Abstract

With Palestine as the contextual framework, this article deconstructs the working of realpolitik and the impact it has on humanity. While individual cases differ, following strands stand out:

- The fear of military power dictates political and economic alliances

- double speak and obfuscation become instruments to justify unjust actions

- the argument of “national interest” is stretched to unleash devastation and death on gargantuan scale that is as mindless as ineffective

Deconstructing Realpolitik – from Concept to Reality

The driving force behind realpolitik is power. Realpolitik suggests a no-nonsense view and a disregard for ethical, i.e. involving or expressing moral approval or disapproval, considerations. In diplomacy it is often associated with relentless, though realistic, pursuit of the national interest. The concept was an early attempt at answering the conundrum of how to achieve liberal enlightened goals in a world that does not follow liberal enlightened rules.

Over time, realpolitik has come to represent two things for furtherance of national interest: pursuing economic well-being without any let or hindrance, and security. While there’s much merit in both these instruments of national interest, the security aspect often takes on macabre forms with horrendous consequences.

Without ignoring the efficacy of realpolitik in the pursuit of national interest, this paper tries to focus on the terrible consequences of the exercise of power. This paper takes a close look at this second aspect through the prism of Palestine.

Realpolitik – How world leaders behave

Pratap Bhanu Mehta expounds the same view in his piece, “What Israel-Palestine conflict reveals about world leaders”[1]. He holds that Israel-Hamas conflict shows governments today are making bedfellows of extremists. States across the world are pushing societies deeper into the abyss and amidst this carnage and heightened political risk of a wider conflict; there is not one significant world leader who is acting in a way that is not morally myopic or politically ill-judged. Mehta elaborates:

Iran always has maintained an infrastructure of violence that has served its political purposes but destroys the societies in which they are embedded, from Palestine to Lebanon. The Arab regimes have nurtured the Palestinian cause as a pretext, but have little concern for their welfare. The gap between Europe’s perception of its own importance and its power has never been greater; Macron’s civilising mission is now reduced to simply curbing free discussion on the Palestine issue and Germany’s idea of moral nuance is to de-platform Palestinian writers.

Even Turkey is more interested in using Palestine for its neo-Ottoman fantasies. As for the rest of the world, it was important that the UN General Assembly at least make a humanitarian gesture asking for a ceasefire. But it is a toothless advisory and not a single country has an action plan to stop the unfolding carnage in Gaza. Mehta also feels it was a misjudgement not to pass a resolution condemning Hamas. This is not because a ceasefire in Gaza should be linked to condemning Hamas, or for the sake of neutrality or two-sidedness.

But condemning Hamas is the morally right and the politically prudent thing to do. China can at best watch from the sidelines; at worst smell an opportunity in the self-destruction of the West. Mehta has also an interesting take on India: “As for India, one anecdote will suffice. I was at an international meeting recently, where someone, not unsympathetic to India, asked this question: “India claims to be the leader of the Global South. But let us ask the question, ‘who is following it?’”

Realpolitik of America as the root cause of Israel-Palestine war

Just recently Henry Kissinger – the greatest exponent of realpolitik passed away at the grand old age of 100. What is remarkable is that major newspapers have recounted the devastation and human tragedy caused by Kissinger’s realpolitik:

“Kissinger’s legacy extends beyond the corpses, trauma, and suffering of the victims he left behind. His policies, Grandin told The Intercept, set the stage for the civilian carnage of the U.S. war on terror from Afghanistan to Iraq, Syria to Somalia, and beyond. “You can trace a line from the bombing of Cambodia to the present,” said Grandin, author of “Kissinger’s Shadow”. “The covert justifications for illegally bombing Cambodia became the framework for the justifications of drone strikes and forever war. It’s a perfect expression of American militarism’s unbroken circle.”[2]

Kissinger and the Presidents he served have already demonstrated that leader behaviour is crucial to the play of realpolitik and the devastation that this causes to society. At most one may contend that his brilliance was that of the devil and being America’s most powerful diplomat, his sway on executing foreign policy is unlikely to be replicated. However, this argument doesn’t hold water.

Recently, John Mearsheimer, an international relations scholar at University of Chicago and one of the most influential and controversial thinkers in the world on the topics of war and power, in a podcast on Israel-Palestine, Russia-Ukraine, China, NATO and WW3[3] lays bare the ruthlessness behind the actions of the powerful that has caused and is causing untold devastation in Gaza.

Writing for a recent issue of Foreign Policy (Oct 18, 2023)[4], Stephen M. Walt, the Robert and Renée Belfer professor of international relations at Harvard University, tries to locate the causes of the present bloody conflict between Zionist Israelis and Palestinian Arabs:

“Inevitably, arguing over which of the immediate protagonists is most at fault obscures other important causes that are only loosely related to the long conflict between Zionist Israelis and Palestinian Arabs. We should not lose sight of these other factors even during the present crisis, however, because their effects may continue to echo long after the current fighting stops.

Where one begins to trace causes is inherently arbitrary – Theodor Herzl’s 1896 book, The Jewish State? the 1917 Balfour Declaration? the Arab revolt of 1936? the 1947 U.N. partition plan? the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, or the 1967 Six-Day War? But I’ll start in 1991, when the United States emerged as the unchallenged external power in Middle East affairs and began trying to construct a regional order that served its interests.”

Walt goes on to state that the 1991 Gulf War and its aftermath, the Madrid peace conference, the United States was firmly in the driver’s seat. Yet Madrid also contained a fateful flaw, one that sowed the seeds of much future trouble. Iran was not invited to participate in the conference, and it responded to being excluded by organizing a meeting of “rejectionist” forces and reaching out to Palestinian groups—including Hamas and Islamic Jihad—that it had previously ignored.

Iran viewed itself as a major regional power and expected a seat at the Madrid table, which was “not seen as just a conference on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, but as the defining moment in forming the new Middle East order.” Tehran’s response to Madrid was primarily strategic rather than ideological: It sought to demonstrate to the United States and others that it could derail their efforts to create a new regional order if its interests were not taken into account.

And that is precisely what happened, as suicide bombings and other acts of extremist violence disrupted the Oslo Accords negotiation process and undermined Israeli support for a negotiated settlement. Over time, as peace remained elusive and relations between Iran and the West deteriorated further, the ties between Hamas and Iran grew stronger.

Palestine-Israel war, the violence of pure identity

Delving into the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Sa’di and Abu-Lughod’s study’s outlines the historical emergence of Palestinian collective memory, the challenges to it by marginalized voices and the moral and political implications of its erasure by citing,

“Palestinians preserved their historical heritage and integrated it into their contemporary lives using various symbols, maps, land deeds, house keys, stories, customs, and poetry. By employing diverse theories and approaches, researchers have shed light on how the Palestinian displacement from their homeland continues to impact their cultural identity in the present.”[5]

Sanjay Srivastava, Professor, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, SOAS, University of London calls the Palestine-Israel war, the violence of pure identity. According to him, the recurring tragedy that is the Palestine-Israel relationship tell us about the dangers of interpreting human histories through the constraining lens of religious imagination, and Palestine’s tragedy — and the extraordinary human suffering it has caused — is a cautionary tale for all societies that seek to flatten complex histories of co-existence among populations into the fiction of the “superiority” of any one group over others.

The history of the “ethnic cleansing” of Palestinians remains largely an untold story- not merely as the political event of the establishment of the state of Israel (or loss of Palestine), nor even as the humanitarian event of the creation of the world’s most enduring military occupation and refugee problem, but rather as the existential experience that continues to define most Palestinian history, shatters their society and at the same time consolidates their shared national consciousness.

This narrative is notably eclipsed by pervasive public commemorations of the Holocaust and celebrations of Israel’s establishment, much of which, as Norman G. Finkelstein succinctly puts it, is “a tribute not to Jewish suffering but to Jewish aggrandizement” (2001: 8). The near-total omission of Palestinians’ history of al-nakba[6] from mainstream academic and public discourses in Europe and the US has nevertheless not impeded the continued cultural life of memorizations of the catastrophe across different generations of exiled Palestinians.

This exposes the intentional strategies of Zionist leaders. Indeed, memories of al-nakba reinforce the centrality of the land in Palestinian discourses of identity. “Throughout history, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, amidst adversity, have showcased remarkable resilience in preserving their cultural identity and unity. Despite facing numerous challenges, these communities have managed to maintain their heritage and cohesion, serving as a testament to their strength and determination.”[7]

But more tellingly, multiple Jewish and Israeli scholars of the Holocaust – like Omer Bartov and Raz Segal have raised the issue of genocide. Segal, an associate professor of Holocaust and Genocide Studies at Stockton University in New Jersey, has accused Israel of a “quite explicit, open and unashamed” genocidal assault on Gaza. Writing in Jewish Currents days after Israel launched its military retaliation against the Hamas attack, Segal said the country was already committing three of the five acts stipulated in the UN genocide convention. He defined these as:

“1. Killing members of the group. 2. Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group. 3. Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”

History of Conflict and Displacement in Palestine/Israel

Having looked at the scale of human tragedy, we now proceed in this section to the larger question of displacement. In this larger tragedy, realpolitik has not only provided no answer, but has complicated the situation where there seems no escape. Power, the bedfellow of realpolitik, has rewarded the more powerful and dispossessed the weak. And war is the medium through which this power is first wielded; later, the negotiating power of the victor and its allies have legitimised the displacement.

First, a little bit of context. An article in The Indian Express, “How Jews first migrated to Palestine, and how Israel was born”, stated that much before the official creation of Israel in May 1948, Jewish migrants had been settling in Palestine. And rhetorically, two questions are posed: “How did Palestine ‘end up paying for Europe’s crimes’? And “How did the Jews manage to carve out a state in a land where they were a small minority?”[8]

The Jewish migration (Aliyah) to Palestine began sometime before World War I. The first wave of arrivals, from 1881 to 1903, is known as the First Aliyah. The migrants began to buy large tracts of land and set to farming it. Very soon, these arrivals meant losses for the native Palestinians, but it was some years yet before the conflict would be framed in these terms.

What possibly changed the face of West Asia forever was the Balfour Declaration of 1917 (named after then British Foreign Secretary Arthur James Balfour) to a wealthy British Jew, Baron Lionel Walter Rothschild. This sealed the fate of lakhs of Palestinians. The British government needed Jewish support in its World War I efforts. To secure that, Balfour backed the Zionist cause. His letter to Rothschild read:

“His Majesty’s Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”[9]

The Express article holds that this would become the template for many future resolutions on Palestine — while there would always be some lines about the “rights of Palestinians”, little would be done on the ground about it.

After World War I, the Arab frustration and feelings of being cheated were erupting into attacks on Jewish settlements, on railroad tracks, on civilians. There were some attempts at talks between Jews and Arabs; notable being a 1919 pact, that soon came to nothing. The years 1936 to 1938 saw immense bloodshed, with Palestinians attacking Jews and the British, the British imposing collective punishment on Palestinian villages, and the Jews carrying out killings of their own. The Palestinians call this period ‘al-thawra al-kubra’, or the great rebellion. One of the armed groups was called Black Hand, led by Izzedin al-Qassam. The military wing of Hamas today is called the al-Qassam Brigades.

Around this time, the Peel Commission, set up by the British, proposed partition as the only solution to the problem. The Jewish side negotiated for better terms, but the Palestinian side boycotted the suggestion. In May 1939, a White Paper released by the British was much more favourable to the Palestinian side. However, the divided Palestinian leadership did not capitalise on the chance. Eventually, the British did what they had with Partition violence in India — let trouble simmer to breaking point and then withdraw.

In 1947, with neither side agreeing to a partition or any other solution, and distrust and hostility at an all-time high, the British announced they were exiting Palestine, and the question would be settled by the UN. On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted to divide Palestine into Jewish and Arab states, with Jerusalem under UN control. The proposed Jewish state was to consist of 55 per cent of the country, including the largely unpopulated Negev desert. Its population would comprise some 500,000 Jews and 400,000 Arabs. The Arab state was to have 44 per cent of the land and a minority of 10,000 Jews.” The Arab areas would include the West Bank and Gaza.[10]

The outraged Palestinian side rejected the resolution. Israel, on the other hand, declared independence on May 14, 1948. This entire period was marked by civil war, and the Israeli military groups managed to drive out a large number of Palestinians. The creation of Israel is called Naqba, or the catastrophe, by Palestinians, who see it as the day they lost their homeland.

Immediately after Israel’s declaration of independence, it was invaded by Egypt, Jordan, Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon. However, the determined Israeli side, bolstered by arms and funds from the US, managed to beat them back. The 1949 Armistice Agreements between Israel and neighboring Egypt, Lebanon, Jordan, and Syria ended the hostilities of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. In the peace deal Israel and Arab states divided up the land. No Palestinian state was created; Egypt controlled Gaza while Transjordan (later Jordan) formally annexed the West Bank.

After fighting stopped in the 1948 war, Israel refused to allow refugees to return to their homes. Since then, Israel has rejected Palestinian demands for a return of refugees as part of a peace deal, arguing that it would threaten the country’s Jewish majority. Displacement has been a major theme of Palestinian history. In the 1948 war around Israel’s creation, an estimated 700,000 Palestinians were expelled or fled from what is now Israel. Palestinians refer to the event as the Nakba, Arabic for “catastrophe.”

Wars and the realpolitik of accommodation

In the 1967 Mideast war, when Israel seized the West Bank and Gaza Strip, 300,000 more Palestinians fled, mostly into Jordan. The refugees and their descendants now number nearly 6 million, most living in camps and communities in the West Bank, Gaza, Lebanon, Syria and Jordan. The diaspora has spread further, with many refugees building lives in Gulf Arab countries or the West.

The Yom Kippur war erupted in October 1973, on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, Egypt and Syria launched an attack in Sinai and the Golan Heights. The war lasted three weeks and ended with a ceasefire secured by the UN. But it wasn’t until 1978 that the Camp David accords were signed by Israel and Egypt. In a peace treaty six months later Israel agreed to give back Sinai to Egypt, and to grant Palestinians autonomy.[11]

The next major development was in 1993 when Israel and the Palestinians, represented by the Palestine Liberation Organisation, signed the first Oslo accord, which set out a five-year period of Palestinian autonomy in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip under a new entity, the Palestinian Authority. The Oslo II accords, under which Israel handed over security responsibility to the Palestinian Authority in parts of the occupied territories, were signed in 1995 with the intention of a permanent treaty five years later. That did not happen.[12]

Five years later came the Abraham accords with bilateral agreements on Arab-Israeli normalisation signed in 2020. The name of the Abraham Accords is rooted in the common belief of the Abrahamic religions – particularly Judaism, Christianity and Islam – regarding the role of Abraham as a spiritual patriarch. The first round of deals was between Israel and the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain in September 2020. Sudan normalised relations with Israel the following month and Morocco in December 2020. Negotiations between Israel and Saudi Arabia were disrupted by the war between Israel and Hamas which began in October 2023.

The Abraham accords are a perfect example of the “practical” aspects of realpolitik – focus on economic benefits without being encumbered by ideological or moral constraints; more so under the stewardship of the master deal maker, former US President Donald Trump.

In exchange for Morocco’s recognition of Israeli sovereignty, the United States recognized Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara. For the Sudan-Israel normalisation which is still on-going, the United States has incentivized the deal by agreeing to drop Sudan’s status as a “State Sponsor of Terrorism” while also providing a loan of US$1.2 billion to help the Sudanese government clear the country’s debts to the World Bank. Although Sudan signed the declarative section of the agreement, it did not sign the corresponding document with Israel, unlike the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain.[13]

So, in spite of all the talk about Arab support for Palestinian cause, none of the above treaties and accords address the issue of mass displacement of Palestine people. It was as if, over time, the Palestine issue was not just put on the backburner but a non-issue. The deadly and horrific terrorist attack by Hamas on Israel in October 2023 which killed around 1200 civilians and the capture of 240 hostages and the even more brutal retaliation by Israel Defence Force has brought back the Palestine issue centre stage all over the world.

On November 2, 2023, in view of the ongoing Israel-Hamas war, Bahrain said in a statement that the Israeli ambassador left Bahrain, that Bahrain recalled its ambassador to Israel, and suspended all economic relations with Israel, citing a “solid and historical stance that supports the Palestinian cause and the legitimate rights of the Palestinian people.” The statement was made by Bahrain’s parliament and Israel said they had no knowledge of the decision.[14]

Gaza: Scarred, ruined, and silenced by death

This is the evocative title of Salam Abu Sharar’s piece recently published in Frontline[15] where he says that with Israel dropping 6,500 bombs in a week, the number the US used in Afghanistan in a year, the people of Gaza focus only on recognising the dead. Andre Damon says that after two weeks of constant bombardment that killed dozens of doctors, patients and refugees, Israeli forces entered Al-Shifa hospital and raised the Israeli flag over it and thus “Israel’s war on hospitals has normalized war crimes”[16].

But does anything happen on its own? Do we see the working of another crusader of realpolitik; another Kissinger? Writing for The Guardian, columnist Robert Tait quotes Jewish holocaust scholar, Omer Bartov, a professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Brown University in Rhode Island, that multiple Israeli ministers and senior figures, including the prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, had made “genocidal statements” and “terrifying pronouncements” that have never been revoked. Bartov also singled out comments by Maj Gen Giora Eiland, a former head of the Israeli national security council who told Israel’s Yedioth Ahronoth newspaper on 10 October that

“Gaza will become a place where no human being can exist. “The way to win this war faster and at a lower cost to us necessitates the collapse of the systems on the other side, not the killing of more Hamas fighters,” wrote Eiland, who expanded his enemy definition to include the Gaza population whom he said cheered Hamas’s atrocities… The international community warns us of a humanitarian disaster in Gaza and of severe epidemics. We must not be deterred by that … severe epidemics in the southern strip will bring victory closer and diminish the number of IDF [Israeli Defense Forces] casualties.”

Robert Tate further notes Bartov’s conclusion: “Israeli rhetoric and actions are preparing the ground for what may well become mass killing, ethnic cleansing and genocide, followed by annexation and settlement of the territory.”.[17]

No guarantee of return

That’s in part because there’s no clear scenario for how this war will end. Israel says it intends to destroy Hamas for its bloody rampage in its southern towns. But it has given no indication of what might happen afterward and who would govern Gaza. That has raised concerns that it will reoccupy the territory for a period, fueling further conflict.

The Israeli military said Palestinians who followed its order to flee northern Gaza to the strip’s southern half would be allowed back to their homes after the war ends. Egypt is not reassured. El-Sissi said fighting could last for years if Israel argues it hasn’t sufficiently crushed militants. He proposed that Israel house Palestinians in its Negev Desert, which neighbors the Gaza Strip, until it ends its military operations. Riccardo Fabiani, Crisis Group International’s North Africa Project Director says, “Israel’s lack of clarity regarding its intentions in Gaza and the evacuation of the population is in itself problematic (and) [T]his confusion fuels fears in the neighborhood.”[18]

Egypt has its own problems. It is dealing with a spiraling economic crisis and already hosts some 9 million refugees and migrants, including roughly 300,000 Sudanese who arrived this year after fleeing their country’s war. But Arab countries and many Palestinians also suspect Israel might use this opportunity to force permanent demographic changes to wreck Palestinian demands for statehood in Gaza, the West Bank and east Jerusalem, which was also captured by Israel in 1967.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi made his toughest remarks, saying the current war was not just aimed at fighting Hamas, which rules the Gaza Strip, “but also an attempt to push the civilian inhabitants to migrate to Egypt.” He warned this could wreck peace in the region.

Jordan’s King Abdullah II gave a similar message a day earlier, saying, “No refugees in Jordan, no refugees in Egypt.” Their refusal is rooted in fear that Israel wants to force a permanent expulsion of Palestinians into their countries and nullify Palestinian demands for statehood. Egypt fears history will repeat itself and a large Palestinian refugee population from Gaza will end up staying for good.[19]

Palestine-Israel Conflict, the violence of pure identity

Delving into the heart of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, Sa’di and Abu-Lughod’s study’s outlines the historical emergence of Palestinian collective memory, the challenges to it by marginalized voices and the moral and political implications of its erasure by citing, “Palestinians preserved their historical heritage and integrated it into their contemporary lives using various symbols, maps, land deeds, house keys, stories, customs, and poetry. By employing diverse theories and approaches, researchers have shed light on how the Palestinian displacement from their homeland continues to impact their cultural identity in the present.”[20]

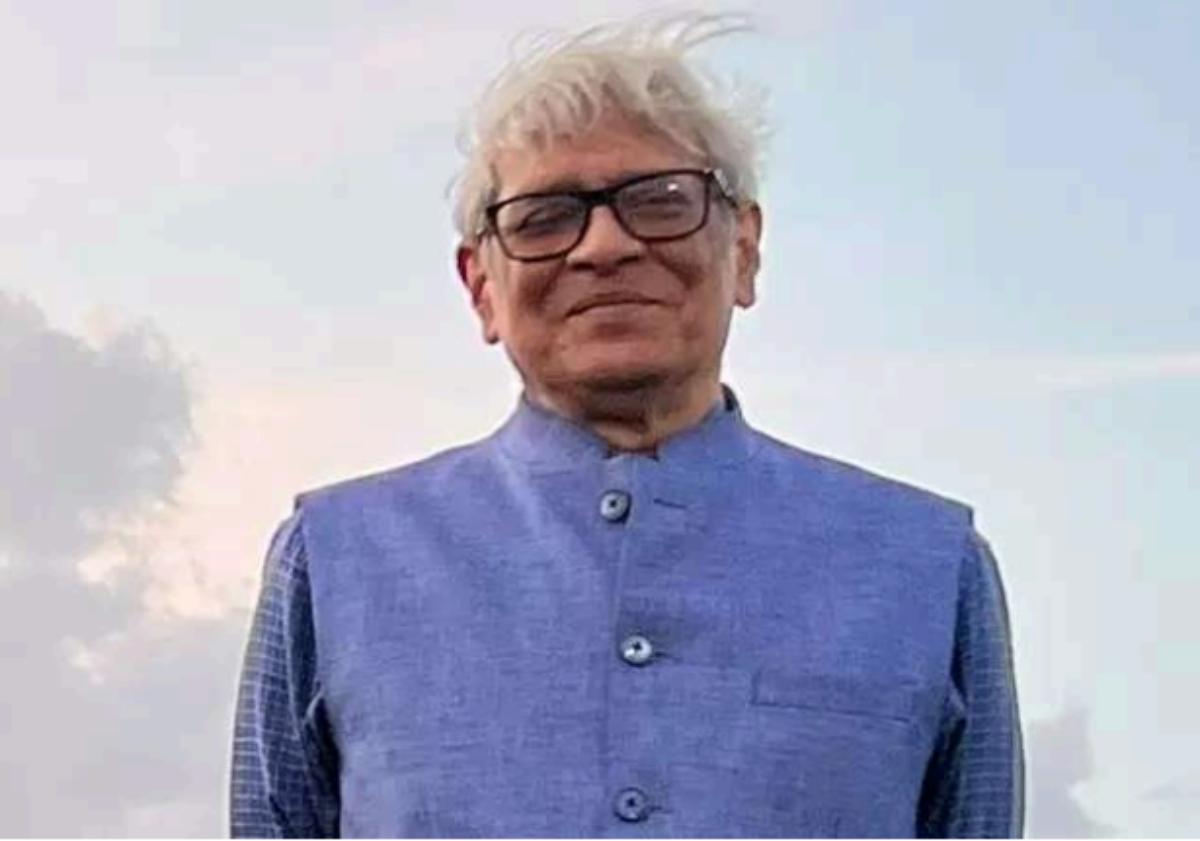

Sanjay Srivastava, British Academy Global Professor, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, SOAS University of London calls the Palestine-Israel war, the violence of pure identity. According to him, the recurring tragedy that is the Palestine-Israel relationship tell us about the dangers of interpreting human histories through the constraining lens of religious imagination, and Palestine’s tragedy — and the extraordinary human suffering it has caused — is a cautionary tale for all societies that seek to flatten complex histories of co-existence among populations into the fiction of the “superiority” of any one group over others.

The history of the “ethnic cleansing” of Palestinians remains largely an untold story- not merely as the political event of the establishment of the state of Israel (or loss of Palestine), nor even as the humanitarian event of the creation of the world’s most enduring military occupation and refugee problem, but rather as the existential experience that continues to define most Palestinian history, shatters their society and at the same time consolidates their shared national consciousness.

This narrative is notably eclipsed by pervasive public commemorations of the Holocaust and celebrations of Israel’s establishment, much of which, as Norman G. Finkelstein succinctly puts it, is “a tribute not to Jewish suffering but to Jewish aggrandizement” (2001: 8). The near-total omission of Palestinians’ history of al-nakba from mainstream academic and public discourses in Europe and the US has nevertheless not impeded the continued cultural life of memorizations of the catastrophe across different generations of exiled Palestinians.

This exposes the intentional strategies of Zionist leaders. Indeed, memories of al-nakba reinforce the centrality of the land in Palestinian discourses of identity. “Throughout history, Palestinian refugees in Lebanon, amidst adversity, have showcased remarkable resilience in preserving their cultural identity and unity. Despite facing numerous challenges, these communities have managed to maintain their heritage and cohesion, serving as a testament to their strength and determination.”[21]

But more tellingly, multiple Jewish and Israeli scholars of the Holocaust – like Omer Bartov and Raz Segal have raised the issue of genocide. Segal, an associate professor of Holocaust and genocide studies at Stockton University in New Jersey, has accused Israel of a “quite explicit, open and unashamed” genocidal assault on Gaza. Writing in Jewish Currents days after Israel launched its military retaliation against the Hamas attack, Segal said the country was already committing three of the five acts stipulated in the UN genocide convention.

He defined these as: “1. Killing members of the group. 2. Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group. 3. Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.”

India and Palestine – the journey from idealism to realpolitik

India emerged as a significant player in international diplomacy on this issue. The roots of this thinking can be attributed to Mahatma Gandhi.

In an article published in Harijan on November 26, 1938, Mohandas Karmachand Gandhi began by admitting that it was “a very difficult question” and that he was sympathetic to their “age-long persecution” of the Jews. But he proceeded to see it in the light of the valid claims of the other side. “My sympathy does not blind me to the requirements of justice,” he wrote. “The cry for the national home for the Jews does not make much appeal to me…Why should they not, like other peoples of the earth, make that country their home where they are born and where they earn their livelihood?…Palestine belongs to the Arab in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French.”[22]

He also exhorted both the Jews and the Arabs to follow a non-violent approach to conflict resolution. He made it a point to say that he was not “defending the Arab excesses” in resisting what they rightly regarded as an “unwarrantable encroachment upon their country”. But he also noted the heavy odds faced by Palestine in such resistance as he condemned the violent nature of the fight for the homeland of the Jews “under the shadow of the British gun”. Deploring the use of “the bayonet or the bomb” in the struggle, he urged Jews to seek settlement in Palestine only by the goodwill of the Arabs, and by attempting a change of Arab heart.

From heady support to measured equidistance

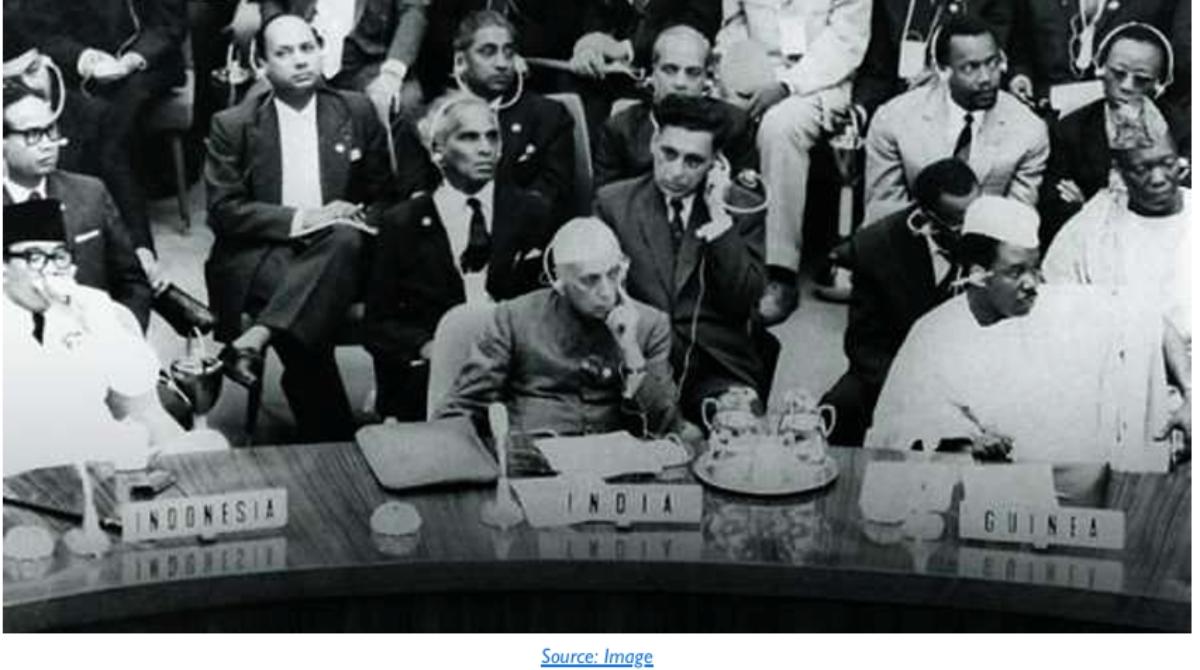

Thus, India’s solidarity with the Palestinian cause has historically been beyond rhetoric. In 1947, India voted against the partition of Palestine at the United Nations General Assembly. India was the first Non‐Arab State to recognize PLO as sole and legitimate representative of the Palestinian people in 1974. India was one of the first countries to recognize the State of Palestine in 1988. All this is because the sentiment of solidarity with the Palestinian cause in India has deep socio-historic and geo-economically strategic roots, and it has frequently played a significant role in shaping India’s foreign policy concerning the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[23]

The Congress Party’s legacy of support for the Palestinian cause dates back to India’s independence movement where leaders like Jawaharlal Nehru who served as India’s first Prime Minister, were staunch advocates for Palestinian self-determination. Palestinian students often came to Indian colleges at that time right up to the 1980s and in 1978 the government even allowed the PLO to open an office in Delhi. [24] In 1996, India opened its Representative Office in Gaza, which was later shifted to Ramallah (in the West Bank) in 2003. Even prominent leader, Yassar Arafat was seen weeping at the funeral of “his sister, Indira Gandhi.”[25]

India’s position was that it supported “the Palestinian cause and called for a negotiated solution resulting in a sovereign, independent, viable and united State of Palestine, with East Jerusalem as its capital, living within secure and recognised borders, side by side at peace with Israel”. Then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh stated this position in November 2013. So did then President Pranab Mukherjee, in October 2015. Stanly Johny, International Affairs Editor at The Hindu writes that until 2017.

India dropped the references to East Jerusalem and the borders in 2017 when Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas visited Delhi. Prime Minister Narendra Modi said back then, “[W]e hope to see the realisation of a sovereign, independent, united and viable Palestine, coexisting peacefully with Israel. I have reaffirmed our position on this to President Abbas during our conversation today.” In 2018, when Mr. Modi visited Ramallah, he reaffirmed the same position, with no direct reference to the borders or Jerusalem.[26]

Asked about this subtle change in India’s position, a senior diplomat with the MEA told The Hindu in 2018 during PM Modi’s Palestine visit that the issues of border and capital are among the most contentious of the Israel-Palestine conflict. “So it’s up to the parties to reach a consensus on these issues. As regards we are concerned, we support the two-state solution, which means we support statehood for the Palestinians.” It is this position India has reiterated during the latest Gaza crisis.

India and Israel: has realpolitik nudged out the Palestinian cause?

As we have observed earlier, realpolitik has essentially two dimensions, economic and security. In the case of Indo-Israeli relations, both these elements come into play. Though it was only after the Oslo peace process was underway in 1992 did India open formal diplomatic ties with Israel. Over the subsequent decade, a burgeoning if still understated defense and technology partnership brought Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon to New Delhi in 2003. By then, Israel was already India’s second largest arms supplier after Russia. Yet, as a recent United States Institute of Peace (USIP) analysis puts it

“…Modi ushered India’s relations with Israel completely out of the shadows. In 2017, he took a celebrated and much-photographed trip to Israel, the first for any Indian prime minister. Then in 2018, he feted Netanyahu in New Delhi. The Modi-Bibi “bromance” captured headlines in both nations, as the two took pains to play up their partnership.”[27]

The tilt toward Israel has been aided by at least two geopolitical developments. First, India has deepened its economic and diplomatic ties with UAE (with a lessening of its traditional ties with Iran and Egypt), and UAE itself has moved closer to Israel, culminating in the Abraham accord. The second has been I2U2, the coming together of the foreign ministers of India, Israel, UAE and USA in 2021.

So possibly it wasn’t a surprise that Prime Minister Modi was the first major leader to tweet “India’s solidarity with Israel at this difficult hour” after the October 7 Hamas attack on Israel, and three days later a further tweet “People of India stand firmly with Israel in this difficult hour. India strongly and unequivocally condemns terrorism in all its forms and manifestations.” It was only on October 12 the Indian Ministry of External Affairs reiterated India’s longstanding position in support of a two-state solution for Israel and Palestine, on October 18 in the immediate aftermath of the Al-Ahli hospital blast, Modi pointedly avoided fixing blame on Israel, tweeting only general condolences and concern.

Then, on October 27, New Delhi joined 44 other countries in abstaining from the symbolic United Nations General Assembly resolution for a humanitarian cease-fire in Gaza. If one thought that this was no more than a subtle shift with little significance, Sonia Gandhi’s op-ed in The Hindu removed any doubt:

“The Prime Minister had made no mention of Palestinian rights in the initial statement expressing complete solidarity with Israel.” She added, “The Indian National Congress is strongly opposed to India’s abstention on the recent United Nations General Assembly Resolution.”[28]

But the USIP analysis referred to earlier has an explanation for New Delhi’s evolving stand on Israel-Hamas war:

“Modi’s India now has a major stake in avoiding any regional military escalation that would destroy such prospects for good. Thus, whatever sympathy Indians may have for Palestinian civilians, New Delhi has none for Hamas or its backers in this fight. A quick Israeli victory followed by the imposition of a Gulf-friendly governing authority in Gaza would serve Modi’s purposes better than any other outcome. If instead the flames of Gaza ignite the wider region in war, India would see its past diplomatic investments go up in smoke and, worse, could face the dangerous prospect of a reinvigorated terrorist threat at home as well.”[29]

One can therefore argue that India’s strategic considerations have now essentially been reversed. India had once reluctantly embraced Israel because of its burgeoning defense and national security needs. But its ideological sympathies then lay with the Palestinian cause. Today, India reluctantly expresses solidarity with Palestine because it doesn’t want to alienate partners in the Arab world. But its sympathies now lie with Israel.

Polarisation of India and Its Impact

Sociologists are likely to explain that this shift in sympathies is undergirded by the worldview of a significant section of Indians who perceive their country as an ethno-nationalist majoritarian state facing the existential threat of Islamist terrorism, and who always saw elements of Israel in their own vision of India. Indeed, they were strong proponents of normalization of relations with Israel long before it became India’s policy.

This shift is significant, more so when the state power and social structure tend to conflate. On the ground therefore, there’s no nuanced statements or actions. An article in The Diplomat captioned “A Changed India Looks, Emotes, and Thinks Like Israel” reports:

“In the state of Uttar Pradesh, Chief Minister Yogi Adityanath issued orders to crack down on those supporting Palestine. Uttar Pradesh police suspended a Muslim constable for a fundraising post in support of Palestine. A case was also registered against an unidentified person for posting pictures of aerial bombings of Gaza. Meanwhile, prominent Indian news anchors declared that Israel’s war against Hamas was a “war for all of us.”[30]

This is not to suggest a wholesale shift. India is a vast and heterogeneous country and on the Palestine question. nothing captures this more than the pair of pictures below.

[1] https://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/israel-palestine-conflict-ghaza-israel-war-muslim-countries-stand-on-palestine-9006499/

[2] https://theintercept.com/2023/11/29/henry-kissinger-death/

[3] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4wLXNydzeY

[4] Https://Foreignpolicy.Com/2023/10/18/America-Root-Cause-War-Israel-Gaza-Palestine/

[5]Saloul, I. A. M. (2009). Telling memories: Al-Nakba in Palestinian exilic narratives. [Thesis, Universiteit van Amsterdam], pp. 3-7.

[6] Al-nakba means catastrophe in Arabic. It refers to the mass displacement and dispossession of Palestinians during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. Before the Nakba, Palestine was a multi-ethnic and multi-cultural society . https://www.un.org/unispal/about-the-nakba

[7]Ibid.

[8] https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-history/how-jews-first-migrated-to-palestine-how-israel-was-born-8983611/

[9] Ibid

[10] Ibid

[11] https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2023/11/20/the-a-to-z-of-the-arab-israeli-conflict

[12] Ibid

[13] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Accords

[14] ibid

[15] https://frontline.thehindu.com/world-affairs/death-gaza-strip-in-israel-bombings/article67469653.ece

[16] https://www.wsws.org/en/articles/2023/11/16/tltc-n16.html

[17] https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2023/dec/04/john-kirby-white-house-genocide

[18] ibid

[19] https://indianexpress.com/article/explained/explained-global/egypt-arab-countries-palestine-refugees-gaza-explained-8990382/

[20]Saloul, I. A. M. (2009). Telling memories : Al-Nakba in Palestinian exilic narratives. [Thesis, fully internal, Universiteit van Amsterdam], pp. 3-7.

[21] Saloul, I. A. M. (2009). Telling memories : Al-Nakba in Palestinian exilic narratives. [Thesis, fully internal, Universiteit van Amsterdam] , pp. 3-7.

[22]Vardhan, A. (2021, May 24). From pre-independence to 1990s: India’s stand on Israel-Palestine has been tightrope walk. Newslaundry. https://www.newslaundry.com/2021/05/24/from-pre-independence-to-1990s-indias-stand-on-israel-palestine-has-been-tightrope-walk

[23]Ibid.

[24]Global Trends 2030: Alternative Worlds. (2012). National Intelligence Council. https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/GlobalTrends_2030.pdf , pp75-77.

[25]Guha, S. (2023, October 19). Friend, She Is My Elder Sister’: Revisiting Yasser Arafat’s Ties With Indira Gandhi. Outlook. https://www.outlookindia.com/international/-friend-she-is-my-elder-sister-revisiting-yasser-arafat-s-ties-with-indira-gandhi-news-325476

[26] Stanly Johny, What is India’s Palestine position? The Hindu, Oct 23, 2023. news@newsalertth.thehindu.com

[27]https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/11/amid-war-middle-east-india-israel-ties-reach-new-milestone#:~:text=Only%20after%20the%20Oslo%20peace,to%20New%20Dehi%20in%202003.

[28] Sonia Gandhi, “A war where humanity is on trial now”, The Hindu, Oct 30, 2023, https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/a-war-where-humanity-is-on-trial-now/article67473719.ece

[29] USIP, op. cit.

[30] https://thediplomat.com/2023/10/a-changed-india-looks-emotes-and-thinks-like-israel/