Introduction

In the May 2024 issue of Policy Watch, we had presented a geostrategic perspective of India-China relations. In this follow-up piece, we focus on India’s relations with her remaining eight neighbours over the last decade.

When we take an integrated view of India’s relations with her neighbours, four aspects stand out. First is the element of continuity and change in India’s foreign policy in dealing with our neighbours where ideological underpinnings have largely given way to realpolitik of security and trade. Second is the overwhelming influence of the China factor impacting on our relationship with each of our neighbours. This involves the question of choice that our neighbours exercise based on their geopolitical and geostrategic compulsions. Third is the conflation of power, politics and people dimension manifesting in myriad ways with the potential to upend relations such as pandering to nationalist sentiments for electoral gains or responding to regime change, violent or otherwise. Finally, given the above three factors, what is the framework that should guide India’s relations with our neighbours for a mutually sustainable relationship?

Before we map India’s relationship with her eight neighbours, it may not be a bad idea to consider a very recent event. Leaders of Sri Lanka, the Maldives, Seychelles, Bangladesh, Mauritius, Nepal, and Bhutan were in New Delhi for the 9th June 2024 ceremony of the new government being sworn in. Writing for The Hindu, Suhasini Haidar quotes a press release by the Ministry of External Affairs which said that “this was in keeping with the highest priority accorded by India to its ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy and ‘SAGAR’ vision.”

The occasion also provided the Prime Ministers of Bangladesh and Bhutan the opportunity to hold bilateral talks with regard to Bangladesh’s desire to import hydropower from Bhutan, which requires a tripartite transit agreement with India, on the lines of a similar agreement discussed with Nepal. Haidar however noted that since New Delhi does not formally recognise the Taliban regime in Afghanistan, or the military regime in Myanmar, and does not maintain any high-level engagement with Islamabad, the grouping did not represent the entire neighbourhood, but only the countries in India’s “comfort zone”[1]. Nonetheless, we shall consider these three countries as well.

But before we proceed to country-specific details, it may be worthwhile to note the observation of Meera Srinivasan, senior assistant editor with The Hindu: “While Mr. Modi has called for ‘deeper people-to-people ties and connectivity in the region’, people in neighbouring countries evaluate India’s engagement based on many factors, not just financial assistance driven mostly by geopolitical insecurity. While nearly all neighbours value their friendship with India, they have not signed up for an uncritical embrace,

Afghanistan

India and Afghanistan share historical and cultural ties that have coloured much of the bilateral relationship. But the fly in the ointment has been the Taliban. The first Taliban regime (1996-2001) was not recognised by any country except by Pakistan, Saudi Arabia and UAE. For India, this period was especially painful. Just after it took control of Kabul, Taliban men had dragged the former Afghan president Najibullah — a close friend of India — out of the UN compound in which he had been hiding, tortured him and hanged him from the nearest lamp-post in the city.

Next was the 1999 hijacking of Indian Airlines flight 814. The plane was hijacked by five militants of the Harkat-ul-Mujahideen, an anti-India terror group then operating out of Pakistan and Bangladesh, and was flown to a number of locations in India before being diverted to Kandahar. The Taliban are believed to have thwarted any rescue attempt by the Indian government.

After the hijack of IC-814, then external affairs minister Jaswant Singh had to travel to Kandahar. “Singh took then Taliban foreign minister Muttawakil’s arm and traded three terrorists for the lives of the plane’s passengers and crew. One of those terrorists, Masood Azhar, would go on to establish the Jaish-e-Mohammed in Pakistan. That incident still haunts the Indian establishment.”[2]

Regime change and period of warmth and active friendship: In international relations, regime change – especially reflecting radical departures in ideological and economic frames – brings about significant shifts and reordering in bilateral relations. Events turned in India’s favour soon after the Taliban was bombed out by the US in 2001 following 9/11 and Hamid Karzai helmed the new Afghan government. By 2002, India had opened four consulates, apart from a mission in Kabul. How this came about is an interesting story:

“In the wake of the Bonn Agreement, when Kabul asked New Delhi to reopen its mission in Kabul and four more consulates, Pakistan protested. India is probably the only nation in the world to earn the abundant love and affection of the Afghans and Pakistan knows that. The relationship with the rest is largely fear, and sometimes awe.

Interestingly, the Americans protested too. US diplomats told their counterparts in India that Pakistan needed to be given another chance (it had been only one of three countries to have recognised the Taliban, besides Saudi Arabia and UAE), that it had influence in the region and that the US did not want to offend it by allowing India to establish its presence, especially in southern Afghanistan, a region Pakistan considered part of its own sphere of influence. Cushioned by what the Afghans wanted, India decided to spurn the Americans. Four consulates were opened.”[3]

If America wanted to appease Pakistan because “it had influence in the region”, there’s no gainsaying that India’s relations with Afghanistan would be impacted by Pakistan. Why Pakistan was against India opening four consulates and why this still happened may be gleaned from William Dalrymple’s captivating Brookings essay, “A Deadly Triangle: Afghanistan, Pakistan, and India”:

“After the Taliban were ousted by the U.S. after 9/11, a major strategic shift occurred: the government of Afghanistan became an ally of India’s, thus fulfilling the Pakistanis’ worst fear. The president of post-Taliban Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, hated Pakistan with a passion, in part because he believed that the ISI had helped assassinate his father in 1999. At the same time he felt a strong emotional bond with India, where he had gone to university in the Himalayan city of Simla, once the summer capital of British India. When I interviewed Karzai in Kabul in early March (2001), he spoke warmly of his days in Simla, calling them some of the happiest of his life, and he was moved almost to tears as he recalled the sound of monsoon rain hitting the tin roof of his student lodgings and the sight of the beautiful cloud formations drifting before his windows. He also expressed his love of Indian food and even admitted to liking Bollywood films. Karzai views India as democratic, stable and relatively rich, the perfect partner for Afghanistan, a “best friend” as he frequently calls it.”[4]

In the years afterward, India made wise use of its opportunity to forge a close partnership with Afghanistan. The aid and reconstruction program it set in motion during the 1980s was so generous that it quickly established India as the single largest donor in the country. Noted journalist and author, William Dalrymple says “it was also carefully thought out, praised as one of the best planned and targeted aid efforts by any country.”

India built roads linking Afghanistan with Iran so that Afghanistan’s trade can reach the Persian Gulf at the port of Chabahar, thus freeing it of the need to rely on the Pakistani port of Karachi. India donated or helped to build electrical power plants, health facilities for children and amputees, 400 buses and 200 minibuses, and a fleet of aircraft for Ariana Afghan Airlines. India was also involved in constructing power lines, digging wells, running sanitation projects and using solar energy to light up villages, while Indian telecommunications personnel built digitized telecommunications networks in 11 provinces. One thousand Afghan students a year were offered scholarships to Indian universities. India also played a key role in the construction of a new Afghan parliament in Kabul at a cost of $25 million. All this led to India becoming enormously popular in Afghanistan: an ABC/BBC poll in 2009 showed 74% of Afghans viewing India favorably, while only 8% had a positive view of Pakistan.

Violence as a “moderating” factor in bilateral relations: If about 2,500 US soldiers were to die in the killing fields of Afghanistan “fighting someone else’s war”, it was obvious that the Taliban, while it was ousted was very much a fighting machine, and it couldn’t have been so if it did not have strong sponsors and backers. Along with US, India started paying the price.

By 2008, the Indian embassy in Kabul was bombed, killing 40 and wounding more than 100. Fifteen months later, on October 8, 2009, a massive car bomb set off just outside the Indian embassy killed 17 people and wounded 63. Most of the dead were ordinary Afghans caught walking near the target. A few Indian security personnel were wounded, but the blast walls built following the 2008 attack deflected the force of the explosion, so that physical damage to the embassy was limited.

Less than six months later, on February 26, 2010, two of the Indian guest houses, the Park and the Hamid – which housed small Indian army English Language Training Team, and all the Indian army doctors and nurses staffing the new Indira Gandhi Kabul Children’s Hospital – were attacked by militants. The front portion of Hamid guesthouse was completely destroyed – there was just a huge crater. Everything had been reduced to rubble. A car bomb had rammed the front gate and leveled the front of the compound. Three militants then appeared and began firing at anyone still alive. In all 18 people were killed in the attack that morning, nine of them Indians, and 36 were wounded. Among the dead found beneath the debris was the assistant consul general from the new Indian consulate in Kandahar.

The Pakistan angle: According to Dalrymple, this consulate was a particular bugbear of the Pakistanis, who accused it of being a base for RAW—the Research and Analysis Wing, India’s external intelligence agency. The Pakistanis believed RAW was funding, arming and encouraging the insurgency in Baluchistan, the province that has been waging a separatist struggle ever since it was incorporated into the new nation of Pakistan in 1947.

Dalrymple contends that it was not difficult to figure out the motive for the attack. The operation was soon traced by both Afghan and U.S. intelligence to a joint mission by the Pakistani-controlled Haqqani network, a Taliban-affiliated insurgent group under the leadership of Jalaluddin Haqqani, and the Pakistan-based anti-Indian militant group Lashkar-e-Taiba (Army of the Righteous), which carried out the November 2008 assault on the Taj Hotel and other targets in Mumbai. Both the Haqqani network and Lashkar-e-Taiba are believed to take orders from the ISI—Inter-Services Intelligence, which is closely linked to the military. Pakistan made no public comment on the attack, other than to refuse permission for the planes.

Sleeping with the enemy: Maintaining relations with a country that had a new dispensation as an outcome of turbulent change and has had an adversarial relation with India, may be not just a tricky situation but a Hobson’s choice. Veteran journalist Jyoti Malhotra holds that over the years, as the Taliban morphed in and out of the Islamic State, Al-Qaeda, the Haqqani Network, Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s men and a variety of other terror groups that may or may not have owed allegiance to the Pakistani establishment, it became clear that “the need to keep your channels open with the Taliban were largely about gauging whether they would be an alternative source of power in Kabul.”[5]

Perhaps this was the reason why US special envoy for Afghanistan, Zalmay Khalilzad recommended that India start talking to the Taliban, in recognition of the fact that it was expanding its presence across the country. Maybe that’s why then Afghan president Ashraf Ghani was signing a new unity agreement with his former number 2, Abdullah Abdullah, having been persuaded by Khalilzad that the conjoined leadership should embark upon a power-sharing dialogue with the Taliban to bring about a permanent peace – even though Ashraf Ghani accused the Taliban to have intensified the war and for shedding Afghan blood.

The above is in line with the first lesson in diplomacy: Keep your friends close, but your enemies closer. But so far as India was concerned, in early April 2020, India shut down two out of the four consulates in Afghanistan – Herat in the west, ostensibly because of rising Covid cases, and Jalalabad in the south, the gateway to the Khyber because it was getting increasingly insecure for Indians to function from there. According to one analyst, this was a cruel blow for Indian interests as shutting down of the consulates was a “clear and grim reminder that Delhi’s South Block has little time to pay close and continuous attention to the goings-on in its neighbourhood once-removed. Perhaps, its mandarins would rather serve in the posher capitals of the West.”[6] Evidently, Pakistan was breathing a huge self-congratulatory sigh.

On 15 August, 2021, the Taliban regained control of Afghanistan as American troops withdrew from the country following a twenty-year “war against terror”. India’s response was swift. A press release dated August 17, 2021 read as such:

In view of the prevailing situation in Kabul, it was decided that our Embassy personnel would be immediately moved to India. This movement has been completed in two phases and the Ambassador and all other India-based personnel have reached New Delhi this afternoon.[7]

India now has a “technical team” in Kabul. While it continues to provide much-needed humanitarian assistance, especially wheat to Afghanistan, joint infrastructure projects remain stalled and e-visas have reportedly mostly been extended to Afghans from Hindu and Sikh faiths, New Delhi’s approach towards Taliban 2.0 seems a little unclear.[8] Meanwhile, India remains the largest regional contributor to Afghanistan’s reconstruction and development efforts with pledges of $3 billion.

According to Gautam Mukhopadhaya, former Indian Ambassador to Afghanistan “India’s position on the Taliban is the same as elsewhere in the region — which is to deal with the ‘reality’ of its current dominance so long as it is not anti-India, primarily for its security interests. It is a security-centric and realist policy in which it is trying to preserve its equities.”[9]

The Taliban also placed its own officials in over 14 diplomatic missions across the world such as in Iran, Turkey, Pakistan, Russia and China. But the power struggle in the Afghan embassy in Delhi — between the Taliban and Afghanistan’s previous democratic government — shows how it hasn’t been successful everywhere. On 24th November 2023, the Embassy of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (not to be confused with Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the new name of Taliban government) announced permanent closure in New Delhi. The embassy blamed both the Taliban rulers in Kabul as well as the Government of India for pressuring it to stop operations in India permanently. The embassy had stopped functioning on September 30 when the senior Afghan diplomats and the ambassador representing the Government of Islamic Republic of Afghanistan left India.

India has not recognised the Taliban administration in Kabul and it has not restarted full-scale diplomatic activities at its embassy in Kabul after closing it in August 2021. The permanent closure of the embassy of Afghanistan will create a challenging situation for traders and travellers who want to apply for Afghan visas. That apart, it also severs the formal link that India had with the ruling elite of the previous government headed by Dr. Ashraf Ghani.[10]

How intelligent is India’s response in the unfolding scenario? From dire forebodings in 2021 when the Taliban came to power to 2024, New Delhi has come a long way in Kabul. On Jan 29, 2024, the Taliban administration in Afghanistan hosted a meeting titled ‘Afghanistan Regional Cooperation Initiative’ in the Afghan capital. The meeting was addressed by the Taliban Acting Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi and was attended by representatives from neighbouring and regional countries. An Indian delegation participated in this meeting which was the first international meeting hosted by the de facto authorities in Afghanistan since they seized power in Afghanistan on August 15, 2021.[11]

A few days later, the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) reiterated India’s relation with the Afghan people and acknowledged that Indian diplomats have been engaging the Taliban on “various formats”, although India has refused to recognise the Taliban government and has a “technical team” at the Embassy in Kabul catering only to the humanitarian requirements of the Afghans. While India has remained cautious, China has increased diplomatic engagement with Kabul as represented by the exchange of envoys between Kabul and Beijing. On January 30, 2024, President Xi Jinping of China accepted the letter of credential of Taliban’s official Ambassador to China, Mawlawi Asadullah.

So, what could this diplomatic pirouette be attributed to? Is it because of Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, Afghanistan’s Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs since 7 September 2021? “Stanikzai is certainly an important factor. He is an important member of the Taliban and like many, who have had connections with India, is aware of the Indian ethos and culture. He would know that India has no territorial ambitions, and that New Delhi is a contributor to the development of Afghanistan,’’ says Ashok Sajjanhar, former Indian ambassador to Kazakhstan, Sweden, and Latvia.

It is reported that Stanikzai has old India connections. He trained as a soldier at the Army Cadet College of the Indian Army at Nowgaon in India for three years from 1979 to 1982 under an Indo-Afghan cooperation programme. Stanikzai, an ethnic Pashtun of the Stanikzai sub-tribe, also spent time as an officer cadet for a year-and-a-half with the Keren Company of the Bhagat Battalion at the IMA, Dehradun, one of 45 foreign cadets in the Keren Company.

According to Sajjanhar, “India has a half-way house in Kabul and the threat of terror attacks on India at the behest of Pakistan from the Afghan soil have receded. In fact, relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan have soured. India remains the largest regional donor for Afghanistan with pledges amounting to $3-4 billion. In December 2022, Taliban’s Minister for Urban Development, Hamdullah Nomani, held talks with members of the Indian technical team in Kabul where he called for renewal of Indian projects, invited investment in New Kabul Town, raised visa issues and urged more scholarships for Afghan students.

On March 7, 2023 a high-level Indian delegation led by J P Singh, the joint secretary heading MEA’s division for Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran, met with Taliban foreign minister Amir Khan Muttaqi in Kabul – marking the first acknowledged meeting between senior officials after the shift of power in Afghanistan in August 2021. Singh also met with former Afghan president Hamid Karzai, officials from the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan (UNAMA) and members of the Afghan business community, Jaiswal explained during the weekly press briefing.

The development came after the embassy of Afghanistan in New Delhi that was earlier run by officials with affiliation to the pre-Taliban government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan was shut down and the consular responsibilities were taken over by Afghan officials who are considered to be pro-Taliban. The Afghan readout of the meeting highlighted that Singh commended the efforts of the Taliban in “ensuring overall security and stability, countering narcotics, fighting the ISKP and corruption in the country”[12]. On the other hand, the MEA’s briefing focussed on India’s humanitarian assistance to the people of Afghanistan and the use of Chabahar port by Afghan traders.

About two weeks later, Afghan consul generals in India — seen as the de facto “leaders” of the Afghan embassy in Delhi after a power struggle last year — met top officials from the Ministry of External Affairs (MEA) Saturday to discuss the status of bilateral fund – the India Afghanistan Foundation (IAF). This fund finances projects aimed at promoting scientific, educational, technical and cultural cooperation between the two countries. A 10-member board of directors, co-chaired by ambassadors from both countries, supervises the fund.

The meeting came shortly after US Special Representative for Afghanistan Thomas West’s visit to India earlier that week to discuss the situation in the Taliban-ruled country. He had met Foreign Secretary Vinay Kwatra and joint secretary Singh in Delhi. In a post on X, West acknowledged that “India continues to deliver critical humanitarian aid and medicine to the Afghan people, and we discussed 2024 needs. Also exchanged views on development of a unified diplomatic approach in support of collective interests.”[13]

These developments also came amid deteriorating ties between Pakistan and Taliban-ruled Afghanistan. Earlier that week, Pakistan carried out airstrikes in Khost and Paktia provinces of Afghanistan and the Taliban defence ministry said it carried out retaliatory strikes.[14]

In 2021 when the Taliban had come to power, naysayers had written off India with dire forebodings about the Islamic crescent at India’s frontiers and the threat of ISI-backed Taliban terrorists to wage a full-scale battle in Kashmir. While we do see India has taken many steps in dealing with the current Taliban government, in official circles it is recognised that “India (can) scarcely afford to let its guard down because of the presence of terror groups in Afghanistan, even though the situation in bilateral ties is much improved.”[15]

So far, the Ministry of External Affairs has not elaborated if India would follow the example of others who have established diplomatic relations with the Taliban-ruled Afghanistan, and grant de facto recognition.[16]

In contrast, on January 30, 2024, after over two years of negotiations, China recognised Bilal Karimi, a former Taliban spokesman, as an official envoy to Beijing, making Xi’s government the first in the world to do so since the group seized power in Afghanistan in 2021. While China clarified acceptance of diplomatic credentials did not signal Beijing’s official recognition of Afghanistan’s current rulers, Taliban’s isolation was ready to roll back. China’s action has a lesson for India.

At a time when Afghanistan’s Taliban rulers are treated as outcasts by much of the world, China has stepped up engagement with the group. News portal Al Jazeera reports that in 2023, several Chinese companies signed multiple business deals with the Taliban government. The most prominent among them was a 25-year-long, multimillion-dollar oil extraction contract with an estimated investment value of $150m in the first year, and up to $540m over the next three years. But this was made possible because China had been maintaining relations with the Taliban since the late 1990s even when it was considered a pariah by the almost the whole world.

We may conclude the section on India-Afghanistan relations by raising just two related questions: (a) how sensible and at what cost is New Delhi’s reluctance to engage meaningfully with actors inimical to its liking; and (b) is this a pattern that we shall witness vis-à-vis other countries?

Quo Vadis? To our mind, the first question we raised in the foregoing para contains the seeds of future course of action. Learning from our own actions and the actions of others – particularly China, the United States, Pakistan and of course, the Taliban – the pathway lies in robust engagement and not tentative dalliance. After all, the reserves of goodwill that India has among Afghans are deep and they don’t dry up easy.

After all, the most enduring way of normalising relations is strengthening people-to-people contact in myriad ways, humanitarian or cultural. Thousands have stayed long periods in our country, including Sher Mohammad Abbas Stanikzai, an important member of the Taliban and Afghanistan’s Deputy Minister for Foreign Affairs for over That India has no territorial ambitions is well recognised. three years now. And India still remains the biggest regional benefactor of Kabul with its aid efforts praised as one of the best planned and targeted aid efforts by any country.

So, India should do more of the same, use its soft power, and given its increasing economic might, pursue aid and development diplomacy with greater vigour. It has taken three years too long to find its bearings again. It’s time it moved to higher gear.

In this Feb 19, 1999, file photo former prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee waves from the maiden Delhi-Lahore bus service on his arrival at Lahore to attend a Summit in Pakistan

Pakistan

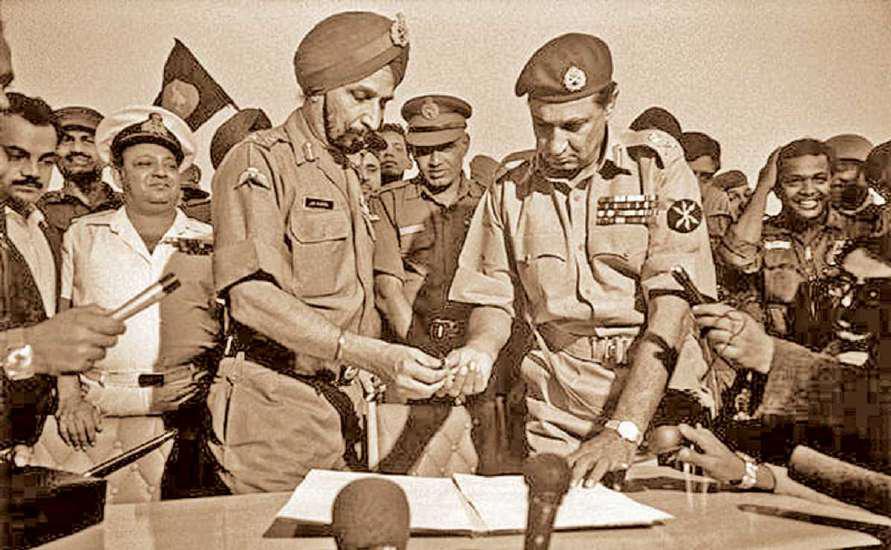

Our review of India-Afghanistan relations has indicated the long shadow that organised violence on Indian assets can cast. But unlike with Afghanistan, India has gone into war with Pakistan on three occasions: 1947, 1965 and 1971, apart from the Kargil war of 1999. In each of these battle encounters, Pakistan has had to pay a heavy price, including surrendering about 93,000 personnel after the 1971 war leading to the dismemberment of East Pakistan and the birth of independent Bangladesh.

Existential threat perception: While then Pakistan Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto did sign the Shimla Agreement in 1972, he was the same person who had declared “a thousand year war” against India in a speech in UN sometime in 1965. Five years after Bhutto signed the Shimla Agreement, he was deposed by his army chief General Zia ul-Haq in a military coup, and executed after a controversial trial. But Zia did implement Bhutto’s “thousand year war” with ‘Bleed India through a Thousand Cuts’ doctrine using covert and low intensity warfare with militancy and infiltration[17]

Normalising relations and the most famous attempt that soon failed: We mustn’t forget the most famous attempt at normalising relations and strengthening people-to-people contact. This was when Vajpayee took a bus ride and it seemed peace with Pakistan was possible. “Hum jung na hone denge … Teen bar lad chuke ladayi, kitna mehnga sauda… Hum jung na hone denge…” Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s words reverberated through Lahore as the Indian prime minister arrived in the city by bus on 19 February, 1999.

Writing for The Print, Nayanima Basu recalls that the ‘bus yatra’ was part of a confidence-building measure or CBM that both Vajpayee and his then Pakistani counterpart Nawaz Sharif had taken at the SAARC Summit in Colombo in 1998 in the aftermath of the nuclear tests that were carried out earlier that year by both neighbours that had sent shockwaves around the world. As a result, both leaders came under severe pressure from the international community, especially the US which threatened sanctions on both, that both countries have good neighbourly relations.[18]

Vajpayee went to extra lengths and made sure that he visited Minar-e-Pakistan, a symbolic icon of Pakistan’s creation, as part of this ‘bus diplomacy’ despite stiff resistance from the Pakistani security. Basu also quotes former Research & Analysis Wing (R&AW) chief A.S. Dulat’s book, Kashmir: The Vajpayee Years. Vajpayee not just visited the monument, he even wrote in the visitor’s book there: “A stable, secure and prosperous Pakistan is in India’s interest. Let no one in Pakistan be in doubt. India sincerely wishes Pakistan well.” Sharif on his part left no stone unturned to welcome Vajpayee, organising an event for Vajpayee at the Lahore Fort, which was carefully arranged by Salima Hashmi, then principal of the National College of Arts and daughter of poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz. Vajpayee and Sharif signed the Lahore Declaration in which both countries vowed to avoid conflict and committed to implementing the Shimla Agreement of 1972, recognising the Line of Control in Kashmir.

Within just three months of his historic initiative, India and Pakistan were embroiled in another jung — the Kargil War. In May 1999, Pakistani forces infiltrated the high mountains of Kargil district of Ladakh. By the time it was detected by the Indian Army patrols, the total area seized by the ingress was estimated to be between 130 and 200 sq km. India responded with Operation Vijay, a mobilisation of 200,000 Indian troops along with the Indian Air Force (IAF) launching Operation Safed Sagar in support of the mobilisation. The joint operations led to fierce fighting, involving heavy artillery, ground attacks in difficult terrain to recapture the peaks such as the Tiger Hill, and air support by the IAF. Eventually the infiltrators were pushed back and the war ended on 26th July 1999.

According to Dalrymple, for the Pakistani military, the existential threat posed by India has taken precedence over all other geopolitical and economic goals. The fear of being squeezed in an Indian nutcracker is so great that it has led the ISI to take steps that put Pakistan’s own internal security at risk, as well as Pakistan’s relationship with its main strategic ally, the U.S. Since the early 1980s, the ISI has funded and incubated a variety of Islamic extremist groups. Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid wrote there are currently more than 40 such extremist groups operating in Pakistan, most of which have strong links with the ISI as well as the local Islamic political parties. Pakistani generals have long viewed the jihadis as a cost-effective and easily-deniable means of controlling events. [19]

In the table below, we catalogue some of the prominent attacks on Indian assets and people by Pakistan[20]

| 1. | Dec 2000 | Red Fort stormed. 2 Indian military personnel killed. (Significant because attack carried out just 2 days after declaration of cease fire. |

| 2. | Oct 2001 | Car bomb explosion near J&K State Assembly. 27 killed |

| 3. | Dec 2001 | Indian Parliament attack |

| 4. | Sep 2000 | Attack on Swaminarayan Temple . 30 killed |

| 5. | July 2003 | Qasim Nagar market attack.at Srinagar. 27 killed |

| 6. | Aug 2003 | 2 car bomb attacks in Gateway of India and Zaveri bazar. 48 killed |

| 7. | Jul 2005 | Srinagar bomb attack near Indian Army vehicle. Suicide bomber among 5 other killed |

| 8. | July 2005 | Budhsha Chowk attack near City Centre, Srinagar. 2 killed, 17 injured |

| 9. | Nov 2008 | Also known as 26/11 attack, Mumbai lasting 4 days. A total of 175 people died, including nine of the attackers, with more than 300 injured.

Interestingly The Composite Dialogue between India and Pakistan from 2004 to 2008 addressing all outstanding issues had completed four rounds and the fifth round was in progress when it was paused in the wake of the Mumbai terrorist attack. |

| 10. | Feb 2010 | Two separate attacks in Pune and Sidda Camp attack in West Bengal, killing 17 1nd 28 people respectively |

| 11. | Jul & Sep 2011 | The Mumbai bombings took 28 lives; Delhi bomb attack claimed 15 lives |

| 12. | Feb 2013 | Hyderabad blasts claimed 18 lives |

| 13. | Mar 2015 | Terrorists attack police station in J&K.: 2 militants and 4 others killed |

| 14. | Jul 2015 | Gurdaspur attack. 3 3 gunmen in army uniforms open fire on a bus and then attack police station. 10 people killed, including the Superintendent of Police. |

| 15. | Jun 2016 | Pampore attack. 8 Killed. Carried out by LeT militants |

| 16. | Sep 2016 | Uri attack on army convoy. 18 killed; 20 imjured |

| 17. | Oct 2016 | Army camp attacked at Baramulla. 5 killed |

| 18. | Feb 2019 | Pulwama attack on CRPF convoy. 38 jawans killed |

Another assault; restrained response: On November 26, 2008, fears that India and Pakistan would once again head towards direct military confrontation abounded after militants laid siege to the Indian capital of Mumbai. Over three days, one hundred sixty-six people were killed, including six Americans. Both India and the United States blamed Pakistani-based Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), a militant group with alleged ties to the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI)—Pakistan’s primary intelligence agency—for perpetrating the attack. Although evidence suggested linkages between LeT and facets of the Pakistani government, India’s response was even-handed. Instead of escalating tensions, the Indian government took the diplomatic route by seeking cooperation with the Pakistani government to bring the perpetrators of the attack to justice, paving the way for improved relations.

Shivshankar Menon, the former foreign secretary, provides an insider account on the restraints shown by the UPA government towards Pakistan after the terror attacks:

I am often asked, “Why did India not attack Pakistan after the 26/11 attack on Mumbai?” Why did India not use overt force against Pakistan for its support of terrorism? I myself pressed at that time for immediate visible retaliation of some sort, either against the LeT in Muridke, in Pakistan’s Punjab province, or their camps in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, or against the ISI, which was clearly complicit. To have done so would have been emotionally satisfying and gone some way toward erasing the shame of the incompetence that India’s police and security agencies displayed in the glare of the world’s television lights for three full days.

The then national security adviser, M.K. Narayanan, organized the review of our military and other kinetic options with the political leadership, and the military chiefs outlined their views to the prime minister. As foreign secretary, I saw my task as one of assessing the external and other implications and urged both external affairs minister Pranab Mukherjee and Prime Minister Manmohan Singh that we should retaliate, and be seen to retaliate, to deter further attacks, for reasons of international credibility and to assuage public sentiment.

For me, Pakistan had crossed a line, and that action demanded more than a standard response. My preference was for overt action against LeT headquarters in Muridke or the LeT camps in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir and covert action against their sponsors, the ISI. Mukherjee seemed to agree with me and spoke publicly of all our options being open. In these discussions we considered our options, the likely Pakistani response, and the escalation that could occur.

But on sober reflection and in hindsight, I now believe that the decision not to retaliate militarily and to concentrate on diplomatic, covert, and other means was the right one for that time and place…

The choice of restraint: The simple answer to why India did not immediately attack Pakistan is that after examining the options at the highest levels of government, the decision makers concluded that more was to be gained from not attacking Pakistan than from attacking it. An Indian attack on Pakistan would have united Pakistan behind the Pakistan Army, which was in increasing domestic disrepute, disagreed on India policy with the civilian elected government under President Asif Zardari, and was half-heartedly acting against only those terrorist groups in Pakistan that attacked it. An attack on Pakistan would also have weakened the civilian government in Pakistan, which had just been elected to power and which sought a much better relationship with India than the Pakistan Army was willing to consider.

Zardari’s foreign minister, Shah Mehmood Qureshi, was actually visiting Delhi on the night the attack began. The Pakistan minister of information, Sherry Rehman, who admitted publicly that Kasab was a Pakistani, soon lost her job under pressure from the army. In fact, the Pakistan Army mobilized troops and moved them to the India-Pakistan border immediately before the attack began, then cried wolf about an Indian mobilization. Once again, a war scare, and maybe even a war itself, was exactly what the Pakistan Army wanted to buttress its internal position, which had been weakened after Gen. Pervez Musharraf’s last few disastrous years as president.

A limited strike on selected terrorist targets—say, the LeT headquarters in Muridke or the LeT camps in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir—would have had limited practical utility and hardly any effect on the organization, as U.S. missile strikes on al Qaeda in Khost, Afghanistan, in August 1998 in retaliation for the bombing of the U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania had shown. The LeT camps were tin sheds and huts, which could be rebuilt easily. Collateral civilian damage was almost certain since the camps, and particularly the LeT buildings in Muridke, had deliberately been sited near or beside hospitals and schools. Even if there were no civilian casualties from Indian actions, casualties could nonetheless be alleged and produced by the ISI. The real problem was the official and social support that terrorist groups in Pakistan such as the LeT were receiving, and that was not likely to stop because of such a limited strike. So this consideration was really irrelevant to the decision.

And a war, even a successful war, would have imposed costs and set back the progress of the Indian economy just when the world economy in November 2008 was in an unprecedented financial crisis that seemed likely to lead to another Great Depression.

Now let’s consider what did occur when India chose not to attack Pakistan. By not attacking Pakistan, India was free to pursue all legal and covert means to achieve its goals of bringing the perpetrators to justice, uniting the international community to force consequences on Pakistan for its behaviour and to strengthen the likelihood that such an attack would not take place again. The international community could not ignore the attack and fail to respond, however half-heartedly, in the name of keeping the peace between two NWS. The UN Security Council put senior LeT members involved in the attack on sanctions lists as terrorists.

The real success was in organizing the international community, in isolating Pakistan, and in making counterterrorism cooperation against the LeT effective. India began to get unprecedented cooperation from Saudi Arabia and the Persian Gulf countries, and China, too, began to respond to requests for information on these groups. Equally, success could be measured in dogs that did not bark in the night, in avoiding the outcomes that would have resulted from a decision to attack Pakistani targets and the high probability of war ensuing from such a decision.

All the same, should another such attack be mounted from Pakistan, with or without visible support from the ISI or the Pakistan Army, it would be virtually impossible for any government of India to make the same choice again. Pakistan’s prevarications in bringing the perpetrators to justice and its continued use of terrorism as an instrument of state policy after 26/11 have ensured this. In fact, I personally consider some public retribution and a military response inevitable. The circumstances of November 2008 no longer exist and are unlikely to be replicated in the future.[21]

Later Developments: In 2014, there were hopes that India would pursue meaningful peace negotiations with Pakistan after India’s then-newly elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi invited Pakistani Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to attend his inauguration. After a brief period of optimism, relations turned sour once more in August 2014 when India cancelled talks with Pakistan’s foreign minister after the Pakistani high commissioner in India met with Kashmiri separatist leaders. A series of openings continued throughout 2015, including an unscheduled December meeting on the sidelines of the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris. This was followed by a meeting between national security advisors in Bangkok a few days later, where the Kashmir dispute was discussed. In the same month, Prime Minister Modi made a surprise visit to Lahore to meet with Prime Minister Sharif, the first visit of an Indian leader to Pakistan in more than a decade.

According to Center for Preventive Action, Council on Foreign Relations, momentum toward meaningful talks came to an end in September 2016, when armed militants attacked a remote Indian Army base in Uri, near the LOC, killing eighteen Indian soldiers in the deadliest attack on the Indian armed forces in decades. Indian officials accused Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM), another group with alleged ties to ISI, of being behind the attack. In response, the Indian military announced it had carried out “surgical strikes” on terrorist camps inside Pakistani-administered Kashmir while the Pakistani military denied that any such operation had taken place.[22]

This period was marked by an uptick in border skirmishes that began in late 2016 and continued into 2018, killing dozens and displacing thousands of civilians on both sides of the Line of Control. In 2017, more than three thousand cross-border strikes were reported, while nearly one thousand were reported in the first half of 2018. Militants launched attacks in October 2017 against an Indian paramilitary camp near Srinagar and, in February 2018, against an Indian army base in the Jammu region, which killed five soldiers and a civilian.

In February 2019, an attack on a convoy of Indian paramilitary forces in Pulwama, killed at least forty soldiers. The attack, claimed by the Pakistani militant group JeM, was the deadliest in Kashmir in three decades. India retaliated by conducting an air strike that targeted terrorist training camps within Pakistani territory; these were answered by Pakistani air strikes on Indian-administered Kashmir. The exchange escalated during which Pakistan shot down two Indian military aircraft and captured an Indian pilot; the pilot was released two days later.[23] In February 2021, India and Pakistan issued a joint statement for to a strict observance of all agreements, understandings and cease firing along the Line of Control (LoC) and with effect from the midnight of Feb 24, 2021.

Looking into the Future: Since 2019, diplomatic relations between the two neighbours have been especially strained. In response to the Indian abrogation of Article 370 that year, Pakistan downgraded its diplomatic ties with India and halted trade between the two countries. At present, India and Pakistan have vacant positions for high commissioners, and both countries have appointed deputy high commissioners and charge d’ affaires respectively in each other’s countries.

In a realistic yet forward looking article in The Diplomat, Khurram Abbas and Mohammad Khan[24] see both scope and hope in improving India-Pak relations. They do note the prerequisites that both sides place on each other: EAM Jaishankar’s statement that that India is open to dealing with Pakistan but not under conditions where terrorism is seen as a legitimate tool for diplomacy; likewise, Islamabad has conditioned talks on the undoing of abrogation of Article 370. Yet Abbas and Khan also identify two factors – though small by itself – that are indicative of an improved relationship.

First is the strict compliance with the understanding between the two countries in 2023 on ceasefire. Second, in 2023, despite a severed diplomatic relationship between the two countries, Pakistan issued close to 7,000 visas to Indian Sikh and Hindu pilgrims to visit Pakistan to attend various religious festivals and occasions. Similarly, the release of roughly 500 Indian fishermen and 9 civilians was also reassuring.

So given the present two “bright spots” and some of the positives of the past, one can look forward to incremental confidence building measures in trade, travel and tourism. These could be followed up in collaborative efforts on matters such as combating the fallout of climate change in the Indus Basin, and addressing HDI issues. Pakistan is suffering as much India is from the scour of terrorism. It would take a little of a Vajpayee on both sides to move forward. If the experience of the global community with Taliban is any indication, hope lies in India-Pak relations too.

Maldives

If we stick to the geopolitical and geostrategic frame employed in this paper, then Maldives’ “India Out” campaign contains sufficient material to enable us to have a nuanced understanding of India-Maldives relations.

According to an analyst, the anti-India sentiment didn’t just sprout overnight in 2020, but is nearly a decade old and can be traced back to when Abdulla Yameen Abdul Gayoom of the Progressive Party (PPM) became president in 2013.[25] She quotes Dr. Gulbin Sultana, a research analyst at the Manohar Parrikar Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, whose area of research includes the Maldives to inform us that India-Maldives relations deteriorated during the PPM’s five-year rule and the anti-India sentiment was apparent even back then: “A lot of anti-India rhetoric was used during that time because the Maldivian government was pro-China”.

But it would be an oversimplification of diplomatic relations between the two countries to say that the Yameen government and its predecessor, the Waheed government, were “anti-India”. Although the Yameen government’s tilt in favour of China was clear, it had also openly discussed an ‘India-First’ policy for the Maldives. Still, there were some specific issues that have agitated sentiments against the Indian government in the Maldives. The first is the long-standing controversy over the two Dhruv Advanced Light Helicopters (ALF) that were given by India to the Maldives in 2010 and in 2015, both of which were used for ocean search-and-rescue operations, maritime weather surveillance and for airlifting patients between islands, and were based in Addu Atoll and at Hanimaadhoo.[26]

These helicopters were for humanitarian purposes only, but some in the anti-India constituency, particularly Yameen’s party PPM, were trying to portray that by gifting these helicopters, India was creating military presence in the country because they were military choppers.

According to the terms of bilateral agreements between the two countries, Indian officers had been sent to the Maldives to train the Maldives National Defence Force, under whose command these helicopters operate. When domestic fervour against the perceived military presence of Indian forces in the country reached its peak in 2016, the Yameen government had asked India to take back these gifted helicopters and refused to extend the term of the agreement that would extend their stay and use in the country. One of the main reasons behind the ‘India Out’ campaign was rooted in this controversy surrounding the ALF choppers and India’s reported refusal to take them back.

By 2018 when Ibrahim Mohamed Solih assumed office, he immediately re-signed these agreements, extending the stay and use of these choppers in the country. The Solih government’s visibly warm relations with India had only served to fuel anti-India sentiment in the country, Sultana explained.

“Contrary to what you may read… sometimes, it’s not as much as India with the current administration and PPM being pro-China. It’s far from it. We’ve had good relations with India as well. But the sort of relations that this government has, has transcended what we believe to be normal diplomatic and development ties,” Mohamed Shareef, vice-president of PPM is reported to have said: “While we welcome India being a very close development partner, the issue arises when certain boundaries are overstepped, particularly when it comes to sovereignty, national defence issues, and the government in particular has opted at times to keep the relationship under wraps which is where the criticism stems from.”[27]

Among the many grievances of prominent members of ‘India Out’ campaign, a recurring complaint was the lack of transparency in agreements being signed between the Solih government and India. Specifically, the demand was to share the terms of the agreement in the Parliament, which was not done on grounds of national security. This may seem strange, if not absurd, for why wouldn’t you share details if the issue related to humanitarian and non-strategic matters.

Sultana agrees that much of the criticism leveled by the Maldivian opposition and the ‘India Out’ campaign wouldn’t have arisen had these bilateral agreements been publicly discussed in the Maldives Parliament. But the ruling government and the defence ministry saying that these agreements are confidential led to agitation in political circles that percolated down to ordinary Maldivian nationals and took the form of a wave of criticism, inflammatory rhetoric and unverified allegations, especially on social media platforms.

A lot has happened in the two years since the Solih government came to power, Shareef agreed and that is reflected in the wide-ranging criticisms and accusations levelled at the Indian government in the Maldives. He points to the UTF Harbour Project agreement signed between India and the Maldives in February 2021, that first came about during the Yameen government, where India was to develop and maintain a coastguard harbour and dockyard at Uthuru Thilafalhu, a strategically located atoll near the capital Malé. In 2016, an Action Plan between India and the Maldives was signed for ‘defence cooperation’ to enhance “shared strategic and security interests of the two countries in the Indian Ocean region”. After the Solih government came to power, in 2019, local Maldivian media speculated that this UTF project would be turned into an Indian naval base.

Shareef told the Indian Express that leaked documents had shown that the agreement involved “the Indian military staying back here for decades and decades and having exclusive rights over using” the UTF facility. “We occupy such a large area of the Indian Ocean, it seems there is a tug of war going on over the Indian Ocean, and we are right in the middle of it,” Shareef added. “When we say we don’t want Indian military presence, we are really saying that we don’t want any foreign military personnel in the country. No other country has any military presence in the country—not even China,” said Ahmed.

Researchers say that the issue is complex and involves bilateral relations, geopolitical interests and economic arrangements for both countries. During the Yameen government, India had looked on in concern as the Maldives began to develop stronger ties with China and its Belt and Road Initiative. “We are against the permanent stationing of military presence in the Maldives, even the stationing of military equipment. So that is what the (India Out) movement is about. We also demand that India not interfere in domestic affairs,” Ahmed added.

“Any sort of military presence on our soil is not welcome and it is not welcome by a vast majority of Maldivians and these agreements have given India that right. We are going to annul these agreements because they don’t conform to our Constitution and sadly, we’re going to have to ask the Indian military to leave the day the government changes, which is going to be in another two years,” Shareef said.

Parliamentary Group leader of Maldivian Democratic Party (MDP), MP Ali Azim however, believes that the anti-India campaign is the result of the Solih government’s “hesitancy to take swift and firm action” against “groups of people are currently operating at their whim”. “The ‘India Out’ campaign is a false and dangerous narrative being promoted by groups of a few individuals through media platforms, both traditional media and social media, trying to fuel negative and vilifying perceptions about India. I believe this is the same group of people who are desperately trying to instill fear and use public emotions to character assassinate current leaders, using various religious slogans,” Azim told IndianExpress.com.

“What we are currently witnessing is the newfound freedom of expression being deliberately abused by few in our society. They are actively involved in defaming, slandering and even inciting violence against current leaders, institutions and even foreign countries,” Azim said of the ‘India Out’ campaign.

How does the Indian government view the “India Out” campaign in Maldives?: There have been two distinct strands of response. In June 2021 when the “India Out” campaign was at its peak, India’s high commission in Malé asked the Maldivian government to take steps to protect the high commissioner and diplomatic personnel from “malicious” and “personal” articles in the local media. A note verbale from the Indian high commission to the Maldivian foreign ministry, dated June 24, was accessed and published in the Maldivian media.

In the letter India complained about “recurring articles and social media posts attacking the dignity of the High Commission, the Head of the Mission, and members of the diplomatic staff by certain sections of the local media… These attacks are motivated, malicious and increasingly personal” and it requested the Maldivian government to ensure the protection of India’s diplomats to “prevent any attack on his/their person, freedom and dignity, and prevent any disturbances to the peace of the Mission or impairment of its dignity in accordance with relevant articles of the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations (1961)”. Besides, the high commission also called for action “in accordance with International Law and Maldivian Law, against the perpetrators for these gross violations of the Vienna Convention”.[28] Such charges and calls for action were viewed by many in Maldives as clear evidence of Indian interference in internal matters of Maldives.

On the other hand, External Affairs Minister, S Jaishankar has been quite upfront on this matter, to the point of appearing sanguine. During an interactive session with students of Indian Institute of Management, Mumbai, he said there are problems in every neighbourhood, but ultimately “neighbours need each other”. And being a major economy, China will deploy resources and try to shape things in its way, adding, “why should we expect otherwise, but the answer to that is not to complain that China is doing it.” Jaishankar also distinguished between political posturing and diplomacy. While sharp positions are taken in politics, diplomacy does not always go by those sharp positions. “At the end of the day, neighbours need each other. History and geography are very powerful forces. There is no escape from that,” he added.[29]

Reset in relations: So far as Maldives-India relations are concerned, Muizzu set about to do four things. The first three were like waving the proverbial red rag to India, while the fourth was aimed at seeking concession from India. First, he insisted India withdraw 76 military personnel by 10th May 2024 and replace them with civilian personnel to operate the two helicopters and one Dornier aircraft gifted by India. Second, his first port of call on assuming office was China and not India – a definite departure from tradition. Third, he inked twenty agreements with China that included financial and military assistance. Fourth was his request to India to extend the repayment deadline for $ 150 million of a $ 200 million debt. The loan was secured by the previous government upon assuming office in 2019.[30]

According to Professor Rajesh Rajagopalan, that smaller countries such as the Maldives or others would be tempted to play the China card should not be surprising. He says, it is logical, rational, and represents the kind of self-interested behaviour that New Delhi frequently invokes, such as in its relationship with Russia or Iran. Responding to such strategic ploys by Male with hyper-nationalism is counterproductive. Thankfully, this has been largely confined to India’s media and social media warriors from whom nuance is hardly to be expected. Obviously, absurd social media comments by Maldivian officials need to be countered, and the official Indian response was largely the correct one. It was a self-goal by Male that put it on the defensive, and official New Delhi’s relatively restrained reaction underlined this fact.[31]

Muizzu in turn does not want to replace India with China, but rather seeks to use the two countries’ tenuous relationship as leverage to secure the best deal. The Maldives is still part of Modi’s “Neghbourhood First” foreign policy strategy, which aims to bolster relations with India’s geographic neighbours. Under this doctrine, New Delhi loaned Malé $500 million for road and bridge projects in 2021 and announced a $100 million line of credit in 2022 to support development initiatives, including for cybersecurity and affordable housing.

Bangladesh

If trade, commerce and other facets of relationship between India and Pakistan have reduced to a trickle because of Pakistan’s never-ending support of cross-border terrorism, the story of India’s relationship with our eastern neighbour Bangladesh is exactly the opposite. If we were to go to a branded shop to buy a shirt, chances are it would have been made in Bangladesh. This is an indication of the type and volume of bilateral trade between India and Bangladesh which was about $6.6 billion. There are estimates that the trade potential is at least four times more. However, quoting a PTI newsfeed, The Hindu reported that the bilateral trade has dipped to $14.2 billion in 2022-23, from $15 billion in 2021-22.[32]

In the first half of FY2024-25, India exported Rs 43,455 crore worth of merchandise to Bangladesh and imported Rs 8142 crore of merchandise from Bangladesh, resulting in a positive trade balance of Rs 35,313 crore or about $ 420 million. In the previous year too, exports of India increased by 18.5%, while imports decreased by 11.8%.[33] The five countries for import into Bangladesh in 2022-23 were China (21.5%), India (12.2%), Hong Kong (5.5%), Singapore (5.2%) and Indonesia (4.6%). [34] If we club Hong Long and China, the total imports by Bangladesh from there are over double from neighbouring India. In terms of exports from Bangladesh, India was nowhere among the top partners. The top five were the US (19.4%), Germany (14.7%), UK (11.0%), Spain (5.8%) and France (5.5%). This is not surprising since Bangladesh’s top export items were readymade garments.

Economic and people-to-people cooperation: If we were to restrict our overview to the last decade, the appropriate place to begin would be with late Sushma Swaraj, then Foreign Minister of India. In June 2014, during her first official overseas visit, various agreements were concluded to boost ties. These included:

- Easing of Visa regime to provide 5-year multiple entry visas to minors below 13 and elderly above 65.

- Proposal of a special economic zone in Bangladesh.

- Agreement to send back a fugitive accused of murder in India.

- Provide an additional 100 MW power from Tripurs.

- Increase the frequency of Maitree Express and start buses between Dhaka and Guwahati and Shillong.

- Bangladesh allowed India to ferry food and grains to the landlocked Northeast using its territory and infrastructure.

During Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s state visit to Bangladesh during June 2015 as many as 22 agreements were signed by two sides:

- US$2 billion line of credit to Bangladesh and a pledge of US$5 billion worth of investments.

- India’s Reliance Power to invest US$3 billion to set up a 3,000 MW LNG-based power plant (which is the single largest foreign investment ever made in Bangladesh).

- Adani Power to set up a 1600 MW coal-fired power plant at a cost of US$1.5 billion

- Maritime safety co-operation and curbing human trafficking and fake Indian currency.[35]

Following this, at midnight on 31 July 2015, around 50,000 people became citizens of India or Bangladesh after living in limbo for decades. Ending a prolonged dispute, the two nations swapped 162 enclaves on the border region, allowing the people living there to stay or opt out to the other country.

Inherent strains: When geospatial issues are involved that have a bearing on core interests of neighbouring countries, resolution can be a tricky matter. An ideal example relates to sharing of waters of Teesta river that impacts on the livelihoods and environmental concerns of two countries. In a federal structure like India, the concerned state government’s – here, West Bengal – legitimate stand can make negotiations complicated to the point of stalling any agreement. While a fairly detailed account has been presented by The Hindu explaining what is holding up the Teesta treaty[36], we may flag the core issues.

The stalled Teesta treaty surfaced recently when during the recent state visit of Sheikh Hasina, Prime Minister of Bangladesh, to India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi on June 22 said: “A technical team will soon visit Bangladesh to discuss conservation and management of the Teesta river in Bangladesh”, focussing “more about the management of the water flows within Teesta (and) less about water sharing per se”.

The remark triggered fresh speculation about the Teesta water sharing treaty with Bangladesh, a key bilateral agreement that has been pending between the two countries for over a decade. West Bengal Chief Minister, Mamata Banerjee, pointed out that if Teesta’s water is shared with Bangladesh, lakhs of people in north Bengal will get severely impacted, and had added “If I had the ability, I would have definitely shared Teesta waters with them.” In 2017, the Chief Minister had also referred to an alternative proposal of sharing waters of the Torsa, Manshai, Sankosh and Dhansai rivers but not Teesta.

In all, 54 rivers flow between India and Bangladesh and sharing of river waters has been a key bilateral issue. India and Bangladesh agreed on the sharing of waters of the Ganga in 1996 after the construction of the Farakka Barrage and by the 2010s the issue of sharing of the Teesta came up for negotiation. In 2011, during the United Progressive Alliance-II government, India and Bangladesh were close to signing an agreement on the Teesta but Ms. Banerjee walked out of the deal, and since then, the agreement has been pending.

Interestingly, the Ganga water sharing treaty with Bangladesh completes 30 years in 2026 and a renewal of the agreement is on the cards. The Trinamool Congress chairperson has pointed out that water sharing with Bangladesh has changed the Ganga’s morphology and affected lakhs of people in West Bengal owing to river erosion.[37]

Defence Cooperation: Bangladesh does not share a border with China. But that has not stopped China to have an almost three times bilateral trade than what Bangladesh has with India. Chinese investments in Bangladesh far outstrips India’s. It would therefore not be surprising if Chinese defence relations with Bangladesh outstrips India’s.

According to a detailed write-up on India-Bangladesh defence cooperation, it appears India has been wary of the Sino-Bangladesh defence relationship, and the purchase by Bangladesh in 2013 of two submarines from China hastened the demand by security analysts to cement the bilateral ties.[38] There was talk of a comprehensive bilateral defence cooperation agreement being signed during PM Hasina’s visit to India in April 2017. This was met with reservation—even scepticism—from Bangladesh, for reasons outlined below.

- A defence agreement with India would upset China, a major partner in the areas of defence and development. China is the only country with which Bangladesh has a formal defence cooperation agreement, though this has mostly gone unnoticed by the majority in Bangladesh.

- The agreement would be an infringement on Bangladesh’s sovereignty and would restrict its strategic autonomy. The India–Bangladesh Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Peace, 1972 is often used as an example to support this argument.[39]

During Prime Minister Hasina’s 2017 visit to India, the two countries signed a series of agreements and MoUs in areas of defence cooperation in the field of strategic operational studies, a line of credit worth US$500 million for the purchase of defence equipment, and coast guards of the two countries. While India was sceptical about the signing of an MoU instead of an agreement, according to analysts, a comprehensive defence pact may not find easy acceptability but MoUs will create opportunities for expanding defence cooperation in the future.

Before that, however, it is important to discuss the India–Bangladesh Friendship Treaty, traditionally viewed as a defence pact, and understand why it failed. While it was a comprehensive and wide-ranging document, and included other areas such as art and literature yet, the treaty was mostly considered a security and military pact, since the important provisions were in these areas: the two countries would not enter into any kind of military alliance against each other; they would refrain from aggression against one another; and they would restrict the use of their territories against the other. Additionally, the treaty indicated that the two countries would jointly deal with any third party that would threaten the security of either one.

The treaty, instead of cementing the relationship, added to the apprehensions and resentment of the Bangladeshi people, fuelling suspicions about India’s intentions in their country. The Bangladeshi defence forces also felt that the treaty undermined their importance.

The assassination of Mujibur Rahman in 1975 was a game changer: it transformed the dynamics of the relationship, which in turn affected the implementation of the treaty. The treaty completed 25 years in 1997, when the Awami League was the ruling party. Despite its India-friendly image, Bangladesh showed reluctance in renewing the treaty. India did not pursue the matter either, and the treaty simply lapsed.

Countering Terrorism: India and Bangladesh share more than 4,000 km of porous borders. They have shared history, culture and language, all adding to the relationship. Both countries understand that incidents in one country have ramifications across the border. Thus, the solution lies not in conflict but in cooperation. The issue of militancy is a case in point. Despite punitive actions taken by the Bangladeshi government, militancy continues to be an issue largely because of the cross-border network of radicalised groups that threaten the security of both countries and the entire region. The need to increase security and defence cooperation is driven by this convergence of interests.

Counter-terror cooperation is an important aspect of the defence relationship between India and Bangladesh, as both countries have been victims of terrorism and continue to face evolving security threats. India is subject to cross-border terrorism from groups based in Pakistan, and these groups use Bangladesh as a transit point into India. Meanwhile, Bangladesh suffers acts of terror committed by indigenous organisations with external linkages. The veterans of the Afghan Jihad established Harkatul Jihad Bangladesh in the 1990s. The terrorist organisations started to make their presence felt by 2000. Although Bangladesh pursues a policy of zero-tolerance towards terrorism and has undertaken strict counter-terrorism measures, including the execution of top leaders of Jamaat-ul Mujahideen Bangladesh (JMB) in 2007, terror groups have managed to survive in its territory because of the cross-border network, especially in India.[40]

To address these threats effectively, there is need for greater synergy, coordination and cooperation between agencies, joint training and exercises, greater interaction and understanding among the armed forces of the two countries.

Domestic issues; bilateral relations: In 2019, the Indian Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) following which Bangladesh’s Foreign Minister and Home Minister cancelled their trips to India. Later, another minister, Shahriar Alam also cancelled his visit to India. Bangladeshi Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was critical of the CAA, describing it as “not necessary”, but nevertheless affirmed CAA and the National Register of Citizens were “internal matters” of India. But when India had effected the Nepal blockade in 2015, Bangladesh Commerce Minister was critical of India’s action, stating that blockades hit at agreements like the BBIN because the agreement was created for the regulation of passenger, personal and cargo vehicular traffic between Bangladesh, Bhutan, India and Nepal (BBIN) to boost economic growth in the region.

In 2023, Bangladesh backed India in its diplomatic feud of India with Canada over the killing of Hardeep Singh Nijjar, describing Canada as a “hub for murderers”.

Sometimes however, issues can take an ugly turn. As one analyst has pointed out that remarks from among the political class which alluded to the supposed one crore undocumented Muslims immigrants in West Bengal who are “thriving” on the government’s Rs 2 per kg subsidised rice and are involved in arson should have been censured for their lack of sensitivity by the larger political establishment. And statements like “half of Bangladesh will be empty (vacant) if India offers citizenship to them (Bangladeshis)” reek of an arrogance that is distasteful in its implications. In the face of these repugnant announcements by politicians, it becomes difficult for the leaders of our neighbouring nations to consider warmer relations.[41]

India Out campaign: After Maldives, Bangladesh is also witnessing an “India Out” campaign. While the above distasteful statements of powerful members of India’s ruling elite may have no cause and effect relationship or even a correlation with the “India Out” campaign, it might help us understand why far-right leaders tend to arouse ultra-nationalistic and jingoistic sentiments for political ends.

According to SNM Abidi New Delhi’s stakes are many times bigger and higher than in the tiny Indian Ocean state. The hard-hitting campaign in Maldives cost our close and dependable ally Ibrahim Mohammed Solih the presidency and installed the China-leaning Mohamed Muizzu, who is cold-bloodedly taking the island nation into Beijing’s orbit and proving to be more than a handful for our overworked diplomatic and security establishments.[42]

The “India Out” campaign exhorts Bangladeshis to meticulously boycott all Indian products imported and sold in the country in order to teach New Delhi a “lesson”. The movement kicked off barely 10 days after Awami League’s Sheikh Hasina was sworn in as Prime Minister for a fourth straight term in a blatantly one-sided election, with its sponsors accusing India of keeping her in power to serve its own political, strategic and economic interests at the cost of Bangladeshis, imperilling democracy and Bangladesh’s sovereignty.

Start of the ‘India Out’ Movement: The movement is the brainchild of a Bangladeshi doctor, Pinaki Bhattacharya, an unrelenting Hasina critic living in exile in Paris since 2018, who has over two million followers on social media platforms. The activist openly says that Hasina has been conducting farcical elections since 2014 with “India’s covert and overt backing”, and until India’s economic interests are badly hurt it will keep meddling in Bangladesh’s internal affairs and supporting her. His very first video on his YouTube channel advocating boycott of Indian products garnered a million views. Subsequently, the opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party, human rights groups and civil society organisations threw their considerable weight behind the social media influencer’s drive.

Abidi says that while our media is somehow shy of reporting the impact of “India Out” movement, but soon after it was launched Voice of America quoted employees of shops in Dhaka and Chittagong saying that they had a seen a drop in the sale of Indian products like cooking oil, processed foods, toiletry, cosmetics and clothing. Similarly, Al Jazeera reported how suppliers for the Indian consumer goods giant, Marico, were facing a chilly reception in Dhaka, with grocery shops, usually eager to stock their shelves with its hair oil, cooking oil, body lotion and other products, refusing to take new deliveries – and a shopkeeper complaining that “Indian products just aren’t moving; we’re stuck with unsold stock and won’t be restocking.”[43]

Even more worrying is Nikkei Asia’s coverage of the campaign hitting Ramadan sales in the predominantly Muslim country prior to Eid: a “serious boycott” with customers specifically inquiring whether the products are Indian before purchasing – something which had never happened before – and shops cutting the prices of Indian imports to boost dwindling sales.

Abidi feels this is no laughing matter. If the campaign intensifies and there is indeed a sharp drop in the import of food, fuel, fertilisers and raw materials for industry from India, China stands to gain as Bangladesh will invariably turn to it as a substitute for Indian exports. And we all know of Chinese expertise in converting the gains from trade into military muscle.

But the anti-India wave that swept Bangladesh recently is nothing new. On June 10, 2022, thousands of people marched in Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh, to protest derogatory comments made by Nupur Sharma, a spokesperson of India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) about Prophet Muhammad. Angry protesters urged Muslim-majority nations to cut ties with India and boycott its products unless she was punished for defaming Prophet Muhammad. Unlike the governments of other Muslim-majority countries, Bangladesh’s Awami League government has remained silent on the offensive comments made by the BJP leaders.

Finally, Abidi suggest that we can defuse the “India Out” movement by engaging with the whole spectrum of political parties and civil society in the neighbouring country instead of cultivating only Hasina who anyway wears her allegiance to India on the pallu of her exquisite saris. Keeping all our eggs in one basket is hardly in our national interest. Let’s be flexible, pragmatic and not wear blinkers blindsiding us.[44]

Ali Riaz, a political science professor at Illinois State University, however provides an altogether different perspective to the “India Out” campaign. He thinks that there is a political message underpinning this campaign that has implications beyond immediate success. “The campaign reflects the simmering discontent about India’s disregard to the legitimate grievances of Bangladesh and its role in Bangladesh’s domestic politics”[45] And this has resonance with what Pinaki Bhattacharya, the exiled Bangladeshi physician and influential social media activist living in Paris and the star campaigner of the “India Out” had to say: the “India out” campaign harbours ‘‘no animosity towards the people of India”. “It is a vehement political fight aimed squarely at the governing elite of India, a relentless battle to reclaim the sovereignty and stewardship of our cherished motherland”.[46]

According to Partha S Ghosh, much of the blame for anti-India sentiments can be laid at the door of the current Home Minister. He says, “Of late, foreign policy loaded statements or actions emanate routinely from the offices of the Union home minister Amit Shah and the National Security Adviser Ajit K. Doval thereby systematically marginalising the assigned role of the Minister of External Affairs, S. Jaishankar. It seems his only job now is firefighting. The case of Bangladesh provides the most recent example. If one single person has to be identified who is solely responsible for vitiating the Bangladeshi popular mind against India, it is Amit Shah. His election rallies, whether in Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, Rajasthan, or northern India at large, irreparably damaged India-Bangladesh relations.”[47]

The aftermath of Hasina’s re-election and job-quota protests: Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina secured a fourth consecutive term in power earlier this year, with her Awami League party taking three-quarters of seats in parliament. Many observers termed the elections controversial, with the US saying it was neither free nor fair. The Election Commission too added to the confusion: it initially announced 27% voter turnout at its afternoon press briefing but later increased it to 41.8%, expressing the difference to lack of real time data.[48]

Two sets of facts are however uncontested. One, the vote was conducted by keeping almost all top leaders of the main opposition party and over 25,000 of its activists behind bars who were arrested in the run-up to the election on various charges—including arson attacks and vandalism—that some independent observers think were politically motivated. And two, while the major opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) and its allies did sit out the election, not all opposition parties followed suit. Out of forty-four registered parties, twenty-seven fielded candidates. Additionally, nearly 1,900 independent candidates threw their hats in the ring for three hundred parliamentary seats. Considering BNP and its allies have earlier won with similar vote share and seats, the boycott of 2024 elections by BNP and its allies have significance.

But even before the elections were held the Awami League’s victory and the incumbent Prime Minister’s fourth consecutive term in office became an inevitability after the main opposition, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), decided in December 2023 to boycott the election. It is for these Pranay Sharma, commentator and political affairs commentator foresaw great turmoil ahead for Hasina and questioned whether Hasina would be able to hold Bangladesh together.[49]

Further, based on analysis of past election results, noted South Asia scholar and Bangladesh specialist Partha S. Ghosh pulls no punches in declaring “If the above electoral statistics are analysed, one may surmise that had the elections of 2018 and 2024 been fair the AL might have lost them. If so, it was rather outlandish on the part of Sheikh Hasina to ride roughshod over the opposition and behave autocratically.”[50] Nonetheless, India was the first country to congratulate Hasina on her victory. The US on the other hand which had declared the elections to be neither free nor fair did not impose sanctions and accepted the results though it is believed New Delhi played a conciliatory role.