policy Reform:India has large web of policies related to farm and farmer, many of them are unsustainable and risky for the future of agriculture production. For example use of unregulated tube wells with free or subsidised electricity to run them were introduced to solve the problem of irrigation. But, now this solution has become a problem as excessive underground water extracted by these tube wells has drastically depleted the water table. Such policies needs to re-visited to correct them for more sustainable future.

Drinking Water

According to an official estimate, the water demand for domestic use is 56BCM, which is projected to increase by 73 BCM in 2025 and 102 BCM in 2050. The major part of this demand is met through groundwater resources – 85% of India’s rural domestic water requirements and 50% of its urban water requirements are met from ground water. Providing safe drinking water to all is still a big challenge. According to NFHS, 2015-16, more than 10% people in the country do not have access to clean drinking water and more than 50% people do not have access to improved sanitation facilities. According to Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation of the total 17,26,031 rural habitations only 77% have access to drinking water.

Water quality for 4.2% habitations is highly contaminated due to sewage discharge and untreated discharge from industries[15].The current gap between demand and supply for drinking water both in rural and urban is huge. We are unable to provide minimum 40 litres per capita per day (lpcd) to all in rural areas. Similarly, the standard water requirement in urban areas is 135 lpcd of which our total urban supply is merely 69 lpcd[16]. This is bound to increase in near future if radical policy interventions are not adopted. Following policy initiatives suggested by various experts and organizations can be adopted to address risks related to drinking water.

Arresting Water Pollution: The water pollution has come up in big way in last few decades and became a major challenge for water portability. Available data suggests that pollution level has increased in surface water as well as ground water. Moreover, the pollution is spreading rapidly and contaminating more water bodies. The main sources of water pollution are discharge from sewage, industry and use of fertilizers and pesticides. The prevention of pollution of water sources is critical in order to continue to portable water supply. The government of India has identified 19 states severally affected high fluoride content in drinking water and at least 10 states suffering from arsenic contamination leading to diseases that affect lungs, skin, kidney and liver[17]. While public awareness and capacity building of local people is important to keep water bodies free from contamination, it is also important to find policy solutions to ensure sustainable use of chemicals and proper treatment of sewage and industrial waste.

Decreasing Slippage: Slippage is yet another major problem in achieving goal of universal access to safe drinking water. Data of Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation reveals that the coverage of safe drinking water has only increased from 74% in 2012 to 77% in 2017. Slippage in this context means fully covered habitation slowly slips back to non-covered or partially covered state due to shortage of water. Erratic whether, depletion of ground water, reduction of water bodies and pollutions are some major reason behind slippages. Unfortunately, this has become a recurrent problem especially in rural areas. Therefore, intergraded approach of water resource management is needed for schemes related to drinking water supply.

Curbing Water Leakage and Pilferage: The national water policy, 2012 suggest to local urban bodies to collect and publish water account and audit report to fix the problem of leakage and pilferage. Several studies on water leakages in India indicate that about 30% to 50% water in urban supply is lost due to leakages, theft, unauthorised connections and incorrect metering[18].

Conclusion and Way Forward

As has been discussed in the section on An Overview of the Status of Water Resources in India, the water resources in the country are under stress. Although India has 4 per cent of the total water resource in the world, but it is much less than proportionate when we take into account that India has 17% of the world population. The demand-supply gap for the country as a whole has been estimated to be imbalanced (with demand over shooting supply) in the near future; however many regions are already suffering from conditions of water scarcity and drought. This situation, which affects both rural and urban areas, is further compounded by climate change, which not only would lead to erratic rainfalls and shrinking glaciers but also would make the extreme weather events like floods and cyclones much more common. It would put to risk the living standards of 60 million Indians, as has been highlighted by a 2018 World Bank report[19] on South Asian Hotspots. It is thus important to have adequate mechanism and policy framework considering that the supply of water is constant and in fact depleting over time as against rapid increase in demand. The country is already in deep water crisis and it is expected to worsen in near future if radical corrective measures are not taken now.

References:

[1] IITM: Climate Change Impact on Water Resources in India, Keysheet-5, IITM

[2] National Water Mission under National Action Plan on Climate Change, 2008 (Vol-II), Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India.

[3] National Water Mission under National Action Plan on Climate Change, 2008 (Vol-II), Ministry of Water Resources, Government of India.

[4]Ibid

[5]http://www.india-wris.nrsc.gov.in/Publications/RiverBasinAtlasChapters/RiverBasinAtlas_Full.pdf

[6]High Powered Committee Report, 2016, ‘A 21st Century Institutional Architecture for India’s Water Reforms’, July, 2016, Government of India.

[7]Chapter 3- Water: The Nectar of Life, EnviStats India 2018. (Supplement on Environmental Accounts) http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/reports_and_publication/statistical_publication/EnviStats/5_Chapter%203%20-%20Water.pdf

[8]Chapter 3- Water: The Nectar of Life, EnviStats India 2018. (Supplement on Environmental Accounts) http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/reports_and_publication/statistical_publication/EnviStats/5_Chapter%203%20-%20Water.pdf

[9]http://www.fao.org/nr/water/aquastat/countries_regions/IND

[10]Chapter 3- Water: The Nectar of Life, EnviStats India 2018. (Supplement on Environmental Accounts) http://www.mospi.gov.in/sites/default/files/reports_and_publication/statistical_publication/EnviStats/5_Chapter%203%20-%20Water.pdf

[11] WWF: https://wwf.panda.org/our_work/water/rivers/irbm/, Accessed on 28.03.19

[12]Envistats India, 2018, Envi Stats India-2018: Supplement on Environmental Account, MoSPI, government of India.

[13] NABARD, 2018, Water Productivity Mapping of Major Indian Crops, NABARD, India.

[14]https://www.naireetaservices.com/

[15] Water Aid India: http://wateraidindia.in/faq/drinking-water-problems-india/ , Accessed on 30.03.19

[16] TERI: Syed Qazi, Waming Ali and Nathaniel B Dkhar, ‘India’s rampant urban water issues and Challenges’ December, 2018, TERI, Accessed from:https://www.teriin.org/article/indias-rampant-urban-water-issues-and-challenges, Accessed on 29.03.19

[17] Water Aid India: http://wateraidindia.in/faq/water-quality-quality-water-available-india/ , Accessed on 30.03.19

[18]Public Information Bureau: http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=84072, Accessed on 30.3.19

[19]Mani, M., Bandyopadhyay, S., Chonabayashi, S., Markandya, A., & Mosier, T. (2018). South Asias Hotspots: The Impact of Temperature and Precipitation Changes on Living Standards. The World Bank Group. doi:doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1155-5.