In the semi-arid regions of South India, tanks and ponds play a very important role in providing water for irrigation, domestic use and drinking water. These water bodies are also essential for livestock, support local ecosystem, recharge of ground water, control of floods etc. However, in the last several decades tank irrigation has drastically decreased due to several socio-economic and institutional factors. PRADAN (Professional Assistance for Development Action) restored few tanks and ponds in the four district of Tamil Nadu. This article is the summary of a full assessment report of PRADAN’s work in Tamil Nadu to restore tanks.

Background

Madurai and its surrounding districts in Tamilnadu have been showing a declining trend in rainfall during the last 30 years. The Northern part of Madurai receives an average annual rainfall of 840 mm while the Eastern part receives a little more at 900 mm. Virudunagar has smaller average annual rainfall of 820 mm. Sivagangai is even drier. These areas receive rainfall during both South West as well as Returning Monsoon, the former contributing about 40% of the annual rainfall. Landscapes in these areas present a somewhat grey picture of almost wasteland like appearance with frequent and large clumps of Prosopis juliflora revalidating their status as semi-arid territories.

Of the 1,53,400 ha. net sown area of Madurai district, close to two thirds is irrigated. Dug wells canals and tanks are the principal sources of irrigation in the district. The stage of ground water development is 62% in the sense that 62% of the replenishable ground water resource is drawn for irrigation and domestic uses. There were 3 Over-exploited blocks in the districts of which 2 were classified as “critical”. In consequence of high withdrawal of water, salinity as well as fluorine levels have been rising in ground water in the district. Central Ground Water Board has cautioned against unbalanced ground water development in this region.

Tanks constitute an important means of water use in agriculture. In fact, their place was eminent in the scheme of things for agriculture before the advent of motorized pumps. Tanks were in general managed through a fairly elaborate social institutional system. Farmers with land in the tank command would together take the responsibility of managing the water distribution as well as the maintenance of the inlet waterways as well as the tank structure. A person appointed to ensure equitable distribution of water, traditionally called “neerkatti” was paid in kind by each of the user farmer giving a portion of his crop output to him. Farmers contributed labour for managing the structure and clearing the inlet water ways. Norms existed regarding the multiple uses of water (animal feeding, domestic use, irrigation, recreational etc.)

Scholars tend to agree that the advent of motorized pumps as well as decline in the social institutions have together contributed to the continuous decline in quality of structures and the inlet water course, reducing the quantity of water stored and thus reducing the irrigation potential. This was done because those farmers who wielded power in earlier times were the first to acquire pump sets to exploit then reasonably abundant ground water, used it through formal or informal water markets and thus gained both relative independence form the tanks systems as well as power over other farmers. Yet as the topography and rainfall pattern suggests, tanks do occupy an important place for several farmers. Today one may say that in almost equal measure they support drinking water security, ground water recharge and crop irrigation. Efforts have been under way in several locations to mobilize the community to try and restore the tanks, clear the water way so that they get filled up and revive the system for equitable use of the tank water across different user groups. In fact, tank restoration has become an important program in the civil society world as well as development administration.

The Project:

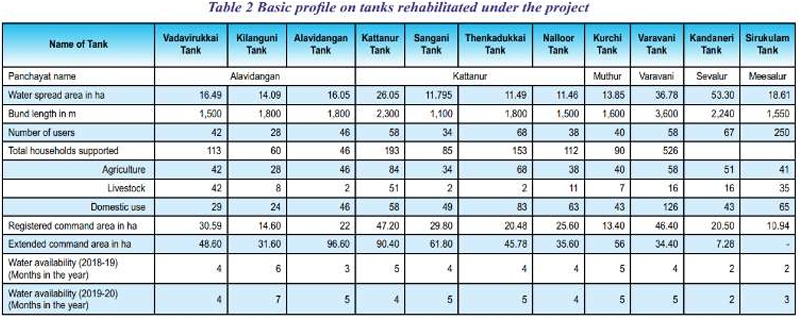

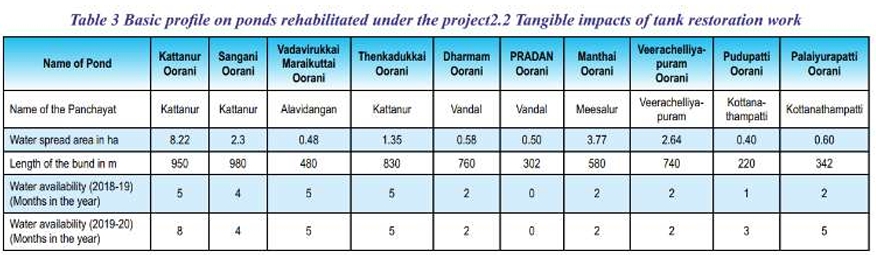

Looking at the criticality of water to the very life of people here, Interglobe Aviation had financially supported PRADAN to undertake restoration of tanks and ponds in Madurai and Virudunagar districts. PRADAN was expected to restore 8 tanks and 10 ponds. The restoration was aimed at increasing the quantity of water stored and available in each tank / pond, to make critical irrigation available to the farmers in command area of these structures, to promote tree plantations on tank bunds, and also to include landless community by encouraging fish cultivation in the water bodies. The tanks and ponds were expected to be seen and used by the communities as multiple-use water structures combining irrigation, fishing, recreational and domestic uses.

Under the project, cumulatively, over 240 ha of water bodies have been restored benefitting over 650 farmers in growing their crops and has benefitted over 3,500 households through other routes such as domestic use, livestock watering etc. Given that the total money spent has been a little over a crore, this is a huge achievement. This has been made possible by mobilizing the communities, by creating awareness about the possibility of restoration and a willingness to work towards it among the community members. The communities have contributed towards these works. In one place Vandal, over 1.8 ac of land owned by several households was donated to the community for creating a new pond. Virtually every tank restoration task had community contribution in cash, in terms of some labour as well as in kind by providing stones and sand where needed.

Tangible impacts of tank restoration work

- Farming: Paddy is the most popular field crop in this region and people depend on irrigation for growing paddy as it is a rain deficit area. All registered users always press for obtaining water for growing paddy. Restoration of tanks has made it possible to supply water to farmers. Here are a few examples from our field observations.

Vadavirukkai: farming has been under severe water stress since 2014-15. No rabi crop was cultivated in the last five years before the rehabilitation work taken up by PRADAN. The inlet channel was in a veery bad shape due to siltation and encroachment blocking the inflow to the tank. As part of the project, the inlet channel of about 2 km was revived, of this 1.1 km is retrieved from encroachment and excavated to its fullest width.

This brought a very good amount of water into the tank which is lasting through the year. The tank has not gone dry since the rehabilitation work. Over 40 farmers have gone for rabi crop during the last two years. Further, they were mentioning several farmers downstream were able to get some residue water due to the availability of surplus water in the tank. Cotton crop during rabi season during last year fetched them a very good production with about 4 quintal of cotton per acre. This has resulted in increase of income by a very substantial sum. Some farmers reported income increase by about Rs. 3 lakhs.

Sevalur: Farmers in Sevalur depend on Kandenari tank for farming. Almost all the farmers were in huge distress as they could not cultivate even one crop for last 3-4 years due to lack of enough water in the tank to do cultivation. Though the village has 26 open wells, many of them are not in functional condition. Less than 10 farmers with functional wells were able to cultivate a limited portion of their land. Some of the land that use to be under cultivation were also infested by invasive Prosopis as they were left fallow for several years. Deepening of tank and rehabilitation of supply channels rejuvenated the tank and helped all the farmers in the village to go for cultivation. Farmers invested about 10,000 per acre to clear the Prosopis infested land and bring them back under cultivation. More than 70 acres of land were cultivated with paddy with yield range of 20-30 quintals per acre resulting in income of about 30-50,000 per acre.

Kattanur: Kattanur tank is one of the big tanks in the region with the water spread area of about 250 acres. The government spent over 20 lakhs, just two years back to rehabilitate the tank and they did not do the channel work. The supply channel is not excavated to its fullest length, width and depth in the last fifty years and more. In the last thirty years the encroachment has been detrimental to the tank. Though the supply channel is several kilometer in length, PRADAN excavated around 1 km upto the village limit due to fund limitations. But this has by itself proved very effective in bringing water to the tank that is lasting till now. Similar to Vadavirukkai village, the farmers were not cultivating rabi for several years due to unavailability of water. The rehabilitation work in the supply channel helped the revival of the tank. The water is still available in the tank and the farmers have cultivated second crop this year.

Drinking water: When tanks retain water, they also ensure that dug wells have water. This helps farmers for drinking water. Once the tank dries up or has no water, wells too go dry and are not able to provide drinking water. Drinking water is the everyday need of every household. Tank restoration has helped the villages in this regard as well.

Vadavirukkai: The community depends on a well located in the tank close to supply channel for their drinking water. Due to siltation and encroachments, the supply channel was defunct and the well-used to go dry at the start of summer. Drinking water issues were rampant two year ago. All the households were forced to rely on tanker-based drinking water supply which would cost them upto Rs.3,000 per month. Rehabilitation of supply channel and the tank deepening around the well has ensured that well get recharged effectively. Now, the people are confident that their well has enough water to take them through till next monsoon. Further, the continuous presence of water in the tank has also improved the quality of water in the well by decreasing the salinity of water in the well. Water gets pumped to an overhead tank near the village for getting distributed to the households. Further, the drinking water pond in the village was also rehabilitated by deepening and creation of new supply channel inlet pipe. Though the water appears to be muddy, villagers use a traditional method of using a plant seed to obtain clarified water.

Vandal: This pond has been constructed from the scratch by the PRADAN team and community. Though this hamlet had a tank bund close to their settlement, unlike most villages in this region they did not have exclusive drinking water pond. It has been an aspiration of the village for a very long time to build a drinking water pond for their hamlet. Though PRADAN team did not encourage or support the idea of building a new pond, persuasion of villagers over several meetings and their collective will convinced PRADAN to take up this work. Since there is no common land available to construct the new pond, 21 villagers with their land close to the field channel offered their land spread of about 1.8 ac for building the new pond. The construction has been recently completed and named after PRADAN.

Pazhaiyurpatti: Though the village has couple of drinking water schemes and piped water connection, they are either not reliable or expensive for many households to completely depend on it. The drinking water pond is dependent on Periyar-Vaigai canal for water replenishment. The pond became shallow with weak bunds. Villagers came together to rehabilitate the drinking water pond with the support of PRADAN. Though the funds were limited, community contribution and presence of excavator in the village and his volunteering made it possible to rehabilitate the pond. Soil is rocky and PRADAN team considers this pond work as one of difficult earthwork they have done and community volunteers played a significant role in it. Though some water used to be available before the project, the supply use to be limited. Women in village prefer to use water from this pond for cooking. They consider this water to give them tastier food and also reduces their body ailments. With respect to economics, the RO water supply comes at a price of Rs. 4 per kodam (a pot with about 10 litre capacity). On an average, most household consume one pot from RO water supply for every two days and two pots daily from the drinking water pond.

Environment: While the benefit of water to farming and households are relatively tangible, ecological services like impact of rejuvenated water bodies on presence of bird population. A study by Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS) along with PRADAN indicates a presence of over 92 species of birds, of which 16 are migratory species from Arctic and Himalayas and the rest local migrants, across three adjoining tanks Sivagangai. Though we do not have expertise in this subject, we sighted over 20 varieties of birds during our field visits.

Fisheries: Fishing has been a huge value addition for the villagers. Traditionally the fish harvest happens as a community activity during the summer when the tank is about to run out of water. The event has some basic rules in the methods and means you catch and all the catch you have is for your own. As the water in the tank reduces, an auspicious date is fixed through a village meeting and announced. This event is like a festival where the villagers invite their relatives and friends for the event. Kandeneri tank in Sevalur is very popular for this event. However, there are few tanks where the fish harvest is sold on bid and the community group will be paid for the same. Often, the value of fish harvested and the returns through the bid are not shared with outside people. Since PRADAN had introduced several thousands of fingerlings in each of the water bodies covered under the project, it was estimated that the community will get a harvest in the range of 4 – 15 tonnes depending upon the tank. This could fetch them upto 5 lakhs.

Livestock: Livestock plays an important role in the livelihood of the farmers. Production of milk and presence of cooperative milk procurement units makes the dairy farming viable and regular source of income. Similarly, market for meat is also lucrative and hence a large population of small ruminants is also visible. Tanks and ponds are the key source of water for the livestock. While there are prescriptive rights for the tank water to be used for agriculture, usually there is no restriction on livestock consuming water from a tank. Villagers do not prohibit the herders from different villages to rear their livestock and drink water from their tank. Similar to purchase of drinking water for the households from private tankers, villagers pay about Rs.2-3 per pot of water for their livestock during summer when their tanks go dry. This has been the situation for the last 4-5 years. Rehabilitation of tanks has a double fold impact on livestock where ample water in the tank ensures healthy and productive animals and cuts down the expenditure on purchase of water for animals.

Other impact of the project

Community’s Technical knowledge: Villagers consider that their traditional knowledge on tanks and ponds has been dwindling and the current younger generation are not aware of most of their cultural practices to safeguard and revive the water bodies. PRADAN team has been working in the subject in similar regions for past several decades and is pioneering the technicalities of these water structure. Their implementation design is bringing the people closer to science behind the water structures. The disconnect of communities with that of science behind chain of tanks is getting reduced with increasing participation of the community in design, implementation and maintenance of the water structures.

Attention received by communities: The project activities have got significant attention from media and as well as the government bodies for several reasons. The first reason is the effectiveness of the intervention in addressing the water issues and the second reason is the level of participation from the community in implementing the rehabilitation work. Many of the project activities has been reported by local and regional media outlets. Further, the project work has grabbed attention of various bureaucrats and government engineers as they have all been implemented in half or less than half of the budget of similar rehabilitation works they have carried out in the same region. In some villages, people were proudly sharing that their work which is part of the project has become a benchmark and several officials from district administration keep visiting the site for learning.

Social capital: Progressive villages with relatively lesser conflicts among the villagers tend to respond better in terms of participation and ownership of rehabilitation of water bodies. As discussed in the earlier section, unity among villagers becomes the core for a successful rehabilitation work.

Endless demand: In most cases, villagers have their untold aspiration to revive the water bodies in their village. However, neither there is any engagement of community in government-initiated rehabilitation nor the villagers trust and participate in most of the government initiatives. PRADAN team over the years appears to have earned their trust and villagers are quick to respond and participate. A trigger to the aspirations of the villagers followed by technical and legal guidance and facilitation of balanced participation imparts ownership among the villagers results in higher probability of impactful and sustainable rehabilitation of water bodies.