The Indian economy is growing at a 7-year-low GDP growth rate. It was 4.7 per cent in October-December 2019.This revived to about 5% of GDP – the lowest in six years.The economy is anticipated to further shrivel as a result of the slump in manufacturing as well the spread of coronavirus globally. Fitch Solutions also presented a dismal picture of economic recovery for India. Moody’s has cut projected growth from 5.4 per cent to 5.3 per cent for 2020, as the spread of the virus will reduce domestic demand globally. Additionally, Moody’s also anticipates an ‘extensive and prolonged slump’ in case of further increase in coronavirus cases or public fear leading to confinement. In the predicted scenario, Moody’s expects India’s growth to fall to 5 per cent in 2020

Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) data shows that manufacturing sector growth declined from seven-year high of 55.3 in January to 54.5 in February.18 out of the 23 industry groups in the manufacturing sector experienced negative growth during the month of October 2019 as compared with the same period last year.Activities of eight core sectors have fallen to 2.1 per cent in August 2019, sharply declining from 7.3 per cent in the corresponding period a year ago.

Bank credit growth dropped to 8.5 per cent in January compared to 13.5 per cent January 2019. This could be a result of slowdown in industrial growth or hesitancy of lending by banks due to the credibility of repayment.The automobile sector is also facing significant slump in sales, on account of decline in demand.The overall auto industry reported a decline of 23.55 percent in August 2019 while the passenger vehicle segment declined by 3 1.57 percent in the month. In real estate, over 1.3 million houses worth about 5 percent of GDP are lying unsold across India.

GST collections have fallen beneath the monthly target of $14 billion, this may lead to the Government breaching the deficit target of 3.3 percent in March 2020. Investment demand shrank by 4.1 per cent in the September 2019 quarter and by 5.2 per cent in the December 2019 quarter. The MSMEs have also been hit.The disinvestment of Air India looks bleak. Auctions of toll roads, coal mines or railway routes will attract much lower bids.

Several factors are causing the current lower demand for goods and services such as declining rural wages, stricter lending norms and rising unemployment. Structural factors also contribute to the sluggishness. On the supply side, excess idle production capacity, weakening corporate profits, and infrastructure bottlenecks have slowed down investment in production facilities and hiring. At the brink of a demographic dividend, the depression across manufacturing, automobiles, real estate and MSMEs points towards a severe economic pressure and constraints for jobs. The alarming levels of youth, women and graduate unemployment portray an acute deficit of jobs for the productive bulk of the population.

A study by CARE highlights the job creation in India grew to 3.9% in 2017-18 and 2.8% in 2018-19. Among the core industries there has not been any growth in employment while the oil sector has just about been maintaining the employment levels in the country. The country needs to be growing at between 8-10% a year to accommodate the million plus workforce, however Indian growth is seemed to be hovering around 5%. Given the rising unemployment, weak manufacturing, low auto sales, and the declining GDP growth rate consumer spending will most likely witness further slump as a continued process.

It is noteworthy that the Economic Survey 2019-20 had proposed that India can create well-paid four crore jobs by 2025 and eight crore by 2030 by integrating “assemble in India for the world” into government’s Make in India initiative and exporting network products that can give substantial push to India’s target of becoming a $5 trillion economy. Indian government decided to give out corporate sops and restructure banks in a hope to jump-start economic growth. However, in estimates by International Labour Organisation, about 81% of India’s workforce is in the informal sector whereas only 6.5% is formally organized workforce, a slew of reforms may not impact the non-formal economy, accounting for 85% of India’s GDP.

Downturn in the Global Economy and its effect on India

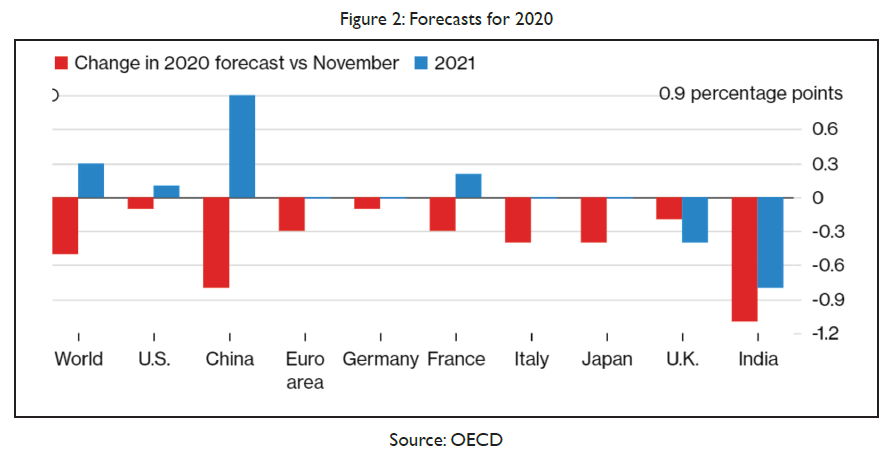

In backdrop of the coronavirus outbreak, annual global GDP growth is projected to drop to 2.4% in 2020, from a 2.9% in 2019, with growth possibly even being negative in the first quarter of 2020, according to the latest estimates by IMF. As the global economy has become significantly more integrated, China being at the epicenter of global output, trade, tourism and commodity markets, spillover shocks to other countries is inevitable

The trade impact of the coronavirus epidemic for India is estimated to be about 348 million dollars and the country figures among the top 15 economies most affected as slowdown of manufacturing in China disrupts world trade, according to a UN report. China accounts for 20% of the world’s manufacturing output, the economy is also facing a fall in consumption demand. This is going to produce extremely large repercussion as the country is responsible for 15% of the global demand.

While this might be a good place for India to occupy the manufacturing space as well exploit the eased commodity prices, Indian industries such as fertilizers and pharmaceuticals are heavily dependent on supplies from china. Any disruption in the supply could cause much turmoil in India. A supply disruption could shoot up the prices of drugs. In India, the prices of paracetamol, have surged 40 per cent, while the cost of azithromycin, has jumped by 70 per cent. As China is India’s largest trading partner , India may have to look for substitute markets in case the outbreak prolongs to a longer duration.

The pandemic of coronavirus is forcing Governments to put countries under lockdown and waive mortgage payments. Travel, trade, transport, and tourism are taking a backseat. Schools and universities are closing, meetings are being cancelled. Inactivity will result in a huge demand deficit as well as supply shocks. This will lead to a large dent in production and subsequent disruption in global value chains.

The ongoing crisis between Russia and the OPEC (Organisation of the Petroleum-Exporting Countries and the failure to stabilize oil prices, has led to oil prices plummeting to new lows.The continued fall in prices will result in oil companies getting bust. Drilling and other activities will plunge, and many suppliers will not get paid by collapsing companies. This will exacerbate the problem of assets (NPAs) in the banking sector.

India’s import bill falls by Rs10,000 crore for every dollar drop in oil price. It could imply gains for India. However, remittances from, and exports to, the Gulf will essentially see a decline.The US Federal Reserve will respond with more liquidity and interest rate cuts, however it may not uplift sentiments in a virus-effected economy.

Global economic outlook is further dampened by ongoing trade and investment stresses as well as uncertainty over Brexit. In 2019, global trade contracted due to the trade war between the United States and China. Overall trade volume was down 0.4 percent from 2018.Trade decline leads to disruption industrial production and investment , leading to slower economic growth.

Interventions by the Government could include fiscal support for health services, flexible work regimes with guarantees on take-home pay, providing liquidity to the financial sector, targeted support for affected industries like tourism, and looser state aid and fiscal rules.

Is the average Indian getting a lower real income?

The latest government data that has been leaked out suggests that poverty in India seems to have gone up in recent times. Another survey shows that unemployment has gone up like never before. It is also possible that the government’s claims that Indians have started using toilets are grossly exaggerated. The reason for this distrust is the fact that for the first time ever in independent India the government is refusing to release data on poverty and employment. Last year, before the parliamentary elections, the results of the Periodic Labour Force Survey were not allowed to be released until the Parliamentary Elections were over. Subsequently, results of other surveys including the 75th round (Consumer Expenditure), 76th round (Drinking water, Sanitation, Hygiene, and Housing Conditions) and more recent quarterly data of the PLFS surveys, have not been released.

What is the government worried about? It is so clear that the economy is in a bad shape. India’s factory output shrank by 4.3% to the lowest level in eight years in September, because of a sharp fall in capital goods production. Industrial production is likely to continue to struggle more in the coming months. Eight core infrastructure industries, declined 5.2% in September from a year ago — the steepest drop in 14 years.A contraction in production in sectors like coal, steel, electricity and natural gas meant overall demand was weak. As a result there are huge job losses in the country.

Usually sales pick up during Diwali, in October, when shoppers usually spend on food and gifts. This year, festival sales were relatively subdued. More than 90% of storekeepers indicated footfalls were lower than last year, according to research by Bank of America Merrill Lynch analysts. Car sales fell 6.3% in October from a year ago — the 12th straight month of decline — after plunging 33% in September, according to data released by the Society of Indian Automobile Manufacturers.Two-wheeler sales were down 14.4% from a year earlier while demand for trucks and buses were down 23.3%. Growth in bank credit has slowed to around two-year lows amid sluggish demand from companies.

Private sector investment, the mainstay of sustainable growth in any economy, is at a 15-year low.In other words,there is almost no investment in new projects by the private sector. The situation is so bad that many Indian industrialists have complained loudly about the state of the economy, the distrust of the government towards businesses and harassment by tax authorities. But India’s economic slowdown is neither sudden nor a surprise.This is despite the fact that the government, led by the Prime Minister has been announcing that the India economy is the fastest growing in the world with record levels of foreign 9nvetsment coming in.

Behind the fawning headlines in the press over the past five years about the robustness of India’s growth was a vulnerable economy, straddled with massive bad loans in the financial sector, disguised further by a macroeconomic bonanza from low global oil prices. India’s largest import is oil and the fortuitous decline in oil prices between 2014 and 2016 added a full percentage point to headline GDP growth, masking the real problems. Confusing luck with skill, the government was callous about fixing the choked financial system. This inability to clean up the banking sector coupled with unwise moves like demonetization, ensured that the India economy started to weaken and quickly went into a downward slide.

The government, instead of owning up and analyzing the causes of the downward trend, has reacted by refusing to share the data.This is a typical mistake made by those who refuse to look at reality.This attitude of not allowing data to be published also puts the government in a defensive position when tackling questions about the fall in consumer demand that is so visible. It also ensures that the state does not have the available information to take corrective steps.

The last time there was controversy regarding data was when the Vajpayee government had released the results of the 55th round of the NSSO that showed that poverty had fallen significantly in the country. This data was sharply contested by all economists and was shown to be incorrect. However, at that time, the government did not hide the results nor did it refuse to share the data. It is only now that the India government is hiding behind spurious excuses and not sharing data that is showing that the economy is on a decline.

A quick reading of the leaked findings makes it amply clear that the real reason for withholding the release of the report is the revelation that real consumption expenditure on comparable measure has declined between 2011-12 and 2017-18, a large part of which is the period when this government has been in power.According to the leaked report, real consumption expenditure declined by 10% per annum in rural areas and increased marginally by 2% per annum in urban areas, with an overall decline of around 4% per annum for the country as a whole which in simple terms means that the Indian consumer has lesser money to spend and is therefore earning lesser that he was in previous years.

The immediate implication is that poverty levels would, in all likelihood, have increased between 2011-12 and 2017-18, as against a sharp decline between 2004-05 and 2011-12. It is this uncomfortable truth that the government did not want to come out at a time when the hype has been that everything is well with the economy. The PM has been claiming that the economy has been growing at a fast clip and inviting foreigners and NRIs to invest in India.The data that it is hiding now would indeed be very embarrassing and that is why is being denied.

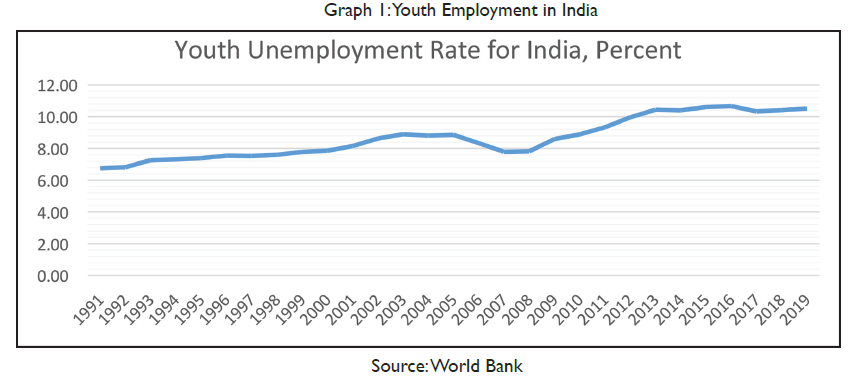

Youth Employment in India

The big problem with looking for solutions to development challenges in India is the lack of credible data. What underlines India’s poor performance recently is the absence of any trust in Indian data. The government has been accused of either tampering with data that does not suit its narrative or in plainly refusing to divulge data that points towards unprecedented unemployment rates. The absence of data hurts the entire market and when data is not available, the estimates used are very suspect and can lead to erroneous business decisions leading to huge amounts of unsold inventory and associated carrying costs. The automobile sector is struggling on account of millions of unsold cars and motorcycles.As is the construction sector where apartments and houses stay unsold for months. The biggest problem however is that data on unemployment is either missing, doubtful or simply not being collected.

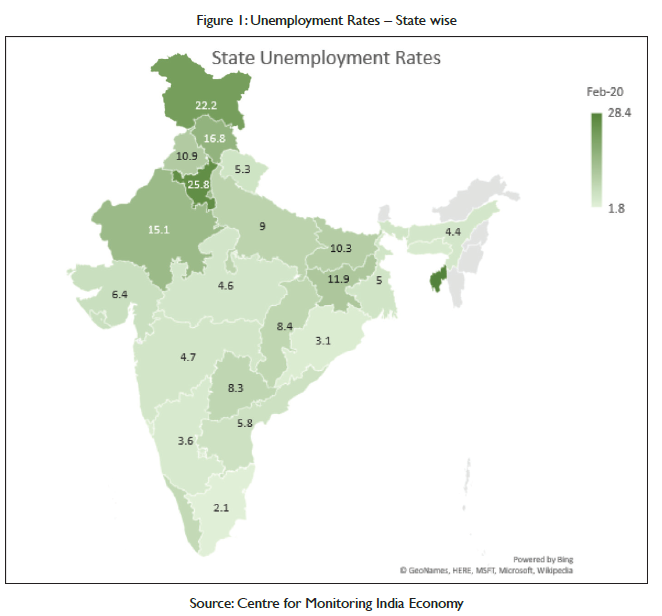

Therefore we have various estimates.About 5 million Indians will be entering the workforce this quarter and new jobs will need to be created.The educated workforce will require jobs in the organized and formal sector.According to the data presented by Trading Economy the unemployment rate as of February 2020 was 7.8 percent.The number of people estimated to be employed fell by 5.5 million, from 411.3 million or 39.9 per cent in January 2020 to 405.8 million or 39.3 per cent in February 2020. The unemployment in India has averaged at 7.34 percent from 2018 until 2020.Trading Economics predicts unemployment to trend around 6.40 percent in 2021 and 6.60 percent in 2022. The current unemployment rate is said to be the highest in the last 45 years.

The Periodic Labour Force Survey data for 2019 pegs the unemployment rate in urban areas as 9.3 per cent in the first quarter of 2019, down from 9.9 per cent in the last quarter of 2018 and lowest in a year. For people aged 15 years and above, this figure was 9.2 per cent, down from 9.7 per cent in Q4 2018. And for the youth between 15-29 years, unemployment rate was 22.5 per cent, compared to 23.7 per cent in Q4 2018. A fifth of the youth remain unemployed. The total number of workers in the economy was 472.5 million in 2011-12, which fell to 457 million in 2017-18. The absolute number of workers declined by 15.5 million over six years.

Another alarming fact revealed by the data is the falling female labour force participation and rising female unemployment.The female LFPR remains between 16-17 per cent, which means only every sixth woman is even seeking employment. In the first quarter of 2019, the LFPR for women was 15 per cent (all ages) as against 56.2 per cent for men. In the ages between 15-29 years, it was 16 per cent, versus 57.9 per cent for men.

Data brought out by Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy shows that urban unemployment was at 9.7 per cent in January 2020.Youth in the age group of 20-24 years reported an unemployment rate of 37 per cent while graduates in the same age group had an unemployment rate of 60 per cent.

The decline in employment could be attributed to reduction in agricultural workforce as well as a fall in the numbers of women workers. 37 million workers left agriculture in the last six years possibly due to the increasing crisis in agriculture. About 25 million women workers were out of the workforce.

The Economic Survey suggested China-like labor-intensive economic growth. The Budget 2020-21 will provide for INR 993 billion for the education sector and INR 30 Billion for skill development.The budget also included an infrastructure push which aims to boost GDP growth and employment.

Migration in India – Boon or Bane

The Economic Survey of India 2017 estimated that the magnitude of inter-state migration in India was close to 9 million annually between 2011 and 2016, while Census 2011 pegs the total number of internal migrants in the country (accounting for inter- and intra-state movement) at a staggering 139 million. Inter-state labour mobility averaged 5-6.5 million people between 2001 and 2011, yielding an inter-state migrant population of about 60 million and an inter-district migration as high as 80 million. Between 2001 and 2011, the rate of growth of labour rose to 4.5 per cent per annum, double the previous decade. The acceleration of migration for females was twice the rate of male migration in the 2000s. There was also a doubling of the stock of inter-state out migrants to nearly 12 million in the 20-29 age group.

According to the Census of 2011, 45 million Indians moved outside their district of birth for work opportunities. However, just 5 out of 640 districts in 2011 accounted for 15% of all migrants who moved in for employment.These were Thane (1.6 million), Bangalore (1.5 million), Mumbai Suburban (1.3 million), Pune (1.2 million) and Surat (1 million). 57 districts with employment opportunities across India saw more than 20% of migrants moving in for work reasons.

About 196 districts see less than 5% of in-migration movement, these being primarily of UP and Bihar. On the contrary, Uttar Pradesh (3.8 million) and Bihar (2.4 million) accounted for 47% of all migrants moving out for work reasons. Only 25% of migrants who changed states did so for work. Only 8% of intra-state migrations were for work and employment. 2% (of the 68% women migrating) of migrant women moved for work, as opposed to 26% of men. 3/4th of work migration is to urban areas.

The growth of livelihood opportunities coupled with reduced risk and costs of migration have led to an unprecedented increase in level of migration. The availability of social security schemes and overcoming language constraint has eased the risk of migration.The fact that internal migration rates have dipped in Maharashtra and surged in Tamil Nadu and Kerala, reflect that language no longer acts as a barrier.

Migration is known to boost income and investment; it also serves as a safety net for poor rural areas. Migrant labourers are mostly employed in the unorganised sector, making them vulnerable. In 2001 and 2011, the proportion of migrants who settled in the urban periphery versus those who settled in the urban core was greater for the urban agglomerations of Hyderabad, Chennai, Kolkata and Mumbai. However, in Delhi and Bengaluru more migrants settled in the urban core, rather than the peri-urban. Owinf Caste and religion-based residential segregation in cities, migrants to move to the peri-urban areas where the price of exclusion is at least lower.

The archaic law of Inter-State Migrant Workers Act, 1979 is the only act which aims to safeguard migrants. Lack of data hinders policy making and regulation of migrants. The economic survey highlighted the need for Portability of food security benefits, healthcare, and a basic social security framework for the migrants and need for coordinated inter-state efforts on managing the fiscal costs of migration.

Migration in India follows a typical pattern. It occurs as a result of regional disparities in income and wealth. Migration is largely directed to urban or a semi-urban areas.While regions like National Capital Region in North India — Delhi, Gurugram, Gautam Budh Nagar witness large-scale in-migration, under-developed regions such as Bihar witness a net out-migration. Dominant populations of migrants are comprised of youth who move out for better jobs and education. Women migrate more as a result of marriage rather than for work opportunities. Intra-state mobility remains extremely high in the migration patterns. As migration will lead to large influx of migrants in urban areas consumer spending and sectors like automobile , housing and apparels may receive a boost.

Needless to say, the economic situation of migrant workers is the bleakest. Most of them not only lost their jobs but were packed off from work related staying places.With trains and buses stopped, many had to pay several moths savings to barely get home and others had to walk back home. And when they got back to the village, they received a hostile reception due to the fear that they may be carrying the virus. In any case, there was little or no paid work in the village back home. So how to manage?