Introduction

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), a regional grouping comprising Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, is now 35- year old. As per the SAARC constitution the organization should already have held its 34th Summit and been preparing for the 35th. Curiously, however, it has not yet been able to formalize its 19th Islamabad Summit of November 2016. On the question the organization is caught in a technical bind. In the 19th ‘Summit’, barring Nepal, the then SAARC Chair, all the remaining six members had abstained in deference to India’s fury against Pakistan’s massive terrorist attack in J&K’s Uri town in September 2016, not even two months prior to the Summit. Against this background what sense one makes of the supposedly ‘held’ Islamabad Summit? On the one hand, Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif had ‘addressed’ the Summit, which means that the Summit was held; and yet on the other hand, he had ‘postponed’ the Summit, which means he himself meant to announce that the Summit was not to be officially recognized. He had declared that the new dates would be announced soon which has not been done so far. In short, SAARC is a lame duck now.

Theory of Regionalism

There must be something fundamentally wrong with the organization because for it is not for the first time that an annual meeting could not be held on time. The phenomenon has become the norm rather than an exception. Going by regional theory SAARC is a conceptual oddity. Its contradictions were evident even in 1985 when India and Pakistan, its two leading members, had celebrated its birth rather unenthusiastically. They would probably have been happier had the baby not been born at all. However, since other smaller nations in the region were keen about it, neither of them wanted to give the impression that it was the villain of the piece. They did join the grouping yet continued to remain vigilant about each other’s moves so as not to be caught on the wrong foot. Over the years these suspicions have become sharper, and, contrary to the expectations of smaller nations, the SAARC forum has provided them with yet another opportunity to wash their dirty linen. To complicate matters, China, the elephant in the room, has exacerbated the contradictions which smaller member-nations, Pakistan in particular, have taken full advantage of to neutralize India’s natural preeminence in the region.

Two basic handicaps plague the SAARC, one, strategic incongruity, and two, power asymmetry. No major regional organization in the world suffers so much from these limitations. During the Cold War, nuances notwithstanding, India was seen as pro-Soviet while Pakistan, pro-American. In the post-Cold War period, while India managed to improve its equations with the United States the China factor got further entrenched, Pakistan playing its China card more stridently to the detriment of India’s power projection in the region and beyond. India indeed has made up its relations with China over the years, which now has become India’s biggest trading partner, but the ghost of India’s 1962 defeat in its China war haunts the Indians till this day. Unsettled border issues routinely prick India’s sensitivities to the glee of most of India’s neighbours, Pakistan in particular. The fact that both India and Pakistan are now nuclear powers have added to the anxiety.

So far as regional asymmetry is concerned, prior to Afghanistan’s entry into SAARC in 2007, in terms of size, population, GDP, military strength, and share of the region in global trade, India accounted for almost three-fourths of the region. Afghanistan’s inclusion somewhat changed the territorial reality but not in respect of other parameters. If this is compared with other regional organizations like the European Union (EU), African Union, Agadir (free trade agreement among Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Tunisia), or ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) it would be seen that India towers over its neighbours as obtaining in no other grouping. The only exception was NAFTA (now defunct) in terms of certain critical parameters. But, unlike SAARC, America was indisputably the predominant constituent of NAFTA. In the first place it was a superpower and secondly there was no China-type factor influencing the organization. In no way could Canada or Mexico to play ball with Washington. In all practical sense there was strategic congruity. Canada and Mexico could ill afford the luxury of pricking the U.S. strategic sensitivity. Although Mexico’s membership in NAFTA did annoy its neighbours like Bolivia, Uruguay and Venezuela, the economic advantages of its American partnership far outweighed those pinpricks.

Baggage of History

From the day India and Pakistan came into being in 1947 over of the ruins of the British Indian Empire the two nations have been at their daggers drawn. Generally it is argued that this conflict emanates from the two fundamentally contesting theories of their nation-building strategies, namely, a two-nation theory versus a composite India theory, that is, a one-nation theory. While true to a large extent, in my understanding the conflict is even more foundational. It is rooted in their respective conceptions of identity after their independence. While India’s identity was a rooted one, that of Pakistan has been in the constant search of one. Let it be underlined that both the words/ phrases, Pakistan and South Asia, are just 70 odd years old, while the notion of India is eternal, it is there from the cradle days of global history. The Greek warrior Alexander came to India as early as in 326 BCE. The beginning of Christianity in India was marked as early as in 52 CE when St. Thomas had arrived in Kerala. India’s western coasts had trade relations with the Arabs even in ancient and medieval times. During the Renaissance, Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama searched for sea routes to India. In colonial India Indology was a huge draw in Western academic circles. India was always the reference point to name new areas. Ergo, we had the Indian Ocean, West Indies, East Indies, and Indo-China. The company that pioneered the British Empire in South and Southeast Asia was called the East India Company. Even the name Indonesia was derived from Indos Nesos, ‘Indian Island’. The Dutch company that traded in Indonesia was called the Dutch East India Company.

This in-built advantage of India cannot be matched by Pakistan however it may try by obliterating all references to its Indian (read Buddhist/Hindu) past as is evident from its history books that gloss over the country’s ancient pre-Muslim India barring the civilizations of Harappa and Mohenjo-Daro, the physical ruins of which earn substantial tourist revenue for the state. There is rampant distortion of history in the country just to show the greatness of Muslims in general and the sub-continental Muslim rulers in particular. SAARC, therefore, presupposes the overshadowing of Pakistan and the identification of the region primarily with that of India, which logically cannot go well with Pakistan’s quest for identity. The resolution of this question is easy to romanticize but difficult to sell politically. Still there is no harm for hoping against hope and to see how SAARC can contribute to regional peace and cooperation, or prepare at least a conducive mood for the same. Here is a brief history to put the subject in perspective.

The Genesis

The idea of South Asian regional cooperation was first mooted in the 1970s. During 1977-80, President Ziaur Rahman of Bangladesh suggested that let the seven states of South Asia (Afghanistan was politically unstable and in 1979 it fell under Soviet occupation) work out a cooperative arrangement to ameliorate the stark economic problems of the region. Although the proposal did not evoke much enthusiasm to start with, it caught the imagination of the regional elites once there were changes in the regional leaderships. It was the time when the political leadership of South Asia was changing hands into a new generation. In India Indira Gandhi’s Congress Party had been replaced by the Janata Party led by Morarji Desai, in Pakistan Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto was replaced by Zia-ul Haq, and in Sri Lanka Sirimavo Bandaranaike was replaced by Junius Jayewardene. In Bangladesh Ziaur Rahman had consolidated his position and there was no immediate threat to him from the pro-Mujib secularist forces. All these leaders had a pro-US image and, unlike their predecessors, tended to build regional relations upon new premises. In India there were talks of a ‘genuine non-alignment’ meaning de-staining its pro-Soviet image.

Ironically, however, the first effective step towards building SAARC was taken at a time when the political landscape of South Asia had almost returned to its earlier state. Indira Gandhi had staged a dramatic come-back in India, which coincided with the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan and the return of the US-Pakistan ‘special relationship’. Indira Gandhi’s virtual endorsement of the Soviet forward move in Afghanistan sharpened the strategic cleavage between India and Pakistan. Still, while all this was happening, in May 1980, Ziaur Rahman sent formal letters to the six South Asian leaders urging serious thought on their behalf for the creation of SAARC. The appeal received lukewarm endorsement. Without directly referring to the political questions and without touching upon sensitive regional issues, the leaders thought it worthwhile to explore areas of mutual economic cooperation just to begin with. It was the time when North-South dialogue had practically run its course and the global recession was increasingly crippling the world economy. Hardest hit was the oil-importing developing world to which South Asia belonged. By the mid-1970s the real growth rates had touched a low of almost two per cent. The ‘second oil shock’ of 1979-80 worsened the situation. In 1980, the balance of trade record of all South Asian countries was pathetic. Against this background, South-South Cooperation in general, and regional cooperation in particular, occupied high priority on the South’s developmental agenda. The creation of SAARC was seemingly a matter of time.

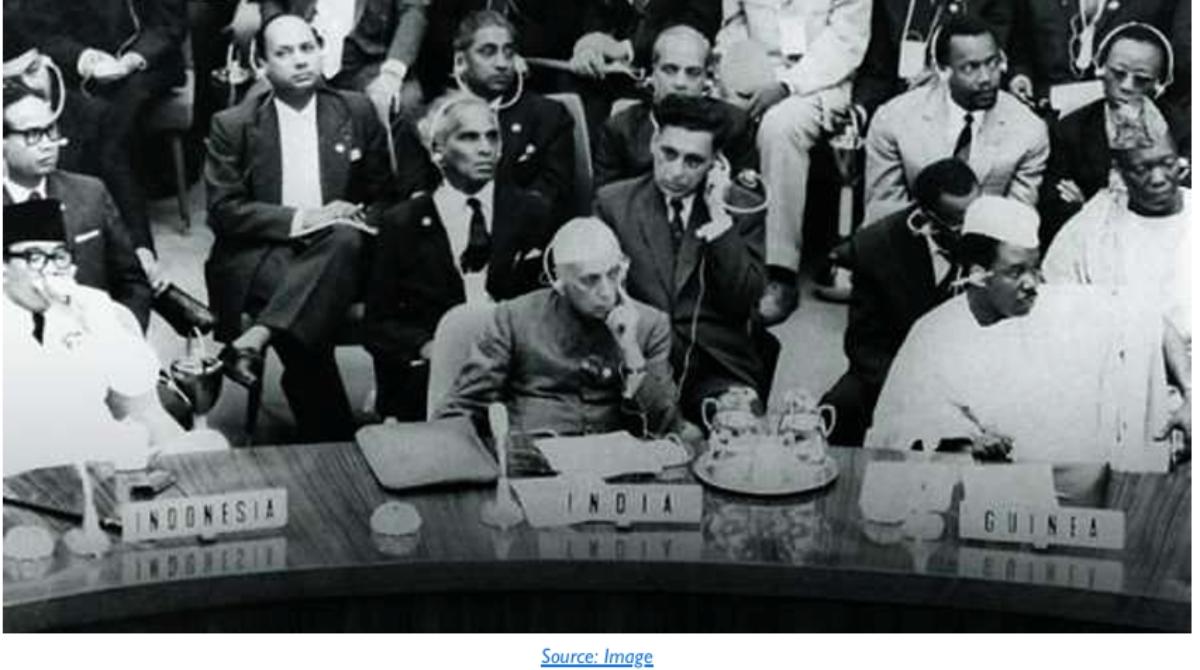

Several meetings soon took place at the secretarial level to identify areas of cooperation. The highlight of these meetings was the evolution of a consensus that no ‘bilateral or contentious’ issues would be discussed. Interestingly, the first point was on India’s insistence and the second, on both India’s and Pakistan’s, the other countries having no particular reason to worry about them. On the contrary, they would have preferred the inclusion of bilateral issues which could have given them confidence to deal with India, the colossus, which was contemptuously characterized as the ‘Big Brother’. In a way, therefore, it was a diplomatic gain for India. In August 1983, the ongoing process was given a political push. At the First Foreign Ministers’ Conference in New Delhi, the South Asian Regional Cooperation (SARC) Declaration was adopted. Following this the organizational structure of SAARC was finalized.

The Organization

In December 1985 at the first Summit Meeting in Dhaka SAARC was formally launched. The assembled leaders decided in favour of a Council of Ministers and a Secretariat, certifying their enduring commitment to the organization. In February 1987, the SAARC Secretariat came into being with a secretary general and four directors. Later, the SAARC Council of Ministers was formed consisting of the foreign ministers of respective member states. The organizational structure of SAARC was a four-tier arrangement. At the lowest level were the Technical Committees of experts and officials formulating programmes of action and organizing seminars and workshops. Next was the Standing Committee of Foreign Secretaries to review and coordinate the recommendations of the Technical Committees, which was to meet at least once a year. Above this was the Foreign Ministers’ Conference, also to be held at least once every year to grant political approval to the recommendations of the Standing Committees. At the apex was the Summit Meeting to be held annually (more frequently if required) to give political significance to the programmes. In 2007 Afghanistan was added to the group a process which was in the making since 2005.

The Record

So far, eighteen Summits have taken place, namely, Dhaka (1985), Bangalore (1986), Kathmandu (1987), Islamabad (1988), Male (1990), Colombo (1991), Dhaka (1993), New Delhi (1995), Male (1997), Colombo (1998), Kathmandu (2002), Islamabad (2004), Dhaka (2005), New Delhi (2007), Colombo (2008), Thimphu (2010), Male (2011), and Kathmandu (2014). About the 19th Summit there is a technical confusion that we have discussed in the beginning of this essay. Notwithstanding this uneven summitry record SAARC has a fairly impressive list of meetings, seminars, studies and reports that it has sponsored. The Calendar of Activities released by the SAARC Secretarial from time to time enumerates a large number of activities pertaining to such diverse developmental fields as agriculture, animal husbandry, horticulture, health and sanitation, forestry, population, meteorology, postal services, drug trafficking and abuse, integrated rural development, transfer of technology, sports, transport, telecommunication, women’s development, trade and commerce, and others.

SAARC’s activities are not confined to developmental issues only. Even such an issue as terrorism, which has been hanging fire in Indo-Pak relations for several years and has serious political overtones, has constantly received attention. Despite deep-rooted divisions among the SAARC countries over this question, they have adopted a convention against terrorism. Its highlight was the identification of offences, which ‘shall be regarded as terrorist and for the purpose of extradition shall not be regarded as a political offence or as an offence inspired by political motives.’ The convention provides the necessary follow-up through the signing of bilateral extradition treaties, which however have not yet been signed. In the 15th SAARC Summit held in Colombo (2008) the SAARC Convention on Mutual Legal Assistance in Criminal Matters was one of the most significant and tangible step. The Convention, which was signed by the Foreign Ministers of the eight SAARC states sought to provide the legal basis that aimed to harmonize different domestic legal systems of countries which would facilitate mutual legal assistance in criminal matters, namely investigations, prosecution and resultant proceedings. The Convention thus obviated the need to negotiate separate bilateral agreements with individual countries in the region, which has not been carried forward though.

SAARC’s biggest success is in the field of energy cooperation and connectivity but the problem here is that they are all being operationalized at the sub-regional level involving Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal (BBIN connectivity project, for example) thereby re-conceptualizing SAARC sans Pakistan. The choice is one’s own, whether to treat it as the organization’s success, or its ultimate failure. Obviously the latter, objectively speaking. Also, one of the major thrusts of SAARC when it was launched was to promote free trade in the region. But after all these years of hectic brainstorming by the region’s economists and other stake holders the result is virtually nil. Intra-regional trade still accounts for merely 5 per cent of the region’s global trade. The hard reality is that even in the best of times, South Asian economies are competitive, not complementary. The economic integration of the region remains a pipe dream.

SAARC and COVID-19

There was a flicker of hope recently to revive the paralysed SAARC when on 14 March 2020, against the background of the scourge of the COVID pandemic, India took the initiative to call a web-based SAARC ‘Summit’ to address the problem. Though India and Pakistan continued to play ball on their expected lines still at least they all agreed to contribute to a common emergency fund. The respective contributions to the fund in US dollars were as follows: India,10 million; Sri Lanka, 5 million; Pakistan, 3 million; Bangladesh,1.5 million; Afghanistan and Nepal,1 million each; Maldives, 200,000; and Bhutan, 100,000: total US$ 21.8 million. Two negative points, however, haunt. One, there is still no agreement over following one single procedure in terms of disbursing the funds, and two, compared to, for example, the European Union, the SAARC fund is too small to be meaningful. A similar EU fund goes into hundreds of billions of dollars and administratively it is far better organized.

Some Concluding Thoughts

One does not need to be either a diplomat or a politician to expect a few basic things from the SAARC. Agreed that to ask it to discuss bilateral or contentious issues would still be a tall order. But one can start with a couple of innocent confidence building moves. At academic and Track II levels the region has had enough discussions on CBMs (confidence building measures) which mostly have concentrated on avoiding accidental nuclear wars or escalating border skirmishes. Let the agenda be taken to the people’s level now. South Asia is a civilizational space where all kinds of sects and ideologies have coexisted, not always peacefully, but not that unmanageably either. One is not asking for the reordering of the present state system which would amount to asking for the moon.

All that one is asking is to take two small steps, one, more tourist flows, particularly between India and Pakistan, and two, more intra-regional academic exchanges. The region’s obsession with security has made the region one of the most insecure in the world.

It is high time that SAARC is rescued from its impending collapse. Let the Indian leadership be statesmanlike by making the situation conducive for Pakistan to summon the stalled 19th Summit without insisting upon it to officially renounce terrorism (such promises were made in the past as well). Let India accept the reality that it is not impossible to deal with a terrorism-promoting Pakistan. India has done so in the past. Pakistan’s presence in the SAARC will not make it renounce terrorism as its policy tool but it would, at least potentially, temper its adventurism. A regular SAARC Summit together with a relaxed visa regime that boosts tourism and academic exchanges would go a long way to melt the cloud, hopefully. Let this new regime be tried for just five years. Heaven will not fall if it does not work. Let us concede that most big things start with small dreams.