Introduction

The European Union (EU) in October 2023 had rolled out a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The mechanism is set to come in force from January 2026 and imposes a carbon tax on certain products imported by EU member countries from non-EU member countries.

The imposition of carbon tax through CBAM is in the name of climate change mitigation strategy. The CBAM regulation document states that the objective of the policy is to prevent carbon leakages and also encourage trade partners of the EU to reduce carbon emission intensity of their production.

The financial implication of the CBAM will start from its second phase starting from January 2026. However, various institutions, business houses, governments and multilateral institutions have started assessing financial and trade implications of the CBAM. The issue has also been raised by India in the thirteenth ministerial conference of WTO held in February 2024. Countries like India and South Africa have argued that the CBAM is against free trade agreements of the WTO.

The CBAM has clear implications on domestic climate mitigation strategies of various countries exporting high carbon intensive products to the EU. The implication of the CBAM on domestic climate policies and targets has not been explored yet. This paper is an attempt to compare and contrast CBAM and India’s climate change strategy.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism Details

The CBAM is a new carbon tax proposed by the EU that will significantly change global production and trade of selected high carbon intensive products. The core argument of the EU is that the production of selected products by non-EU countries covered by this policy must pay a carbon tax equivalent to carbon tax paid by their EU based producers. The EU has further argued that the new tax policy is compatible with the WTO rules and encourages cleaner industrial production in non-EU Countries[1].

The CBAM is currently designed for taxing six non-EU productions namely Cement, Iron and Steel, Aluminum, Fertilizers, Electricity and Hydrogen. The carbon tax in the EU regulated by EU-ETS is one of highest in the world. Therefore, developing countries where carbon taxes are not imposed or are not that high will suffer while exporting to the EU. The mechanism calculates a carbon tax both on direct embedded emission of CO2 and indirect embedded emission of CO2 such as production of electricity used for the production of CBAM covered items.

The importer will have to furnish actual direct and indirect emission data and carbon tax paid in its country of origin. This data will be used for calculating the carbon tax to be imposed on a particular imported item. In the absence of actual direct and indirect embedded emission of an imported item, default rate of tax will be imposed under the CBAM. The carbon tax already paid in the country of origin will be deducted from the price of carbon emission calculated as per guidelines of the CBAM.

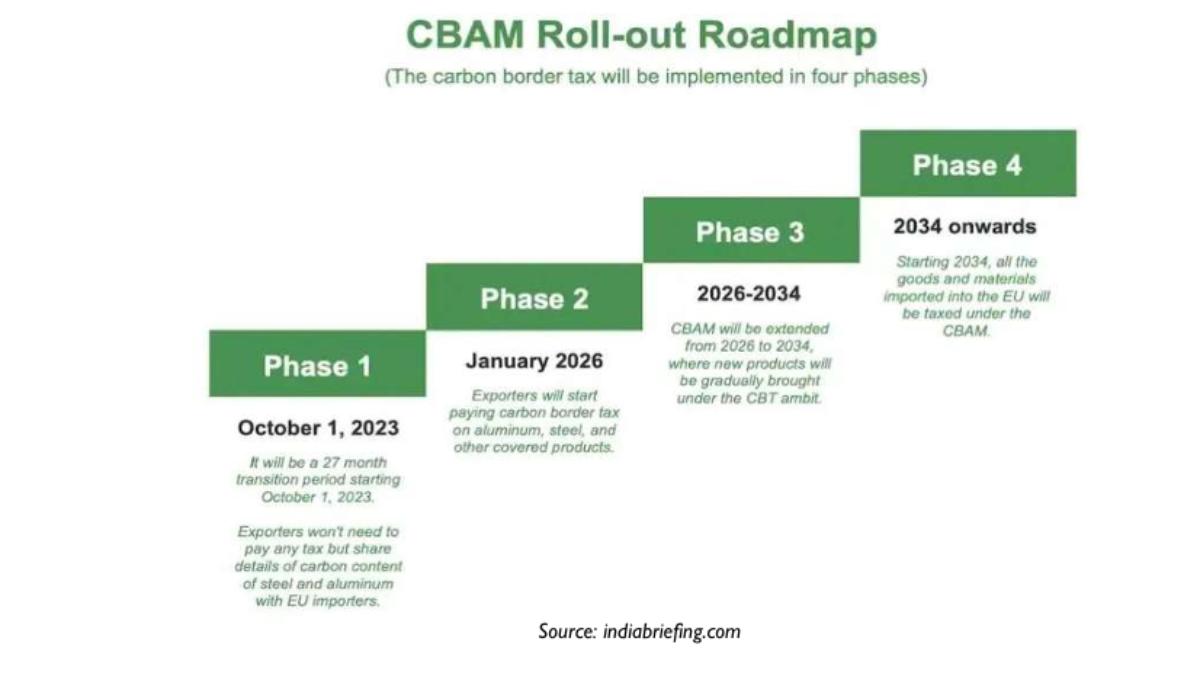

The implementation of the CBAM is divided into different phases. The first phase of the CBAM began in October 2023 and will end in December 2025. This phase is also called transition phase, where no carbon tax under the CBAM will be levied on an import of covered items from the non-EU countries. This 27 month long phase will, however, require importers in the EU country to furnish reports of direct and indirect embedded carbon emission to the registry of the CBAM. The report will also reveal the total carbon price due in the country of origin.

The second phase of the CBAM will begin in January 2026 when the EU will start collecting carbon price on selected six imported items through CBAM certificates. The calculation of embedded carbon emission will only be calculated by methods developed by the EU. Moreover, in the absence of actual emission data, the default value used for calculation of the carbon price will also be decided by the EU[2]. This phase of the CBAM will continue till 2034, which is co-terminus with its domestic incentives for various industrial sectors. In this period more items may be added under the CBAM. The EU aims to bring every import under CBAM from 2034 onwards.

The total annual import budget of the EU with regards to selected six sectors covered by CBAM namely Steel and Iron, Aluminum, Cement, Fertilizer, Hydrogen and Electricity is more than USD 1 billion[3]. Taxing this import for carbon will adversely affect exports of low income and developing countries.

Relative CBAM Exposure Index of India

The World Bank has developed a CBAM Exposure Index to assess the economic implication of CBAM on countries exporting CBAM products to the EU. According to this index, India has a higher CBAM Exposure Index in the sector of Iron and Steel. Its export of Iron and steel as per this index is around 23.5% of the total iron and steel export of India[4]. The CO2 equivalent emission intensity of India’s iron and steel is 2.01 kg CO2eq/USD. The carbon intensity of Indian cement is as high as 9.09 Kg CO2eq/USD. However, it will have low impact on India’s overall all CBAM exposure due to low volume of cement export to the EU.

| Sector | CO2 emission Intensity of Exported Product

(Kg CO2eq/USD) |

Export to EU (of the total global export) | Relative CBAM Exposure Index |

| Steel and Iron | 2.01 | 23.5% | 0.04 |

| Fertilizers | 1.39 | 1.1% | 0.001 |

| Electricity | – | – | – |

| Cement | 7.09 | 0.6% | 0.001 |

| Aluminum | 0.33 | 9.1% | 0.002 |

Source: The World Bank

A positive relative exposure index indicates that an economy has higher carbon emission intensity than EU average and so will likely have higher costs under CBAM. The aggregate CBAM exposure Index of India is 0.03, which is fifth highest in the world. Top five countries with higher carbon emission intensity than the EU are Zimbabwe (0.087), Ukraine (0.053), Georgia (0.046) and Mozambique (0.045). The CBAM exposure index of India in the steel and iron sector is second highest along with Ukraine (0.04). Zimbabwe produces the highest carbon intensive steel.

Aggregate Relative CBAM Exposure Index of India

| Most Affected Sector | Steel and Iron |

| Product Export to EU (%of GDP) | 0.1% |

| EU Share in Export of CBAM Products | 18.9% |

| Overall relative CBAM exposure Index | 0.03 |

Source: The World Bank

An analysis by the Asian Development Bank based on the Relative CBAM exposure index calculated by the World Bank found that fast developing economies such as South Africa, India and the Russian Federation have to pay a very high carbon price on its export to the EU under the CBAM. This analysis calculates CBAM carbon price in the sector of base metal production by multiplying the carbon intensity with the carbon price difference between the EU and other countries, using EU carbon price of USD 96.30. It found that South Africa will have to pay the highest rate of CBAM carbon tax – 68.2% of its basic metal export. As per this analysis India will have to pay the second highest rate of carbon tax – 38.8% of its export of basic metal[5].

CBAM’s Impact on India’s Exports

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism will adversely affect countries exporting CBAM covered items to the EU. This impacting the form of financial loss is going to hit more to developing countries and emerging economies such as India and Turkey. The domestic carbon tax in these countries is much lower than carbon tax charged by EU ETS in the European market. Realizing this threat the government of India has officially registered its objections against CBAM in a recent meeting of WTO. India has argued that the idea of CBAM goes against free trade principles of the WTO. The Commerce Secretary of India Mr. Sunil Barthawal argued that the CBAM is a unilateral measure of trade protection, which is sought to be justified in the guise of environmental protection[6].

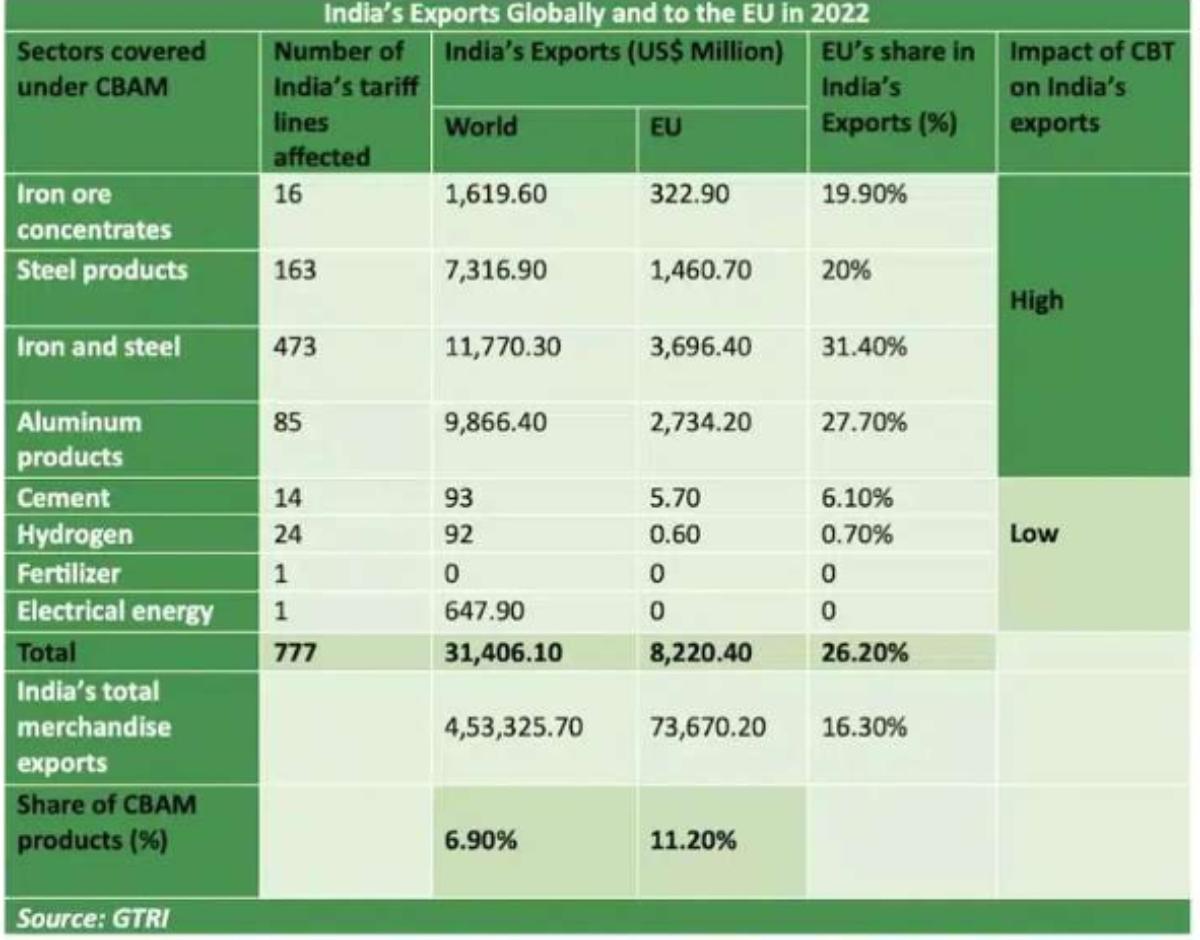

Of the six items covered under CBAM, India is going to be affected significantly in two sectors namely iron and steel, and aluminum. These two sectors include iron ore concentrates, steel products, iron and steel and aluminum products. Nearly one third (31%) of India’s export of iron and steel is to EU. Moreover, the EU is a significant trade partner of Indian exports in the sectors of iron ore concentrates (20% of total export), steel products (20%) and aluminum products (27.7% of the total export).

Other sectors affected by CBAM are India’s export of cement to the EU. India exports nearly 6% of its total cement export to the EU. This sector is also a carbon intensive sector that will see huge imposition of carbon tax on its import. Other sectors included in the CBAM namely fertilizers, hydrogen and electricity have insignificant impact on India’s export as there is very little or no export of these items from India to the EU. An analysis of the impact in the Iron and Steel sector is done separately in the latter part of this article.

Impact of CBAM on India’s Net-Zero Pathways

India has always been a serious and proactive member of global negotiations and collaborations on climate change. Right from the Stockholm Conference in 1972 to till now, India played an important role in leading climate actions and advocating common and differentiated responsibility to address issues pertaining to climate change. India’s proactive efforts can also be assessed by accepting and meeting the Bonn Challenge of the IUCN, timely submission of its Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) and setting 2070 as net-zero target to itself. India in 26th Conference of Parties of UNFCCC held in Glasgow in 2021 declared that India will streamline its all efforts to meet net zero target by 2070.

Such a consistent approach of India irrespective of its domestic political complexities is important because India is the third largest emitter of Green House Gases after China and the United States of America. However, the per capita emission of India is much less compared to many countries in the world. The roll out of CBAM will currently affect India’s steel trade but with extension of this policy in other sectors will adversely affect rapidly growing economies such as India.

The impact of CBAM in the long run will be to affect social, environmental and climate policies of developing countries. This section is an attempt to highlight the possible impact of CBAM on India’s Low Carbon Strategy and Net Zero pathways.

CBAM versus the CBDR-RC Principle of UNFCCC

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), 1992 is the foundational arrangement for all international climate change negotiations and collaborative actions for climate change mitigation and adaptation. 198 member nations including India and European nations are parties to this convention.

The UNFCCC treaty document is based on five principles that brings together all parties and encourages mutual cooperation and collaboration for collective climate actions. The first and foremost principle of UNFCCC is – Common But Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC). The treaty document reads:

“The Parties should protect the climate system for the benefit of present and future generations of humankind, on the basis of equity and in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities. Accordingly, the developed country Parties should take the lead in combating climate change and the adverse effects thereof[7].”

The second principle of the treaty further strengthens the idea of equity by acknowledging special circumstances and specific needs of developing countries. These principles follow with commitments signed by parties in accordance with their common but differentiated responsibilities and their specific national and regional development priorities.

The introduction of CBAM rolled out by the EU goes against stated principles of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and common and differentiated commitments formula agreed by parties of the convention. In the core of CBAM the EU has argued that it will work as a tool to impose fair price on emitted carbon during the production of carbon intensive products in non-EU countries. The carbon price imposed by the EU Emission Trading System (ETS) is one of the highest in the world. With the help of CBAM, the EU wants to impose an equal carbon price on all carbon intensive goods produced in non-EU countries, exported to the EU.

The high price of carbon under the EU ETS is part of their obligation under the UNFCCC as Annex-I countries of the treaty. As per the convention treaty countries listed as Annex-I have greater responsibility and mitigation role. Being Annex-I countries, members of the EU are bound to have such carbon pricing for their production. But, imposing the same rate of carbon price on other countries especially non annex-I countries (developing countries) goes against the principle of common but differentiated responsibility and respective capabilities.

The roll out of CBAM is a unilateral imposition of carbon price beyond the capabilities of non-annex countries (developing countries) including India. Moreover, it seems to be an attempt of the EU countries to outsource its own differentiated commitment of a high mitigation role under the UNFCCC. India’s Low Carbon Development Strategy

In pursuance of the Paris Agreement adopted by parties with UNFCCC in 2015, India has recently developed its Long-Term Low Carbon Development Strategy (LT LCD) in 2022. This document officially declares India’s roadmap in the long run to meet its Net Zero commitment by 2070. This document gives a framework of strategy for different carbon intensive sectors. Overall, India’s long term low carbon strategy is based on following three principles as described in its introduction chapter[8].

- Low Carbon Footprints of India:India recognizes climate change as a collective action problem and continues to be the main partner despite its very minimal contribution in GHGs accumulation. The strategy document claims that India’s historical contribution to the “accumulation of GHGs is about 4% even though it is home to nearly 17% of the global population.”

- CBDR-RC:India firmly believes in equity through the Common but Differentiated Responsibility and Respective Capabilities (CBDR-RC) as laid out in the treaty document of United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

- Equitable Carbon Budget:India is drawing a very small portion of the carbon budget. The carbon budget should be equitably distributed among all countries and utilized responsibly. India should be allowed to use its fair share of global carbon budget on the basis of CBDR-RC

The Long term low carbon development strategy released by India in 2022 is in accordance with the Paris Agreement and it heavily banks on an internationally agreed framework and principles of equitable sharing of mitigation responsibility. The roll out of the CBAM forces developing countries to cut down their fair share of the carbon budget. For instance, India has its own national circumstances and development needs. To meet its developmental needs, India has to draw from the global carbon budget.

The Paris Agreement is legally binding on parties with the UNFCCC; however it gives autonomy to parties to set their own mitigation targets in the form of NDCs. The idea behind updating of NDCs every five year provides space for parties to incorporate new science and technology in their mitigation plan in order to make incremental progress. The LT LCD is the articulation of countries’ longer vision statements connected to periodically updated NDCs. The CBAM is an attempt to undermine NDCs and therefore disrupt LT LCD of developing countries exporting carbon intensive products to the EU.

India’s Iron and Steel Industry and its Carbon Intensity

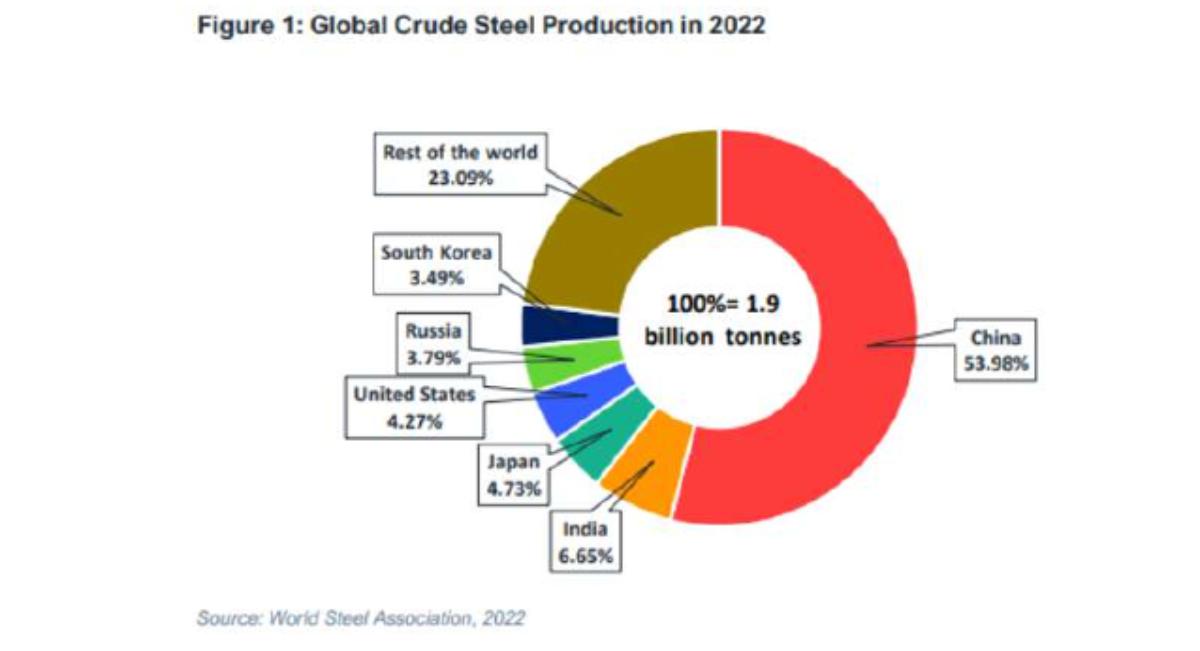

The iron and steel industry of India is the major sector affected by the CBAM policy of the EU. India is the second largest producer of crude steel in the world accounting 6.65% of total global production. The People’s Republic of China is the biggest producer of crude steel and produces around 54% of global steel. Other major steel producing countries include Japan (4.73%), United States (4.27%), Russia (3.79%) and South Korea (3.49%). The accumulated production of crude steel by these six countries is nearly 78% of the global production. All of these countries export a sizable iron and steel products to the EU. Russia exports more than 29% of its iron and steel to the EU followed by India (23.5%). The EU as a block is the largest importer of iron and steel and imports more than 11 million metric tonnes of iron every year[9]. China, India, Russia and South Korea are amongst the top ten sources of EU’s steel and iron imports.

India as a key source of iron and steel products of the EU is the biggest import source for stainless steels and amongst first five top sources in the category of semi-finished steel and flat products. With the introduction of CBAM, India is likely to be affected more as it has the highest CBAM exposure index of 0.044 amongst largest crude steel producers in this category. This high CBAM exposure of India is due to very low carbon tax in India and very high carbon intensity production of steel and iron. According to the World Bank statistics India’s carbon emission intensity of exported iron and steel is 2.01 KG CO2eq/USD. This is the fourth highest carbon emission intensity after Nigeria, Laos and Kazakhstan[10].

Steel production is high energy consuming in India compared to other countries. According to the data of the Union Ministry of Steel, the energy consumption of steel plants in India is 6 to 6.5 Giga Calorie per tonne of crude steel compared to 4.5 to 5 Giga calories per tonne abroad[11].

Being the second largest producer of the crude iron, India produced 125 million metric tonnes in 2022. The sector has observed steady growth in the last five years. India is a net exporter of crude iron and steel. It had exported 8824 thousand Tonnes in 2021-22 and 695 thousand tonnes in 2022-23[12].

To further explain the carbon footprint of the Indian steel sector, a recent report of Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) reveals that the steel sector accounts for about 12% of India’s carbon dioxide emissions. It further states that the carbon emission intensity is 2.55 tonnes of CO2/tonne of crude steel compared to the global average of 1.85 tCO2/tcs. This sector is responsible for emitting 240 million tonnes of CO2 and is expected to increase exponentially as the domestic and international demand of steel and iron is increasing[13].

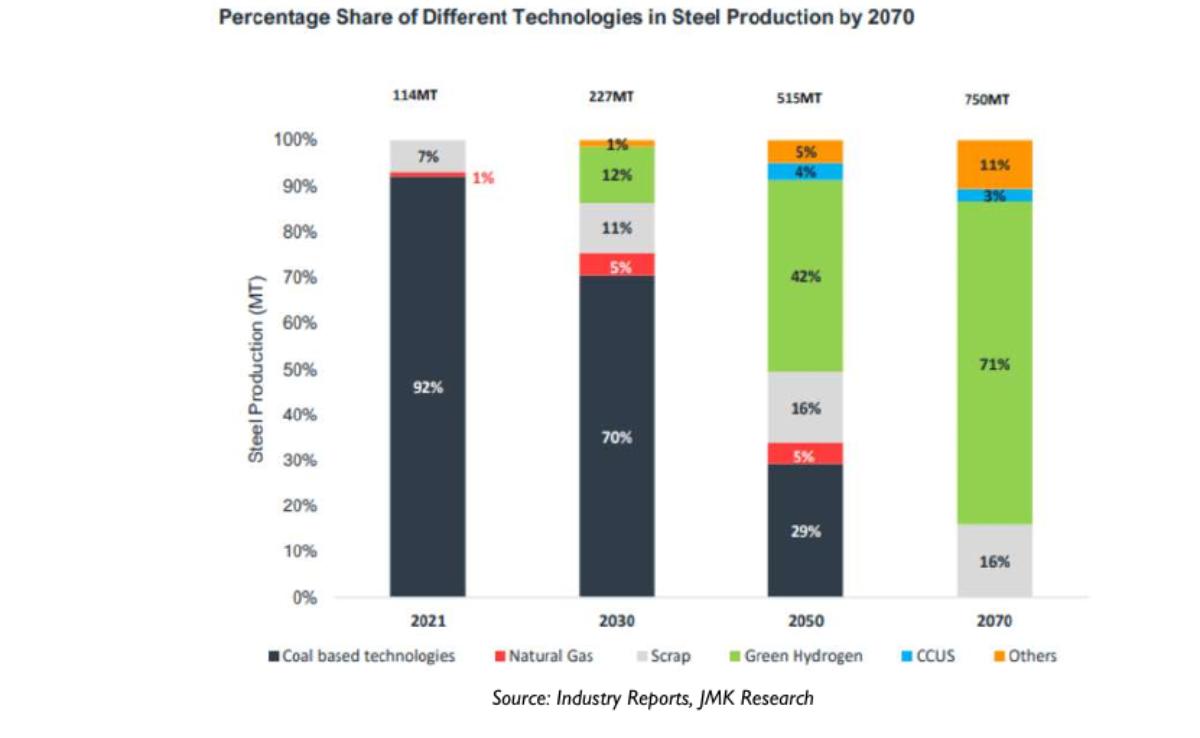

The high emission intensity of Indian steel production is due to existing technologies used by steel plants such as Blast Furnace (BF)/Basic Oxygen Furnace (BOF) or Direct Reduced Iron (DRI)-Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) and scrap-based Electric Arc Furnace (EAF). These are coal based technologies leading to high emission. Currently 92% of steel production in India is coal based. However, India is committed to decarbonise the steel sector by replacing coal based technology with Best Available Technologies (BAT).

The government of India has set an ambitious target for the steel sector to reduce its carbon emission intensity from 2.64 t CO2eq/tcs in 2020 to 2.4 t CO2eq/tcs in 2030 as part of its sector specific contribution to India’s NDCs[14]. By adopting the best technologies in the sector, India has reduced its emission intensity from 3.1 t CO2eq/tcs in 2005 to 2.64 t CO2/tcs in 2020. During this period Indian steel plant adopted technologies such as Coke Dry Quenching (CDQ, Sinter Plant Heat Recovery, Bell Less Top Equipment (BLT), Top Pressure Recovery Turbine (TRT), Pulverized Coal Injection (PCI) system in Blast Furnace, Hot stove waste heat recovery, Dry type Gas Cleaning Plant (GCP) etc.

While India has made efforts in the last few decades to seriously reduce its carbon emission intensity in the steel production, it is still very high in the world. India’s steel may find it difficult to compete in the European market after roll out of CBAM due to its high carbon emission intensity. Despite several technological innovations, the steel production in the country remained coal based. The Long Term- Low-carbon Development Strategy (LT-LDS) adopted by the government of India in 2022 acknowledges the high carbon footprint in the steel production due to dominance of Blast Furnace-Basic Oxygen Furnace technologies used by steel plants which use coke, coal and oxygen.

| Steel Sector Decarbonization Plan of India | |

| Phase – I (2022 to 2030) | Phase – II 2031 to 2050 |

|

|

Source: NITI Aayog, Government of India

The strategy paper of the Government of India is eager to adopt cleaner technologies in steel production such as Hydrogen based technology and HIARNA technology which is being developed under the ULCOS program. However, these technologies require international commercial collaboration and technology transfer[15]. The report of IEEFA also suggests replacing coal based technology with green hydrogen to substantially reduce its carbon emission intensity[16].

A report of NITI Aayog in 2022 prepared a phase wise de-carbonization plan for the steel and iron sector for India. It has proposed three phases to work with hard to abate sectors like steel and iron. In the first phase it proposes to work with existing available technology to enhance energy and emission efficiency. The second phase of steel de-carbonization will start from 2031 and end in 2050. The success of this phase is solely dependent on the use of green hydrogen as fuel for blast furnaces and DRI[17]. The third phase will start in 2051 to sync steel production efficiency with India’s net zero commitment by 2070.

The IEEFA report suggests that the real reduction in carbon emission intensity of India’s steel will depend on replacing coal and coke with green hydrogen as fuel. However, various reports and plans of the government of India suggest that green hydrogen technology requires more time and effort to be utilized in steel plants in India. The Low Carbon Development Strategy of India released by MoEFCC in 2022 acknowledges that green hydrogen production requires international commercial collaboration and further research. The NITI Aayog report in 2022 expects its trial and application only after 2031.

Nationally Determined Contributions Hard to Achieve for the Steel Sector

The Paris Agreement adopted by parties at the UNFCCC in COP-21 held in Paris, France in December 2015 is a legally binding document on all its 196 member nations. The ultimate goal of the Paris Agreement is to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 degree Celsius above the pre-industrial levels. The agreement further encourages parties to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 degree Celsius above the pre-industrial level[18].

To measure the effort and result of the Paris Agreement, the UNFCCC has mandated all parties to submit a national climate action plan called the Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC). The agreement is being implemented in cycles of five years, where each party has to update its NDCs after every five year by setting more ambitious targets compared to the previous cycle.

India being a proactive party of convention submitted its first NDCs in 2015 itself. Its first set of NDCs was as follows:

- To reduce the emissions intensity of its GDP by 33 to 35 percent by 2030 from 2005 level; and

- To achieve about 40 percent cumulative electric power installed capacity from non-fossil fuel-based energy resources by 2030.

In August 2022, India updated its NDCs and set even more ambitious targets. As per the new NDCs, India aims to reduce emissions intensity of its GDP by 45 percent by 2030 from 2005 level. It has further enhanced its commitment to install non-fossil fuel based energy sources from 40 percent to 50 percent of cumulative electric power installed capacity by 2030[19]. The government has claimed that it has achieved previous NDCs well before time.

While India has submitted its updated NDCs in time, it has not specified sector specific mitigation plans to achieve the NDC target. However, the Union Ministry of Steel has revealed its sector specific NDC target on its website. According to the data available on its website the carbon emission intensity of the Indian steel industry was projected to reduce from 3.1 t CO2eq/tcs in 2005 to 2.64 t CO2eq/tcs by 2020 and 2.4 t CO2eq/tcs by 2030 (approximately 1% reduction every year)[20].

The Ministry had banked on adoption of clean and green technology in steel production to achieve above targets. As per data available on the website of the Ministry, the industry as whole had managed to reduce its carbon emission intensity to 2.5 tCO2eq/tcs in 2020. The data from the World Bank suggests that carbon emission intensity of India’s exported steel to EU is 2.01 tCO2eq/tcs. Despite all these progress made in the last 15 years the carbon emission intensity of the Indian steel remains very high compared to its competitors.

The steel and iron sector is hard to abate. Moreover, radical technological transformation is required to adopt clean and green technology. The government of India has itself declared in its long term low carbon strategy paper that it requires international commercial collaboration and technology transfer. India is expecting drastic reduction in carbon emission in steel production only after 2030 by having clean and green technologies. India’s NDC overachievements will not help it to keep its iron and steel export competitive in the EU market.

Conclusion

The Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) rolled out by the EU has the intention to prevent carbon leakages, reduce carbon footprint of EU’s consumption and encourage its trade partners to reduce carbon intensity of their productions. This policy has been widely analyzed from the trade and economic perspective by different stakeholders. But very little emphasis has been given to analyze its impact on global and domestic climate change policies. The CBAM has challenged the fundamental principle of global climate cooperation of ‘Common but Differentiated Responsibilities and Respective Capabilities’ (CBDR- RC) as entered in the UNFCCC treaty document in 1992. The intention of the CBAM is to replace UNFCCC’s equitable sharing of responsibility with equal responsibility sharing.

Challenging the CBDR RC principle of the global climate change policy has wide ramification both at national and international level. A policy like CBAM leaves no incentive for developing countries to bear the burden of reducing GHGs, which has been accumulated largely by developed countries including members of the EU. Moreover, the forceful imposition of carbon price on developing countries is an attempt to interfere in their respective NDCs and long term low carbon development strategy.

The Paris Agreement, 2015 focuses on cumulative effort of parties to reduce emission. Each party with the UNFCCC has designed their NDCs targets in accordance to their local circumstances and developmental needs. However, the CBAM ignores the cumulative progress of a country in reducing emission and focuses on six selected sectors as per their own convenience.

India has announced to streamline all its efforts to meet the target of net zero by 2070. For this, the country has been regularly updating its NDCs for incremental progress and prepared a long term low carbon development strategy for various sectors. These plans and strategies are based on local circumstance and developmental needs of India. However, the CBAM expects from India to suddenly focus on radical de-carbonization of selected hard to abate sectors such as iron, steel, aluminium and cement. This may not yield any result. Moreover, such unwarranted external pressures can affect negotiation instruments for global collective climate mitigation and adaptation.

[1] European Commission, Taxation and Customs Union: https://taxation-customs.ec.europa.eu/carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism_en#cbam-transitional-phase-2023–2026, Accessed on 28 March 2024

[2] Regulation (EU) 2023/956 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 establishing a carbon border adjustment mechanism, https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32023R0956, Accessed on 28 March 2024

[3] The World Bank, World Integrated Trade Solution, https://wits.worldbank.org/Default.aspx?lang=en, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[4] The World Bank, Relative CBAM Exposure Index, https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2023/06/15/relative-cbam-exposure-index#1, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[5] ADB, European Union Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism: Economic Impact and Implications for Asia, Brief No. 276, November 2023, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/928466/adb-brief-276-eu-carbon-border-adjustment-mechanism.pdf, Accessed on 27 March 2024

[6] The Hindu, Feb 26, 2024, India expresses serious concerns in WTO meet over unilateral protectionist measures, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/india-expresses-serious-concerns-in-wto-meet-over-unilateral-protectionist-measures/article67889564.ece, Accessed on 28 March 2024

[7] United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC), 1992, GE.05-62220 (E) 200705, https://unfccc.int/resource/docs/convkp/conveng.pdf, Accessed on 28 March 2024

[8] MoEFCC. (2022). India’s long-term low-carbon development strategy. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India. https://moef.gov.in/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Indias-LT-LEDS-2.pdf, Accessed on 28 March 2024

[9] International Trade Administration, Global Steel Trade Monitory, August, 2019 https://legacy.trade.gov/steel/countries/pdfs/imports-eu.pdf, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[10] The World Bank, Relative CBAM Exposure Index, https://www.worldbank.org/en/data/interactive/2023/06/15/relative-cbam-exposure-index#1, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[11] Ministry of Steel, Government of India, https://steel.gov.in/en/energy-environment-management-steel-sector, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[12] Ministry of Steel, Government of India, https://steel.gov.in/en/overview-steel-sector, Accessed on 27 March 2024

[13] IEEFA, September 2023, Steel Decorbonization in India, http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/Steel%20decarbonisation%20in%20India.pdf, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[14]Ministry of Steel, Government of India, https://steel.gov.in/en/energy-environment-management-steel-sector, Accessed on 27 March 2024

[15] MoEFCC. (2022). India’s long-term low-carbon development strategy. Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change, Government of India.

[16] IEEFA, September 2023, Steel Decorbonization in India, http://www.indiaenvironmentportal.org.in/files/file/Steel%20decarbonisation%20in%20India.pdf, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[17] NITI Aayog, Government of India, Report of the Inter-Ministerial Committee on Low Carbon Technologies, 2022: https://www.niti.gov.in/sites/default/files/2022-11/Report-Committee-on-Low-Carbon-Technologies.pdf, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[18] UNFCC, Paris Agreement, https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement, Accessed on 29 March 2024

[19] PIB, Government of India, 18 December 2023, https://pib.gov.in/PressReleaseIframePage.aspx?PRID=1987752#:~:text=In%20August%202022%2C%20India%20updated,enhanced%20to%2050%25%20by%202030., Accessed on 29 March 2024

[20] Ministry of Steel, Government of India, https://steel.gov.in/en/energy-environment-management-steel-sector, Accessed on 27 March 2024